SE Asia Volume 1Rev.Pdf (8.403Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Silent Homage to Amaterasu: Kagura Secret Songs at Ise Jingū and the Imperial Palace Shrine

In Silent Homage to Amaterasu: Kagura Secret Songs at Ise Jingū and the Imperial Palace Shrine in Modern and Pre-modern Japan Michiko Urita A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2017 Reading Committee: Patricia Shehan Campbell, Chair Jeffrey M. Perl Christina Sunardi Paul S. Atkins Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music ii ©Copyright 2017 Michiko Urita iii University of Washington Abstract In Silent Homage to Amaterasu: Kagura Secret Songs at Ise Jingū and the Imperial Palace Shrine in Modern and Pre-modern Japan Michiko Urita Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Patricia Shehan Campbell Music This dissertation explores the essence and resilience of the most sacred and secret ritual music of the Japanese imperial court—kagura taikyoku and kagura hikyoku—by examining ways in which these two songs have survived since their formation in the twelfth century. Kagura taikyoku and kagura hikyoku together are the jewel of Shinto ceremonial vocal music of gagaku, the imperial court music and dances. Kagura secret songs are the emperor’s foremost prayer offering to the imperial ancestral deity, Amaterasu, and other Shinto deities for the well-being of the people and Japan. I aim to provide an understanding of reasons for the continued and uninterrupted performance of kagura secret songs, despite two major crises within Japan’s history. While foreign origin style of gagaku was interrupted during the Warring States period (1467-1615), the performance and transmission of kagura secret songs were protected and sustained. In the face of the second crisis during the Meiji period (1868-1912), which was marked by a threat of foreign invasion and the re-organization of governance, most secret repertoire of gagaku lost their secrecy or were threatened by changes to their traditional system of transmissions, but kagura secret songs survived and were sustained without losing their iv secrecy, sacredness, and silent performance. -

“PRESENCE” of JAPAN in KOREA's POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Ju

TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Jung M.A. in Ethnomusicology, Arizona State University, 2001 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2007 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Eun-Young Jung It was defended on April 30, 2007 and approved by Richard Smethurst, Professor, Department of History Mathew Rosenblum, Professor, Department of Music Andrew Weintraub, Associate Professor, Department of Music Dissertation Advisor: Bell Yung, Professor, Department of Music ii Copyright © by Eun-Young Jung 2007 iii TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE Eun-Young Jung, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Korea’s nationalistic antagonism towards Japan and “things Japanese” has mostly been a response to the colonial annexation by Japan (1910-1945). Despite their close economic relationship since 1965, their conflicting historic and political relationships and deep-seated prejudice against each other have continued. The Korean government’s official ban on the direct import of Japanese cultural products existed until 1997, but various kinds of Japanese cultural products, including popular music, found their way into Korea through various legal and illegal routes and influenced contemporary Korean popular culture. Since 1998, under Korea’s Open- Door Policy, legally available Japanese popular cultural products became widely consumed, especially among young Koreans fascinated by Japan’s quintessentially postmodern popular culture, despite lingering resentments towards Japan. -

Freebern, Charles L., 1934

THE MUSIC OF INDIA, CHINA, JAPAN AND OCEANIA: A SOURCE BOOK FOR TEACHERS Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Freebern, Charles L., 1934- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 06:04:40 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/290233 This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 70-6670 FREEBERN, Charles L., 1934- IHE MUSIC OF INDIA, CHINA/JAPAN AND OCEANIA: A SOURCE BOOK FOR TEACHERS. [Appendix "Pronounciation Tape Recording" available for consultation at University of Arizona Library]. University of Arizona, A. Mus.D., 1969 Music University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan CHARLES L. FREEBERN 1970 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED • a • 111 THE MUSIC OP INDIA, CHINA, JAPAN AND OCEANIA: A SOURCE BOOK FOR TEACHERS by Charles L. Freebern A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 6 9 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA. GRADUATE COLLEGE I hereby recommend that this dissertation prepared under my direction by Charles L, Freebern entitled THE MUSIC OF INDIA, CHINA, JAPAN AND OCEANIA: A SOURCE BOOK FOR TEACHERS be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement of the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts &• 7?)• as. in? Dissertation Director fca^e After inspection of the final copy of the dissertation, the following members of the Final Examination Connnittee concur in its approval and recommend its acceptance:" _ ^O^tLUA ^ AtrK. -

This Was Drawn from the Complete Dump of the Japanese Wikipedia On

1. of 60. Call 2. To 61. Then 3. Make 62. Meeting 4. The 63. It 5. The 64. Machine 6. But 65. meet 7. When 66. receive 8. year 67. Many 9. so 68. player 10. I 69. Case 11. Month 70. Against 12. Also 71. However 13. From 72. Take 14. Day 73. Showa 15. Become 74. the work 16. Thing 75. Earth 17. Have 76. Medium 18. Twist 77. use 19. Ya 78. both 20. Such as 79. school 21. say 80. word 22. Japan 81. he 23. Because 82. go 24. This 83. America 25. Man 84. at that time 26. That 85. program 27. Until 86. car 28. Thing 87. Shrine 29. What 88. river 30. or 89. Movie 31. This 90. Place 32. Do 91. to see 33. Yo 92. tv set 34. Be able to 93. system 35. station 94. the study 36. country 95. town 37. From 96. east 38. University 97. Presence 39. the current 98. Activity 40. rear 99. Sale 41. Or 100. other 42. line 101. Graduate 43. Unexpected 102. Age 44. broadcast 103. the company 45. issue 104. Authority 46. Army 105. development of 47. No 106. Minute 48. Section 107. West 49. Possess 108. Railroad 50. Place 109. Law 51. given name 110. Office 52. Time 111. Furthermore 53. world 112. only 54. Time 113. Between 55. War 114. mountain 56. Era 115. formula 57. Tokyo 116. island 58. Place 117. It should be noted 59. But 118. Possible 119. Germany 178. Meiji 120. representative 179. Living 121. -

The Musical and Spiritual Duality of Nomai Music in Northern Japan

The Musical and Spiritual Duality of Nomai Music in Northern Japan Susan Asai Northeastern University N omai is a dance drama that was introduced, almost four-hundred years ago, to the district of Higashidorimura - an area located at the northernmost tip of the main island of Honshu. Itinerant priests known as yamabushi, or mountain priests, developed nomai as a vehicle for evangelizing to provincial audiences. They eventually taught the tradition to the local population to insure its survival, and today it continues to be performed by fourteen villages. Yamabushi were practitioners of Shugendo, an ascetic religion which combined primordial beliefs in the sacredness of mountains with the precepts and rituals of Shintoism, Shingon Buddhism, Confucianism, and religious Taoism. They synthesized Buddhist musical elements and Shugendo beliefs with already existing folk Shinto performing traditions associated with agricultural rites and the appeasement of deities; this synthesis gives l10mai its unique character. The present study centers on the ceremonial and prayer pieces which form the core of the l10mai repertoire and represent the ritual essence of the tradition. A look at Japan's two major religions provides a background for investigating nomai's duality. Shinto, translated as 'The Way of the Gods,' is the indigenous religion of Japan that combines the veneration of ancestors and nature worship. It originated from shamanic rituals and beliefs dating back to Japan's antiquity and served as the state religion during the Yamato period from the 3rd to the 6th century. Shinto music and dance known as kagura, meaning" entertainment for the gods," serves as a way to purify the worship place and to conjure and entertain deities as a form of prayer to prolong life. -

1986 Festival of American Folklife Smithsonian Institution National Park Service Hanadaue Periotmance Ot Rice Planting in the Village Ol Mibu, Hiroshima Prefecture

1986 Festival of American Folklife Smithsonian Institution National Park Service Hanadaue periotmance ot rice planting in the village ol Mibu, Hiroshima Prefecture. PHOTO BY ISAO SUTOU Split-oak b.Lsl<ct.s b\ Maggie Mtiriihy. Cannon County Tennessee PHOTO BY ROBY COGSWELL, COURTESY TENNESSEE ARTS COMMISSION * « . <% "te^ V w l» 4. "- ^^ 1^ # /^ '^18i^ '^ 4^ € ^ m «^ ^ tk^ \ ' 4 '. \ 1 4 r ^ ^ ^* # ». 4 M^ J* * > <ih*^ r «- % ^^^ w ^'<i{> S I jR "^^ iM « 5r 1986 Festival of American Folklife Smithsonian Institution National Park Service June 25-29/July 2-6 Contents 4 The Twentieth Festival by Robert McC. Adams, Secretary, Smithsonian Institution 6 Pride in America's Cultural Diversity by William Penn Mott, Jr., Director, National Park Service 7 The Midway on the Mall Twenty Years ofthe Festival ofAmerican Folklife by Robert Cantwell 1 2 Trial Laivyers as Storytellers by Samuel Schrager 17 Japanese Village Farm Life by Kozo Yamaji 22 Rice Cultivation inJapan andTa-hayashi Festhal ofAmerican Folklilf Program B(x)k by Frank Hoff Smithsonian Institution 1986 Editor: Thomas Vennum, Jr. 26 Shigaraki Pottery by Louise Allison Co rt Designer: Daphne ShuttJewortli 32 Diverse Influences in the Development aJapanese Folk Drama Assistant Designer Joan Wolbier of Coordinator: Arlene Liebenau by Susan Asai Typesetter: Harlowe Typography 36 Traditional Folk Song in ModemJapan Printer: Ajneriprint Inc. by David Hughes Typeface: ITC Garamond Paper: 80 lb. Patina cover and text 41 Tennessee Folklife: Three Rooms Under One Roof Flysheet Kinwashi cream or Chiri new- by Robert Cogswell er Chiri Ranzan or Kaji natural Insert: 70 11). adobe tan text 46 Country Music in Tennessee: From Hollow to Honky Tonk byJoseph T. -

Tsugaru Shamisen and Modern Japanese Identity

TSUGARU SHAMISEN AND MODERN JAPANESE IDENTITY GERALD T. McGOLDRICK A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN MUSIC YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO MARCH 2017 © Gerry McGoldrick, 2017 ABSTRACT The shamisen, a Japanese plucked lute dating back to the seventeenth century, began to be played by blind itinerant male performers known as bosama in the late nineteenth century in the Tsugaru region, part of present-day Aomori prefecture in northern Japan. By the early twentieth century it was used by sighted players to accompany local folk songs, and from the 1940s entirely instrumental versions of a few of the folk songs were being performed. In the late 1950s the term Tsugaru shamisen was coined and the genre began to get national attention. This culminated in a revival in the 1970s centred on Takahashi Chikuzan, who had made a living as a bosama in the prewar period. In the wake of the 70s boom a contest began to be held annually in Hirosaki, the cultural capital of the Tsugaru region. This contest nurtured a new generation of young players from all over Japan, eventually spawning other national contests in every corner of the country. Chikuzan’s death in 1998 was widely reported in the media, and Yoshida Ryōichirō and Yoshida Kenichi, brothers who had stood out at the contests, were cast as the new face of Tsugaru shamisen. From about 2000 a new Tsugaru shamisen revival was under way, and the music could be heard as background music on Television programs and commercials representing a modern Japan that had not lost its traditions. -

Meiji Jingu-About Meiji Jingu

Meiji Jingu-About Meiji Jingu- (Photo: Meiji Jingu Naien) Welcome to Meiji Jingu! Meiji Jingu is a Shinto shrine. Shinto is called Japan's ancient original religion, and it is deeply rooted in the way of Japanese life. Shinto has no founder, no holy book, and not even the concept of religious conversion, but Shinto values for example harmony with nature and virtues such as "Magokoro (sincere heart)". In Shinto, some divinity is found as Kami (divine spirit), or it may be said that there is an unlimited number of Kami. You can see Kami in mythology, in nature, and in human beings. From ancient times, Japanese people have felt awe and gratitude towards such Kami and dedicated shrines to many of them. This shrine is dedicated to the divine souls of Emperor Meiji and his consort Empress Shoken (their tombs are in Kyoto). Emperor Meiji passed away in 1912 and Empress Shoken in 1914. After their demise, people wished to commemorate their virtues and to venerate them forever. So they donated 100,000 trees from all over Japan and from overseas, and they worked voluntarily to create this forest. Thus, thanks to the sincere heart of the people, this shrine was established on November 1, 1920. Facts about Meiji Jingu: Enshrined deities: souls of Emperor Meiji and Empress Shoken Foundation: November 1, 1920 Area: 700,000 m2 (inner precinct) http://www.meijijingu.or.jp/english/about/1.html [6/19/2014 8:39:40 PM] Meiji Jingu-About Meiji Jingu- The main shrine buildings In 1945, the original shrine buildings (except for Shukueisha and Minami-Shinmon) were burnt down in the air raids of the war. -

Glossary of Selected Terms 365

2240_GST.qxd 11/26/07 8:47 PM Page 364 G LOSSARY O F S ELECTED T ERMS Brief definitions are given for a selection of Japanese words that occur within the text. Many of these only occur once and thus are unlikely to need looking up, but they are included here so that a read-through of the Glossary might evoke a sense of the vocabulary of the min’yo- world. Many also occur in the General Index under appropriate headings. Sino-Japanese characters are included in a few cases to pre- vent ambiguity. aji: ‘flavour’, an essential but bushi: common suffix in folk song undefinable element in good min’yo- titles; derived from fushi ‘melody’ performance buyo--kayo-: dances to accompany ameuri: sweets vendors enka; also called kayo--buyo- angura: ‘underground’ folk group chiho--riyo-: a 1930s designation for anko-iri: ‘filled with sweet bean- folk song paste’; a type of sweet bread cho-: ‘town’; also pronounced machi atouta: ‘aftersong’ cho-nin: ‘townspeople’, often implying bareuta: ‘bawdy songs’ especially merchants bin-zasara: a set of concussion daikoku-mai: dance of the god plaques used for percussion Daikoku, performed door-to-door at biwa: pear-shaped lute usually used to New Year’s accompany sung ballads danmono: (among other meanings) long bon-odori: dances of the Bon festival ballads in the repertoire of the goze bosama: ‘priest’, but also a common densho-: (oral) transmission, tradition traditional term for a blind male dento-: tradition musician dodoitsu: a traditional popular song bunka: ‘culture’ genre which has given its name to bunka-fu: -

Mizuho BK Custody and Proxy Board Lot Size List JUN 15 , 2021

Mizuho BK Custody and Proxy Board Lot Size List JUN 15 , 2021 Board Lot Stock Name (in Alphabetical Order) ISIN Code QUICK Code Size 21LADY CO.,LTD. 100 JP3560550000 3346 3-D MATRIX,LTD. 100 JP3410730000 7777 4CS HOLDINGS CO.,LTD. 100 JP3163300001 3726 A-ONE SEIMITSU INC. 100 JP3160660001 6156 A.D.WORKS GROUP CO.,LTD. 100 JP3160560003 2982 A&A MATERIAL CORPORATION 100 JP3119800005 5391 A&D COMPANY,LIMITED 100 JP3160130005 7745 ABALANCE CORPORATION 100 JP3969530009 3856 ABC-MART,INC. 100 JP3152740001 2670 ABHOTEL CO.,LTD. 100 JP3160610006 6565 ABIST CO.,LTD. 100 JP3122480001 6087 ACCESS CO.,LTD. 100 JP3108060009 4813 ACCESS GROUP HOLDINGS CO.,LTD. 100 JP3108190004 7042 ACCRETE INC. 100 JP3108180005 4395 ACHILLES CORPORATION 100 JP3108000005 5142 ACMOS INC. 100 JP3108100003 6888 ACOM CO.,LTD. 100 JP3108600002 8572 ACRODEA,INC. 100 JP3108120001 3823 ACTIVIA PROPERTIES INC. 1 JP3047490002 3279 AD-SOL NISSIN CORPORATION 100 JP3122030004 3837 ADASTRIA CO.,LTD. 100 JP3856000009 2685 ADEKA CORPORATION 100 JP3114800000 4401 ADISH CO.,LTD. 100 JP3121500007 7093 ADJUVANT COSME JAPAN CO.,LTD. 100 JP3119620007 4929 ADTEC PLASMA TECHNOLOGY CO.,LTD. 100 JP3122010006 6668 ADVAN CO.,LTD. 100 JP3121950004 7463 ADVANCE CREATE CO.,LTD. 100 JP3122100005 8798 ADVANCE RESIDENCE INVESTMENT CORPORATION 1 JP3047160001 3269 ADVANCED MEDIA,INC. 100 JP3122150000 3773 ADVANEX INC. 100 JP3213400009 5998 ADVANTAGE RISK MANAGEMENT CO.,LTD. 100 JP3122410008 8769 ADVANTEST CORPORATION 100 JP3122400009 6857 ADVENTURE,INC. 100 JP3122380003 6030 ADWAYS INC. 100 JP3121970002 2489 AEON CO.,LTD. 100 JP3388200002 8267 AEON DELIGHT CO.,LTD. 100 JP3389700000 9787 AEON FANTASY CO.,LTD. 100 JP3131420006 4343 AEON FINANCIAL SERVICE CO.,LTD. -

Scuola Dottorale Di Ateneo Leiden University Graduate School Insitute for Area Studies

SCUOLA DOTTORALE DI ATENEO LEIDEN UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL INSITUTE FOR AREA STUDIES DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN LINGUE E CIVILTÀ DELL’ASIA E DELL’AFRICA MEDITERRANEA CICLO 28° ANNO DI DISCUSSIONE: 2017 DECENTERING GAGAKU EXPLORING THE MULTIPLICITY OF CONTEMPORARY JAPANESE COURT MUSIC SETTORE SCIENTIFICO DISCIPLINARE DI AFFERENZA: L-OR/22 TESI DI DOTTORATO DI ANDREA GIOLAI, MATRICOLA 809041 COORDINATORE DEL DOTTORATO SUPERVISORE DEL DOTTORANDO PROF. FEDERICO SQUARCINI PROF. BONAVENTURA RUPERTI CO-SUPERVISORE DEL DOTTORANDO PROF. KATARZYNA CWIERTKA TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………i NOTE ON THE TEXT……………………ii INTRODUCTION……………………iii I. A NEW ONTOLOGICAL PARADIGM FOR THE STUDY OF ‘JAPANESE COURT MUSIC’……………iii II. “STAYING WITH THE TROUBLE”: THE CONSTITUTIVE AMBIGUITIES OF 雅楽……………x III. TELL IT LIKE IT CAN BE: GAGAKU DEFINED……………xv IV. WHERE IS GAGAKU? THICK TOPOGRAPHIES, UNCHARTED TERRITORIES……………xxv CHAPTER 1. FLOWS AND OVERFLOWS. GAGAKU’S MODES OF REPRESENTATION……………1 1.1. FIRST STREAM. THE HISTORICAL MODE……………3 1.2. SECOND STREAM. THE PRESENTATIONAL MODE ……………12 1.3. THIRD STREAM. THE MUSICOLOGICAL MODE……………19 1.4. FOURTH STREAM. THE DECENTERING MODE……………33 CHAPTER 2. IN THE LABORATORY OF MODERNITY. THE COMPLEX GENEALOGY OF 21ST-CENTURY ‘JAPANESE COURT MUSIC’……………41 2.1. THE OFFICE OF GAGAKU AND THE SCORES OF THE MEIJI……………42 2.2. THE REORGANIZATION OF COURT RITUALS AND GAGAKU AS ‘SHINTO SOUNDSCAPE’……………49 2.3. CAN THE CHILDREN SING (GAGAKU) ALONG?……………57 2.4. THE BIRTH OF ‘JAPANESE TRADITIONAL MUSIC’……………64 2.5. (COURT) MUSIC AND THE NATION……………72 CHAPTER 3. THE GAGAKU TRIANGLE. ‘COURT MUSIC’ IN KANSAI SINCE 1870……………77 3.1. CONTINUITY? THE THREE EARLY-MODERN AND MODERN OFFICES OF MUSIC……………78 3.2. -

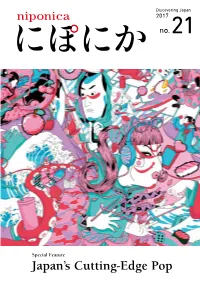

Japan's Cutting-Edge

Discovering Japan 2017 no. 21 Special Feature Japan’s Cutting-Edge Pop Discovering Japan 2017 Cover: Original illustration by KASICO, a graphic artist Special Feature who leads Japan’s pop culture scene. The composition refers to recurrence, how trends revive and live on. no. 21 Details are in the interview with KASICO on page 17. niponica is published in Japanese and six other languages (Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Japan’s Russian, and Spanish) to introduce to the world the people and culture of Japan today. The title niponica is derived from “Nippon,” the Japanese word for Japan. Cutting-Edge Pop The sweeping presence of Japan’s pop culture changes daily. Kawaii and Cool are not only unique but also offer a glimpse of Japanese tradition and style as they cast their own spell that continues to enchant the world. Contents Special Feature Japan’s Cutting-Edge Pop 04 ポップ POP ぽっぷ The Place to Meet J-Pop Culture 08 Kabukimono A New Style for JAPAN POP Artists 12 Cosplay: A Universal Language International Players Gather in Nagoya ©2016 WCS © OSAMU AKIMOTO, ATELIER BEEDAMA/SHUEISHA 14 Pop Culture Technology NEWS Next-Generation Entertainment Expands from Cutting-Edge Technologies 17 COVER ARTIST KASICO INTERVIEW From Ukiyo-e to Sushi to VR—Japanese Pop Is Tough © Artist Room Otafuku Face / AKI KONDO 18 Between Reality and Fiction Anime Pilgrimage to a Special Place in the Heart ©Taku Fujii © 2016 “Your Name.” Film Committee 22 Tasty Japan: Time to Eat! Crepes 24 Strolling Japan Hida Takayama no. 21 March 31, 2017 28 Souvenirs of Japan Pochi Bukuro Published by: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 2-2-1 Kasumigaseki, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-8919, Japan http://www.mofa.go.jp/ 02 03 The Place to Meet J-Pop Culture KAWAII A monster that swallows everything whole Experienceon athat blast street of J-Pop in that culture city It’s like a toy chest bursting with color— Let’s have fun and open it ! Colorful and Bright HARAJUKU KAWAII MONSTER CAFE HARAJUKU is a restaurant presenting Harajuku Kawaii culture to the world.