Talking Pop-Ups Seriously: the Jurisprudence of the Infield Fly Rule

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chicago White Sox James Pokrywczynski Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette College of Communication Faculty Research and Communication, College of Publications 1-1-2011 Chicago White Sox James Pokrywczynski Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. "Chicago White Sox," in Encyclopedia of Sports Management and Marketing. Eds. Linda E. Swayne and Mark Dodds. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2011: 213-214. Publisher Link. © 2011 Sage Publications. Used with permission. Chicago White Sox 213 Chicago White Sox The Chicago White Sox professional baseball fran- chise has constantly battled for respect and attention since arriving in Chicago in 1901. Some of the lack of respect has been self-inflicted, coming from stunts such as uniforms with short pants, or a disco record demolition promotion that resulted in a forfeiture of a ballgame, one of the few in baseball history. The other source of disrespect comes from being in the same market with the Chicago Cubs, which has devel- oped an elite and special image in the minds of many despite having the longest championship drought in professional sports history. The past 20 years have featured an uptick in the franchise’s reputation, with the opening of a new ballpark (called U.S. Cellular Field since 2003) that seats 40,000 plus, and a World Series championship in 2005. The franchise began in 1901 when Charles Comiskey moved his team, the St. Paul Saints, to Chicago to compete in a larger market. Comiskey soon built a ballpark on the south side of town, named it after himself, and won two champion- ships, the last under his ownership in 1917. -

Banner MAXX# * Daconil® - Heritage® - Medallion® * Subdue Makkm

Banner MAXX# * Daconil® - Heritage® - Medallion® * Subdue MAKKm Whether you are a professional golfer or a professional golf course superintendent, average doesn't cut it. You want to be the best. That's why superintendents across the country choose the premium control of Syngenta fungicides. Banner MAXXf Daconil? Heritage,® Medallion,® and Subdue MAXX® have made us the number one choice for disease Important: Always read and follow label instructions before buying or using these products. ©2005 Syngenta. Syngenta Professional Products, Greensboro, NC 27419. BannerMAXX? Daconil,® Heritage,® Medallion,® SubdueMAXX,® and the Syngenta logo are trademarks of a Syngenta Group Company. 4 protection. When it comes to the appearance of your course, par isn't good enough. Elevate your game with Syngenta. To learn more, call the Syngenta Customer Resource syngenta Center at 1-866-SYNGENTA or visit us at www.syngentaprofessionalproducts.com. Reckless Op? Accessory City The push to increase green speed hasn't More superintendents seek sleek add-ons slowed down, which could mean there's an for greens mowers to improve cutting accident waiting to happen. and overall performance. By Thomas Skernivitz By Pete Blais Prevent Defense The best way to control dollar spot on greens is to not let it surface in the first place, technical experts say. By Larry Aylward Real-Life Solutions Poa Shakedown A Healthy Injection Clemson professor Bert McCarty offers 10 tips on how to disarm annual bluegrass. for the Greens — By Thomas Skernivitz and the... Machine uses a high-speed, water-based system that's dramatically changing the way superinten- dents handle routine aeration. -

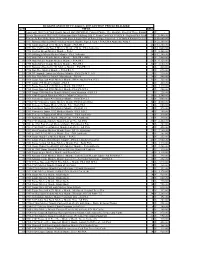

PDF of August 17 Results

HUGGINS AND SCOTT'S August 3, 2017 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED LOT# TITLE BIDS 1 Landmark 1888 New York Giants Joseph Hall IMPERIAL Cabinet Photo - The Absolute Finest of Three Known Examples6 $ [reserve - not met] 2 Newly Discovered 1887 N693 Kalamazoo Bats Pittsburg B.B.C. Team Card PSA VG-EX 4 - Highest PSA Graded &20 One$ 26,400.00of Only Four Known Examples! 3 Extremely Rare Babe Ruth 1939-1943 Signed Sepia Hall of Fame Plaque Postcard - 1 of Only 4 Known! [reserve met]7 $ 60,000.00 4 1951 Bowman Baseball #253 Mickey Mantle Rookie Signed Card – PSA/DNA Authentic Auto 9 57 $ 22,200.00 5 1952 Topps Baseball #311 Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 40 $ 12,300.00 6 1952 Star-Cal Decals Type I Mickey Mantle #70-G - PSA Authentic 33 $ 11,640.00 7 1952 Tip Top Bread Mickey Mantle - PSA 1 28 $ 8,400.00 8 1953-54 Briggs Meats Mickey Mantle - PSA Authentic 24 $ 12,300.00 9 1953 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 (MK) 29 $ 3,480.00 10 1954 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 58 $ 9,120.00 11 1955 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 20 $ 3,600.00 12 1952 Bowman Baseball #101 Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 6 $ 480.00 13 1954 Dan Dee Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 15 $ 690.00 14 1954 NY Journal-American Mickey Mantle - PSA EX-MT+ 6.5 19 $ 930.00 15 1958 Yoo-Hoo Mickey Mantle Matchbook - PSA 4 18 $ 840.00 16 1956 Topps Baseball #135 Mickey Mantle (White Back) PSA VG 3 11 $ 360.00 17 1957 Topps #95 Mickey Mantle - PSA 5 6 $ 420.00 18 1958 Topps Baseball #150 Mickey Mantle PSA NM 7 19 $ 1,140.00 19 1968 Topps Baseball #280 Mickey Mantle PSA EX-MT -

Here's to a Good and Hearty Laugh

Pin High • EDITOR'S COMMENTARY his column is just what the happy-go-lucky Mike Veeck wanted — more ink to pro- Here's to a Good mote his wacky ways. Forgive me, but I've succumbed to Veeck's media magnetism. But and Hearty Laugh TI make no apologies for this column because Veeck is worth writing about. BY LARRY AYLWARD Veeck spoke in December at the Ohio Turf Federations annual conference in Columbus, Veeck's point was that while we say we aren't Ohio. While Veeck didn't talk about turf, he was afraid of taking risks, deep down we are terrified. informative and entertaining. He had people "Why is it we're so afraid of change?" Veeck asked. roaring with laughter one minute and reflecting "Because we don't know how to deal with failure." in their thoughts the next. Here's betting that Veeck doesn't hide the fact that he's failed — word gets out about Veeck's talk and he shows he's been fired four times by Major League Base- up more often on the golf turf show circuit. ball teams for trying promotions that went awry. Veeck is the owner of several minor-league For instance, while disco demolition night at baseball teams and the master of many zany Chicago's Comiskey Park in 1979 was a rousing baseball promotions (he holds disco demoli- 'BE OUTRAGEOUS, success in terms of razing disco records, a near tion night to his credit, among others). Unlike riot broke out at the park and the second game some, such as the brash and bratty Randy BE IRREVERENT of the doubleheader had to be canceled. -

Midwest Chapter~S Field Day Better Every Year

MIDWEST CHAPTER~S FIELD DAY BETTER EVERY YEAR BY MIKE SCHILLER, CSFM crisp and clear Friday greeted attendees gathered at Alexian Field, cally placed around the field and covered aspects of baseball field mainte- home of the Schaumburg Flyers of the independent Class A nance, including game day preparations. A Northern League. Eric Fasbender, Director of Field and Stadium Eric covered game day preparations and maintaining the areas around home Operations for the Flyers, hosted this Midwest STMA Chapter event. plate. Connie Rudolph, CSFM, head sports turf manager for the St. Paul First off, the attendees broke into groups, with each assigned a different Saints of the Northern League, covered details of mound building and mainte- starting point of the demonstration/presentation stations, which were strategi- nance. Jeff Eckert, head sports turf manager of the Northern League Joliet Jackhammers, covered maintenance of the skinned infield portion of the field. Jeff Salmond, CSFM, agronomist for Northwestern University, and Dr. Dave Minner, Iowa State University agronomist {see page 54), covered the turf main- tenance segment of field care. Ryan Nieuwsma, head sports turf manager for the Kane County Cougars, Class A affiliate of the Oakland As, covered all aspects of mowing ballfields, including how to make those intriguing patterns that have become a point of aesthetics in many ballparks. During the lunch break, keynote speaker Mike Veeck, promotions and public relations specialist for the Detroit Tigers and joint owner of several minor league baseball clubs, took the floor. Mike, the son of baseball innovator Bill Veeck, is equally innovative if not more so. -

Cover Next Page > Cover Next Page >

cover next page > title : author : publisher : isbn10 | asin : print isbn13 : ebook isbn13 : language : subject publication date : lcc : ddc : subject : cover next page > < previous page page_i next page > Page i < previous page page_i next page > < previous page page_iii next page > Page iii In the Ballpark The Working Lives of Baseball People George Gmelch and J. J. Weiner < previous page page_iii next page > < previous page page_iv next page > Page iv Some images in the original version of this book are not available for inclusion in the netLibrary eBook. © 1998 by the Smithsonian Institution All rights reserved Copy Editor: Jenelle Walthour Production Editors: Jack Kirshbaum and Robert A. Poarch Designer: Kathleen Sims Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gmelch, George. In the ballpark : the working lives of baseball people / George Gmelch and J. J. Weiner. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 1-56098-876-2 (alk. paper) 1. BaseballInterviews 2. Baseball fields. 3. Baseball. I. Weiner, J. J. II. Title. GV863.A1G62 1998 796.356'092'273dc21 97-28388 British Cataloguing-in-Publication Data available A paperback reissue (ISBN 1-56098-446-5) of the original cloth edition Manufactured in the United States of America 05 04 03 02 01 00 99 5 4 3 2 1 The Paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials ANSI Z398.48-1984. For permission to reproduce illustrations appearing in this book, please correspond directly with the owners of the works, as listed in the individual captions. -

Dukakis Taps Sen. Bentsen

MISCELLANEOUS FONSALE DECOR^ivE 30" x M" A U D I SOOOS 1905. 5 speed, plate gloss mirror, loaded. Great shape. dated 1958. Best offer 633-4164.0 S9300 negotiable. Must sell. 643-1454.__________ CADILLAC Fleetwood 1984. Phone, mint con TAB dition. All extras. $9200 SALES or best offer. Coll 643- 4444 o r 244-9501. NOTICE. Connecticut Gen FORD Grand Torino 1975. eral Statute 23-65 prohibits White with blue Inte the postine of advertise rior. Good condition. ments by onv person, firm or corporation on a telegraph, Best offer. 646-4531 telephone, electric light or CHEVY Citation 1980. TOYOTA Pickup 1987. 4 power pole or to a tree, Green with black Inte wheel drive. Excellent shrub, rock, or any other rior. Good condition. condition. Lift kit. Ste natural oblect without o writ Best offer. 646-4531. ten permit for the purpose of reo. $11,000. Call 228- protecting It or the public ond VW Rabbit 1982. Runs 4870. carries o fine of up to S50 for great, 4 new tires, dili G M C 1983 SIS 4x4. Tinted each affense. gently maintained. windows, new short Asking $2500. 646-1375 block, loaded. Asking Coming Soon... leove messoge._______ $5900. 643-8276. 1980 CAMARO Coupe. Beautiful condition. KIM’S Loaded. Best offer. 646- CARS CARS CORNER SHOP 8736 Days and FOR SALE FOR SALE Second hand household weekends._____________ Items, baby clothes and 1980 CAMARO Coupe. baby furniture. Beautiful condition. * CONSMNMENT Loaded. Best otter. 646- CENTER J 8736 Days and AVMUBLE ★ weekends._____________ MOTORS nunuM Ogealag Dale: tagesl Isl MERCURY Monoarch 461 Main St., Manchester I l C P n I ^ A R C 1976. -

Masculinity, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Saturday Night Fever

Networking Knowledge: Journal of the MeCCSA Postgraduate Network, Vol. 4, No. 1 (2011) ARTICLE ‘A straight heterosexual film’: Masculinity, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Saturday Night Fever STELIOS CHRISTODOULOU, University of Kent ABSTRACT Underpinning Saturday Night Fever’s representation of masculinity is a seeming paradox, exemplified in Pauline Kael’s disclaimer that ‘it’s a straight heterosexual film’ despite the obvious similarities to Scorpio Rising’s gay bikers. While Tony Manero is represented as a sexist, homophobic, and racist heterosexual man, he also indulges in the traditionally feminizing activities of disco dancing and self-grooming. This article explores the construction of Tony Manero’s masculinity by taking a closer look at these two activities and situating their cinematic representation in the American cultural context of the late 70s. In the case of disco, a distinction between disco’s gay origins and subsequent entry into mainstream culture explains Fever’s hetero-normative version of disco. The article subsequently turns the attention to the film’s grooming scene, which poses less easily redeemable challenges to Tony’s machismo through intertextual and contextual references to homosexuality. I extrapolate between possible explanations, drawing on Richard Dyer’s work on representation and the discourse on the 70s men’s liberation movement. In the article’s final section, I turn the attention to the connections between masculinity and ethnicity, examining how the 70s revival of ethnicity proposed a historically specific a model of the Italian-American man, unencumbered by the requirements of new masculinities. I argue that Fever replicates this model to infuse into the representation of Tony Manero styles and behaviours that would have otherwise signified homosexuality. -

Disco Demolition Photo Exhibit at Elmhurst Museum

Disco Demolition photo exhibit at Elmhurst museum By George Castle, CBM Historian Posted Friday, July 19, 2013 Disco’s dead. Disco Demolition Night never dies. The most-publicized Bill Veeck promo- tion of all time – and the one that most riotously got away from the Baseball Barnum – is celebrated through Aug. 4 at the Elmhurst Historical Museum, 120 E. Park Ave., Elmhurst. The 1979 event featuring DJ Steve Dahl as ringmaster attracted some 70,000 fans to witness the destruction of thousands of disco records between games of a twinight doubleheader be- tween the White Sox and Detroit Ti- Sox pitcher Ross Baumgarten (left) with Steve Dahl muse Lorelei and another Disco Demolition Night par- gers at old Comiskey Park. Noted rock ticipant. Copyright Paul Natkin - Photo Reserve. photographer Paul Natkin was there as the official shooter of Dahl’s brain- storm party. His work that night, which provokes howls to this day, is part of his overall exhibit, “Shutter to Think: The Rock and Roll Lens of Paul Natkin,” on two floors of the museum, just east of downtown Elmhurst. The Disco Demolition photos, all in black and white, are actually shown in a video re- played continuously on a flat-screen TV on the second floor. The presentation came about, naturally, through a connection with Dahl, who produces his own daily podcast after his decades-long career as a shock jock on Chicago radio ebbed. “The Disco Demolition special exhibit segment to ‘Shutter to Think’ exhibit was put to- gether as an idea when Steve Dahl came through the main exhibit,” said Lance Tawzer, curator of the museum. -

Disco Demolition’ Exhibit Blasts Into Town

CONTACT PERSON: Patrice Roche, Marketing & Communications Specialist Elmhurst History Museum (630) 833-1457 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: May 24, 2017 ‘Disco Demolition’ Exhibit Blasts into Town New exhibit at Elmhurst History Museum chronicles the Night Disco Died ELMHURST, Ill. – The date July 12, 1979 may not immediately ring a bell for every Chicagoan, but for those who spent that summer wearing black band tee shirts, listening to rock music on FM radio, and sporting long, shaggy hairstyles, it stands out as a memorable moment from the scrapbook of their young adult lives—it was the night that disco died. More than a few area residents were at Comiskey Park that night—possibly to see a baseball game—but more than likely to attend Teen Night. The event was envisioned as a hook to fill empty stadium seats in the middle of a dismal White Sox season and promote WLUP’s new deejay, Steve Dahl. Dahl was fostering an anti-disco campaign on Chicago air waves after being fired from a local radio station that switched to a disco format. Fueled by a 98 cent ticket price for fans who brought disco records to blow up between games of the doubleheader, the event quickly careened out of control after 50,000+ attendees packed the park and its environs. In the wake of the explosion, unruly fans took over the field causing baseball fans to shake their heads in dismay and the White Sox to eventually forfeit the second game to the Detroit Tigers. After the smoke cleared, it is said that disco met its demise and Disco Demolition (as it eventually became known) remains one of Chicago’s most infamous baseball history moments. -

House Music: How the Pop Industry Excused Itself from One of the Most Important Musical Movements of the 20Th Century

House Music: How the Pop Industry Excused Itself From One Of The Most Important Musical Movements of The 20th Century By Brian Lindgren MUSC 7662X - The History of Popular Music and Technology Spring 2020 18 May 2020 © Copyright 2020 Brian Lindgren Abstract In the words of house music legend Frankie Knuckles, house music was disco's revenge. What did he mean by that? In many important ways, house music continued where it left off when it was dramatically cast from American society in the now infamous Disco Demolition Night of July 1979. Riding on the wave of many important social upheavals of the 1960s, disco laid a few important foundations for dance music as we know it today. It also challenged the pop industry power-structure by creating new avenues for music to top the Billboard charts. However, in the final analysis the popularity of disco became its undoing. House music continued to ride on a few of the important waves of disco. The longstanding success of house, however, was in a new development: the independent artist/producer. Young people who began to experiment with early consumer electronic instruments were responsible for creating this new genre of music. This new and exciting sound took hold in Chicago, Detroit and the UK before spreading around the world as the sound we know today as house music. 1 Thirty eight years after the term "House Music" was coined in 1982, the genre has incontestably become a global musical and cultural phenomenon. Few genres in music history can claim this kind of influence. -

AUX Cord II Round 4.Pdf

“Yo!, Pass the AUX Cord, You Better Not Read” TRASH set II: The Remix… Questions written by: Dexter Wickham, Zachary Beltz, Caden Stone, Alexandria Hill, Trenton Kiesling, Aleesa Hill, Eliot Chastain, Brendan Morris. Rush Chairman: Joshua Malecki. Questions edited by: Joshua Malecki. The Fort Osage High School. Round 4 1. This man’s ability to wear a suit is referenced in a Gilmore Girls episode, and he was sued by his own record label in 1983 for making albums “unrepresentative” of himself. This man’s 1979 album, Rust Never Sleeps,* features his twin hits, “My My Hey Hey (Out of the Blue)” and “Hey, Hey, My My (Into the Black),” which inspired later grunge music. This man’s 1973 album Harvest features his hits “Old Man,” and a cautionary tale of heroin excess, “The Needle and the Damage Done.” For 10 points, name this Canadian singer, whose hits include “Rockin’ in the Free World,” and “Heart of Gold.” Neil Young 2. The character of Cher Horowitz in Clueless believed that “searching for a boy in high school was as useless as searching for meaning in this actor’s films.” This actor’s career in films was launched from his namesake MTV show which ran from 1990-1995, and his breakthrough film was as Stoney Brown* in 1992’s Encino Man. He followed that with 1993’s Son-in-Law where he plays the college senior Crawl, who meets his girlfriend’s parents for the first time. For 10 points, name this actor, whose “Weasel” persona is known for the catch phrases, like “Hey, BUD-dy” and “grinding.” Pauly Shore (accept either answer) 3.