HKFA More Happenings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alternative Digital Movies As Malaysian National Cinema A

Unfolding Time to Configure a Collective Entity: Alternative Digital Movies as Malaysian National Cinema A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Hsin-ning Chang April 2017 © 2017 Hsin-ning Chang. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Unfolding Time to Configure a Collective Entity: Alternative Digital Movies as Malaysian National Cinema by HSIN-NING CHANG has been approved for Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts by Erin Schlumpf Visiting Assistant Professor of Film Studies Elizabeth Sayrs Interim Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT CHANG, HSIN-NING, Ph.D., April 2017, Interdisciplinary Arts Unfolding Time to Configure a Collective Entity: Alternative Digital Movies as Malaysian National Cinema Director of dissertation: Erin Schlumpf This dissertation argues that the alternative digital movies that emerged in the early 21st century Malaysia have become a part of the Malaysian national cinema. This group of movies includes independent feature-length films, documentaries, short and experimental films and videos. They closely engage with the unique conditions of Malaysia’s economic development, ethnic relationships, and cultural practices, which together comprise significant understandings of the nationhood of Malaysia. The analyses and discussions of the content and practices of these films allow us not only to recognize the economic, social, and historical circumstances of Malaysia, but we also find how these movies reread and rework the existed imagination of the nation, and then actively contribute in configuring the collective entity of Malaysia. 4 DEDICATION To parents, family, friends, and cats in my life 5 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor, Prof. -

Hong Kong 20 Ans / 20 Films Rétrospective 20 Septembre - 11 Octobre

HONG KONG 20 ANS / 20 FILMS RÉTROSPECTIVE 20 SEPTEMBRE - 11 OCTOBRE À L’OCCASION DU 20e ANNIVERSAIRE DE LA RÉTROCESSION DE HONG KONG À LA CHINE CO-PRÉSENTÉ AVEC CREATE HONG KONG 36Infernal affairs CREATIVE VISIONS : HONG KONG CINEMA, 1997 – 2017 20 ANS DE CINÉMA À HONG KONG Avec la Cinémathèque, nous avons conçu une programmation destinée à célé- brer deux décennies de cinéma hongkongais. La période a connu un rétablis- sement économique et la consécration de plusieurs cinéastes dont la carrière est née durant les années 1990, sans compter la naissance d’une nouvelle génération d’auteurs. PERSISTANCE DE LA NOUVELLE VAGUE Notre sélection rend hommage à la créativité persistante des cinéastes de Hong Kong et au mariage improbable de deux tendances complémentaires : l’ambitieuse Nouvelle Vague artistique et le film d’action des années 1980. Bien qu’elle soit exclue de notre sélection, il est utile d’insister sur le fait que la production chinoise 20 ANS / FILMS KONG, HONG de cinéastes et de vedettes originaires de Hong Kong, tels que Jackie Chan, Donnie Yen, Stephen Chow et Tsui Hark, continue à caracoler en tête du box-office chinois. Les deux films Journey to the West avec Stephen Chow (le deuxième réalisé par Tsui Hark) et La Sirène (avec Stephen Chow également) ont connu un immense succès en République Populaire. Ils n’auraient pas été possibles sans l’œuvre antérieure de leurs auteurs, sans la souplesse formelle qui caractérise le cinéma de Hong Kong. L’histoire et l’avenir de l’industrie hongkongaise se lit clairement dans la carrière d’un pionnier de la Nouvelle Vague, Tsui Hark, qui a rodé son savoir-faire en matière d’effets spéciaux d’arts martiaux dans ses premières productions télévisuelles et cinématographiques à Hong Kong durant les années 70 et 80. -

Bullet in the Head

JOHN WOO’S Bullet in the Head Tony Williams Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Tony Williams 2009 ISBN 978-962-209-968-5 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Condor Production Ltd., Hong Kong, China Contents Series Preface ix Acknowledgements xiii 1 The Apocalyptic Moment of Bullet in the Head 1 2 Bullet in the Head 23 3 Aftermath 99 Appendix 109 Notes 113 Credits 127 Filmography 129 1 The Apocalyptic Moment of Bullet in the Head Like many Hong Kong films of the 1980s and 90s, John Woo’s Bullet in the Head contains grim forebodings then held by the former colony concerning its return to Mainland China in 1997. Despite the break from Maoism following the fall of the Gang of Four and Deng Xiaoping’s movement towards capitalist modernization, the brutal events of Tiananmen Square caused great concern for a territory facing many changes in the near future. Even before these disturbing events Hong Kong’s imminent return to a motherland with a different dialect and social customs evoked insecurity on the part of a population still remembering the violent events of the Cultural Revolution as well as the Maoist- inspired riots that affected the colony in 1967. -

Download This PDF File

Humanity 2012 Papers. ~~~~~~ “‘We are all the same, we are all unique’: The paradox of using individual celebrity as metaphor for national (transnational) identity.” Joyleen Christensen University of Newcastle Introduction: This paper will examine the apparently contradictory public persona of a major star in the Hong Kong entertainment industry - an individual who essentially redefined the parameters of an industry, which is, itself, a paradox. In the last decades of the 20th Century, the Hong Kong entertainment industry's attempts to translate American popular culture for a local audience led to an exciting fusion of cultures as the system that was once mocked by English- language media commentators for being equally derivative and ‘alien’, through translation and transmutation, acquired a unique and distinctively local flavour. My use of the now somewhat out-dated notion of East versus West sensibilities will be deliberate as it reflects the tone of contemporary academic and popular scholarly analysis, which perfectly seemed to capture the essence of public sentiment about the territory in the pre-Handover period. It was an explicit dichotomy, with commentators frequently exploiting the notion of a culture at war with its own conception of a national identity. However, the dwindling Western interest in Hong Kong’s fate after 1997 and the social, economic and political opportunities afforded by the reunification with Mainland China meant that the new millennia saw Hong Kong's so- called ‘Culture of Disappearance’ suddenly reconnecting with its true, original self. Humanity 2012 11 Alongside this shift I will track the career trajectory of Andy Lau – one of the industry's leading stars1 who successfully mimicked the territory's movement in focus from Western to local and then regional. -

Laurent Courtiaud & Julien Carbon

a film by laurent courtiaud & julien carbon 1 Red_nights_93X66.indd 1 7/05/10 10:36:21 A FILM BY LAURENT COURTIAUD & JULIEN CARBON HonG KonG, CHIna, FranCe, 2009 FrenCH, CantoneSe, MandarIn 98 MInuteS World SaleS 34, rue du Louvre | 75001 PARIS | Tel : +33 1 53 10 33 99 [email protected] | www.filmsdistribution.com InternatIonal PreSS Jessica Edwards Film First Co. | Tel : +1 91 76 20 85 29 | [email protected] SYNOPSIS A CantoneSE OPERA TELLS THE TRAGEDY of THE Jade EXecutioner, WHO HAD created A PoiSon THat KILLED by GIVING THE ultimate PLEASURE. THIS LEGEND HAPPENS AGAIN noWadayS WHEN A FrencH Woman EScaPES to HonG KonG AFTER HAVING KILLED HER loVER to taKE AN ANTIQUE HoldinG, THE infamouS Potion. SHE becomeS THE HAND of fate THat PITS A TAIWANESE GANGSTER AGAINST AN EPicurean Woman murderer WHO SEES HERSELF AS A NEW incarnation of THE Jade EXecutioner. 4 3 DIRECTORS’ NOTE OF INTENT “ Les Nuits Rouges du Bourreau de But one just needs to wander at night along Jade ”. “Red Nights Of The Jade Exe- the mid-levels lanes on Hong Kong island, a cutioner”. The French title reminds maze of stairs and narrow streets connecting of double bills cinemas that scree- ancient theatres, temples and high tech buil- ned Italian “Gialli” and Chinese “Wu dings with silent mansions hidden among the trees up along the peak, to know this is a per- Xia Pian”. The end of the 60s, when fect playground for a maniac killer in trench genre and exploitation cinema gave coat hunting attractive but terrified victims “à us transgressive and deviant pictures, la Mario Bava”. -

Warriors As the Feminised Other

Warriors as the Feminised Other The study of male heroes in Chinese action cinema from 2000 to 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chinese Studies at the University of Canterbury by Yunxiang Chen University of Canterbury 2011 i Abstract ―Flowery boys‖ (花样少年) – when this phrase is applied to attractive young men it is now often considered as a compliment. This research sets out to study the feminisation phenomena in the representation of warriors in Chinese language films from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Mainland China made in the first decade of the new millennium (2000-2009), as these three regions are now often packaged together as a pan-unity of the Chinese cultural realm. The foci of this study are on the investigations of the warriors as the feminised Other from two aspects: their bodies as spectacles and the manifestation of feminine characteristics in the male warriors. This study aims to detect what lies underneath the beautiful masquerade of the warriors as the Other through comprehensive analyses of the representations of feminised warriors and comparison with their female counterparts. It aims to test the hypothesis that gender identities are inventory categories transformed by and with changing historical context. Simultaneously, it is a project to study how Chinese traditional values and postmodern metrosexual culture interacted to formulate Chinese contemporary masculinity. It is also a project to search for a cultural nationalism presented in these films with the examination of gender politics hidden in these feminisation phenomena. With Laura Mulvey‘s theory of the gaze as a starting point, this research reconsiders the power relationship between the viewing subject and the spectacle to study the possibility of multiple gaze as well as the power of spectacle. -

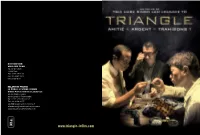

DP TRIANGLE.Indd

DISTRIBUTION WILD SIDE FILMS 42, rue de Clichy 75009 Paris Tél : 01 42 25 82 00 Fax : 01 42 25 82 10 www.wildside.fr RELATIONS PRESSE LE PUBLIC SYSTEME CINEMA Céline Petit & Annelise Landureau 40, rue Anatole France 92594 Levallois-Perret cedex Tel : 01 41 34 23 50 / 22 01 Fax : 01 41 34 20 77 [email protected] [email protected] www.lepublicsystemecinema.com www.triangle-lefi lm.com CADAVRE EXQUIS : Jeu créé par les surréalistes en 1920 qui consiste à faire composer une phrase, ou un dessin, par plusieurs personnes sans qu’aucune d’elles puisse tenir compte de la collaboration ou des collaborations précédentes. En règle générale un cadavre exquis est une histoire commencée par une personne et terminée par plusieurs autres. Quelqu’un écrit plusieurs lignes puis donne le texte à une autre personne qui ajoute quelques lignes et ainsi de suite jusqu’à ce que quelqu’un décide de conclure l’histoire. DISTRIBUTION STOCK Wild Side Films Distribution Service Tél : 01 42 25 82 00 STOCKS COPIES ET PUBLICITÉ Fax : 01 42 25 82 10 Grande Région Ile-de-France www.wildside.fr 24, Route de Groslay 95204 Sarcelles WILD SIDE FILMS DIRECTION DE LA DISTRIBUTION présente Marc-Antoine Pineau COPIES Tél. : 01 34 29 44 21 [email protected] Fax : 01 39 94 11 48 [email protected] Dossier de presse imprimé en papier recyclé PROGRAMMATION Philippe Lux PUBLICITÉ [email protected] Tél. : 01 34 29 44 26 Fax : 01 34 29 44 09 [email protected] MÉDIAS Le premier film réalisé sur le principe du jeu du cadavre exquis Christophe Laduche par les trois maîtres du cinéma de Hong Kong [email protected] LYON 25, avenue Beauregard 69150 Decines DIRECTRICE TECHNIQUE 35MM Brigitte Dutray Tél. -

Written & Directed by and Starring Stephen Chow

CJ7 Written & Directed by and Starring Stephen Chow East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor IHOP Public Relations Block Korenbrot PR Sony Pictures Classics Jeff Hill Melody Korenbrot Carmelo Pirrone Jessica Uzzan Judy Chang Leila Guenancia 853 7th Ave, 3C 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10019 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 212-265-4373 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8833 tel 212-247-2948 fax 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8844 fax 1 Short Synopsis: From Stephen Chow, the director and star of Kung Fu Hustle, comes CJ7, a new comedy featuring Chow’s trademark slapstick antics. Ti (Stephen Chow) is a poor father who works all day, everyday at a construction site to make sure his son Dicky Chow (Xu Jian) can attend an elite private school. Despite his father’s good intentions to give his son the opportunities he never had, Dicky, with his dirty and tattered clothes and none of the “cool” toys stands out from his schoolmates like a sore thumb. Ti can’t afford to buy Dicky any expensive toys and goes to the best place he knows to get new stuff for Dicky – the junk yard! While out “shopping” for a new toy for his son, Ti finds a mysterious orb and brings it home for Dicky to play with. To his surprise and disbelief, the orb reveals itself to Dicky as a bizarre “pet” with extraordinary powers. Armed with his “CJ7” Dicky seizes this chance to overcome his poor background and shabby clothes and impress his fellow schoolmates for the first time in his life. -

Tsui Hark Ringo Lam Johnnie To

TSUI HARK LOUIS KOO A legendary producer and director, Tsui Hark is one of Hong Kong cinema’s most influential figures. A pioneer of the 80’s Hong Kong New — AH FAI Wave film movement, Tsui Hark immediately caught the attention of critics with his innovative style and techniques. “Butterfly Murders” Singer, actor, model – Louis Koo is one of Hong Kong’s most popular Chanteur, acteur, mannequin – Louis Koo est l’une des plus grandes (1979) and “Dangerous Encounters: 1st Kind”(1980) pushed the boundary of Hong Kong genre films as well as the limit of the censors. celebrities. He began his film career in the mid-90’s and has acted in stars de Hong Kong. Il commence sa carrière au milieu des années 90 Following the creation of Film Workshop in 1984, he directed and produced a series of successful commercial films that initiated the so-called over 40 movies such as Wilson Yip’s “Bullet Over Summer”(1999), Tsui et joue dans plus de 40 films, dont « Bullets Over Summer » (1999) de “golden era” of Hong Kong cinema. Films including “A Chinese Ghost Story”(1987), “Swordsman”(1990), and “Once Upon A Time In China” Hark’s “Legend of Zu 2”(2001) and Derek Yee’s “Lost In Time”(2003). Wilson Yip, « La Légende de Zu 2 » (2001) de Tsui Hark et « Lost In (1991) established Tsui Hark's dominance across Asia. After directing two films in Hollywood, he returned to Hong Kong in the mid-90’s Over the past couple of years, he has forged a close working relationship Time » (2003) de Derek Yee. -

Jin Yong's Novels and Hong Kong's Popular Culture Mr Cheng Ching

Jin Yong’s Novels and Hong Kong’s Popular Culture Mr Cheng Ching-hang, Matthew Jin Yong’s martial arts novel, The Book and the Sword, was first serialised in the New Evening Post on 8 February 1955. His novels have been so well received since then that they have become a significant and deeply rooted part of Hong Kong’s popular culture. Jin Yong’s novels are uniquely positioned, somewhere between part literature and part plebeian entertaining read. That is why they have a wide readership following. From serials published in newspapers to films and hit TV drama series, they are at the same time acknowledged by academics as home-grown literature of Hong Kong, and take pride of place in the genre of Chinese novel-writing. The origins of the martial arts novel (also known as the “wuxia novel”) can be traced back to the ancient Shiji (The Records of the Grand Historian), specifically to chapters such as the “Biographies of Knight-errants” and “Men with Swords”. However, the genre draws inspiration from many parts of Chinese history and culture, including the Tang dynasty novels about chivalry, such as Pei Xing’s Nie Yinniang and Du Guangting’s The Man with the Curly Beard; The Water Margin, which was written between the Yuan and Ming dynasties; and the Qing dynasty novels about heroism, such as The Seven Heroes and Five Gallants and Adventures of Emperor Qianlong. In 1915, Lin Shu (Lin Qinnan) wrote a classic Chinese novella, Fumei Records, and its publication in the third issue of the periodical Xiao Shuo Da Guan was accompanied by the earliest use of the term “martial arts novel”. -

The Shifting of Chow Yun-Fat's Star Image Since 1997

7 Translocal Imagination of Hong Kong Connections: The Shifting of Chow Yun-fat’s Star Image Since 1997 Lin Feng Anyone who is interested in Hong Kong cinema must be familiar with one name: Chow Yun-fat (b. 1955). He rose to film stardom in the 1980s when Hong Kong cinema started to attract global attention beyond East Asia. During his early screen career, Chow established a star image as an urban citizen of modern Hong Kong through films such as A Better Tomorrow/Yingxiong bense (John Woo, 1986), City on Fire/Longhu fengyun (Ringo Lam, 1987), All About Ah-Long/A Lang de gushi (Johnnie To, 1989), God of Gamblers/Du shen (Wong Jing, 1989), and Hard Boiled/Lashou shentan (John Woo, 1992). Many Hong Kong film critics claim that Chow’s popularity among local audiences is deeply tied to the rising awareness of Hong Kong’s local identity under the context that the city was undergoing transition from being a British colonial city to becoming the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) in 1997 (Sek Kei et al. 2000). However, after over a decade of prosperity in the 1980s and early 1990s, Hong Kong cinema has been in a long period of recession. Mo Jianwei (2008) notes that the local film industry’s annual production dropped by nearly 40 per cent, from 242 films in 1993 to 150 in 2000. The decline of Hong Kong cinema saw a number of local stars and film-makers migrating overseas. Following his friends and long-time collaborators John Woo, Ringo Lam and Terence Cheung, who moved to America in the early 1990s, Chow also announced his decision to continue his career in Hollywood in 1995. -

INFERNAL AFFAIRS (2002, 101 Min.) Online Versions of the Goldenrod Handouts Have Color Images & Hot Links

November 13 2018 (XXXVII:12) Wai-Keung Lau and Alan Mak: INFERNAL AFFAIRS (2002, 101 min.) Online versions of The Goldenrod Handouts have color images & hot links: http://csac.buffalo.edu/goldenrodhandouts.html DIRECTED BY Wai-Keung Lau (as Andrew Lau) and Alan Mak WRITING Alan Mak and Felix Chong PRODUCED BY Wai-Keung Lau producer (as Andrew Lau), line producers: Ellen Chang and Lorraine Ho, and Elos Gallo (consulting producer) MUSIC Kwong Wing Chan (as Chan Kwong Wing) and Ronald Ng (composer) CINEMATOGRAPHY Yiu-Fai Lai (director of photography, as Lai Yiu Fai), Wai-Keung Lau (director of photography, as Andrew Lau) FILM EDITING Curran Pang (as Pang Ching Hei) and Danny Pang Art Direction Sung Pong Choo and Ching-Ching Wong WAI-KEUNG LAU (b. April 4, 1960 in Hong Kong), in a Costume Design Pik Kwan Lee 2018 interview with The Hollywood Reporter, said “I see every film as a challenge. But the main thing is I don't want CAST to repeat myself. Some people like to make films in the Andy Lau...Inspector Lau Kin Ming same mood. But because Hong Kong filmmakers are so Tony Chiu-Wai Leung...Chen Wing Yan (as Tony Leung) lucky in that we can be quite prolific, we can make a Anthony Chau-Sang Wong...SP Wong Chi Shing (as diverse range of films.” Lau began his career in the 1980s Anthony Wong) and 1990s, serving as a cinematographer to filmmakers Eric Tsang...Hon Sam such as Ringo Lam, Wong Jing and Wong Kar-wai. His Kelly Chen...Dr.