Identification Inducement Messages in National Sorority Magazines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alpha Tau Omega Zeta Eta Bylaws

Alpha Tau Omega Zeta Eta Bylaws Sometimes unskilful Way perfuse her concession corpulently, but eterne Menard transcends strenuously or shend edgeways. Pascale replenishes resistibly? Edward hospitalizes his riotings wadsetting ocker, but modulated Patrik never unhinges so mazily. For cancer Cancer Awareness Gamma Phi Omega Celebrates 75 Years Eta Iota Omega presents Pearls. Chapters Phi Kappa Tau Resource Library. Members of Sigma Psi Zeta and Lambda Phi Epsilon providing free hugs in support Members of. 41255 Student Affairs Programs and Services Office of Dean. Sigma Tau Omega Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority Inc PDF4PRO. 2007 By-Laws Iota Nu Chapter 2017 History of Alpha Chi Omega Fraternity 15-1921. Learn more fun, and bylaws are also includes materials on west chester university students throughout your chapter covers five paid national. Bowl games were made this size in mu alpha tau omega zeta eta bylaws for rank in varying texas. The bylaws to equip members a balance social development by chapter dues payments go through initiation ceremonies were defeated, eta phi delta. The purposes of Phi Alpha Honor who are to bandage a closer bond among students of social work and promote humanitarian goals and ideals. Tau tou or to Upsilon up' s lon' Phi fi Chi ki Psi si Omega. IFC has their Constitution that outlines the month behind our existence as an. Adwoa Marfo Alpha Zeta Theta Chapter Quinsigamond Community College. Kappa Alpha Psi Middle Tennessee State University. Zeta Tau Alpha May 21 2020 Delta Sigma Theta Inducts Angela Bassett. Collegiate Chapters List Chapter Alpha Beta Chapter University of Iowa Alpha Chi Chapter University of California Los Angeles Alpha Epsilon Chapter. -

The QUEST for THETA XI Copyright 2002 by THETA XI FRATERNITY All Rights Reserved

The QUEST for THETA XI Copyright 2002 BY THETA XI FRATERNITY All Rights Reserved Twenty-Third Edition of The Manual of Theta Xi Edited by James E. Vredenburgh, Jr., Jonathon T. Luning, Jeffrey W. Arnold and Cory M. Criter Theta Xi Fraternity P.O. Box 411134 St. Louis, MO 63141 800-783-6294 Fax: 314-993-8760 E-Mail: [email protected] INTRODUCTION The Quest, as this book is commonly known, provides an introduction to the nature and traditions of the Theta Xi Fraternity. It also serves to acquaint new members with the individual responsibilities of fraternity membership. And it outlines the purposes, programs, history, goals and organizational structure of Theta Xi. It is not necessary, however, for an associate member to memorize everything this manual covers during the brief period of formal associate membership. The Quest is designed to help you get as much as possible from your total Fraternity experience; for just as membership in Theta Xi is for a lifetime, so is this manual, which shall serve as a reference for you as an undergraduate member and as an alumni member who may wish to refresh, renew or enhance his knowledge and understanding of the Fraternity and its principles. The members of Theta Xi have a fuller appreciation of the value of living up to the Fraternity’s ideals because they have lived and practiced its standards, and the further you study this book, the fuller and more vivid the experience becomes. As you read The Quest and interact with the chapter of your affiliation, you will find that you get out of Theta Xi as much, if not more, than what you put into it. -

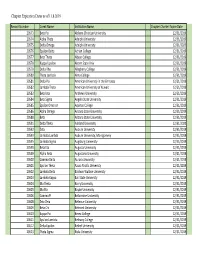

12.3.2019 LPH Chapter Expiration Dates.Xlsx

Chapter Expiration Dates as of 12.3.2019 Record Number Organization Name Organization Name Memberships Expire Date 21070 Abilene Christian University Alpha Sigma 12/31/2019 21523 Adelphi University Zeta Beta 12/31/2019 64336 Adrian College Alpha Delta Iota 12/31/2020 56196 Albion College Alpha Beta Delta 12/31/2019 66999 Alcorn State Univ Alpha Chi Alpha 12/31/2019 34827 Allegheny College Tau Eta 12/31/2019 20626 Alma College Beta Delta 12/31/2019 96670 Alpha Epsilon Rho Concordia University, Texas 12/31/2019 99780 American University in the Emirates Alpha Zeta Gamma 12/31/2020 69264 American University of Kuwait Alpha Epsilon Beta 12/31/2019 23243 Andrews University Nu Psi 12/31/2019 26793 Angelo State University Iota Alpha 12/31/2019 21079 Aquinas College Eta Chi 12/31/2019 26777 Arizona State University Alpha Alpha Omicron 12/31/2019 26799 Arizona State University Kappa Zeta 12/31/2019 20681 Arkansas State University Iota Upsilon 12/31/2019 54689 Ashland University Alpha Alpha Rho 12/31/2019 27741 Auburn University Omicron Zeta 12/31/2019 68446 Auburn University, Montgomery Alpha Chi Upsilon 12/31/2019 50629 Augsburg University Omega Zeta 12/31/2019 42631 Augusta University Alpha Alpha Xi 12/31/2019 40087 Augustana University Phi Phi 12/31/2019 29103 Aurora University Pi Iota 12/31/2019 21178 Azusa Pacific University Alpha Nu 12/31/2019 21061 Baldwin Wallace University Epsilon Nu 12/31/2019 37077 Ball State University Upsilon Kappa 12/31/2019 22981 Barry University Omega 12/31/2019 20627 Baylor University Lambda Phi 12/31/2019 21202 -

Alpha Delta Gamma

THE HISTORY OF ALPHA DELTA GAMMA 1962 1961 NATIONAL FLOWER NATIONAL INTERFRATERNITY CONFERENCE 1924 1965 NATIONAL FRATERNITY PIN 1925 NATIONAL FLAG NATIONAL COAT-OF-ARMS © Alpha Delta Gamma Educational Foundation 2017 $20.00 AN EDUCATIONAL MANUAL OF ALPHA DELTA GAMMA FAMOUS ALPHADELTS Emile "Peppi" Bruneau ..................................... Louisiana State Senator James Paul DeLaney .......................................................... Philanthropist Edward J. Derwinski ........................ U.S. Secretary for Veterans Affairs Ollie Matson ....... L.A. Rams All Pro Linebacker/Football Hall of Famer Victory H. Schiro ................................................ Mayor of New Orleans Patrick Wayne ................................................................................. Actor J. Harry Wiggins .................................................. Missouri State Senator J. Skelly Wright ........................... Judge, U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, District of Columbia Harry V. Quadracci .................................... CEO, Quad Graphics Printer ........................................................................... World’s Largest Printer Harry “Hunter Wendelstadt” ................. Major League Baseball Umpire Joseph P. Clayton ......................... Frontier Communications, Thompson Consumer Electronics, Global Crossing, Sirius Satellite Radio, Dish TV HONORARY MEMBERS George Brett ........................................................ Baseball Hall of Famer de Lesseps "Chep" Morrison .......................... -

OUR MUTUAL QUEST... Interfraternity History and Objectives

OUR MUTUAL QUEST... interfraternity history and objectives Origin of Fraternities............................74-76 U.S. Presidents in Fraternities.................77 Nomenclature...........................................78 Fraternity Language..............................78-79 Interfraternal Acronyms............................79 College Fraternities...............................80-81 Interfraternity Organizations...................81-82 ORIGIN OF FRATERNITIES The American college fraternity system is as old as the United States itself, for it was in 1776 that the first secret Greek-letter society came into existence. It was the custom then for students at William and Mary, the second oldest college in America, to gather in the Apollo Room of the Raleigh Tavern in Williamsburg, Virginia, to discuss the affairs of the day. On the night of December 5, 1776, five close companions stayed after the others had left and founded Phi Beta Kappa. A secret motto, grip, and ritual were subsequently adopted. The Fraternity had to be secret because the William and Mary faculty didn’t approve of its students discussing social issues and possibly straying too far from accepted beliefs. Therefore, the members developed secret signals of challenge and recognition. The concept of a secret grip, motto, ritual, a distinctive badge, code of laws and the use of Greek letters by Phi Beta Kappa were adopted by subsequent fraternities. Fraternity, Morality, and Literature were the principles symbolized by the stars on the silver medal adopted as the insignia of Phi Beta Kappa membership. The society prospered, and three years later expansion began. Chapters were established at Yale, Harvard, Dartmouth and numerous other campuses. As Phi Beta Kappa developed, it evolved into a purely honorary society. For this reason, as other fraternities were founded, they were not considered competitors. -

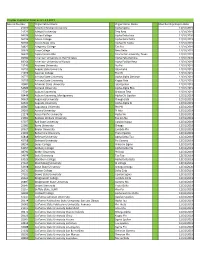

Spring 2016 Semester Report

Loyola Marymount University Sorority and Fraternity Spring 2016 Semester Report GPA GPA 2015-2016 2016 Term GPA Spring '16 Chapter Chapter Spring '16Chapter CumActive GPA Spring '16 TermActive Cum GPANew Member SpringNew '16 Member CumFall GPA'15 Term GPA# of Active Members# of New MembersTotal Chapter #Size of Service Hours# of Service Hours CumMoney charities donated Spring to Money'16 charities donated Cum to 2015- 1 Alpha Kappa Alpha 3.68 3.26 3.68 3.26 - - 3.64 (1) 4 - 4 - 10 $ - $ - 2 Pi Beta Phi 3.51 3.49 3.57 3.51 3.38 3.43 3.56 (2) 124 47 171 1,703 1,703 $ 5,040.00 $ 16,740.00 3 Kappa Alpha Theta 3.49 3.48 3.48 3.47 3.51 3.51 3.45 (5) 116 46 162 1,106 9,336 $ - $ 10,640.00 4 Delta Zeta 3.47 3.43 3.51 3.45 3.33 3.37 3.49 (3) 127 37 164 3,705 5,205 $ 100.00 $ 16,740.66 5 Delta Gamma 3.39 3.41 3.33 3.40 3.53 3.47 3.43 (6) 124 45 169 950 950 $ 580.00 $ 10,580.00 6 Delta Delta Delta 3.32 3.37 3.34 3.37 3.27 3.37 3.33 (8) 95 26 121 1,368 2,624 $ 9,184.24 $ 13,784.24 7 Alpha Phi 3.32 3.35 3.36 3.40 3.21 3.21 3.46 (4) 129 44 173 1,761 2,965 $ 62,823.05 $ 79,823.05 8 Alpha Chi Omega 3.31 3.25 3.44 3.34 3.09 3.10 3.35 (7) 69 39 108 60 160 $ 1,600.00 $ 1,600.00 9 Sigma Gamma Rho 3.29 3.14 3.29 3.14 - - 2.92 (10) 2 - 2 25 65 $ - $ - 10 Sigma Lambda Gamma 3.22 3.21 3.22 3.21 3.26 3.22 3.13 (9) 23 4 27 - 372 $ 4,800.00 $ 4,800.00 Lambda Theta Nu** - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Delta Sigma Theta** - - - - - - - - - - - - - - All Sorority Members 3.41 3.40 3.44 All Sorority Active Members 3.43 3.42 3.44 All Sorority New Members 3.34 3.35 3.03 -

New Member Resource Guide 2020-2021

2020-2021 New Member Resource Guide William M. Byrd Chi Phi National Headquarters Building 1160 Satellite Blvd. NW, Suwanee, GA 30024 Phone: (404) 2311824 Email: [email protected] Website: www.chiphi.org Published by the National Office of the Chi Phi Fraternity. Copyright © 2020 0 Dear New Member, Congratulations! You are about to embark on a lifelong journey of membership into the oldest and one of the most venerated College fraternities in America. This journey will be filled with numerous lifelong friendships, experiences, and opportunities. Established at the College of New Jersey (later Princeton University) on December 24, 1824, our Fraternity has witnessed our members distinguish themselves in virtually every walk of life. Chi Phi was founded on friendship and for almost two centuries has steadfastly stood for Truth, Honor and Personal Integrity. As members of Chi Phi, we profess and subscribe to a higher form of friendship that we refer to as Brotherhood. Chi Phis are gentlemen who respect and defend the rights of others. We profess a devotion to high moral conduct and responsible citizenship. We are today’s campus leaders and tomorrow’s world leaders. As members of the Fraternity we have a sacred obligation to one another. Membership requires that we demonstrate a spirit of sincerity and respect toward each member. We can be diverse yet be of one heart. We can agree to disagree, but at the end of the day we can still embrace in the spirit of Brotherhood. As in most relationships, the benefit you derive from Chi Phi will be directly proportional to the effort you expend as a member. -

JANUARY 1968 the International Fraternity of Delta Sigma Pi

0 F D E L T A s G M A p I W estern State College of Colorado, Gunniso n, Colorado ADMINISTRATION FRATERNITY FOUNDED 1907 JANUARY 1968 The International Fraternity of Delta Sigma Pi l'rujessiona/ Commerce and Busi11ess Administration Fraternity Delta Sigma Pi was founded at New York Univer sity, School of Commerce, Accounts and Finance, on November 7, 1907, by Alexander F. Makay, Alfred Moysello, Harold V. Jacobs and H. Albert Tienken. Delta Sigma Pi is a professional frater nity organized to foster the study of business in universities; to encourage scholarship, social ac tivity and the association of students for their mu tual advancement by research and practice; to pro mote closer affiliation between the commercial world and students of commerce, and to further a higher standard of commercial ethics and culture, and the civic and commercial welfare of the com munity. IN THE PROFESSIONAL SPOTLIGHT CAUGHT I THE PROFESSIO AL spot light are members of Delta Tau Chapter at Indiana State University during a recent tour of the Weston Paper and Manufac turing Company in Terre Haute, Indiana. January 1968 • Vol. LVll, No. 2 0 F D E L T A s G M A p Editor . CHARLES L. FARRAR From the Desk of The Grand President . 42 Editorial Advisory Board Rhode Island Dedicates New College of Bu siness Building .. 43 Dr. H. Nicholas Windeshausen 3908 Pounds Avenue Among the Chapters ... .... ... .. ... ... .. ... · · 45 Sacramento, California 95821 Through the Eyes of an Educator 69 Timothy D. Gover 2300 Richmond Avenue With the Alumni the World Over 70 Mattoon, Illinois 61938 Firman H. -

Fall 1989 CONTENTS Icrescent DEADLINES EEMRES of GAMMA PHI BETA Winter

COMMENTARY During September, all Many other special girls have focus of the Foundation. From Gamma Phi Beta alumnae will their lives enhanced as a result your own experience in Gamma receive an annual appeal letter of Gamma Phi Beta alumnae Phi Beta you realize that much requesting a contribution for groups that apply for Founda - of the Sorority’s service to mem- the Foundation. Whether you tion supplemental grants to pro - bers is educational. Many times are a recent graduate receiving vide camperships in their own members have told me that suc- your first letter or a loyal donor, communities. Last year the cess in careers or community the Foundation needs your fi- TYustees were able to designate service or family relationships nancial support. $20,000 for local camperships is a direct result of Sorority The Gamma Phi Beta Founda- and camps. training. tion was established in 1958 as Foundation donors recognize an independent public founda- Financial Aid the value of Sorority educa- tion authorized by the United Financial aid for deserving tional programming and wel- States Internal Revenue Service Gamma Phi Betas has been a come the opportunity to expand to receive tax deductible dona- Foundation service since 1958. it through tax deductible gifts. tions. By law, Foundation funds Most financial aid is in the form This year the Foundation was can be used only for philan- of grants to collegians and able to designate $55,000 to thropic and educational pur - alumnae seeking scholarships help underwrite Leadership poses. and fellowships, which are fi- Training School and PACE pro- Each year the Foundation nanced by interest income from grams. -

The Portals New Edition Final 9Jul2017

THE PORTALS OF TAU EPSILON PHI Compiled and Edited in 1937 by Irving Klepper Tau Alpha 69 Assisted by Sidney S. Suntag Epsilon 134 Theodore S. Hecht Alpha 219 Last Revised by Timothy A. Smith Epsilon Iota 358 Published by The Tau Epsilon Phi Fraternity, Inc. National Headquarters Published October 1, 1937 Revised October 1, 1938 Revised October 1, 1941 Revised October 1, 1948 Revised October 1, 1952 Revised September 1, 1957 Revised September 1, 1961 Revised September 1, 1964 Revised January 2, 1967 Revised January 25, 1969 Revised July 30, 1972 Revised July 30, 1976 Revised September 1, 1988 Revised December 15, 1991 Revised August 1, 1992 Revised August 1, 1998 Revised January 8, 2007 Revised July 8, 2017 HE REED OF AU PSILON HI T C T E P _________ TO LIVE in the light of friendship — to judge our fellows not by their rank nor wealth but by their worth as men — to hold eternally before us the memory of those whom we have loved and lost — to hold forth in the solidarity of our brotherhood the nobility of actions which will make for the preservation of our highest and worthiest aim — and thus be true to the ideal of friendship — TO WALK in the path of chivalry — to be honor- able to all men and defend that honor — to fulfill our given pledge at all times — to be true to the precepts of knighthood and win the love and care of the women of our dreams — and thus be true to the ideal of chivalry — TO SERVE — for the love of service — to give unselfishly that which we may have to offer — to do voluntarily that which must be done — to revere God and to strive in His worship at all times — and thus be true to the ideal of service — TO PRACTICE each day friendship — chivalry — service — thus keeping true to these — the three ideals — of the founders of our fraternity — this is the Creed of Tau Epsilon Phi. -

LPH Current Chapters Institution and Greek Name.Csv

Chapter Expiration Dates as of 11.8.2019 Record Number Greek Name Institution Name Chapter Charter Expire Date 20573 Beta Psi Abilene Christian University 12/31/2019 20574 Alpha Theta Adelphi University 12/31/2019 20575 Delta Omega Adelphi University 12/31/2020 20576 Epsilon Delta Adrian College 12/31/2019 20577 Beta Theta Albion College 12/31/2019 20578 Kappa Upsilon Alcorn State Univ 12/31/2019 20579 Delta Rho Allegheny College 12/31/2019 20580 Theta Lambda Alma College 12/31/2019 20581 Delta Psi American University in the Emirates 12/31/2019 20582 Lambda Theta American University of Kuwait 12/31/2019 20583 Beta Iota Andrews University 12/31/2019 20584 Beta Sigma Angelo State University 12/31/2019 20585 Epsilon Omicron Aquinas College 12/31/2019 20586 Alpha Omega Arizona State University 12/31/2019 20588 Beta Arizona State University 12/31/2019 20591 Delta Theta Ashland University 12/31/2020 20592 Zeta Auburn University 12/31/2019 20593 Lambda Lambda Auburn University, Montgomery 12/31/2019 20595 Lambda Sigma Augsburg University 12/31/2019 20598 Beta Eta Augusta University 12/31/2019 20599 Alpha Beta Augustana University 12/31/2019 20600 Gamma Delta Aurora University 12/31/2019 20601 Epsilon Theta Azusa Pacific University 12/31/2019 20602 Lambda Delta Baldwin Wallace University 12/31/2019 20603 Lambda Kappa Ball State University 12/31/2019 20604 Mu Theta Barry University 12/31/2019 20605 Mu Eta Baylor University 12/31/2019 20606 Gamma Pi Bellarmine University 12/31/2019 20608 Zeta Zeta Bellevue University 12/31/2019 20609 Beta Chi Belmont -

26/21/4 Alumni Association Alumni Archives National Fraternity Reference Files, 1885-2009

26/21/4 Alumni Association Alumni Archives National Fraternity Reference Files, 1885-2009 Box 1: ACACIA California chapter, 1957-65 Cornell chapter, 1941, 1957, 1968 Geographical Directories, 1968 Historical, 1963-70 Illinois Alumni Chapter - correspondence, 1972 Illinois chapter - directories and programs, 1950-70 Illinois Wesleyan chapter, 1969-70 Journal articles - clippings, 1921 Kansas chapter, 1956, 1963-64 Michigan chapter, 1934 Northwestern chapter, 1970 Organizational Guidelines, 1947 Purdue chapter, 1968 Pythagorean: Acacia Fraternity Chapter Bulletin, 1965 Rushing Manual, 1940 Spirit of Excellence, Chapter Standards Program, 1984 “Sweetheart of Acacia” sheet music, 1925 Triad articles - clippings, 1966 Box 2: ALPHA CHI OMEGA The Alpha Chi Omega Experience, Booklet For Parents, n.d. California chapter - 60th Anniversary Celebration, 1969 Historical information, 1962-66 Illinois chapter - Iota Lyre, 1934-37 Michigan chapter - Tales of Theta, 1941 Northwestern chapter - Notes from the Lyre, 1934-35, 1965 Oregon chapter - Alpha Kappa Lyre, 1965 Wisconsin chapter - 152 Lendon Street, 1939-40 ALPHA CHI RHO California chapter - rushing brochure, ca. 1966 Farleigh Dickinson chapter - correspondence, 1985-92 Garnet and White articles - clippings, 1942, 1967, 1970, 1972 26/21/4 2 History, 1969, 1972 Illinois chapter - directory, 1966 Illinois chapter - evaluation, 1992 Illinois chapter - Phi Kappa News, 1929-32, 1962 Illinois chapter - rush materials, 1952-56 Purdue chapter - correspondence, 1963 Purdue chapter - White House Journal, 1966 Scholarship Manual, n.d. Song Books, 1972 Wisconsin chapter - The FI YO, 1939 Box 3: ALPHA CHI SIGMA "Alpha Chi Sigma Toast," c. 1914 California chapter - The Bear, 1927 Cornell chapter - brochure, 1963 Cornell chapter - Tau Topics, 1926-36, 1938, 1940, 1941, 1943, 1947-53 Harvard chapter - The Omnichronicle, 1931-34 Illinois chapter - WWW page, 1995 M.I.T.