Cuaderno De Documentacion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethnic Hegemonies in American History

ETHNIC HEGEMONIES IN AMERICAN HISTORY GEORGE HOCKING ______________________ POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY AND HUMAN GENETIC DIVERSITY Western Political philosophy tends toward moral and political uni- versalism: the idea that norms are valid for all human beings. This presupposes either that human beings are biologically pretty much the same, or that human biodiversity is irrelevant to moral and politi- cal issues. Nevertheless, Western political philosophers initially lim- ited their conclusions to ethnically homogeneous regions they knew and understood. Plato’s Republic, for example, portrays an ideal soci- ety for Greeks, not barbarians, and even well past the Enlightenment John Stuart Mill explicitly excluded many non-Europeans from his conclusions in On Liberty.1 Plato and Mill were prescient to do so. Few pre-modern people could travel widely. Consequently most people they knew were much like themselves. But during the Age of Discovery, which started at the end of the fifteenth century, European voyages throughout the world encountered the full richness of Earth’s botanical, zoological, and an- thropological diversity, and efforts to understand it contributed to the seventeenth century’s Scientific Revolution. By 1735, in the Enlightenment’s full flower, Sweden’s Carl Linnaeus developed the system still used to classify Earth’s biodiversity. He ob- served significant morphological differences between the human popu- lations of the different continents, which led him classify these groups as distinct species.2 Such human populations are now called races. The great controversy of our time rages between those who ac- knowledge or deny the existence of distinct races. The race deniers are motivated by the conflict between human biodiversity and philoso- phical or religious forms of universalism. -

THE ASSETS REPORT 2008 a Review, Assessment, and Forecast of Federal Assets Policy

April 2008 THE ASSETS REPORT 2008 A Review, Assessment, and Forecast of Federal Assets Policy Reid Cramer, Rourke O’Brien, and Alejandra Lopez-Fernandini* The purpose of this report is to summarize and take stock of the current state of federal policy through an asset-building lens, especially as it affects the asset base of lower-income families with limited resources, which is the focus of our work. 1 The report is divided into three sections. The first is a review of policy developments in the past year related to asset building, highlighting administration action and significant legislation, including assets-related bills introduced in the first year of the 110th Congress; the second is an examination of the president’s budget proposals for Fiscal Year 2009 from an assets perspective; and the third is a forecast of the assets policy issues that may be considered by Congress during the year or two ahead. A companion report, The 2008 Assets Agenda , to be released in April, will offer a detailed description of a range of policy proposals to broaden savings and asset ownership. The Assets Report 2008—Highlights 2007 Review • The administration responded to the housing crisis by creating the Hope Now Alliance to conduct aggressive outreach to homeowners at risk of delinquency and foreclosure. • FHASecure was launched in response to the housing crisis as a refinancing option for homeowners with non-FHA adjustable rate mortgages. • The IRS began allowing taxpayers to directly deposit their tax refunds in a maximum of three accounts, a change expected to encourage and facilitate saving. -

A Business Lawyer's Bibliography: Books Every Dealmaker Should Read

585 A Business Lawyer’s Bibliography: Books Every Dealmaker Should Read Robert C. Illig Introduction There exists today in America’s libraries and bookstores a superb if underappreciated resource for those interested in teaching or learning about business law. Academic historians and contemporary financial journalists have amassed a huge and varied collection of books that tell the story of how, why and for whom our modern business world operates. For those not currently on the front line of legal practice, these books offer a quick and meaningful way in. They help the reader obtain something not included in the typical three-year tour of the law school classroom—a sense of the context of our practice. Although the typical law school curriculum places an appropriately heavy emphasis on theory and doctrine, the importance of a solid grounding in context should not be underestimated. The best business lawyers provide not only legal analysis and deal execution. We offer wisdom and counsel. When we cast ourselves in the role of technocrats, as Ronald Gilson would have us do, we allow our advice to be defined downward and ultimately commoditized.1 Yet the best of us strive to be much more than legal engineers, and our advice much more than a mere commodity. When we master context, we rise to the level of counselors—purveyors of judgment, caution and insight. The question, then, for young attorneys or those who lack experience in a particular field is how best to attain the prudence and judgment that are the promise of our profession. For some, insight is gained through youthful immersion in a family business or other enterprise or experience. -

The Long New Right and the World It Made Daniel Schlozman Johns

The Long New Right and the World It Made Daniel Schlozman Johns Hopkins University [email protected] Sam Rosenfeld Colgate University [email protected] Version of January 2019. Paper prepared for the American Political Science Association meetings. Boston, Massachusetts, August 31, 2018. We thank Dimitrios Halikias, Katy Li, and Noah Nardone for research assistance. Richard Richards, chairman of the Republican National Committee, sat, alone, at a table near the podium. It was a testy breakfast at the Capitol Hill Club on May 19, 1981. Avoiding Richards were a who’s who from the independent groups of the emergent New Right: Terry Dolan of the National Conservative Political Action Committee, Paul Weyrich of the Committee for the Survival of a Free Congress, the direct-mail impresario Richard Viguerie, Phyllis Schlafly of Eagle Forum and STOP ERA, Reed Larson of the National Right to Work Committee, Ed McAteer of Religious Roundtable, Tom Ellis of Jesse Helms’s Congressional Club, and the billionaire oilman and John Birch Society member Bunker Hunt. Richards, a conservative but tradition-minded political operative from Utah, had complained about the independent groups making mischieF where they were not wanted and usurping the traditional roles of the political party. They were, he told the New Rightists, like “loose cannonballs on the deck of a ship.” Nonsense, responded John Lofton, editor of the Viguerie-owned Conservative Digest. If he attacked those fighting hardest for Ronald Reagan and his tax cuts, it was Richards himself who was the loose cannonball.1 The episode itself soon blew over; no formal party leader would follow in Richards’s footsteps in taking independent groups to task. -

FHFA Foreclosure Prevention Report – 4Q 2008

Federal Housing Finance Agency Foreclosure Prevention Report Disclosure and Analysis of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac Mortgage Loan Data for Fourth Quarter 2008 Federal Housing Finance Agency Foreclosure Prevention Report CONTENTS INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................... 2 OVERALL MORTGAGE PORTFOLIO ............................................................................. 3 DELINQUENT MORTGAGES ........................................................................................ 4 KEY FINDINGS .......................................................................................................... 6 IMPACT OF ENTERPRISE SUSPENSION OF FORECLOSURES...........................................................6 YEAR-OVER-YEAR CHANGES ...........................................................................................7 NEW FORECLOSURES INITIATED .......................................................................................9 FORECLOSURES COMPLETED .......................................................................................... 10 THIRD-PARTY SALES COMPLETED.................................................................................... 10 REAL ESTATE OWNED ACQUISITIONS ............................................................................... 11 REAL ESTATE OWNED INVENTORY ................................................................................... 12 LOSS MITIGATION ACTIONS ......................................................................................... -

Journalists As Investigators and ‘Quality Media’ Reputation

JOURNALISTS AS INVESTIGATORS AND ‘QUALITY MEDIA’ REPUTATION ALEX BURNS (Refereed) Faculty of Business and Law Victoria University [email protected] BARRY SAUNDERS Researcher, Centre for Policy Development [email protected] The current ‘future of journalism’ debates focus on the crossover (or lack thereof) of mainstream journalism practices and citizen journalism, the ‘democratisation’ of journalism, and the ‘crisis in innovation’ around the ‘death of newspapers’. This paper analyses a cohort of 20 investigative journalists to understand their skills sets, training and practices, notably where higher order research skills are adapted from intelligence, forensic accounting, computer programming, and law enforcement. We identify areas where different levels of infrastructure and support are necessary within media institutions, and suggest how investigative journalism enhances the reputation of ‘quality media’ outlets. Keywords investigative methods; journalism, quality media, research skills 1. Research problem, study context and methodology In the land of the blind, the man with a print-out of a Clay Shirky blog is king. (Ben Eltham, Fellow, Centre for Policy Development (Eltham 2009)) 1.1 Study context: The polarised debate on the ‘future of journalism’ It’s currently fashionable in ‘future of journalism’ and similar new media conferences to proclaim the demise of journalists due to social media platforms, and a ‘crisis in innovation’ which may lead to the ‘death of newspapers’. Citizen Journalists who write for local media (Gillmor 2004) and ‘professional amateurs’ or ProAms (Leadbeater and Miller 2004) are portrayed as the preferred future in many university programs on journalism and new media. Some social media proponents even claim, in adversarial language, that journalists co-opt ‘our stories’ from ‘our community’ of bloggers and user-generated content (Papworth 2009). -

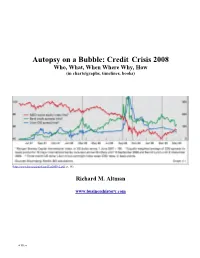

Autopsy on a Bubble: Credit Crisis 2008 Who, What, When Where Why, How (In Charts/Graphs, Timelines, Books)

Autopsy on a Bubble: Credit Crisis 2008 Who, What, When Where Why, How (in charts/graphs, timelines, books) (http://www.bis.org/publ/arpdf/ar2009e2.pdf, p, 16) Richard M. Altman www.businesshistory.com «URLs» Credit Crisis and the Stock Market D I K P P Data - Becomes Information When Interpreted Information - Becomes Knowledge When Understood Knowledge - Becomes Power When Used Power - Becomes Progress When Measured Progress - Becomes Data When Analyzed «URLs» Credit Crisis and Capitalism (http://www.scribd.com/doc/37263162/0061788406, p. 92) «URLs» Credit Crisis and Capitalism (http://www.scribd.com/doc/37263162/0061788406, p. 93) «URLs» Table of Contents 1. Introduction p. 6 a) Cash and Risk p. 6 b) History’s Bubbles p. 7 c) Four Phases of a Bubble p. 8 d) Key Dates p. 12 2. What Happened: Four Stages - Cash, Risk (2) and Rescue p. 13 a) Historical Perspective p. 14 b) Stage 1: 2000-2003 - Cash Grew p. 26 c) Stage 2: 2003-2007 - Credit Risk p. 44 d) Stage 3: 2007-2009 - Market Risk (Event Risk) p. 69 e) Stage 4: 2009-2010 - Rescue: Liquidity and Solvency p. 95 3. People: Who Was Involved p. 115 4. Government/Corporate: When, What, Where (Descriptive) p. 125 a) Government Timeline p. 126 b) Corporate Timeline p. 141 5. Books: Why, How (Interpretive): p. 156 a) Credit Crisis Books (Year, Author) p. 157 b) Credit Crisis: Related Books (Author) p. 180 c) Credit Crisis: Films - (Year, Director) p. 188 d) Wall Street Books (Firm, Year, Author) p. 189 e) Wall Street: Related Books (Author) p. -

Consumer Action

Non-Profit Org. U.S. Postage PAID San Francisco, CA CONSUMER Permit # 10402 ACTION NEWS Change Service Requested 221 Main Street, Suite 480 • San Francisco, California 94105 • www.consumer-action.org • Winter 08-09 About 8,000 homeowners call the HOPE hotline Foreclosure prevention (888-995-HOPE or 4673) About this issue What’s working, what’s not and why everyday. "e Alliance says that it ince mid 2007, the U.S. has been reeling has succeeded in rework- Sfrom an economic crisis that has hit Wall By Ruth Susswein foreclosure crisis through voluntary ing 2.7 million home Street and Main Street with bad news and measures, with little success to date. loans since 2007. But more bad news. couple of hundred people Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson critics charge that more Predatory mortgages and ill-advised lending gathered at a Methodist church and Federal Reserve Chairman Ben than half of these loan have led to a foreclosure crisis, real estate has in Stockton, CA, in December Bernanke handed banks $350 bil- modifications are in fact lost substantial value, lay-offs are crippling Afor a town hall meeting on foreclo- lion in Troubled Asset Relief Program repayment plans that communities, and the stock market, where sure. One homeowner could not hold (TARP) funds with no strings at- simply extend the life of many people invest their retirement savings, back tears as she told of her struggle tached and no commitment for relief the mortgage to 40 years. shed 40% of its value in 2008. to save her home. from the burden of predatory loans According to MSNBC, "is issue focuses on our current state of She is not alone in her emotion. -

Baker Library Core Collection 2/15/07

Baker Library Core Collection 2/15/07 1 Baker Library Core Collection - 2/15/07 TITLE AUTHOR DISPLAY CALL_NO Advanced modelling in finance using Excel and VBA / Mary Jackson and Mike Staunton. Jackson, Mary, 1936- HG173 .J24 2001 "You can't enlarge the pie" : six barriers to effective government / Max H. Bazerman, Jonathan Baron, Katherine Shonk. Bazerman, Max H. JK468.P64 B39 2001 100 billion allowance : accessing the global teen market / Elissa Moses. Moses, Elissa. HF5415.32 .M673 2000 20/20 foresight : crafting strategy in an uncertain world / Hugh Courtney. Courtney, Hugh, 1963- HD30.28 .C6965 2001 21 irrefutable laws of leadership : follow them and people will follow you / John C. Maxwell. Maxwell, John C., 1947- HD57.7 .M3937 1998 22 immutable laws of branding : how to build a product or service into a world-class brand / Al Ries and Laura Ries. Ries, Al. HD69.B7 R537 1998 25 investment classics : insights from the greatest investment books of all time / Leo Gough. Gough, Leo. HG4521 .G663 1998 29 leadership secrets from Jack Welch / by Robert Slater. Slater, Robert, 1943- HD57.7 .S568 2003 3-D negotiation : powerful tools to change the game in your most important deals / David A. Lax and James K. Sebenius. Lax, David A. HD58.6 .L388 2006 360 degree brand in Asia : creating more effective marketing communications / by Mark Blair, Richard Armstrong, Mike Murphy. Blair, Mark. HF5415.123 .B555 2003 45 effective ways for hiring smart! : how to predict winners and losers in the incredibly expensive people-reading game / by Pierre Mornell ; designed by Kit Hinrichs ; illustrations by Regan Dunnick. -

The State of Housing in Black America

The National Association of Real Estate Brokers (NAREB) THE STATE OF HOUSING IN BLACK AMERICA 2013 Commissioned by: Julius Cartwright, NAREB President SHIBA Advisory Board Authored by: James H. Carr, Katrin B. Anacker, and Ines Hernandez NAREB supporting documents compiled by: C. Renée Wilson THE STATE OF HOUSING IN BLACK AMERICA 2013 NAREB 9831 Greenbelt Rd, Lanham, MD 20706 http://www.nareb.com 301-552-9340 Back inner cover graphics examples of work by M2 Magic Media TABLE OF CONTENTS President’s Message ............................................................................................................... iii by Julius Cartwright, President, NAREB Chairman’s Message ...............................................................................................................iv by Lawrence Batiste, Chairman of the Board of Directors, NAREB Foreword .................................................................................................................................v by Dr. Benjamin F. Chavis, Jr, SHIBA Advisor The State of the U.S. Economy and Homeownership for African Americans by James H. Carr, Katrin B. Anacker, and Ines Hernandez Executive Summary Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1 The Current Housing Market and the U.S. Economy .................................................................. 2 The Foreclosure Crisis and Collapse of the U.S. Economy .....................................................................................2 -

The Financial Crisis: a Timeline of Events and Policy Actions February 27, 2007 | Freddie Mac Press Release

The Financial Crisis: A Timeline of Events and Policy Actions February 27, 2007 | Freddie Mac Press Release The Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac) announces that it will no longer buy the most risky subprime mortgages and mortgage-related securities. April 2, 2007 | SEC Filing New Century Financial Corporation, a leading subprime mortgage lender, files for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. June 1, 2007 | Congressional Testimony Standard and Poor’s and Moody’s Investor Services downgrade over 100 bonds backed by second-lien subprime mortgages. June 7, 2007 Bear Stearns informs investors that it is suspending redemptions from its High-Grade Structured Credit Strategies Enhanced Leverage Fund. June 28, 2007 | Federal Reserve Press Release The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) votes to maintain its target for the federal funds rate at 5.25 percent. July 11, 2007 | Standard and Poor’s Ratings Direct Standard and Poor’s places 612 securities backed by subprime residential mortgages on a credit watch. July 24, 2007 | SEC Filing Countrywide Financial Corporation warns of “difficult conditions.” July 31, 2007 | U.S. Bankruptcy Filing Bear Stearns liquidates two hedge funds that invested in various types of mortgage-backed securities. August 6, 2007 | SEC Filing Page 1 of 24 August 6, 2007 | SEC Filing American Home Mortgage Investment Corporation files for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. August 7, 2007 | Federal Reserve Press Release The FOMC votes to maintain its target for the federal funds rate at 5.25 percent. August 9, 2007 | BNP Paribas Press Release BNP Paribas, France’s largest bank, halts redemptions on three investment funds. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 157 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, MARCH 29, 2011 No. 43 House of Representatives The House met at 2 p.m. and was I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the Yvette D. Clarke of New York called to order by the Speaker. United States of America, and to the Repub- Best regards, lic for which it stands, one nation under God, NANCY PELOSI, f indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. Democratic Leader. PRAYER f The Chaplain, the Reverend Daniel P. COMMUNICATION FROM THE f Coughlin, offered the following prayer: CLERK OF THE HOUSE Cherry blossoms draw thousands of ROTARY INTERNATIONAL ASSISTS The SPEAKER pro tempore (Mr. POE visitors to the Capitol city, Lord. Their JAPAN silent beauty causes busy residents to of Texas) laid before the House the fol- stop their frenzied motion and simply lowing communication from the Clerk (Mr. WILSON of South Carolina gaze for a moment. Reflected in pools of the House of Representatives: asked and was given permission to ad- or clustered together on lawns, wrin- HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, dress the House for 1 minute and to re- kled with age, their new life displays a Washington, DC, March 17, 2011. vise and extend his remarks.) unified motion of gentle friendship. Hon. JOHN A. BOEHNER, Mr. WILSON of South Carolina. Mr. Today, in our prayer, Lord, we offer The Speaker, House of Representatives, Speaker, all Americans have provided Washington, DC. voice to their song of spring and praise sympathy for the people of Japan due DEAR MR.