Surviving and Thriving in the Face of Rising Seas (2015) -- Full Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Equity: a Guide for Local Health Departments” Is a Product of the Public Health Institute Center for Climate Change and Health

Climate Change, Health, and A Guide For Local Equity: Health Departments Authors Contributors Linda Rudolph, MD, MPH Heather Kuiper, PhD, MPH Catherine Harrison, RN, MPH Zachariah Baker, JD Laura Buckley, MPH Neil Maizlish, PhD, MPH Savannah North, MPH Elsie Moore, MPH Acknowledgements “Climate Change, Health, and Equity: A Guide for Local Health Departments” is a product of the Public Health Institute Center for Climate Change and Health. “Climate Change, Health, and Equity: A Guide for Local Health Departments” was developed under Agreement #16-11001 with the California Department of Public Health Office of Health Equity and with funding from the American Public Health Association. Additional support was provided by The Kresge Foundation. This guide was designed by Amy Weiher at Weiher Creative, Inc. and was edited by Ann Greenberger at Greenline Editing. The authors wish to give special appreciation to the local health departments that have worked to integrate climate change into their work, and shared their experiences with the authors. Their work has inspired us to help others become more engaged in this urgent and critical issue. A special thanks to our reviewers: Charles Benjamin Beard, MS, PhD Chelsea Gridley-Smith, PhD Olubukolami Musa, MPH Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Association of City and County American Public Health Association Health Officials Andrew Deckert, MD, MPH Kate Robb, MSPH Public Health Officer, Shasta County Linda Helland, MPH American Public Health Association California Department of Public -

National Weather Service Reference Guide

National Weather Service Reference Guide Purpose of this Document he National Weather Service (NWS) provides many products and services which can be T used by other governmental agencies, Tribal Nations, the private sector, the public and the global community. The data and services provided by the NWS are designed to fulfill us- ers’ needs and provide valuable information in the areas of weather, hydrology and climate. In addition, the NWS has numerous partnerships with private and other government entities. These partnerships help facilitate the mission of the NWS, which is to protect life and prop- erty and enhance the national economy. This document is intended to serve as a reference guide and information manual of the products and services provided by the NWS on a na- tional basis. Editor’s note: Throughout this document, the term ―county‖ will be used to represent counties, parishes, and boroughs. Similarly, ―county warning area‖ will be used to represent the area of responsibility of all of- fices. The local forecast office at Buffalo, New York, January, 1899. The local National Weather Service Office in Tallahassee, FL, present day. 2 Table of Contents Click on description to go directly to the page. 1. What is the National Weather Service?…………………….………………………. 5 Mission Statement 6 Organizational Structure 7 County Warning Areas 8 Weather Forecast Office Staff 10 River Forecast Center Staff 13 NWS Directive System 14 2. Non-Routine Products and Services (watch/warning/advisory descriptions)..…….. 15 Convective Weather 16 Tropical Weather 17 Winter Weather 18 Hydrology 19 Coastal Flood 20 Marine Weather 21 Non-Precipitation 23 Fire Weather 24 Other 25 Statements 25 Other Non-Routine Products 26 Extreme Weather Wording 27 Verification and Performance Goals 28 Impact-Based Decision Support Services 30 Requesting a Spot Fire Weather Forecast 33 Hazardous Materials Emergency Support 34 Interactive Warning Team 37 HazCollect 38 Damage Surveys 40 Storm Data 44 Information Requests 46 3. -

Hazardous Weather Hazardous Weather

Texas Division of Emergency Management Texas State Operations Center Situation Awareness Brief Sunday, May 3rd, 2021 As of 0900 CST Incidents Reported to the State Operations Center (last 24 hours) Final DATE SUBJECT LOCATION Report (Y/N) 05/02/21 Initial Report of a Road Closure (US281) Live Oak County N 05/03/21 Preliminary Earthquake Report (M3.4) Culberson County Y 05/03/21 Final Report of a Road Closure (US 281) Live Oak County Y Informational Products Distributed by the State Operations Center DATE SUBJECT 05/03/21 CLEAR Alert Discontinuation - The Colony PD - Walker 05/03/21 AMBER Alert Activation - Austin PD - Wyatt Crowley 05/03/21 CLEAR Alert Activation - Allen Police Department - Bracey 05/03/21 NWS Shreveport Severe Weather Tonight and Tuesday 050321 05/02/21 20-0003 COVID-19 2020 SITREP 409 05/03/21 21-0003 February Winter WEATHER 2021 SITREP 74 Weather Forecast Highs Lows Weather Forecast Wind Speeds Gusts Hazardous Weather Hazardous Weather A High Wind Warning is in effect for Guadalupe Severe thunderstorms are possible this afternoon Pass late this evening through tonight. into this evening across eastern and southern Oklahoma and north Texas. There is the potential for hail up to the size of baseballs and thunderstorm wind gusts of 60 to 80 mph. The tornado risk is still very low and generally confined to southeast Oklahoma. Hazardous Weather Severe storms will be possible this evening and Thunderstorms are expected to move into our early tonight across the northern Big Country, northwest zones later this evening through the to the north of a Hamlin to Albany line. -

Unit, District, and Council General and Contingency Planning Guide for Boy Scouts of America©

Doctorial Project for Completion of the Degree Doctorate, Commissioner’s Science Boy Scouts of America University of Scouting Commissioner’s College Unit, District, and Council General and Contingency Planning Guide for Boy Scouts of America© Version 0.99b 4 February 2010 By Larry D. Hahn, Lt Col, USAF Ret Unit Commissioner Chesapeake Bay District Colonial Virginia Council 2010 - BSA General n Contingency Planning Guide - L. Hahn.docx Approval Letter Advisor Memorandum for Record To: Larry D. Hahn, Unit Commissioner (Doctorial Candidate) From: Ronald Davis, District Commissioner (Candidate’s Advisor) CC: Lloyd Dunnavant, Dean, Commissioners College Date: January 10, 2019 Re: Approval of BSA Scout University Doctorial Project After careful review of the submitted project from Larry D. Hahn for completion of his Commissioner’s College doctorial degree, I grant my approved and acceptance for the degree of Doctorate (PhD) in Commissioner’s Science through the Boy Scouts of America, University of Scouting. As of this date, and as his advisor, I submit this signed letter as official documentation of approval. Ronald Davis Advisor Chesapeake Bay District Commissioner Approval Letter Council Commissioner Memorandum for Record To: Larry D. Hahn, Unit Commissioner (Doctorial Candidate) From: Mike Fry, Council Commissioner CC: Ronald Davis, District Commissioner (Candidate’s Advisor) Date: January 10, 2019 Re: Approval of BSA Scout University Doctorial Project After careful review of the submitted project from Larry D. Hahn for completion of his Commissioner’s College doctorial degree, I grant my approved and acceptance for the degree of Doctorate (PhD) in Commissioner’s Science through the Boy Scouts of America, University of Scouting. -

National Weather Service Reference Guide

National Weather Service Reference Guide Purpose of this Document he National Weather Service (NWS) provides many products and services which can be T used by other governmental agencies, Tribal Nations, the private sector, the public and the global community. The data and services provided by the NWS are designed to fulfill us- ers’ needs and provide valuable information in the areas of weather, hydrology and climate. In addition, the NWS has numerous partnerships with private and other government entities. These partnerships help facilitate the mission of the NWS, which is to protect life and prop- erty and enhance the national economy. This document is intended to serve as a reference guide and information manual of the products and services provided by the NWS on a na- tional basis. Editor’s note: Throughout this document, the term ―county‖ will be used to represent counties, parishes, and boroughs. Similarly, ―county warning area‖ will be used to represent the area of responsibility of all of- fices. The local forecast office at Buffalo, New York, January, 1899. The local National Weather Service Office in Tallahassee, FL, present day. 2 Table of Contents Click on description to go directly to the page. 1. What is the National Weather Service?…………………….………………………. 5 Mission Statement 6 Organizational Structure 7 County Warning Areas 8 Weather Forecast Office Staff 10 River Forecast Center Staff 13 NWS Directive System 14 2. Non-Routine Products and Services (watch/warning/advisory descriptions)..…….. 15 Convective Weather 16 Tropical Weather 17 Winter Weather 18 Hydrology 19 Coastal Flood 20 Marine Weather 21 Non-Precipitation 23 Fire Weather 24 Other 25 Statements 25 Other Non-Routine Products 26 Extreme Weather Wording 27 Verification and Performance Goals 28 Impact-Based Decision Support Services 30 Requesting a Spot Fire Weather Forecast 33 Hazardous Materials Emergency Support 34 Interactive Warning Team 37 HazCollect 38 Damage Surveys 40 Storm Data 44 Information Requests 46 3. -

REFERENCE SHEET for NWS TAUNTON WARNING/ADVISORY THRESHOLDS (Last Updated: March 7, 2017)

REFERENCE SHEET FOR NWS TAUNTON WARNING/ADVISORY THRESHOLDS (Last Updated: March 7, 2017) The following are National Weather Service criteria for issuing Watches/Warnings/Advisories: Watches: 50% confidence of meeting Warning criteria (generally within 36-48+ hours). Advisories and Warnings: 80% confidence in the event occurrence (generally within 24-36 hours). TYPE OF ISSUANCE WHEN ISSUED FOR SOUTHERN NEW ENGLAND WINTER WEATHER ADVISORY More than one predominant hazard Winter weather event having more than one predominant hazard (ie., snow and ice, snow and sleet, or snow, ice & sleet) meeting or exceeding advisory criteria for at least one of the precipitation elements, but remaining below warning criteria. Snow, Ocean Effect Snow, and/or Sleet 3 inches averaged over a forecast zone in 12 hours Snow and Blowing Snow Sustained or frequent gusts of 25 to 34 mph accompanied by falling and blowing snow occasionally reducing visibility to ≤ 1/4 mile for ≥ 3 hours Blowing Snow Widespread or localized blowing snow reducing visibility to ≤ ¼ mile with winds < 35 mph Black Ice A Special Weather Statement will usually be issued when sufficient moisture is expected to cause a thin layer of ice on road surfaces, typically on cloudless nights (“black ice”). At forecaster discretion a formal Winter Weather Advisory may be issued instead. FREEZING RAIN ADVISORY Any accretion of freezing rain or freezing drizzle on road surfaces WIND CHILL ADVISORY Wind chill index between -15°F and -24°F for at least 3 hours using only the sustained wind WINTER STORM WARNING More than one predominant hazard Winter weather event having more than one predominant hazard {ie. -

National Weather Service Text Product Display

3/12/2014 National Weather Service Text Product Display National Weather Service National Headquarters National Weather Service Area Forecast Discussion Issued by NWS Sterling, VA Current Version | Previous Version | Text Only | Print | Product List | Glossary Off Versions: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 -- Highlight Changed Discussion -- 000 FXUS61 KLWX 121343 AFDLWX AREA FORECAST DISCUSSION NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE BALTIMORE MD/WASHINGTON DC 943 AM EDT WED MAR 12 2014 .SYNOPSIS... A STRONG LOW PRESSURE CENTER AND ITS ASSOCIATED COLD FRONT WILL PASS THROUGH THE MID-ATLANTIC STATES THIS AFTERNOON AND EVENING. AN UPPER LEVEL TROUGH WILL MOVE ACROSS THE AREA TONIGHT...THEN CANADIAN HIGH PRESSURE WILL BUILD THROUGH THURSDAY NIGHT BEFORE MOVING OFF THE COAST FRIDAY. AN UPPER LEVEL TROUGH WILL PERSIST OVER THE REGION THIS WEEKEND...AND A WEAK COLD FRONT WILL DROP THROUGH THE MID ATLANTIC ON SATURDAY. && .NEAR TERM /UNTIL 6 PM THIS EVENING/... WE SOMETIMES SAY THE FORECAST HAS SOMETHING FOR EVERYONE. I THINK WE CAN TAKE THAT LITERALLY AT THE MOMENT...AS THIS FORECAST HAS ALMOST EVERY POSSIBLE WEATHER TYPE/HAZARD...IN THE FIRST 36 HOURS. STRONG TO SEVERE STORMS...SNOW...WIND CHILLS...STRONG WINDS... UNSEASONABLY WARM TEMPS...UNSEASONABLY COLD TEMPS...POTENTIAL FIRE WEATHER CONCERNS...MINOR COASTAL FLOOD POTENTIAL...THERE IS NOT MUCH LEFT. SURFACE ANALYSIS THIS MORNING SHOWS LOW PRESSURE JUST EAST OF CINCINNATI MOVING EASTWARD AND DEEPENING...NOW DOWN TO 989 MB. CLOUD COVER HAS OVERSPREAD THE MID-ATLANTIC THIS MORNING...THOUGH VISIBLE SATELLITE DOES SHOW SOME CLEAR PATCHES MAINLY WEST OF THE BLUE RIDGE. -

10-320 Surf Zone Forecast and Coastal/Lakeshore Hazard Services

Department of Commerce • National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration • National Weather Service NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE INSTRUCTION 10-320 MAY 14, 2020 Operations and Services Marine And Coastal Weather Services, NWSPD 10-3 SURF ZONE FORECAST AND COASTAL/LAKESHORE HAZARD SERVICES NOTICE: This publication is available at: http://www.nws.noaa.gov/directives/. OPR: W/AFS26 (J. Kuhn) Certified by: W/AFS26 (M. Angove) Type of Issuance: Unscheduled SUMMARY OF REVISIONS: This instruction supersedes NWSI 10-320, “Surf Zone Forecast and Coastal/Lakeshore Hazard Services”, dated December 30, 2019. This instruction includes the following changes: Updated sections 2.3.3, 2.4, 2.6, 2.7 for reformatting of the Surf Zone Forecast Updated Appendix A Surf Zone Forecast examples. Digitally signed by STERN.ANDREW STERN.ANDREW.D.1382920348 .D.1382920348 Date: 2020.04.30 12:09:45 -04'00' 4/30/2020 Andrew D. Stern Date Director, Analyze, Forecast, and Support Office NWSI 10-320 MAY 14, 2020 Surf Zone Forecast and Coastal/Lakeshore Hazard Services Table of Contents: Page 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 4 2 Surf Zone Forecast (product category SRF) ............................................................................ 4 2.1 Mission Connection .......................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Issuance Guidelines ......................................................................................................... -

Farmers Market Vendor Regulations

Christiansburg Farmers Market Regulations The mission of the Christiansburg Farmers Market is to provide convenient access to fresh, agricultural-based foods and products to the Christiansburg community and surrounding area. Its mission also is to provide a direct sales outlet for local farmers and agricultural-product producers. The Christiansburg Farmers Market aims to foster community engagement through programs and events that promote healthy eating, nutritional education and sustainability, while contributing to a vibrant downtown by serving as a community-gathering place. Thank you for your interest in becoming a vendor at the Christiansburg Farmers Market. If you have any questions or concerns, please contact the Christiansburg Parks and Recreation Department at [email protected] or (540) 382-2349. FARMERS MARKET ELIGIBILITY Participation is open to regional Virginia growers, harvesters, bakers and makers of prepared food (hereafter, referred to as “the vendors”). The Market strives to be a producers-only market but may make some exceptions. Vendors must participate in the production of the product they sell and all products must be locally produced. Locally produced is defined by a 100-mile radius of the Christiansburg Recreation Center (1600 N. Franklin St.), though sale of agricultural products outside the 100-mile radius may be permitted as determined by the Central Business District Committee. Determination of eligibility is made by the Market Manager. No political party or political-affiliated vendors are permitted per Town policy. MARKET DATES, DAY & HOURS OF OPERATIONS The Christiansburg Farmers Market (hereafter, referred to as “the Market”) will be open, rain or shine, on Thursdays, May through October from 3 to 7 p.m., though the Farmers Market hours may be adjusted and/or extended in relation to busy growing season. -

Blizzard Warning for CT Coast; Wind and 10-16 Inches of Snow Forecast; Cttransit Suspending Bus Service

Darienite News for Darien https://darienite.com Blizzard Warning for CT Coast; Wind and 10-16 Inches of Snow Forecast; CTTransit Suspending Bus Service Author : David Gurliacci Categories : Weather Tagged as : January 2016 Blizzard Date : January 23, 2016 The National Weather Service has issued a Blizzard Warning for most of the New York Metropolitan region and Connecticut's Long Island Coast and says Darien could be under 10 to 16 inches of snow through Saturday night, with blustery winds and dangerous travel conditions. Traveling roads could be "extremely dangerous" and the wind could cause power outages, the weather service says in the Blizzard Warning issued at 4 a.m. and in effect through 7 a.m. Sunday: EXTREMELY DANGEROUS TRAVEL DUE TO HEAVY SNOWFALL AND STRONG WINDS WITH WHITEOUT CONDITIONS LIKELY. SECONDARY AND TERTIARY ROADS MAY BECOME I MPASSABLE. STRONG WINDS MAY DOWN POWER LINES AND TREE LIMBS. 1 / 8 Darienite News for Darien https://darienite.com If an event in town has been scheduled for Saturday, assume it's cancelled. Report Any Downed Wires and Power Outages An update at 8:40 p.m. — Eversource has announced: "Remember: Always stay away from downed lines & report to 9-1-1. Report power outages to 1-800-286-2000 or online." UPDATES here: 5:22 p.m.: Here's the Latest Darien-specific forecast from the National Weather Service as of 3;56 p.m.: This Afternoon Snow. The snow could be heavy at times. Some thunder is also possible. High near 30. Wind chill values between 15 and 20. Windy, with a northeast wind around 33 mph. -

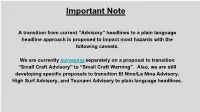

Side by Side Comparison for Advisory Products

Important Note A transition from current “Advisory” headlines to a plain language headline approach is proposed to impact most hazards with the following caveats. We are currently surveying separately on a proposal to transition “Small Craft Advisory” to “Small Craft Warning”. Also, we are still developing specific proposals to transition El Nino/La Nina Advisory, High Surf Advisory, and Tsunami Advisory to plain language headlines. Full list of Current NWS Advisories (Examples of proposed transition to plain language headlines on subsequent slides) Winter Weather Advisory Lake Wind Advisory Air Stagnation Advisory High Surf Advisory Wind Chill Advisory Frost Advisory El Nino/La Nina Advisory Small Craft Advisory Dense Fog Advisory Blowing Dust Advisory Tsunami Advisory Lakeshore Flood Advisory Dense Smoke Advisory Dust Advisory Freezing Spray Advisory Coastal Flood Advisory Wind Advisory Ashfall Advisory Low Water Advisory Flood Advisory Heat Advisory Freezing Fog Advisory Brisk Wind Advisory* Flood Advisory (River) *Only issued in Alaska Region Winter Weather Advisory Current Proposed WSWABQ WSWABQ URGENT - WINTER WEATHER MESSAGE Winter Weather Message National Weather Service Albuquerque NM National Weather Service Albuquerque NM 343 AM MDT Tue Oct 29 2019 343 AM MDT Tue Oct 29 2019 NMZ227-228-230-291800- NMZ227-228-230-291800- /O.NEW.KABQ.WW.Y.0023.191030T0000Z-191030T1800Z/ /O.NEW.KABQ.WW.S.0023.191030T0000Z-191030T1800Z/ [Cities and Counties] [Cities and Counties] 343 AM MDT Tue Oct 29 2019 343 AM MDT Tue Oct 29 2019 ...WINTER WEATHER ADVISORY IN EFFECT FROM 6 PM THIS EVENING TO ...Light snow accumulations expected from 6 PM this evening to NOON MDT WEDNESDAY.. -

National Weather Service Warning Thresholds

NWS WARNINGS AND ADVISORIES FOR SOUTHERN NEW ENGLAND (Last Updated: December 4, 2015) The following are National Weather Service criteria for issuing Watches/Warnings/Advisories: Watches: 50% confidence of meeting Warning criteria (generally within 36-48+ hours). Advisories and Warnings: 80% confidence in the event occurrence (generally within 24-36 hours). TYPE OF ISSUANCE WHEN ISSUED FOR SOUTHERN NEW ENGLAND WINTER WEATHER ADVISORY More than one predominant hazard • Winter weather event having more than one predominant hazard (ie., snow and ice, snow and sleet, or snow, ice & sleet) meeting or exceeding advisory criteria for at least one of the precipitation elements, but remaining below warning criteria. Snow, Ocean Effect Snow, and/or Sleet • 3 inches averaged over a forecast zone in 12 hours (except 4 inches in Berkshire/Litchfield Counties) Snow and Blowing Snow • Sustained or frequent gusts of 25 to 34 mph accompanied by falling and blowing snow occasionally reducing visibility to ≤ 1/4 mile for ≥ 3 hours ` Blowing Snow • Widespread or localized blowing snow reducing visibility to ≤ ¼ mile with winds < 35 mph Black Ice • A Special Weather Statement will usually be issued when sufficient moisture is expected to cause a thin layer of ice on road surfaces, typically on cloudless nights (“black ice”). At forecaster discretion a formal Winter Weather Advisory may be issued instead. FREEZING RAIN ADVISORY Any accretion of freezing rain or freezing drizzle on road surfaces WIND CHILL ADVISORY Wind chill index between -15°F and -24°F for at least 3 hours using only the sustained wind WINTER STORM WARNING More than one predominant hazard • Winter weather event having more than one predominant hazard {ie.