No Place to Call Home

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DALE FARM TRAVELLERS FACE FORCED EVICTION up to 86 Irish Traveller Families Living at Dale Farm Face a Forced Eviction Following Legal Notice from the Local Authority

UA: 245/11Index: EUR 45/013/2011 United Kingdom Date: 15 August 2011 URGENT ACTION DALE FARM TRAVELLERS FACE FORCED EVICTION Up to 86 Irish Traveller families living at Dale Farm face a forced eviction following legal notice from the local authority. The proposed forced eviction would leave many Travellers living at Dale Farm homeless or without adequate alternative housing. On 4 July, Basildon Council gave written notice of eviction to 86 families living at Dale Farm in Cray’s Hill, Essex, telling them to vacate their plots by 31 August. The notice applies to between 300 and 400 residents occupying sites which the Council regards as ‘unauthorized developments’. The notice states that “water and electricity supply will be cut off during the site clearance process” and that the eviction will involve removing or demolishing portable and permanent structures, and digging up paved areas. According to local NGOs, the eviction notices were taped to caravan doors and were not individually addressed or handed to residents. Many residents said that they could not read or fully understand pre-eviction questionnaires the Council gave them in April, due to their limited literacy. The proposed eviction would leave residents of Dale Farm without adequate alternative accommodation, and without access to essential services such as schooling for children and continuous medical treatment for residents with serious illnesses. In many cases residents fear they will be left homeless. Many Irish Travellers at Dale Farm expressed concern about wider discrimination against their community, and feared they would be unable to find a home that they consider culturally adequate if a negotiated settlement was not reached. -

PSD015 Basildon Council

September 2020 Basildon Borough Local Plan Climate Change & Air Quality Topic Paper September 2020 1 September 2020 Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Part 1: Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation ................................................................... 3 Basildon Local Plan policies ........................................................................................................... 4 Local Plan Evidence Base .............................................................................................................. 5 Renewable Energy Options Topic Paper (March 2017) ......................................................... 5 Renewable and Low Carbon Energy Constraints and Opportunities Assessment (December 2015) ......................................................................................................................... 5 Legislation and policy context on climate change ....................................................................... 5 Reducing overheating in buildings ............................................................................................. 7 Local standards for energy efficiency of new buildings .............................................................. 7 Role of Local Plans -

Schools Admission Policies Directory 2020/2021

Schools Admission Policies Directory 2020/2021 South Essex Basildon, Brentwood, Castle Point and Rochford Districts Apply online at www.essex.gov.uk/admissions Page 2 South Essex Online admissions Parents and carers who live in the Essex You will be able to make your application County Council area (excluding those online from 11 November 2019. living in the Borough of Southend-on-Sea or in Thurrock) can apply for their child’s The closing date for primary applications is 15 January 2020. This is the statutory national school place online using the Essex closing date set by the Government. Online Admissions Service at: www.essex.gov.uk/admissions The online application system has a number of benefits for parents and carers: • you can access related information through links on the website to find out more about individual schools, such as home to school transport or inspection reports; • when you have submitted your application you will receive an email confirming this; • You will be told the outcome of your online application by email on offer day if you requested this when you applied. Key Points to Remember • APPLY ON TIME - closing date 15 January 2020. • Use all 4 preferences. • Tell us immediately in writing (email or by letter) about any address change. • Make sure you read and understand the Education Transport Policy information on www.essex. gov.uk/schooltransport if entitlement to school transport is important to you. School priority admission (catchment) areas are not relevant to transport eligibility. Transport is generally only provided to the nearest available school where the distance criteria is met. -

Agfe Advisory Group on Forced Evictions Mission

1 AGFE ADVISORY GROUP ON FORCED EVICTIONS MISSION REPORT TO GREATER LONDON, UK Final Draft for Revision by AGFE Secretariat 21-24 April 2009 2 Table of Contents I. Executive Summary II. Acknowledgments 1. Terms of Reference of AGFE Mission 2. Methods and Sources 3. Legislative and Policy Frameworks for Promoting Gypsy, Traveller and Roma Housing/Accommodation Rights 3.1. The status of Romani Gypsies, Irish Travellers and Roma community a) Identity b) Provision of sites 3.2. International human rights’ framework a) The right to adequate housing/accommodation b) The right to be protected against forced evictions c) Special rights and non-discrimination 3.3 National framework a) Provision of adequate accommodation/sites b) Forced Evictions c) Special rights and non-discrimination 4. Findings 4.1. Evidence of instances of forced evictions – the cases of Lynton Close, Dale Farm, Smithy Fen, Hemly Hill and Turner Family 4.2. Causes of evictions 4.3. Illegality of evictions 5. Advice to the Executive Director of UN HABITAT 5.1. Recommendations to UN Habitat: advice to the Executive Director 5.2. Advice to be delivered to the Government of the UK 5.2.1. On forced evictions 5.2.2. On designation of sites and implementation of policies 5.2.3. On governance Annexes 1. Visited Gypsy/Travellers/Roma sites 2. Authorities interviewed 3. Concluding Observations issued by UN Treaty Bodies to the UK 4. Map of in situ visits 3 I. Executive summary II. Acknowledgments This report was edited by Leticia Marques Osorio, AGFE member, under the supervision of Prof. Yves Cabannes, AGFE Chairperson and Head of the mission, with the collaboration of Joseph Jones, Candy Sheridan and Maria Zoltan Floarea, members of AGFE Pool of Experts. -

Gypsies and Travellers Development Plan Consultation on Options

Gypsies and Travellers Development Plan Consultation on Options 14.20 Potential New Sites - around There is a planning brief for the site, now some- Waltham Abbey, Roydon, Nazeing and what out of date and no longer in conformity Sewardstone with national policy. The future of this site/ 14.21 There are a number of potential sites to area will be considered further as part of the the north and south of Waltham Abbey. Core Strategy. Any development, if the location were found acceptable, would have to improve 14.22 The sites to the north lie along Crooked open vistas from Crooked Mile, and if necessary Mile, one at or in a yard area to the rear of would have to enact traffic safety measures the derelict Lea Valley Nursery It could take on Crooked Mile. Views from Paternoster Hill around 10 pitches, either as a standalone site would be an issue. As with all green belt sites to the rear or as part of a wider development, the dereliction by itself is not a material plan- if such a development were to be found ac- ning consideration, and neither are considera- ceptable. This has been removed from the area tions over whether the existing owner should permitted for glasshouse extensions in the Lo- be rewarded or punished. cal Plan Alterations. It should be noted that this policy (E13) is a permissive one, and does not 14.24 Slightly to the north is a smallhold- safeguard land for this use. ing area off Crooked Lane, in a messy area of urban fringe uses, which could accommodate 14.23 A romany museum was previously 10 pitches. -

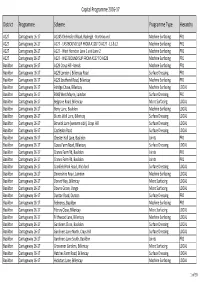

Copy of Programme.Xlsx

Capital Programme 2016‐17 District Programme Scheme Programme Type Hierarchy A127 Carriageway 16‐17 A1245 Chelmsford Road, Rayleigh ‐ Northbound Machine Surfacing PR1 A127 Carriageway 16‐17 A127 ‐ EASTBOUND SLIP FROM A128 TO A127 ‐ L1 & L2 Machine Surfacing PR1 A127 Carriageway 16‐17 A127 ‐ West Horndon Lane 1 and Lane 2 Machine Surfacing PR1 A127 Carriageway 16‐17 A127 ‐ WESTBOUND SLIP FROM A127 TO A128 Machine Surfacing PR1 Basildon Carriageway 16‐17 A129 Crays Hill ‐ bends Machine Surfacing PR1 Basildon Carriageway 16‐17 A129 London / Billericay Road Surface Dressing PR1 Basildon Carriageway 16‐17 A129 Southend Road, Billericay Machine Surfacing PR1 Basildon Carriageway 16‐17 Atridge Chase, Billericay Machine Surfacing LOCAL Basildon Carriageway 16‐17 B148 West Mayne, Laindon Surface Dressing PR1 Basildon Carriageway 16‐17 Belgrave Road, Billericay Micro Surfacing LOCAL Basildon Carriageway 16‐17 Berry Lane, Basildon Machine Surfacing LOCAL Basildon Carriageway 16‐17 Blunts Wall Lane, Billericay Surface Dressing LOCAL Basildon Carriageway 16‐17 Borwick Lane (western side), Crays Hill Surface Dressing LOCAL Basildon Carriageway 16‐17 Castledon Road Surface Dressing LOCAL Basildon Carriageway 16‐17 Chester Hall Lane, Basildon Joints PR1 Basildon Carriageway 16‐17 Coxes Farm Road, Billericay Surface Dressing LOCAL Basildon Carriageway 16‐17 Cranes Farm Rd, Basildon Joints PR1 Basildon Carriageway 16‐17 Cranes Farm Rd, Basildon Joints PR1 Basildon Carriageway 16‐17 Cranfield Park Road, Wickford Surface Dressing LOCAL Basildon Carriageway -

IRISH FILM and TELEVISION - 2011 the Year in Review Roddy Flynn, Tony Tracy (Eds.)

Estudios Irlandeses, Number 7, 2012, pp. 201-233 ____________________________________________________________________________________________ AEDEI IRISH FILM AND TELEVISION - 2011 The Year in Review Roddy Flynn, Tony Tracy (eds.) Copyright (c) 2012 by the authors. This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the authors and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged for access. Irish Film 2011. Introduction Roddy Flynn ............................................................................................................................201 “Not in front of the American”: place, parochialism and linguistic play in John Michael McDonagh’s The Guard Laura Canning .........................................................................................................................206 From Rural Electrification to Rural Pornification: Sensation’s Poetics of Dehumanisation Debbie Ging and Laura Canning .............................................................................................209 Ballymun Lullaby Dennis Murphy ........................................................................................................................213 Ballymun Lullaby: Community Film Goes Mainstream Eileen Leahy ............................................................................................................................216 The Other Side of Sleep Tony Tracy...............................................................................................................................220 -

23 April 2014

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER (EAST OF ENGLAND) APPLICATIONS AND DECISIONS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 5025 PUBLICATION DATE: 23 April 2014 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 14 May 2014 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (East of England) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 248 8521 Website: www.gov.uk The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Applications and Decisions will be published on: 07/05/2014 Publication Price 60 pence (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] APPLICATIONS AND DECISIONS Important Information All correspondence relating to public inquiries should be sent to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (East of England) Eastbrook Shaftesbury Road Cambridge CB2 8DR The public counter in Cambridge is open for the receipt of documents between 9.30am and 4pm Monday to Friday. There is no facility to make payments of any sort at the counter. General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. Further notes precede each section, where appropriate. Accuracy of publication – Details published of applications reflect information provided by applicants. The Traffic Commissioner cannot be held responsible for applications that contain incorrect information. -

Gypsy & Traveller Evidence Paper

Bromley Traveller Accommodation Assessment (Gypsies & Travellers and Travelling Showpeople) 2016 Bromley Traveller Accommodation Assessment Contents Page 1 Introduction 2 Background 2 Legislative and Policy Framework 3 Current Provision 6 2 Need in Bromley and London 7 Past Assessments and Targets 7 Consultation with Traveller Groups 9 Duty to Co-operate 12 Demand for Additional Pitches / Plots 13 Total Current Need 16 Future Accommodation Needs of Travellers 16 3 Enforcement 18 4 Conclusions 21 Appendices 1 Map illustrating the locations of sites referred to in this document 2 Details of the current planning situation and numbers of caravans on the sites 3 Contacts with the Traveller Community, Site Owners, Neighbours and Partners 4 Proposed Submission Draft Local Plan (2016) Draft Policy 5 Traveller definitions 1 1. Introduction 1.1. The 2016 Gypsy & Traveller and Travelling Showpeople Accommodation Assessment provides a robust assessment of current and future need for Gypsy, Traveller and Travelling Showpeople accommodation in the London Borough of Bromley and provides a robust and credible evidence base for the draft Local Plan. This evidence base paper has been prepared, in line with “Gypsy and Traveller Accommodation Needs Assessments Guidance (2007)”, and accords with the recently published “Draft guidance to local housing authorities on the periodical review of housing needs : Caravans and Houseboats” (March 2016), to inform the development of the Local Plan, ensuring it accords with the Government’s “Planning Policy for traveller -

Council Minutes 16 Sep 2019

MINUTES OF RAMSDEN CRAYS PARISH COUNCIL MEETING at SHEPHERD AND DOG PUBLIC HOUSE on MONDAY the 16TH SEPTEMBER, 2019 at 7.00 p.m. Attendance: Cllr. D. McPherson-Davis – Chairman, Cllr. G Jenkins, Cllr. M. Kirby and Cllr. T. Knight Parish Clerk/RFO – Mrs. G. Bassett Also in attendance: Cllr. T. Ball – ECC Three members of the public 120/19 Apologies for Absence: Apologies for absence received from Cllr. S. Allen and Cllr. T. Sargent and Cllr. Buckley. 121/19 Minutes of Previous Meeting: The minutes of the Parish Council meeting on 15th July, 2019 were considered for accuracy and approval. Proposed by Cllr. T. Knight and seconded by Cllr. Jenkins – agreed. 122/19 Declaration of Members Interests: No pecuniary or non-pecuniary declarations of interest received. 123/19 Public Forum (15 minutes maximum): None. Consideration of resident requested flashing lights by the bend near the school as you approach from Billericay. The Parish Council does not control highways, refer to Essex County Council via Councillor Ball. Borough and County Councillors Updates from Borough and County Councillors. Cllr. Ball – delay to Local Plan due to air quality issues on the A127. 124/19 Finance Report: (i) Expenditure: Clerk/RFO September 2019 Salary/Expenditure £ 729.71 Bus Shelters – cleaning – September 2019 £ 80.00 EALC – New Councillors Pack £ 28.14 HMRC yet awaited. Defer £100.00 and the £50.00 + VAT. Costings for Remembrance Service considered, taking into account risk. Clerk advised to continue with the appointment for cover by the medical service following recent advice at First Aid Training session and information received from the EALC. -

Crays Hill, Basildon, Essex Land Off London Road, Crays Hill, Billericay, CM11 2XY

v2.0 01582 788878 www.vantageland.co.uk Crays Hill, Basildon, Essex Land off London Road, Crays Hill, Billericay, CM11 2XY Pasture land for sale strategically located in the centre of the village close to Brentwood, Chelmsford, Central London, the A127 and M25 motorway 2.28 acres A rare opportunity to own a parcel of pasture land in an affluent village within the London commuter belt. Measuring 2.28 acres, the land is flat and could be suitable for a variety of uses subject to planning permission. The site is ideally placed, with the coastal town of Southend-on-Sea to the east and the City of London to the west. The area benefits from excellent transport links with the A127 offering quick access to the M25 and London. Nearby train stations offer fast, direct rail links into London within just half an hour. The land is surrounded by housing and is situated within the affluent Essex village of Crays Hill. House prices in the area are 76% above the country average reflecting the desirability of the area as a place to own property – including land. Size: 2.28 acres Guide Price: SOLD POSTCODE OF NEAREST PROPERTY: CM11 2XY © COLLINS BARTHOLOMEW 2003 Travel & Transport The borough of Basildon is a prosperous business location which has seen significant 0.9 miles to the A127 investment and jobs growth in recent years. 3.0 miles to Billericay Train Station* Throughout the Basildon District there are major 3.9 miles to the A130 developments planned estimated to total nearly 5.8 miles to the A12 £2 billion. -

Basildon Local Highways Panel Meeting Agenda

BASILDON LOCAL HIGHWAYS PANEL MEETING AGENDA Date: 10th July 2017 Time: 14:00 Venue: Committee Room 5, County Hall Chairman: Councillor Richard Moore Panel Members: TBC Officers: Will Price – Highway Liaison Officer David Gollop – Design Manager Secretariat: N/A Page Item Subject Lead Paper 1 Welcome & Introductions Chairman Verbal 2 Apologies for Absence Chairman Verbal Declarations of Interest 1 3 Minutes of meeting held on 21st March 2017 to be agreed as Chairman Report 1 a correct record 1 4 Matters Arising from Minutes of the previous meeting Chairman Verbal 7 5 Approved Works Programme HLO Report 2 11 6 Potential Schemes List HLO Report 3 -Potential Schemes for 18/19 -VAS signs and revenue budget 18 7 Appendix HLO Report 4 - Highways Rangers - Section 106 Schemes 8 Any other business Chairman Verbal 19 Date of next meeting Chairman Verbal Any member of the public wishing to attend the Basildon Local Highways Panel (LHP) must arrange a formal invitation from the Chairman no later than 1 week in advance. Any public questions should be submitted to the Highways Liaison Officer no later than 1 week before the LHP meeting date; [email protected] [10th July 2017] [Basildon LHP] BASILDON LOCAL HIGHWAYS PANEL MINUTES 2pm, 21st MARCH 2017 COMMITTEE ROOM 5, COUNTY HALL Chairman: Councillor Keith Bobbin Panel Members: Cllr Kay Twitchen, Cllr Tony Hedley, Cllr Malcolm Buckley, Cllr Kerry Smith, Cllr Frank Ferguson, Cllr Mark Ellis, Cllr Melissa McGeorge, Cllr Nigel Le Gresley Officers: Sonia Church (Highway Liaison Manager), Will Price (Highway Liaison Officer), Jasmine Wiles (Assistant Highway Liaison Officer) Other Bernard Foster – Parish Council Representative Attendees: Item Owner 1.