BAEOLOPHUS ATRICRISTATUS) Christina M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with Birds Observed Off-Campus During BIOL3400 Field Course

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with birds observed off-campus during BIOL3400 Field course Photo Credit: Talton Cooper Species Descriptions and Photos by students of BIOL3400 Edited by Troy A. Ladine Photo Credit: Kenneth Anding Links to Tables, Figures, and Species accounts for birds observed during May-term course or winter bird counts. Figure 1. Location of Environmental Studies Area Table. 1. Number of species and number of days observing birds during the field course from 2005 to 2016 and annual statistics. Table 2. Compilation of species observed during May 2005 - 2016 on campus and off-campus. Table 3. Number of days, by year, species have been observed on the campus of ETBU. Table 4. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during the off-campus trips. Table 5. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during a winter count of birds on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Table 6. Species observed from 1 September to 1 October 2009 on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Alphabetical Listing of Birds with authors of accounts and photographers . A Acadian Flycatcher B Anhinga B Belted Kingfisher Alder Flycatcher Bald Eagle Travis W. Sammons American Bittern Shane Kelehan Bewick's Wren Lynlea Hansen Rusty Collier Black Phoebe American Coot Leslie Fletcher Black-throated Blue Warbler Jordan Bartlett Jovana Nieto Jacob Stone American Crow Baltimore Oriole Black Vulture Zane Gruznina Pete Fitzsimmons Jeremy Alexander Darius Roberts George Plumlee Blair Brown Rachel Hastie Janae Wineland Brent Lewis American Goldfinch Barn Swallow Keely Schlabs Kathleen Santanello Katy Gifford Black-and-white Warbler Matthew Armendarez Jordan Brewer Sheridan A. -

Backyard Birds, Ornithology Study & ID Guide

See how many of the following common central Florida birds you can find and identify by watching their typical hangouts and habitats, March - October. Record observations in the boxes next to each species. At Birdfeeders (Sunflower seeds are a bird favorite; hummingbird feeders imitate flowers.) Watch for migrants (m) passing through, March to May, September to October; a grosbeak would be a special sighting. Northern Cardinal Tufted Titmouse Blue Jay (Cardinalis cardinalis) (Baeolophus bicolor) (Cyanocitta cristata) Rose-breasted Grosbeak Carolina Chickadee Ruby-throated Humming- (Pheucticus ludovicianus) (m) (Poecile carolinensis) bird (Archilochus colubris) In Trees, on Trunks and Branches (Keep an eye on nearby utility lines and poles too.) Look for mixed flocks moving through the trees hunting insects. Listen for dove coos, owl whoos, woodpecker drums. Mourning Dove Great Crested Northern Parula American Red- (Zenaida macroura) Flycatcher Warbler start Warbler (m) (Myiarchus crinitus) (Setophaga americana) (Setophaga ruticilla) Barred Owl Red-bellied Downy Pileated (Strix varia) Woodpecker Woodpecker Woodpecker (Melanerpes carolinus) (Picoides pubescens) (Dryocopus pileatus) In and Around Bushes, Shrubs, Hedges (Listen for chips, calls, songs in the underbrush.) Brushy vegetation provides nesting sites, food, and cover for many birds. Say Pish-pish-pish-pish—some might peak out! Carolina Wren White-eyed Vireo Common Yellowthroat (Thryothorus ludovicianus) (Vireo griseus) Warbler (Geothlypis trichas) Gray Catbird (m) Brown Thrasher Northern Mockingbird (Dumetella carolinensis) (Toxostoma rufum) (Mimus polyglottos) Large Walking Birds (These species can fly, but spend most of their time foraging on foot.) Sandhill cranes stroll in town & country. Ibis hunt for food on moist ground. Wild turkeys eat mostly plants materials. -

Historical Biogeography of Tits (Aves: Paridae, Remizidae)

Org Divers Evol (2012) 12:433–444 DOI 10.1007/s13127-012-0101-7 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Historical biogeography of tits (Aves: Paridae, Remizidae) Dieter Thomas Tietze & Udayan Borthakur Received: 29 March 2011 /Accepted: 7 June 2012 /Published online: 14 July 2012 # Gesellschaft für Biologische Systematik 2012 Abstract Tits (Aves: Paroidea) are distributed all over the reconstruction methods produced similar results, but those northern hemisphere and tropical Africa, with highest spe- which consider the likelihood of the transition from one cies numbers in China and the Afrotropic. In order to find area to another should be preferred. out if these areas are also the centers of origin, ancestral areas were reconstructed based on a molecular phylogeny. Keywords Lagrange . S-DIVA . Weighted ancestral area The Bayesian phylogenetic reconstruction was based on analysis . Mesquite ancestral states reconstruction package . sequences for three mitochondrial genes and one nuclear Passeriformes gene. This phylogeny confirmed most of the results of previous studies, but also indicated that the Remizidae are not monophyletic and that, in particular, Cephalopyrus Introduction flammiceps is sister to the Paridae. Four approaches, parsimony- and likelihood-based ones, were applied to How to determine where a given taxon originated has long derive the areas occupied by ancestors of 75 % of the extant been a problem. Darwin (1859) and his followers (e.g., species for which sequence data were available. The Matthew 1915) considered the center of origin to simulta- common ancestor of the Paridae and the Remizidae neously be the diversity hotspot and had the concept of mere inhabited tropical Africa and China. The Paridae, as well dispersal of species out of this area—even if long distances as most of its (sub)genera, originated in China, but had to be covered. -

Tufted Titmouse (Baeolophus Bicolor) Gail A

Tufted Titmouse (Baeolophus bicolor) Gail A. McPeek Kensington, MI 11/29/2008 © Joan Tisdale With a healthy appetite for sunflower seeds, (Click to view a comparison of Atlas I to II) the Tufted Titmouse is a common feeder bird. In fact, many attribute our enthusiasm for Forty years later, Wood (1951) categorized the feeding birds as partly responsible for this Tufted Titmouse as a resident in the species’ noteworthy northward expansion. southernmost two to three tiers of counties, and Titmice can reside year-round in colder climates indicated it was “increasing in numbers and thanks to this convenient chain of fast-food spreading northward.” He noted winter records restaurants. Climate change and reforestation of as far north as Ogemaw and Charlevoix many areas have also played a role in its counties. Zimmerman and Van Tyne (1959) expansion (Grubb and Pravosudov 1994). The reported confirmed breeding records in Tufted Titmouse is found across eastern North Newaygo (1937) and Lapeer (1945) counties, America, west to the Plains and north to plus a family group seen 8 August 1945 in northern New England, southern Ontario, Benzie County. Michigan’s NLP, and central Wisconsin. The southern portion of its range extends across Breeding bird atlases have been timely in Texas and into eastern Mexico. In Texas, the documenting the continuing saga of the Tufted gray-crested form of the East meets with the Titmouse. By the end of MBBA I in 1988, it locally-distributed Black-crested Titmouse. inhabited most (83%) of SLP townships and one-quarter of NLP townships (Eastman 1991). Distribution These records provided a clear picture of this The slow and steady northward expansion of the species’ population increase and major Tufted Titmouse in Michigan is well northward expansion since the 1940s. -

Bird Checklist

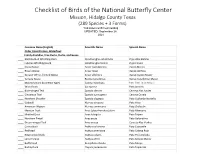

Checklist of Birds of the National Butterfly Center Mission, Hidalgo County Texas (289 Species + 3 Forms) *indicates confirmed nesting UPDATED: September 28, 2021 Common Name (English) Scientific Name Spanish Name Order Anseriformes, Waterfowl Family Anatidae, Tree Ducks, Ducks, and Geese Black-bellied Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna autumnalis Pijije Alas Blancas Fulvous Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna bicolor Pijije Canelo Snow Goose Anser caerulescens Ganso Blanco Ross's Goose Anser rossii Ganso de Ross Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons Ganso Careto Mayor Canada Goose Branta canadensis Ganso Canadiense Mayor Muscovy Duck (Domestic type) Cairina moschata Pato Real (doméstico) Wood Duck Aix sponsa Pato Arcoíris Blue-winged Teal Spatula discors Cerceta Alas Azules Cinnamon Teal Spatula cyanoptera Cerceta Canela Northern Shoveler Spatula clypeata Pato Cucharón Norteño Gadwall Mareca strepera Pato Friso American Wigeon Mareca americana Pato Chalcuán Mexican Duck Anas (platyrhynchos) diazi Pato Mexicano Mottled Duck Anas fulvigula Pato Tejano Northern Pintail Anas acuta Pato Golondrino Green-winged Teal Anas crecca Cerceta Alas Verdes Canvasback Aythya valisineria Pato Coacoxtle Redhead Aythya americana Pato Cabeza Roja Ring-necked Duck Aythya collaris Pato Pico Anillado Lesser Scaup Aythya affinis Pato Boludo Menor Bufflehead Bucephala albeola Pato Monja Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis Pato Tepalcate Order Galliformes, Upland Game Birds Family Cracidae, Guans and Chachalacas Plain Chachalaca Ortalis vetula Chachalaca Norteña Family Odontophoridae, -

Natural Resource Condition Assessment Horseshoe Bend National Military Park

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Natural Resource Condition Assessment Horseshoe Bend National Military Park Natural Resource Report NPS/SECN/NRR—2015/981 ON THE COVER Photo of the Tallapoosa River, viewed from Horseshoe Bend National Military Park Photo Courtesy of Elle Allen Natural Resource Condition Assessment Horseshoe Bend National Military Park Natural Resource Report NPS/SECN/NRR—2015/981 JoAnn M. Burkholder, Elle H. Allen, Stacie Flood, and Carol A. Kinder Center for Applied Aquatic Ecology North Carolina State University 620 Hutton Street, Suite 104 Raleigh, NC 27606 June 2015 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. The series supports the advancement of science, informed decision-making, and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series also provides a forum for presenting more lengthy results that may not be accepted by publications with page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

2020 National Bird List

2020 NATIONAL BIRD LIST See General Rules, Eye Protection & other Policies on www.soinc.org as they apply to every event. Kingdom – ANIMALIA Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias ORDER: Charadriiformes Phylum – CHORDATA Snowy Egret Egretta thula Lapwings and Plovers (Charadriidae) Green Heron American Golden-Plover Subphylum – VERTEBRATA Black-crowned Night-heron Killdeer Charadrius vociferus Class - AVES Ibises and Spoonbills Oystercatchers (Haematopodidae) Family Group (Family Name) (Threskiornithidae) American Oystercatcher Common Name [Scientifc name Roseate Spoonbill Platalea ajaja Stilts and Avocets (Recurvirostridae) is in italics] Black-necked Stilt ORDER: Anseriformes ORDER: Suliformes American Avocet Recurvirostra Ducks, Geese, and Swans (Anatidae) Cormorants (Phalacrocoracidae) americana Black-bellied Whistling-duck Double-crested Cormorant Sandpipers, Phalaropes, and Allies Snow Goose Phalacrocorax auritus (Scolopacidae) Canada Goose Branta canadensis Darters (Anhingidae) Spotted Sandpiper Trumpeter Swan Anhinga Anhinga anhinga Ruddy Turnstone Wood Duck Aix sponsa Frigatebirds (Fregatidae) Dunlin Calidris alpina Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Magnifcent Frigatebird Wilson’s Snipe Northern Shoveler American Woodcock Scolopax minor Green-winged Teal ORDER: Ciconiiformes Gulls, Terns, and Skimmers (Laridae) Canvasback Deep-water Waders (Ciconiidae) Laughing Gull Hooded Merganser Wood Stork Ring-billed Gull Herring Gull Larus argentatus ORDER: Galliformes ORDER: Falconiformes Least Tern Sternula antillarum Partridges, Grouse, Turkeys, and -

Tufted and Black-Crested—Both Species of Titmouse Favor Texas

Texas Bluebird Society Newsletter ▪ Volume 12. Issue 2 MAY 2013 Other Cavity-Nesters: Tufted and Black-Crested—Both Species of Titmouse Favor Texas By Helen Munro, New Texas Bluebird Society member. Past President and Editor of the North Carolina Bluebird Society The Eastern Bluebird is the “poster child” for the secondary cavity nesters. Secondary cavity nesters are the birds that cannot make their own cavities in trees and rely on the work of woodpeckers, rotten limbs falling out leaving knotholes, newspaper tubes, mail- boxes, and, of course, nestboxes supplied by thousands of individ- uals, member and non-members of bluebird societies, throughout the North American continent. This activity has moved the blue- birds to a secure place in our environment. The bluebird recovery has been so successful that people doing research on the Brown-headed Nuthatch, another secondary cavity nester, have asked bluebird enthusiasts in and near pine forests to reduce the hole size in the standard nestboxes from one and a half inch to one inch. By attaching a washer with a one inch opening, the Brown-headed Nuthatch uses the early nesting period, and removal of the washer invites the bluebirds to take the second nesting cycle. However, the star of this article is the Tufted Titmouse (Baeolophus Black-Crested Titmouse (above photos) is only found in bicolor). Its grey crest, placed like a jaunty hat on its head, makes it Texas and Mexico. Tufted Titmouse lives here year-round. easy to pick out of a crowd. Its five and a half inch body is slightly larger than the four and half inch Carolina Chickadee and the three and half inch Brown-headed Nuthatch. -

Final Format

Forest Disturbance Effects on Insect and Bird Communities: Insectivorous Birds in Coast Live Oak Woodlands and Leaf Litter Arthropods in the Sierra Nevada by Kyle Owen Apigian B.A. (Bowdoin College) 1998 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science, Policy, and Management in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in Charge: Professor Barbara Allen-Diaz, Chair Assistant Professor Scott Stephens Professor Wayne Sousa Spring 2005 The dissertation of Kyle Owen Apigian is approved: Chair Date Date Date University of California, Berkeley Spring 2005 Forest Disturbance Effects on Insect and Bird Communities: Insectivorous Birds in Coast Live Oak Woodlands and Leaf Litter Arthropods in the Sierra Nevada © 2005 by Kyle Owen Apigian TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Figures ii List of Tables iii Preface iv Acknowledgements Chapter 1: Foliar arthropod abundance in coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia) 1 woodlands: effects of tree species, seasonality, and “sudden oak death”. Chapter 2: Insectivorous birds change their foraging behavior in oak woodlands affected by Phytophthora ramorum (“sudden oak death”). Chapter 3: Cavity nesting birds in coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia) woodlands impacted by Phytophthora ramorum: use of artificial nest boxes and arthropod delivery to nestlings. Chapter 4: Biodiversity of Coleoptera and other leaf litter arthropods and the importance of habitat structural features in a Sierra Nevada mixed-conifer forest. Chapter 5: Fire and fire surrogate treatment effects on leaf litter arthropods in a western Sierra Nevada mixed-conifer forest. Conclusions References Appendices LIST OF FIGURES Page Chapter 1 Figure 1. -

Juniper (Plain) Titmouse (Baeolophus Ridgwayi)

June 2007 Juniper (Plain) Titmouse (Baeolophus ridgwayi) INDICATOR SPECIES HABITAT The plain titmouse is an indicator species for piñon-juniper (PJ) canopies (USDA 1986a, p. 97). Until 1997 the taxa was regarded as a single species (Parus inornatus). The taxa were split into two separate species; oak titmouse (Baeolophus inornatus) and juniper titmouse (Baeolophus ridgwayi). The oak titmouse is found in the oak woodlands of the Pacific and is not found in New Mexico (Cicero 2000). The juniper titmouse inhabits juniper and piñon-juniper woodlands of the intermountain region (id.). Further discussion in this document will call the species juniper titmouse, however, it is the same species identified as an indicator species in 1986 (USDA 1986a, p. 97). The juniper titmouse is a resident of deciduous or mixed woodlands, favoring oak and piñon- juniper (Ehrlich et al. 1988). The titmouse usually nests in natural cavities or old woodpecker holes primarily in oak trees, but it is capable of excavating its own cavity in rotted wood. The species feeds mainly on large seeds from piñon pine and juniper, as well as, acorns (Christman 2001), insects, and occasional fruits, and is also a bark gleaner (Cicero 2000; Scott et al. 1977; Scott and Patton 1989). As a cavity nester, large, older senescent trees are an important habitat feature (Pavlacky and Anderson 2001). Potential Habitat Distribution Based on the 2003 GIS vegetation cover data, the Carson National Forest currently supports approximately 355,409 acres of piñon-juniper habitat (USDA 2003a). As displayed on Map 1, potential habitat for the juniper titmouse on the Carson National Forest is abundant and well distributed across the Forest. -

A Practical Checklist of the Birds of New York

A Practical Checklist of the Birds of New York By David Lahti (with help from Seth Wollney and César Castillo) 1/2016 20 orders, 56 families, 309 species Ornithology 2016 Class Checklist, May 19 (FINAL) 14 orders, 40 families, 123 species Order ANSERIFORMES – waterfowl (1 family, 37 species) Family Anatidae: Geese, swans, and ducks (37 species) Greater white-fronted goose, Anser albifrons Snow goose, Chen caerulescens Ross's goose, Chen rossii Brant, Branta bernicla Cackling goose, Branta hutchinsii Canada goose, Branta canadensis *Mute swan, Cygnus olor Tundra swan, Cygnus columbianus Wood duck, Aix sponsa Gadwall, Anas strepera Eurasian wigeon, Anas penelope American wigeon, Anas americana American black duck, Anas rubripes Mallard, Anas platyrhynchos Blue-winged teal, Anas discors Northern shoveler, Anas clypeata Northern pintail, Anas acuta Green-winged teal, Anas crecca Canvasback, Aythya valisineria Redhead, Aythya americana Ring-necked duck, Aythya collaris Greater scaup, Aythya marila Lesser scaup, Aythya affinis King eider, Somateria spectabilis Common eider, Somateria mollissima Harlequin duck, Histrionicus histrionicus Surf scoter, Melanitta perspicillata White-winged scoter, Melanitta fusca Black scoter, Melanitta americana (near-threatened) Long-tailed duck, Clangula hyemalis (vulnerable) Bufflehead, Bucephala albeola Common goldeneye, Bucephala clangula Barrow's goldeneye, Bucephala islandica Hooded merganser, Lophodytes cucullatus Common merganser, Mergus merganser Red-breasted merganser, Mergus serrator Ruddy duck, Oxyura -

Joseph Grinnell: 1877-1939 (With Frontispiece and Eleven Other Ills.)

,~ ““,Y.,.,,‘ THE CONDOR VOLUME XL11 JANUARY-FEBRUARY, 1940 NUMBER 1 JOSEPH GRINNELL: 1877- 1939 WITH FRONTISPIECE AND ELEVEN OTHER ILLUSTRATIONS By HILDA WOOD GRINNELL Joseph Grinnell was born on February 2 7, 1877, at the Kiowa, Comanche, and Wichita Indian Agency on the Washita River, forty miles from old Fort Sill, Indian Territory, son of the agency physician. His father was Fordyce Grinnell, M.D., a birthright member of the Society of Friends and second son of Jeremiah Austin Grinnell, minister of note among the Friends of Vermont and Iowa, and later of California. As were his distant cousins, George Bird Grinnell, and Joseph Grinnell of New Bedford, Fordyce Grinnell was descended from Matthew Grenelle, a French Huguenot who was admitted as an inhabitant of Newport, Rhode Island, May 20, 1638. His mother was Sarah Elizabeth Pratt, also a birthright Quaker, whose father, too, was a minister, Joseph Howland Pratt of Maine and New Hampshire. Both of Joseph Grinnell’s parents were descendedfrom “early-come-avers.” Frances Cooke, John Alden, and Richard Warren of the Mayflower, Henry Howland, who followed his brother John to the new land, Thomas Taber, and the Worths of Nantucket were among their progeni- tors. New England traits of character were Joseph Grinnell’s heritage. Fordyce Grinnell as a young physician soon left the Indian service for two years of private practice in Marysville, Tennessee, but he was restless for the prairies. 1880 found him again in the service, this time in the Dakotas, where Chief Red Cloud’s people were gathered. Here the family circle was completed by the birth of a second son, For- dyce, Jr., at Pine Ridge Agency, and a daughter, Elizabeth, at Rosebud.