Juniper (Plain) Titmouse (Baeolophus Ridgwayi)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Merging Science and Management in a Rapidly Changing World: Biodiversity and Management of the Madrean (Q

Preliminary Assessment of Species Richness and Avian Community Dynamics in the Madrean Sky Islands, Arizona Jamie S. Sanderlin, William M. Block, Joseph L. Ganey, and Jose M. Iniguez U.S. Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Flagstaff, Arizona Abstract—The Sky Island mountain ranges of southeastern Arizona contain a unique and rich avifaunal community, including many Neotropical migratory species whose northern breeding range extends to these mountains along with many species typical of similar habitats throughout western North America. Understand- ing ecological factors that influence species richness and biological diversity of both resident and migratory species is important for conservation of this unique bird assemblage. We used a 5-year data set to evaluate avian species distribution across montane habitat types within the Santa Rita, Santa Catalina, Huachuca, Chiricahua, and Pinaleño Mountains. Using point-count data from spring-summer breeding seasons, we de- scribe avian diversity and community dynamics. We use a Bayesian hierarchical model to describe occupancy as a function of vegetative cover type and mountain range latitude, and detection probability as a function of species heterogeneity and sampling effort. By identifying important habitat correlates for avian species, these results can help guide management decisions to minimize loss of key habitats and guide restoration efforts in response to disturbance events in the Madrean Archipelago. Introduction We studied occupancy and cover type associations of forest birds across montane vegetative cover types in the Santa Rita, Santa The Sky Island mountain ranges of southeastern Arizona, USA, Catalina, Huachuca, Chiricahua, and Pinaleño Mountains of south- contain a unique and rich avifaunal community. -

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with Birds Observed Off-Campus During BIOL3400 Field Course

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with birds observed off-campus during BIOL3400 Field course Photo Credit: Talton Cooper Species Descriptions and Photos by students of BIOL3400 Edited by Troy A. Ladine Photo Credit: Kenneth Anding Links to Tables, Figures, and Species accounts for birds observed during May-term course or winter bird counts. Figure 1. Location of Environmental Studies Area Table. 1. Number of species and number of days observing birds during the field course from 2005 to 2016 and annual statistics. Table 2. Compilation of species observed during May 2005 - 2016 on campus and off-campus. Table 3. Number of days, by year, species have been observed on the campus of ETBU. Table 4. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during the off-campus trips. Table 5. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during a winter count of birds on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Table 6. Species observed from 1 September to 1 October 2009 on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Alphabetical Listing of Birds with authors of accounts and photographers . A Acadian Flycatcher B Anhinga B Belted Kingfisher Alder Flycatcher Bald Eagle Travis W. Sammons American Bittern Shane Kelehan Bewick's Wren Lynlea Hansen Rusty Collier Black Phoebe American Coot Leslie Fletcher Black-throated Blue Warbler Jordan Bartlett Jovana Nieto Jacob Stone American Crow Baltimore Oriole Black Vulture Zane Gruznina Pete Fitzsimmons Jeremy Alexander Darius Roberts George Plumlee Blair Brown Rachel Hastie Janae Wineland Brent Lewis American Goldfinch Barn Swallow Keely Schlabs Kathleen Santanello Katy Gifford Black-and-white Warbler Matthew Armendarez Jordan Brewer Sheridan A. -

Backyard Birds, Ornithology Study & ID Guide

See how many of the following common central Florida birds you can find and identify by watching their typical hangouts and habitats, March - October. Record observations in the boxes next to each species. At Birdfeeders (Sunflower seeds are a bird favorite; hummingbird feeders imitate flowers.) Watch for migrants (m) passing through, March to May, September to October; a grosbeak would be a special sighting. Northern Cardinal Tufted Titmouse Blue Jay (Cardinalis cardinalis) (Baeolophus bicolor) (Cyanocitta cristata) Rose-breasted Grosbeak Carolina Chickadee Ruby-throated Humming- (Pheucticus ludovicianus) (m) (Poecile carolinensis) bird (Archilochus colubris) In Trees, on Trunks and Branches (Keep an eye on nearby utility lines and poles too.) Look for mixed flocks moving through the trees hunting insects. Listen for dove coos, owl whoos, woodpecker drums. Mourning Dove Great Crested Northern Parula American Red- (Zenaida macroura) Flycatcher Warbler start Warbler (m) (Myiarchus crinitus) (Setophaga americana) (Setophaga ruticilla) Barred Owl Red-bellied Downy Pileated (Strix varia) Woodpecker Woodpecker Woodpecker (Melanerpes carolinus) (Picoides pubescens) (Dryocopus pileatus) In and Around Bushes, Shrubs, Hedges (Listen for chips, calls, songs in the underbrush.) Brushy vegetation provides nesting sites, food, and cover for many birds. Say Pish-pish-pish-pish—some might peak out! Carolina Wren White-eyed Vireo Common Yellowthroat (Thryothorus ludovicianus) (Vireo griseus) Warbler (Geothlypis trichas) Gray Catbird (m) Brown Thrasher Northern Mockingbird (Dumetella carolinensis) (Toxostoma rufum) (Mimus polyglottos) Large Walking Birds (These species can fly, but spend most of their time foraging on foot.) Sandhill cranes stroll in town & country. Ibis hunt for food on moist ground. Wild turkeys eat mostly plants materials. -

Stories of the Sky Islands: Exhibit Development Resource Guide for Biology and Geology at Chiricahua National Monument and Coronado National Memorial

Stories of the Sky Islands: Exhibit Development Resource Guide for Biology and Geology at Chiricahua National Monument and Coronado National Memorial Prepared for the National Park Service under terms of Cooperative Ecosystems Studies Unit Agreement H1200-05-0003 Task Agreement J8680090020 Prepared by Adam M. Hudson,1 J. Jesse Minor,2,3 Erin E. Posthumus4 In cooperation with the Arizona State Museum The University of Arizona Tucson, AZ Beth Grindell, Principal Investigator May 17, 2013 1: Department of Geosciences, University of Arizona ([email protected]) 2: School of Geography and Development, University of Arizona ([email protected]) 3: Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research, University of Arizona 4: School of Natural Resources and the Environment, University of Arizona ([email protected]) Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................3 Beth Grindell, Ph.D. Ch. 1: Current research and information for exhibit development on the geology of Chiricahua National Monument and Coronado National Memorial, Southeast Arizona, USA..................................................................................................................................... 5 Adam M. Hudson, M.S. Section 1: Geologic Time and the Geologic Time Scale ..................................................5 Section 2: Plate Tectonic Evolution and Geologic History of Southeast Arizona .........11 Section 3: Park-specific Geologic History – Chiricahua -

Deer Creek Mine Closure Water Pipeline Updated Wildlife Resources Report Table of Contents

DEER CREEK MINE CLOSURE WATER PIPELINE UPDATED WILDLIFE RESOURCES REPORT Reviewed by: � Date �� k::V"t-- Dana Truman, Wildlife Biologist; BLM 1 2017 Deer Creek Mine Closure Water Pipeline Updated Wildlife Resources Report Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 PROJECT DESCRIPTION ........................................................................................................... 1 Project Location ........................................................................................................................ 1 Summary of the Proposed Action ............................................................................................ 1 Proposed Project Area/Existing Environment ....................................................................... 2 Description of the Alternatives................................................................................................. 4 EVALUATED SPECIES INFORMATION ................................................................................. 4 Sensitive Plant, Wildlife and Fish Species ............................................................................... 4 Management Indicator Species ................................................................................................ 4 Migratory Birds ......................................................................................................................... 5 ENVIRONMENTAL BASELINE ................................................................................................ -

Historical Biogeography of Tits (Aves: Paridae, Remizidae)

Org Divers Evol (2012) 12:433–444 DOI 10.1007/s13127-012-0101-7 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Historical biogeography of tits (Aves: Paridae, Remizidae) Dieter Thomas Tietze & Udayan Borthakur Received: 29 March 2011 /Accepted: 7 June 2012 /Published online: 14 July 2012 # Gesellschaft für Biologische Systematik 2012 Abstract Tits (Aves: Paroidea) are distributed all over the reconstruction methods produced similar results, but those northern hemisphere and tropical Africa, with highest spe- which consider the likelihood of the transition from one cies numbers in China and the Afrotropic. In order to find area to another should be preferred. out if these areas are also the centers of origin, ancestral areas were reconstructed based on a molecular phylogeny. Keywords Lagrange . S-DIVA . Weighted ancestral area The Bayesian phylogenetic reconstruction was based on analysis . Mesquite ancestral states reconstruction package . sequences for three mitochondrial genes and one nuclear Passeriformes gene. This phylogeny confirmed most of the results of previous studies, but also indicated that the Remizidae are not monophyletic and that, in particular, Cephalopyrus Introduction flammiceps is sister to the Paridae. Four approaches, parsimony- and likelihood-based ones, were applied to How to determine where a given taxon originated has long derive the areas occupied by ancestors of 75 % of the extant been a problem. Darwin (1859) and his followers (e.g., species for which sequence data were available. The Matthew 1915) considered the center of origin to simulta- common ancestor of the Paridae and the Remizidae neously be the diversity hotspot and had the concept of mere inhabited tropical Africa and China. The Paridae, as well dispersal of species out of this area—even if long distances as most of its (sub)genera, originated in China, but had to be covered. -

BAEOLOPHUS ATRICRISTATUS) Christina M

WINTER NOCTURNAL NEST BOX USE OF THE BLACK-CRESTED TITMOUSE (BAEOLOPHUS ATRICRISTATUS) Christina M. Farrell1, M. Clay Green2,3, and Rebekah J. Rylander2 1Selah, Bamberger Ranch Preserve, Johnson City, TX, 78636 USA 2Department of Biology, Texas State University, San Marcos, TX, 78666 USA ABSTRACT.—Nest boxes are used during the breeding season by many cavity-nesting birds; however, less is known about the use of nest boxes as sites for roosting during the winter non- breeding season. The Black-crested Titmouse (Baeolophus atricristatus; hereafter BCTI) is a member of the family Paridae, which is a family containing birds known to utilize nest boxes during the winter seasons. However, the BCTI is a species with undocumented or unknown roosting behavior. For this study, possible factors influencing the propensity for winter roosting in the BCTI were examined. We conducted nocturnal surveys on nest boxes with the use of a wireless infrared cavity inspection camera across two winter field seasons. We analyzed the influence of nightly weather conditions as well as the effect of habitat and vegetation on winter roosting. For the weather variables affecting the probability of roosting, a decrease in temperature was found to increase BCTI roosting. Vegetation density 15 m from nest boxes was also found to influence roosting with an increase in vegetation leading to an increase in roosting frequency. This study has shown nest boxes are of use to BCTI during the non-breeding season and has shed light on some of the factors influencing their winter roosting behavior. Information about the winter ecology of many changes in insulation, body mass, feathers, or lipid avian species is lacking due to a general focus in content help passerines maintain thermoregulation the literature on breeding ecology. -

DRAFT SUPPLEMENTAL SPECIAL-STATUS SPECIES SCREENING ANALYSIS Kirkland High Quality Pozzolan Mining and Reclamation Plan of Operations

DRAFT SUPPLEMENTAL SPECIAL-STATUS SPECIES SCREENING ANALYSIS Kirkland High Quality Pozzolan Mining and Reclamation Plan of Operations Prepared for: U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management, Hassayampa Field Office 21605 North 7th Avenue, Phoenix, Arizona 85027 AZA 37212 May 4, 2018 WestLand Resources, Inc. 4001 E. Paradise Falls Drive Tucson, Arizona 85712 5202069585 Kirkland High Quality Pozzolan Draft Supplemental Special-Status Mining and Reclamation Plan of Operations Species Screening Analysis TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ...................................................................................... 1 2. METHODS ................................................................................................................................................ 1 3. RESULTS ................................................................................................................................................... 3 4. REFERENCES ....................................................................................................................................... 31 TABLES Table 1. Bureau of Land Management Phoenix District Sensitive Species Potential to Occur Screening Analysis Table 2. Arizona Species of Greatest Conservation Need Potential to Occur Screening Analysis Table 3. Migratory Bird Potential to Occur Screening Analysis APPENDICES Appendix A. Bureau of Land Management, Arizona – Bureau Sensitive Species List (February 2017) Appendix B. Arizona Game and Fish Department Environmental -

Tufted Titmouse (Baeolophus Bicolor) Gail A

Tufted Titmouse (Baeolophus bicolor) Gail A. McPeek Kensington, MI 11/29/2008 © Joan Tisdale With a healthy appetite for sunflower seeds, (Click to view a comparison of Atlas I to II) the Tufted Titmouse is a common feeder bird. In fact, many attribute our enthusiasm for Forty years later, Wood (1951) categorized the feeding birds as partly responsible for this Tufted Titmouse as a resident in the species’ noteworthy northward expansion. southernmost two to three tiers of counties, and Titmice can reside year-round in colder climates indicated it was “increasing in numbers and thanks to this convenient chain of fast-food spreading northward.” He noted winter records restaurants. Climate change and reforestation of as far north as Ogemaw and Charlevoix many areas have also played a role in its counties. Zimmerman and Van Tyne (1959) expansion (Grubb and Pravosudov 1994). The reported confirmed breeding records in Tufted Titmouse is found across eastern North Newaygo (1937) and Lapeer (1945) counties, America, west to the Plains and north to plus a family group seen 8 August 1945 in northern New England, southern Ontario, Benzie County. Michigan’s NLP, and central Wisconsin. The southern portion of its range extends across Breeding bird atlases have been timely in Texas and into eastern Mexico. In Texas, the documenting the continuing saga of the Tufted gray-crested form of the East meets with the Titmouse. By the end of MBBA I in 1988, it locally-distributed Black-crested Titmouse. inhabited most (83%) of SLP townships and one-quarter of NLP townships (Eastman 1991). Distribution These records provided a clear picture of this The slow and steady northward expansion of the species’ population increase and major Tufted Titmouse in Michigan is well northward expansion since the 1940s. -

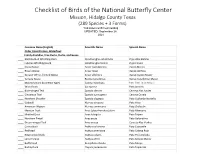

Bird Checklist

Checklist of Birds of the National Butterfly Center Mission, Hidalgo County Texas (289 Species + 3 Forms) *indicates confirmed nesting UPDATED: September 28, 2021 Common Name (English) Scientific Name Spanish Name Order Anseriformes, Waterfowl Family Anatidae, Tree Ducks, Ducks, and Geese Black-bellied Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna autumnalis Pijije Alas Blancas Fulvous Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna bicolor Pijije Canelo Snow Goose Anser caerulescens Ganso Blanco Ross's Goose Anser rossii Ganso de Ross Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons Ganso Careto Mayor Canada Goose Branta canadensis Ganso Canadiense Mayor Muscovy Duck (Domestic type) Cairina moschata Pato Real (doméstico) Wood Duck Aix sponsa Pato Arcoíris Blue-winged Teal Spatula discors Cerceta Alas Azules Cinnamon Teal Spatula cyanoptera Cerceta Canela Northern Shoveler Spatula clypeata Pato Cucharón Norteño Gadwall Mareca strepera Pato Friso American Wigeon Mareca americana Pato Chalcuán Mexican Duck Anas (platyrhynchos) diazi Pato Mexicano Mottled Duck Anas fulvigula Pato Tejano Northern Pintail Anas acuta Pato Golondrino Green-winged Teal Anas crecca Cerceta Alas Verdes Canvasback Aythya valisineria Pato Coacoxtle Redhead Aythya americana Pato Cabeza Roja Ring-necked Duck Aythya collaris Pato Pico Anillado Lesser Scaup Aythya affinis Pato Boludo Menor Bufflehead Bucephala albeola Pato Monja Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis Pato Tepalcate Order Galliformes, Upland Game Birds Family Cracidae, Guans and Chachalacas Plain Chachalaca Ortalis vetula Chachalaca Norteña Family Odontophoridae, -

Natural Resource Condition Assessment Horseshoe Bend National Military Park

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Natural Resource Condition Assessment Horseshoe Bend National Military Park Natural Resource Report NPS/SECN/NRR—2015/981 ON THE COVER Photo of the Tallapoosa River, viewed from Horseshoe Bend National Military Park Photo Courtesy of Elle Allen Natural Resource Condition Assessment Horseshoe Bend National Military Park Natural Resource Report NPS/SECN/NRR—2015/981 JoAnn M. Burkholder, Elle H. Allen, Stacie Flood, and Carol A. Kinder Center for Applied Aquatic Ecology North Carolina State University 620 Hutton Street, Suite 104 Raleigh, NC 27606 June 2015 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. The series supports the advancement of science, informed decision-making, and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series also provides a forum for presenting more lengthy results that may not be accepted by publications with page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

Thousand Oaks Groundwater Utilization Project

2775 North Ventura Road, Suite 100 Oxnard, California 93036 805-973-5700 FAX: 805-973-1440 Thousand Oaks Groundwater Utilization Project Public Draft CEQA Initial Study/Mitigated Negative Declaration August 2020 Prepared for City of Thousand Oaks 2100 Thousand Oaks Blvd. Thousand Oaks, CA 91362 K/J Project No. 1744405*02 Table of Contents List of Tables ................................................................................................................................ iv List of Figures................................................................................................................................ v List of Appendices ......................................................................................................................... v List of Acronyms ............................................................................................................................ v Section 1: Mitigated Negative Declaration ................................................ 1-1 1.1 Organization of this IS/MND ................................................................ 1-5 Section 2: Project Description .................................................................... 2-1 2.1 Overview of the Proposed Project ....................................................... 2-1 2.2 City of Thousand Oaks ........................................................................ 2-2 2.3 Project Goals and Objectives .............................................................. 2-2 2.4 Project Location .................................................................................