World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

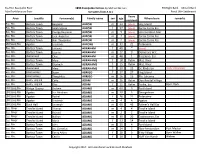

School Teachers in the Colony, 1860

Copyright 2007-8: School Teachers 1860 British Guiana Sharon Anderson in the Colony, 1860 Almanack Pg 121-123 Name of Teacher Church LAST FIRST School Locality Class Salary Alleyne John Church of Scotland All Saint's - Boys Unql. 133.33 Alsop James Church of England The Kitty II 480 Armstrong Sarah Church of England Christ Church II 320 Arthur S.E. Church of England The Craig II 400 Ashby Samuel Church of England Hackney (Pomeroon) Unql. 133.33 Bacon P.S. Church of England Plaisance, Boys I 720 Banks E.T. Church of England De Kinderen Unql. 133.33 Bean Quammy Church of England Goed Fortuin II 200 Benjamin S.W. Church of Scotland Ithaca II 400 Binning Ellen N. Church of Scotland Stanley Town Unql. 106.66 Blyden John Episcopalian Meth. Gladstoneville III 200 Bornall Elizabeth Church of England St. Philip's - Girls II 320 Brown John W. Wesleyan Mocha III 200 Callendar C.A. Church of England Louisiana III 200 Clyne A.N. Church of Scotland Vriesland III 200 Cooper Joseph B. Church of Scotland Uitvlugt I 720 Cubbison Edward A. Church of England St. George's - Boys I 720 Cumberbatch David Church of Scotland Beauvoisin III 200 Cuvilje Peter C. Wesleyan Mahaicony III 200 Dance Charles Church of England Beterverwagting II 480 Davis J.T. Wesleyan Victoria II 400 de Bakker George Wesleyan Virginia Unql. 133.33 Don Thomas Church of England Queen's Town II 400 Drew W.E. Wesleyan All Saints II 480 Eastman Emma Church of England St. George's - Girls II 320 Eburne Alex Church of England Enmore III 200 Emery Clementina Wesleyan Kingston, Girls II 320 Eversley B. -

Guyana / British Guiana Genealogy Society Surnames "M" 1898 125

Guyana / British Guiana Surnames "M" Copyright 2008: S. Anderson, Genealogy Society All Rights Reserved YR PG Last First Mid OCC Employer Address City/Area 1898 125 MacDonald James Panboiler Pln Nismes West Bank 1898 125 MacDonald William Prop, Editor Berbice Gazette New Amsterdam 1898 125 MacClean Herbert Overseer Pln DeKinderen West Coast 1898 125 Macfarlane C. B. Overseer Pln Anna Regina Essequibo 1898 125 Macfarlane G. Schoolmaster St. James The Less Kitty 1898 125 MacGill Rev. J. W. Minister St. Catherine's Berbice 1898 125 MacIntyre G. R. Clerk Colonial Bank High St 1898 125 Mackay Aeuens D. Asst Secty. Hand‐in‐Hand Bldg High St 1898 125 Ma Chan Clerk Lee‐Kang Lombard St 1898 125 Mackenzie John B. Overseer Pln Eliza & Mary Berbice 1898 125 Mackenzie E. P. Clerk Hogg Curtis Campbell La Penitence 1898 125 Mackey A. P.P. Partner Booker Bros & Co Water St Res. Brickdam 1898 125 Maclaine E. F. Hd Overseer Pln Leonora West Coast 1898 125 MacLean D. Manager Pln Highbury Berbice 1898 126 Macleod Murdoch Comm Tax Alvery District 1898 126 MacMilan J. Clerk S. Wreford & Co Strand New Amsterdam 1898 126 MacMurdoch A. Asst Cutter Caldeonian Warehse. Water St 1898 126 Maclean Chas. H. Panboiler Pln Enmore East Coast 1898 126 Macuie Rev. Robert Minister St Mary's Mahaica 1898 126 Macpherson A. Overseer Pln Providence East Bank 1898 126 Macpherson J. Panboiler Pln Vergenoegen West Coast 1898 126 Macpherson James Overseer Pln Marionville Wakenaam 1898 126 Macquarrie Chas. J. Macquarrie & CO Water St Res "Ulva" Main St 1898 126 Macquarrie & Co Wine Merch Lot 37 Water St 1898 126 Macwilliam John Overseer Pln Lusignan East Coast 1898 126 Madhoo Interpreter Immg Dept Kingston 1898 126 Mahens C. -

Guyana REGION VI Sub-Regional Land Use Plan

GUYANA LANDS AND SURVEYS COMMISSION REGION VI Sub-Regional LAND USE PLAN Andrew R. Bishop, Commissioner Guyana Lands and Surveys Commission 22 Upper Hadfield Street, Durban Backlands, Georgetown Guyana September 2004 Acknowledgements The Guyana Lands and Surveys Commission wishes to thank all Agencies, Non- Governmental Organizations, Individuals and All Stakeholders who contributed to this Region VI Sub-Regional Land Use Plan. These cannot all be listed, but in particular we recognised the Steering Committee, the Regional Democratic Council, the Neighbourhood Democratic Councils, the members of the Public in Berbice, and most importantly, the Planning Team. i Table of Contents Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................... i Table of Contents ...................................................................................................... ii Figures ...................................................................................................... v Tables ...................................................................................................... v The Planning Team ..................................................................................................... vi The Steering Committee ................................................................................................... vii Support Staff .................................................................................................... vii List of Acronyms .................................................................................................. -

1896 Essequibo Census by Michael Mcturk Area Locality Family Name

Ess Riv= Essequibo River 1896 Essequibo Census by Michael McTurk RB=Right Bank LB=Left Bank Maz Riv=Mazaruni River Surnames from A to J Penal SM= Settlement Years Area Locality Forename(s) Family name sex age Where born remarks resident Ess. Riv. Bartica Town Benjamin AARON m 33 [blank] Hog Island Ess. Riv. Bartica Town Sarah Sophia AARON f 27 [blank] Carria Carria Ess Ess. Riv. Bartica Town George Benjamin AARON m 9 [blank] Hoorooraboo Maz Ess. Riv. Bartica Town Josh. Augustus AARON m 7 [blank] Carria Carria Ess Ess. Riv. Bartica Town Wm. Theophilus AARON m 2 [blank] Carria Carria Ess LB Esseq Riv Agatas Frederick AARONS m 33 21 Potaraima Ess. Riv. Bartica Town Johanna ABRAHAM f 40 ~ [blank] Ess. Riv. Bartica Town Lazarus ABRAHAM m 27 3 Demerara W.C. Ess. Riv. Awaunaac Chas. ABRAHAM m 48 1 Bassaboo, Ess. Ess. Riv. Bartica Town Mary ABRAHAMS f 18 0y6m Maz. River Ess. Riv. Bartica Town Elizabeth ABRAHAMS f 15 0y6m Maz. River Ess. Riv. Awaunaac Mary ABRAHAMS f 30 25 De Kinderen reads "D'Kinderen" Ess. Riv. Johanna Hog I. Susan ABRIGO f 27 27 Hog Island Ess. Riv. Johanna Hog I. Theophilus ABRIGO m 16 16 Pln. Johanna Ess. Riv. Buckly Hog Isld Cuffy ADAM m 26 0y6m Den Amstel Village Ess. Riv. Buckly Hog Isld Eliza ADAM f 21 0y6m Parika, Ess Born Clark LB Esseq Riv Wolga Quarry Andrew ADAMS m 60 9 Fort Island LB Esseq Riv Agatas Jus. Abraham ADAMS m 30 5 Georgetown LB Esseq Riv Agatas Rachel ADAMS f 26 21 Potaraima LB Esseq Riv Agatas Frederick ADAMS m 4 4 Agatas LB Esseq Riv Buck Hall Jeremiah ADAMS m 60 46 Palmer's Hall Ess Ess. -

Guyana Economic Opportunities

Guyana Economic Opportunities Environmental Management Systems and Clean Production: Options for Enhancing Trade Competitiveness of Small & Medium Export Manufacturers in Guyana David Gibson Chemonics International Mark Bynoe University of Guyana Submitted by: Chemonics International Inc. To: United States Agency for International Development Georgetown, Guyana Under Contract No. 504-C-00-99-00009-00 CONTENTS Acronyms i Summary of Conclusions and Recommendations iii SECTION I Introduction I-1 SECTION II Trade Competitiveness & the Environment II-5 SECTION III Overview of SME Export Manufacturing Sectors III-9 SECTION IV Manufacturing Sectors & Exports IV-13 SECTION V Export Industry Efficiencies, Trade and Environment V-17 SECTION VI Industry Sector Selection VI-21 SECTION VII Environmental Aspects & Impacts of Fishery Operations VII-25 SECTION VIII Aspects and Impacts of Forestry VIII-33 SECTION IX Poultry, Meat and Dairy IX-39 ANNEX A Terms of Reference for the Implementation of an Environmental Survey ANNEX B Meeting Schedule ANNEX C Participants in the Gibson/Bynoe Debriefing ACRONYMS ACP Africa, Caribbean and Pacific Group BMP Best Management Practices BOD Biochemical Oxygen Demand BOG Bank of Guyana BSE Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy Caricom Caribbean Community CBH Central Board of Health CHPA Central Housing & Planning Authority CEPAA Council on Economic Priorities Accreditation Agency CIF Cost, Insurance, and Freight COD Chemical Oxygen Demand CP Clean Production CSME Caricom Single Market and Economy EEZ Exclusive Economic -

1880 British Guiana Directory Copyright 2008: S

1880 British Guiana Directory Copyright 2008: S. Anderson, All Rights Reserved YR PG Last First Mid Occupation Employer Address City/Area 1880 49 Backer J.N. L. 1st Clerk Auditor Gen. Office Georgetown 1880 49 Backer T.M. L. Superintendent Leper Asylum Mahaica 1880 49 Bagnell John Janitor Local Museum New North St 1880 49 Bagnell John Overseer Hampton Court Essequibo 1880 49 Bagot C. Clerk Sandbach,Parker & Co. Water St 1880 49 Bagot E. Aidwaiter Customs House Georgetown 1880 49 Bagot E. Pan Boiler Ruimveldt East Bank 1880 49 Bagot George Manager Annandale East Coast 1880 49 Bagot John Clerk Magistrate's Office Corentyne Coast 1880 49 Bagot John Overseer Eliza & Mary Berbice 1880 49 Bagot T. C. Manager Herstelling East Bank 1880 49 Bagot Walter Merchant Water St 1880 49 Baker A. E. Formn. Printer Baldwin & Co. Water St 1880 49 Baldini Rev. Joseph Roman Catholic Church Main St. 1880 49 Baldwin J. Y. Stationer Water St 1880 49 Ball G. Overseer Windsor Forest West Coast 1880 49 Banfield F. Asst. Master Queen's College 1880 49 Baptista Francisco Partner Baptista Bros. Water St 1880 49 Baptista J. Partner Baptista Bros. Water St 1880 49 Baptista Manoel Clerk Baptista Bros. Water St 1880 49 Barber Samuel & Co. Merchant Water St 1880 49 Barclay George Overseer Goldstone Hall Berbice 1880 49 Barclay H. Spec. Magistrate Demerara River Dist 1880 49 Barclay R. A. Overseer Versailles West Bank 1880 49 Bardan C. J. Clerk Scott & Co. Water St 1880 49 Bardan James Town Overseer Lot 38 Brickdam 1880 49 Bardon Moses Clerk Mortimer Cossou Main St. -

Message from the Vice Chancellor

Message from The Vice Chancellor Professor Ivelaw Lloyd Griffith “I was and still am that same ship which carried me to the new shore, the same vessel containing all the memories and dreams of the child in the brick house with the toy tea set. I am the shore I left behind as well as the home I return to every evening.” – Lusia A. Igloria Whether or not any Guyanese in the Diaspora grew up in brick houses or had toy tea sets, the essence of the reflections above by distinguished Filipina-American poet and scholar Luisa Aguilar Igloria is as pertinent to the realities of the Guyanese Diaspora as it is to the Filipino Diaspora, in which context it was made. Guyanese who left the shore behind, for whatever reason, generally are not just caught in the shore-home whirlpool, but often are passionate about aiding people and practices back home. Yet, quite often the passion is manifested more in platitudes, with dreaming, and less in practices, with doing. The gap between dreaming and doing often derives from insufficient institutional facilitation of the shore-home engagement. This is a Guyana reality, as it is one in many other places. This conference—and the Centre to be established—reflect our University’s willingness to help address the shore-home engagement gap, to help enable our nation to move beyond Dreaming Diaspora Engagement to Doing Diaspora Engagement, and to do so mindful of our racial, political, demographic, and socio-economic realities at home and abroad. Welcome, then, to DEC 2017—this historic Dreaming and Doing Engagement Experience! I encourage you to make full use of the opportunities offered this week. -

1896 Essequibo Census by Michael Mcturk Area Locality Family Name

Ess Riv= Essequibo River 1896 Essequibo Census by Michael McTurk RB= Right Bank LB=Left Bank Maz Riv=Mazaruni River J to Z Hog I= Hog Island Penal SM=Settlement Years Area Locality Forename(s) Family name sex age Where born remarks resident Ess. Riv. Bartica Town Janukie JANUKIE m 26 1 India One name only R.B. Ess Riv Foulmouth Ant. Gomes JARDINE m 16 ~ Madeira : names v unclear. Ess. Riv. Bartica Town Carolina JARDINE f 75 0y7m Madeira Widow b. Pei Ess. Riv. Bartica Town Thomas JARVIS m 24 5 Georgetown Mazaruni Penal SM Amelia JARVIS f 22 1 B. Guiana Ess. Riv. Bartica Town Frans Faria JASMIN m 27 5 Madeira RB Esseq Riv Dalli Quarry William JASON m 9 9 Cassoeni Ess Riv RB Esseq Riv Dalli Quarry Thomas JASON m 40 12 Sarepapa Ess Riv RB Esseq Riv Dalli Quarry Ellen JASON f 24 7 Mahaica Born Van der Kay Ess. Riv. Bartica Town Frances JAY f 40 40 Carria Carria . Ess Born Andries Ess. Riv. Bartica Town Joseph JAY m 21 21 Fort Island Ess. Riv. Bartica Town Theophilus JAY m 16 16 Fort Island Ess. Riv. Bartica Town Susan JAY f 18 18 Fort Island Ess. Riv. "Swart Hook" Jaypaul JAYPAUL m 30 1 Anay, Ind. One name only LB Esseq Riv Wallaba James JEFFREY m 53 32 Supenaam LB Esseq Riv Wallaba Elizth. JEFFREY f 52 52 Wallaba Born Norden LB Esseq Riv Wallaba James JEFFREY m 28 28 Wallaba LB Esseq Riv Wallaba George JEFFREY m 25 25 Wallaba LB Esseq Riv Wallaba John JEFFREY m 21 21 Wallaba LB Esseq Riv Wallaba Mary JEFFREY f 18 18 Wallaba LB Esseq Riv Caria-caria Kinion JEFFREY m 50 ~ Supenaam Ess. -

The Mineral Industry of Guyana in 2015

2015 Minerals Yearbook GUYANA [ADVANCE RELEASE] U.S. Department of the Interior May 2019 U.S. Geological Survey The Mineral Industry of Guyana By Philip A. Szczesniak A significant offshore crude petroleum discovery by Exxon 18.5% compared with that of 2014. The increases in gold and Mobil Corp. of the United States in May 2015 could provide a diamond production were attributed to a boost in the output of boost to the economy of Guyana during the next several years medium- and large-scale mines. Preliminary data for bauxite and stimulate mineral fuel exploration and investment. With indicate that production decreased by about 6.4% compared an economy measured at about $3 billion, this crude petroleum with that of 2014 to about 1.5 million metric tons (Mt). Crushed discovery and potential development could add billions of stone production decreased by 56% owing to a decrease in dollars to the economy during the next decade. In 2015, there construction activity (table 1; Bank of Guyana, 2016, p. 10–12). was no production of mineral fuels in Guyana, but there was some production of metals and industrial minerals, including Structure of the Mineral Industry bauxite, diamond, gold, loam, and crushed stone. According Table 2 is a list of the major mineral industry facilities to the Guyana Geology and Mines Commission (GGMC), the in Guyana. country has occurrences of other minerals, such as chromite, copper, iron ore, mica, peat, phosphate, platinum-group metals, Mineral Trade quartz, rare earths, tin, and others (table 1; Guyana Geology and Mines Commission, 2014a–c; WorldOil.com, 2015; Bank of The value of Guyana’s exports was unchanged from that Guyana, 2016, p. -

Estimates of the Public Sector

GUYANA ESTIMATES OF THE PUBLIC SECTOR, CENTRAL GOVERNMENT DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME CAPITAL PROJECTS PROFILES- For the year 20 1 0 As presented to THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY VOLUME 3 GUYANA CENTRAL GOVERNMENT DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME CAPITAL PROJECTS PROFILES For the year as presented to THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY VOLUME 3 SECTION 1 CENTRAL GOVERNMENT CAPITAL PROJECT PROFILES BY AGENCY TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION I - CENTRAL GOVERNMENT CAPITAL PROJECT PROFILES BY AGENCY INDEX TO CENTRAL GOVERNMENT CAPITAL PROJECTS DIVISION AGENCYPROGRAMME PROJECT TITLE REF. # 1 OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT 011 - Head Office Administration Office and Residence of the President 1 1 OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT 011 - Head Office Administration Information Communication Technology 2 1 OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT 011 - Head Office Administration Minor Works 3 1 OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT 011 - Head Office Administration Land Transport 4 1 OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT 011 - Head Office Administration Purchase of Equipment 5 1 OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT 011 - Head Office Administration Integrity Commission 6 1 OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT 011 - Head Office Administration Lands and Surveys 7 1 OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT 011 - Head Office Administration Land Use Master Plan 8 1 OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT 011 - Head Office Administration Guyana Office for Investment 9 1 OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT 011 - Head Office Administration Environmental Protection Agency 10 1 OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT 011 - Head Office Administration National Parks Commission 11 1 OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT 011 - Head Office Administration Government -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. SUMMAR y ......................................................................... ··-.:::::=.::::,:,:;;;r- 2. THE GEOLOGICAL SERVICES DIVISION ............................................. 5 2:1 The Bauxite Sampling Programme ....................................................5 2:2 The ·upper Waini ................................................... .....................6 2:3 Coverden Clays ................... �: ......................................................6 2:4 National Rainforest Project .............................................................6 2: 5 Concluding Remarks .................................................................... 7 2:6 Activities of Foreign Mining Companies ............................................ 7 3. MINES DEVELOPMENT ANDPRODUCTION DIVISIONS . .. .. .. .. .. 11 3:1 Mineral Processing Unit ................................................................11 3:2 Mining Inspectorat� .....................................................................13 3:2:1 Mining Stations .................. ·. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 13 3:2:2 Visits .......................................................... .............................· 13 3:2:3 Inspectors Tour - Bauxite Industry ................................................... 13 3:2:4 Inspection Tour - Quarry Mining .....................................................14 3:2:5 Protection of Environment .............................................................14 3:2:6 Mining Studies ..................................................................14 -

1882 BG Directory ‐ "A" Surnames

Copyright 2008: S. Anderson 1882 BG Directory ‐ "A" Surnames Year Page Last First Mid Occupation Employer Address City/Area 1882 50 Backer T.M. L. Supt Leper Asylum Mahaica 1882 50 Backer W.H. L. Compositor Middle St 1882 50 Baggot John Snr. Overseer Eliza & Mary Berbice 1882 50 Bagnell John Janitor Colonial Museum Water St 1882 50 Bagot C. Clerk Sandbach Parker & Co Water St 1882 50 Bagot E. Panboiler Ruimveld Demerara 1882 50 Bagot E. Aid Waiter Custom House Georgetown 1882 50 Bagot Geo. Manager Annandale Demerara East Coast 1882 50 Bagot John Clerk Magistrate's Office Corentyne 1882 50 Bagot T. C. Clerk Demerara Wood Work Co Charlestown 1882 50 Bagot Walter Merchant 25 Water St 1882 50 Baker A. E. Compositor Foreman, Baldwin & Co 1882 50 Bakht Pradhee Catechist Bladenhall Demerara East Coast 1882 50 Baldini Rev. Jos. R.C. Church Main St 1882 50 Baldwin & Co. Booksellers Water St 1882 50 Baldwin John Sole Partner Baldwin & Co Water St 1882 50 Banhos F. H. Clerk Park & Cunningham Water St 1882 51 Barber & Co Samuel Merchant Water St 1882 51 Barclay Herbert Spec. Magistrate Demerara River 1882 51 Barclay J. A. Clerk A.W. Perot & Co Water St 1882 51 Barclay R. A. Overseer Versailles Demerara 1882 51 Barden James Nuisance Inspect. 58 Brickdam 1882 51 Barnard H. H. Manager Mara East Bank Berbice 1882 51 Barnes C. P. Clerk Booker Bros & Co Water St 1882 51 Barnes E. J. Cashier BG Bank Water St 1882 51 Barnes J. Schoolmaster Organist, St Michael' s Berbice 1882 51 Barnes O.