'All of a Sudden, It's Becoming Toronto': Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CERTIFICATE of APPROVAL 11160 Woodbine Avenue Limited 15

CONTENT COPY OF ORIGINAL Ministry of the Environment Ministère de l’Environnement CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL MUNICIPAL AND PRIVATE SEWAGE WORKS NUMBER 0665-8GZMH6 Issue Date: May 24, 2011 11160 Woodbine Avenue Limited 15 Gormley Industrial Avenue, Unit 3, Box 215 Gormley, Ontario L0H 1G0 Site Location: Lot Part of 28, Concession 3 Town of Markham, Regional Municipality of York, Ontario You have applied in accordance with Section 53 of the Ontario Water Resources Act for approval of: storm sewersto be constructed in the Town of Markham, in the Regional Municipality of York, on Easement (from north of Woodbine Bypass to east of Honda Boulevard); all in accordance with the application from 11160 Woodbine Avenue Limited, dated February 16, 2011, including final plans and specifications prepared by Masongsong Associates Engineering Limited. In accordance with Section 100 of the Ontario Water Resources Act, R.S.O. 1990, Chapter 0.40, as amended, you may by written notice served upon me and the Environmental Review Tribunal within 15 days after receipt of this Notice, require a hearing by the Tribunal. Section 101 of the Ontario Water Resources Act, R.S.O. 1990, Chapter 0.40, provides that the Notice requiring the hearing shall state: 1. The portions of the approval or each term or condition in the approval in respect of which the hearing is required, and; 2. The grounds on which you intend to rely at the hearing in relation to each portion appealed. The Notice should also include: 3. The name of the appellant; 4. The address of the appellant; 5. -

City of Toronto — Detached Homes Average Price by Percentage Increase: January to June 2016

City of Toronto — Detached Homes Average price by percentage increase: January to June 2016 C06 – $1,282,135 C14 – $2,018,060 1,624,017 C15 698,807 $1,649,510 972,204 869,656 754,043 630,542 672,659 1,968,769 1,821,777 781,811 816,344 3,412,579 763,874 $691,205 668,229 1,758,205 $1,698,897 812,608 *C02 $2,122,558 1,229,047 $890,879 1,149,451 1,408,198 *C01 1,085,243 1,262,133 1,116,339 $1,423,843 E06 788,941 803,251 Less than 10% 10% - 19.9% 20% & Above * 1,716,792 * 2,869,584 * 1,775,091 *W01 13.0% *C01 17.9% E01 12.9% W02 13.1% *C02 15.2% E02 20.0% W03 18.7% C03 13.6% E03 15.2% W04 19.9% C04 13.8% E04 13.5% W05 18.3% C06 26.9% E05 18.7% W06 11.1% C07 29.2% E06 8.9% W07 18.0% *C08 29.2% E07 10.4% W08 10.9% *C09 11.4% E08 7.7% W09 6.1% *C10 25.9% E09 16.2% W10 18.2% *C11 7.9% E10 20.1% C12 18.2% E11 12.4% C13 36.4% C14 26.4% C15 31.8% Compared to January to June 2015 Source: RE/MAX Hallmark, Toronto Real Estate Board Market Watch *Districts that recorded less than 100 sales were discounted to prevent the reporting of statistical anomalies R City of Toronto — Neighbourhoods by TREB District WEST W01 High Park, South Parkdale, Swansea, Roncesvalles Village W02 Bloor West Village, Baby Point, The Junction, High Park North W05 W03 Keelesdale, Eglinton West, Rockcliffe-Smythe, Weston-Pellam Park, Corso Italia W10 W04 York, Glen Park, Amesbury (Brookhaven), Pelmo Park – Humberlea, Weston, Fairbank (Briar Hill-Belgravia), Maple Leaf, Mount Dennis W05 Downsview, Humber Summit, Humbermede (Emery), Jane and Finch W09 W04 (Black Creek/Glenfield-Jane -

Disrupting Toronto's Urban Space Through the Creative (In)Terventions

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Institutional Repository of the Ibero-American Institute, Berlin Disrupting Toronto’s Urban Space through the Creative (In)terventions of Robert Houle Alterando el espacio urbano de Toronto a través de las (in)tervenciones creativas de Robert Houle Julie Nagam University of Winnipeg and Winnipeg Art Gallery, Canada [email protected] Abstract: is essay addresses the concealed geographies of Indigenous histories in the City of Toronto, Canada, through selected artworks that address history, space, and place. e research is grounded in the idea that the selected artworks narrate Indigenous stories of place to visually demonstrate an alternative cartography that challenges myths of settlement situated in the colonial narratives of archaeology and geography. Indigenous artist Robert Houle has created artworks that narrate Indigenous stories of place using the memories and wisdom of Indigenous people in areas of art, archaeology, and geography (land). is visual map is grounded in the premise that the history of the land is embodied in Indigenous knowledge of concealed geographies and oral histories. It relies upon concepts of Native space and place to demonstrate the signicance of the embodied knowledges of Indigenous people and highlights the importance of reading the land as a valuable archive of memory and history. Keywords: Indigenous; art; geographies; space; urban; Toronto; Canada; 20th-21st centuries. Resumen: Este ensayo aborda las geografías ocultas de las historias indígenas en la ciudad de Toronto, Canadá, a través de obras de arte seleccionadas que abordan la historia, el espacio y el lugar. La investigación se basa en la idea de que las obras seleccionadas narran historias de lugar indígenas para mostrar visualmente una cartografía alternativa que desafía los mitos de asentamiento situados en las narrativas coloniales de la arqueología y la geografía. -

908 Queen Street East

Corner Retail For Lease 908 Queen Street East Overview Located in Leslieville, one of Toronto’s most desirable neighborhoods, 908 Queen Street East offers an opportunity to secure a high-exposure retail location on the northeast corner of Queen Street East & Logan Avenue. Boasting excellent walk scores, a TTC stop at front floor, and patio potential, this location is suitable for a variety of retail uses. With Leslieville’s trendy restaurants and coffee shops, eclectic local merchants, convenient transit options, and new residential developments, the area has experienced substantial growth and has become a destination for visitors. Demographics 0.5km 1km 1.5km Population 8,412 25,722 47,403 Daytime Population 7,783 21,861 40,326 Avg. Household Income $119,523 $117,100 $113,722 Median Age 39 39 39 Source: Statistics Canada, 2020 Property Details GROUND FLOOR | 1,644 SF AVAILABLE | Immediately TERM | 5 - 10 Years NET RENT | Please contact Listing Agents ADDITIONAL RENT | $20.50 PSF (est. 2020) Highlights • “Right sized” corner retail space • Excellent frontage on Queen Street East and Logan Avenue • Patio potential • 501 Queen & 503 Kingston Streetcars stop at front door • Neighborhood co-tenants include: Starbucks, Nutbar, A&W, Freshii, rowefarms, Circle K and more Neighbouring Retail McLeary Playground MCGEE STREET Real Estate Homeward Brokerage 807A Residential 811-807 Wholesome Pharmacy 811A Residential 813 Jimmie SimpsonPark Residential 815 K.L. Coin Co 817A Residential 819-817 Baird MacGregor Insurance Brokers 825 EMPIRE AVENUE Woodgreen -

(Between Woodbine Avenue and Nursewood Road) – Restaurant Study – Final Report

STAFF REPORT ACTION REQUIRED Queen Street East (between Woodbine Avenue and Nursewood Road) – Restaurant Study – Final Report Date: March 17, 2017 To: Toronto and East York Community Council From: Director, Community Planning, Toronto and East York District Wards: Ward 32 – Beaches-East York Reference 16 103072 SPS 00 OZ Number: SUMMARY This proposal is to amend the Zoning By-law to update the regulations respecting restaurants and related uses on Queen Street East between the east side of Woodbine Avenue and the west side of Nursewood Road in Ward 32. Staff are recommending a number of amendments to the Zoning By-law which seek to balance the concerns of the residents and the business/property owners. The cumulative effects of the amendments aim to continue to limit the overall impacts of restaurants and related uses on adjacent residential areas, while improving options and allowing opportunities for new restaurants and related uses to open and prosper. This report reviews and recommends approval of amendments to the Zoning Bylaw. RECOMMENDATIONS The City Planning Division recommends that: 1. City Council amend Zoning By-law 438-86, as amended, substantially in accordance with the draft Zoning By- law Amendment attached as Attachment No. 3. Staff report for action – Final Report – Queen Street East (between Woodbine Avenue and Nursewood Road) Restaurant Study 1 2. City Council authorize the City Solicitor to make such stylistic and technical changes to the draft Zoning By-law Amendment as may be required. Financial Impact The recommendations in this report have no financial impact. ISSUE BACKGROUND In 1985, a City Planning report entitled "Queen Street East Licensed Eating Establishment Study" went to Council with recommendations on zoning standards for restaurants. -

Victoria Park to Woodbine Avenue 08-20-14

Construction Schedule: Danforth Avenue - Woodbine Avenue to Victora Park ( June 9, 2014 to November 27, 2014 ) The City of Toronto has scheduled watermain and sewer replacement, road and sidewalk work and streetscaping improvements on Danforth Avenue between Woodbine Avenue and Victoria Park Avenue. Important Note: Danforth Village BIA timelines provided are contingent on contractor's schedule, weather and other unforeseen events. November 3 to 7 November 7 to 18 N October 20 to 31 October 6 to 17 September 22 to October 3 October 24 to November 14 November 1 to 27 July 14 to September 15 Main Square June 9 to September 15 August 25 to Late October July 28 to August 25 August 25 to September 5 September 8 to 19 September 29 to October 24 September 2 to 26 June 9 to September 15 September 17 to October 6 July 28 to Late October * Striped Areas Indicate Active Construction Zones* LEGEND Construction Hours Questions? Contact : Danforth Village Business Improvement Area Monday to Friday - 7am to 7pm Fred Meco Sidewalk Repairs & Streetscaping (Arrow indicates direction of construction) - July 28 to November 27 Some evening and weekend work may be required. Project Engineer - Woodbine Ave. to Dawes Rd. Road Resurfacing (Arrow indicates direction of construction) - November 3 to 7 416-397-4591 [email protected] Expect During Construction Watermain Replacement, Sidewalk Repairs and Road Resurfacing - June 9 to September 15 Mario Goolsarran Project Engineer - Dawes Rd. to Victoria Park Watermain Replacement, Sidewalk Repairs and Road Resurfacing - June 9 to September 15 • Limited on-street parking in some areas • Vehicle access to driveways may be temporarily 416-392-9187 [email protected] Sewer Replacement, Watermain Replacement, Sidewalk Repairs and Road Resurfacing - August 25 to Late October restricted • Noise, dust, some vibration www.toronto.ca/danforth Watermain Replacement - July 14 to September 15 Sewer Replacement, Road Reconstuction - July 28 to Late October Pedestrian access to local businesses and walkways will be maintained at all times. -

1881 Queen Street East

Corner Retail For Lease 1881 Queen Street East Overview Located in the Beaches, one of Toronto’s most desirable neighbourhood’s in the city’s east end, 1881 Queen Street East offers an opportunity to secure a high exposure retail location on the southeast corner of Queen Street East & Woodbine Avenue. Boasting excellent walk scores, prominent frontage, and a TTC stop at front doo, this opportunity is suitable for a variety of retail uses. With the Beaches’ trendy restaurants and coffee shops, local and national retailers, convenient transit options, and new residential developments, the area has experienced substantial growth and has become a destination for visitors. Demographics 1km 2km 3km Population 18,711 61,021 132,354 Daytime Population 15,003 42,054 96,333 Avg. Household Income $160,232 $136,737 $122,108 Median Age 42 41 41 Source: Statistics Canada, 2020 Property Details GROUND FLOOR | 2,281 SF AVAILABLE | Immediately TERM | 5 - 10 years NET RENT | Please contact Listing Agents ADDITIONAL RENT | $15.00 PSF (est. 2020) Highlights • “Right sized” corner retail space • Space is divisible to 1,413 SF & 868 SF • Excellent frontage on Queen Street East and Woodbine Avenue • 501 Queen & 503 Kingston Streetcars stop at front door • Neighborhood co-tenants include: Bruno’s Fine Food’s, LCBO, Structube, Wine Rack, and many more pcv N Neighbouring Retail & Developments 1630 Queen St. East 1880 Queen St. East Marlin Spring Developments, The Riedel Group Altree Developments 31 Units 88 Units Completed (2018) A Construction (2020) C A B C D 1684 Queen St. East 1884 Queen St. -

142 Downtown/Avenue Rd Express

Toronto Transit Commission Express bus services November 2009 The TTC operates express or limited-stop rocket services on 25 bus routes. All 143 DOWNTOWN/BEACH EXPRESS of the services operate during the peak periods from Monday to Friday, and 143 Downtown-Neville Park some of the services also operate at off-peak times. Five of the routes are Monday to Friday peak period premium-fare express service between the Beach premium-fare Downtown Express routes; customers travelling on these routes and downtown. pay a premium fare which is approximately double the regular TTC fare. All Westbound: Buses serve all stops between Neville Park Loop and Woodbine other express and rocket routes charge regular TTC fares. For more information, Avenue, and then stop only downtown at all stops on Richmond Street and refer to the TTC Ride Guide map, the TTC web page at www.ttc.ca, or call Adelaide Street. In the afternoon, westbound buses stop only at Neville Park 416-393-INFO (416-393-4636). Loop and downtown. Eastbound: Buses serve all stops downtown on Richmond Street and Adelaide 192 AIRPORT ROCKET Street, and then stop only on Queen Street at all stops east of Woodbine 192 Kipling Stn-Pearson Airport Avenue. Express service all day every day between Kipling Station and Pearson Airport. Buses stop at Kipling Station, Dundas & East Mall Crescent, Terminal 1 (Ground 144 DOWNTOWN/DON VALLEY EXPRESS level), Terminal 3 (Arrivals level), and Jetliner Road/Airport Road only. 144 Downtown-Wynford and Underhill 144A Underhill-Downtown 142 DOWNTOWN/AVENUE RD EXPRESS 144B Wynford-Downtown Monday to Friday peak period premium-fare express service between Underhill 142 Downtown-Highway 401 Monday to Friday peak period premium-fare express service between Avenue Drive, Wynford Heights, and downtown. -

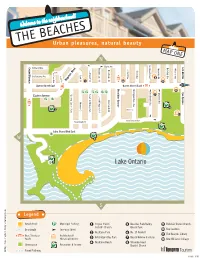

90Ab-The-Beaches-Route-Map.Pdf

THE BEACHESUrban pleasures, natural beauty MAP ONE N Kenilworth Ave Lee Avenue Coxw Dixon Ave Bell Brookmount Rd Wheeler Ave Wheeler Waverley Rd Waverley Ashland Ave Herbert Ave Boardwalk Dr Lockwood Rd Elmer Ave efair Ave efair O r c h ell A ell a r d Lark St Park Blvd Penny Ln venu Battenberg Ave 8 ingston Road K e 1 6 9 Queen Street East Queen Street East Woodbine Avenue 11 Kenilworth Ave Lee Avenue Kippendavie Ave Kippendavie Ave Waverley Rd Waverley Sarah Ashbridge Ave Northen Dancer Blvd Eastern Avenue Joseph Duggan Rd 7 Boardwalk Dr Winners Cir 10 2 Buller Ave V 12 Boardwalk Dr Kew Beach Ave Al 5 Lake Shore Blvd East W 4 3 Lake Ontario S .com _ gd Legend n: www.ns Beach Front Municipal Parking Corpus Christi Beaches Park/Balmy Bellefair United Church g 1 5 9 Catholic Church Beach Park 10 Kew Gardens . Desi Boardwalk One-way Street d 2 Woodbine Park 6 No. 17 Firehall her 11 The Beaches Library p Bus, Streetcar Architectural/ he Ashbridge’s Bay Park Beach Hebrew Institute S 3 7 Route Historical Interest 12 Kew Williams Cottage 4 Woodbine Beach 8 Waverley Road : Diana Greenspace Recreation & Leisure g Baptist Church Writin Paved Pathway BEACH_0106 THE BEACHESUrban pleasures, natural beauty MAP TWO N H W Victoria Park Avenue Nevi a S ineva m Spruc ca Lee Avenue Kin b Wheeler Ave Wheeler Balsam Ave ly ll rbo Beech Ave Willow Ave Av Ave e P e Crown Park Rd gs Gle e Hill e r Isleworth Ave w o ark ark ug n Manor Dr o o d R d h R h Rd Apricot Ln Ed Evans Ln Blvd Duart Park Rd d d d 15 16 18 Queen Street East 11 19 Balsam Ave Beech Ave Willow Ave Leuty Ave Nevi Hammersmith Ave Hammersmith Ave Scarboro Beach Blvd Maclean Ave N Lee Avenue Wineva Ave Glen Manor Dr Silver Birch Ave Munro Park Ave u Avion Ave Hazel Ave r sew ll Fernwood Park Ave Balmy Ave e P 20 ood R ark ark Bonfield Ave Blvd d 0 Park Ave Glenfern Ave Violet Ave Selwood Ave Fir Ave 17 12 Hubbard Blvd Silver Birch Ave Alfresco Lawn 14 13 E Lake Ontario S .com _ gd Legend n: www.ns Beach Front Municipal Parking g 13 Leuty Lifesaving Station 17 Balmy Beach Club . -

York Region Heritage Directory Resources and Contacts 2011 Edition

York Region Heritage Directory Resources and Contacts 2011 edition The Regional Municipality of York 17250 Yonge Street Newmarket, ON L3Y 6Z1 Tel: (905)830-4444 Fax: (905)895-3031 Internet: http://www.york.ca Disclaimer This directory was compiled using information provided by the contacted organization, and is provided for reference and convenience. The Region makes no guarantees or warranties as to the accuracy of the information. Additions and Corrections If you would like to correct or add information to future editions of this document, please contact the Supervisor, Corporate Records & Information, Office of the Regional Clerk, Regional Municipality of York or by phone at (905)830-4444 or toll- free 1-877-464-9675. A great debt of thanks is owed for this edition to Lindsay Moffatt, Research Assistant. 2 Table of Contents Page No. RESOURCES BY TYPE Archives ……………………………………………………………..… 5 Historical/Heritage Societies ……………………………… 10 Libraries ……………………………………………………………… 17 Museums ………………………………………………………………21 RESOURCES BY LOCATION Aurora …………………………………………………………………. 26 East Gwillimbury ………………………………………………… 28 Georgina …………………………………………………………….. 30 King …………………………………………………………………….. 31 Markham …………………………………………………………….. 34 Newmarket …………………………………………………………. 37 Richmond Hill ……………………………………………………… 40 Vaughan …………………………………………………………….. 42 Whitchurch-Stouffville ……………………………………….. 46 PIONEER CEMETERIES ………..…………..………………….. 47 Listed alphabetically by Local Municipality. RESOURCES OUTSIDE YORK REGION …………….…… 62 HELPFUL WEBSITES ……………………………………………… 64 INDEX…………………………………………………………………….. 66 3 4 ARCHIVES Canadian Quaker Archives at Pickering College Website: http://www.pickeringcollege.on.ca Email: [email protected] Phone: 905-895-1700 Address: 16945 Bayview Ave., Newmarket, ON, L3Y 4X2 Description: The Canadian Quaker Archives of the Canadian Yearly Meetings of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) is housed at Pickering College in Newmarket. The records of Friends’ Monthly and Yearly Meetings in Canada are housed here. -

923466Magazine1final

www.globalvillagefestival.ca Global Village Festival 2015 Publisher: Silk Road Publishing Founder: Steve Moghadam General Manager: Elly Achack Production Manager: Bahareh Nouri Team: Mike Mahmoudian, Sheri Chahidi, Parviz Achak, Eva Okati, Alexander Fairlie Jennifer Berry, Tony Berry Phone: 416-500-0007 Email: offi[email protected] Web: www.GlobalVillageFestival.ca Front Cover Photo Credit: © Kone | Dreamstime.com - Toronto Skyline At Night Photo Contents 08 Greater Toronto Area 49 Recreation in Toronto 78 Toronto sports 11 History of Toronto 51 Transportation in Toronto 88 List of sports teams in Toronto 16 Municipal government of Toronto 56 Public transportation in Toronto 90 List of museums in Toronto 19 Geography of Toronto 58 Economy of Toronto 92 Hotels in Toronto 22 History of neighbourhoods in Toronto 61 Toronto Purchase 94 List of neighbourhoods in Toronto 26 Demographics of Toronto 62 Public services in Toronto 97 List of Toronto parks 31 Architecture of Toronto 63 Lake Ontario 99 List of shopping malls in Toronto 36 Culture in Toronto 67 York, Upper Canada 42 Tourism in Toronto 71 Sister cities of Toronto 45 Education in Toronto 73 Annual events in Toronto 48 Health in Toronto 74 Media in Toronto 3 www.globalvillagefestival.ca The Hon. Yonah Martin SENATE SÉNAT L’hon Yonah Martin CANADA August 2015 The Senate of Canada Le Sénat du Canada Ottawa, Ontario Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A4 K1A 0A4 August 8, 2015 Greetings from the Honourable Yonah Martin Greetings from Senator Victor Oh On behalf of the Senate of Canada, sincere greetings to all of the organizers and participants of the I am pleased to extend my warmest greetings to everyone attending the 2015 North York 2015 North York Festival. -

Performance Assessment of the Eastern Beaches Detention Tank - Toronto, Ontario

Performance Assessment of the Toronto Eastern Beaches Detention Tank - Toronto, Ontario 2004 PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT OF THE EASTERN BEACHES DETENTION TANK - TORONTO, ONTARIO a report prepared by the STORMWATER ASSESSMENT MONITORING AND PERFORMANCE (SWAMP) PROGRAM for Great Lakes Sustainability Fund Ontario Ministry of the Environment Toronto and Region Conservation Authority Municipal Engineers Association of Ontario City of Toronto July, 2004 © Toronto and Region Conservation Authority Performance Assessment of the Toronto Eastern Beaches Detention Tank NOTICE The contents of this report are the product of the SWAMP program and do not necessarily represent the policies of the supporting agencies. Although every reasonable effort has been made to ensure the integrity of the report, the supporting agencies do not make any warranty or representation, expressed or implied, with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained herein. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation of those products. No financial support was received from developers, manufacturers or suppliers of technologies used or evaluated in this project. An earlier version of this report and various memoranda on specific technical issues related to this project were prepared by SWAMP. Additional data analysis and interpretation, probabilistic modeling and report editing/writing were undertaken by Lijing Xu and Barry J. Adams from the University of Toronto’s Department of Civil Engineering under contract to the SWAMP program, as represented by the City of Toronto. PUBLICATION INFORMATION Documents in this series are available from the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority: Tim Van Seters Water Quality and Monitoring Supervisor Toronto and Region Conservation Authority 5 Shoreham Drive, Downsview, Ontario M3N 1S4 Tel: 416-661-6600, Ext.