Love Story: an Untelling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Five Kingdoms

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2008 Five Kingdoms Kelle Groom University of Central Florida Part of the Creative Writing Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Groom, Kelle, "Five Kingdoms" (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 3519. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/3519 FIVE KINGDOMS by KELLE GROOM M.A. University of Central Florida, 1995 B.A. University of Central Florida, 1989 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing/Poetry in the Department of English in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2008 Major Professor: Don Stap © 2008 Kelle Groom ii ABSTRACT GROOM, KELLE . Five Kingdoms. (Under the direction of Don Stap.) Five Kingdoms is a collection of 55 poems in three sections. The title refers to the five kingdoms of life, encompassing every living thing. Section I explores political themes and addresses subjects that reach across a broad expanse of time—from the oldest bones of a child and the oldest map of the world to the bombing of Fallujah in the current Iraq war. Connections between physical and metaphysical worlds are examined. -

RCA Victor 12 Inch Popular Series LPM/LSP 4000-4299

RCA Discography Part 13 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA Victor 12 Inch Popular Series LPM/LSP 4000-4299 LSP 4000 – All Time Christmas Hits – Piano Rolls and Voices by Dick Hyman [1968] Winter Wonderland/Silver Bells/It's Beginning To Look Like Christmas/Sleighride/The Christmas Song/I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus/Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow!/The Chipmunk Song/All I Want For Christmas Is My Two Front Teeth/Frosty The Snow Man/White Christmas LSP 4001 – Cool Crazy Christmas – Homer and Jethro [1968] Nuttin' Fer Christmas/Frosty The Snowman/I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus/Santa Claus, The Original Hippie/All I Want For Christmas Is My Upper Plate/Ornaments/The Night Before Christmas/Jingle Bells/Randolph The Flat-Nosed Reindeer/Santa Baby/Santa's Movin' On/The Nite After Christmas LPM/LSP 4002 – I Love Charley Brown – Connie Smith [1968] Run Away Little Tears/The Sunshine Of My World/That's All This Old World Needs/Little Things/If The Whole World Stopped Lovin'/Don't Feel Sorry For Me/I Love Charley Brown/Burning A Hole In My Mind/Baby's Back Again/Let Me Help You Work It Out/Between Each Tear/There Are Some Things LPM/LSP 4003 – The Wild Eye (Soundtrack) – Gianni Marchetti [1968] Two Lovers/The Desert/Meeting With Barbara/The Kiss/Two Lovers/Bali Street/Don't Go Away/The Sultan/All The Little Pictures/The End Of The Orient/Love Comes Back/Nights In Saigon/The Letter/Life Goes On/Useless Words/The Statue/Golden Age/Goodbye/I Love You LSP 4004 – Country Girl – Dottie West [1968] -

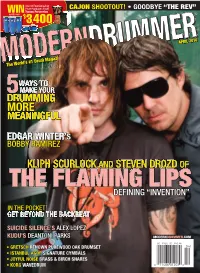

Drumming More Meaningful

One Of Four Amazing Prize Packages From CAJON SHOOTOUT! • GOODBYE “THE REV” WIN Tycoon Percussion worth over $ 3,400 APRIL 2010 The World’s #1 Drum Magazine WAYS TO 5MAKE YOUR DRUMMING MORE MEANINGFUL EDGAR WINTER’S BOBBY RAMIREZ KLIPH SCURLOCK AND STEVEN DROZD OF THE FLAMING LIPS DEFINING “INVENTION” IN THE POCKET GET BEYOND THE BACKBEAT SUICIDE SILENCE’S ALEX LOPEZ KUDU’S DEANTONI PARKS MODERNDRUMMER.COM • GRETSCH RENOWN PUREWOOD OAK DRUMSET • ISTANBUL AGOP SIGNATURE CYMBALS • JOYFUL NOISE BRASS & BIRCH SNARES • KORG WAVEDRUM April2010_Cover.indd 1 1/22/10 10:38:19 AM CONTENTS Volume 34, Number 4 • Cover photo by Timothy Herzog Timothy Herzog Paul La Raia 58 46 42 FEATURES 42 SUICIDE SILENCE’S ALEX LOPEZ 14 UPDATE TESLA’S Over-the-top rock? Minimalist metal? Who cares what bag they put him in— TROY LUCCKETTA Suicide Silence’s drummer has chops, and he knows how to use ’em. ARK’S JOHN MACALUSO 46 THE FLAMING LIPS’ JACKYL’S CHRIS WORLEY 16 GIMME 10! KLIPH SCURLOCK AND STEVEN DROZD BOBBY SANABRIA The unfamiliar beats and tones of the Lips’ trailblazing new studio album, Embryonic, were born from double-drummer experiments conducted in an empty house. How the 36 SLIGHTLY OFFBEAT timekeepers in rock’s most exploratory band define invention. ERIC FISCHER 38 A DIFFERENT VIEW 58 KUDU’S DEANTONI PARKS PETER CASE Once known as a drum ’n’ bass pioneer, the rhythmic phenom is harder than ever to pigeonhole. But for sheer bluster, attitude, and uniqueness on the kit, look no further. 76 PORTRAITS MUTEMATH’S DARREN KING MD DIGITAL SUBSCRIBERS! When you see this icon, click on a shaded box on the MARK SHERMAN QUARTET’S TIM HORNER page to open the audio player. -

2018Verdant.Pdf

Acknowledgements Thanks goes to all of those who helped with Verdant: all contributors of writings; Principal Ginger Gustavson; Assistant Principals Marie Eakin, Maria Edwards, Chenita McDonald and Robert Silvie; Librarians Mrs. Annette Williford and Ms. Pamela Williams; Captain Shreve’s English teachers Mr. Michael Scott and Mrs. Maureen Barclay. Staff Editors: Mary Catherine Douglas Georgia Hilburn Lonniqua James Faculty Advisor: Michael Scott Verdant 18 is a collection of Captain Shreve’s best student writing from the 2017-2018 school year as selected by the Verdant editorial staff. In this collection you will find poetry, prose, and essays that have received recognition from the Scholastic Writing Awards, Seedlings, Artbreak, and the PTSA Reflections Arts Program. Entries are copyright of their respective owners and may be reproduced for personal or educational purposes only. For more information, please contact Michael Scott at [email protected]. 1 Table of Contents Poetry Living With an African Name………………………………………………………………………………………………….10 Naima Bomani Tigerland, My Home Away from Home……………………………………………………………….…………………13 Javin Bowman I am the Warrior……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….………….15 Rachel Clottey The Memories of My Home ………………………………………………………………………………………………………16 Rachel Clottey A Good Man …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..………19 Karissa Cook Beating the Odds ………………..………………………………………………………………………………………………..…….21 Karissa Cook The PC………………………...……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…..22 -

YWP 9.Full .Pdf

Anthology 9 Young Writers Project Dedication to Young Writers Project Founder Geoff Gevalt Young Writers Project owes its vitality to many generous people, but this book is dedicated to the one individual who invented it, persuaded others that it could work, and saw it through at every step of the way for a remarkable 12-year run. Geoff Gevalt is a newspaperman at heart – Young Writers Project actually began as a monthly series in the Burlington Free Press, where he was managing editor – and, like every good journalist, he is energized by the power of words. He understands their ability to inspire and shape lives, and as he built up Young Writers Project, he never lost sight of his belief that young people in their formative years could tap into the magic of writing, and from there, live richer lives, bend the arc of their own life stories and contribute to a better world. Geoff is stepping down this year from full-time duties as executive director, but will continue to contribute in many ways, and his ideals are written into the DNA of our organization. Geoff has touched countless lives. Below is a small sample of his impact on YWPers, past and present: Thank you for teaching this kid from the middle of nowhere that there are people in the world who want to hear the stories floating around in her head. — REBECCA VALLEY, NORTHAMPTON, MASS. Without you, MGMC wouldn’t be a thing. Thank you for the music-filled car rides, the stories you’ve shared and the time you’ve taken to listen. -

The Secret of Father Brown- G.K.Chesterton

The Secret of Father Brown by G. K. Chesterton To father John O’Connor, of St. Cuthbert’s Bradford, whose truth is stranger than fiction, with a gratitude greater than the world THE SECRET OF FATHER BROWN FLAMBEAU, once the most famous criminal in France and later a very private detective in England, had long retired from both professions. Some say a career of crime had left him with too many scruples for a career of detection. Anyhow, after a life of romantic escapes and tricks of evasion, he had ended at what some might consider an appropriate address: in a castle in Spain. The castle, however, was solid though relatively small; and the black vineyard and green stripes of kitchen garden covered a respectable square on the brown hillside. For Flambeau, after all his violent adventures, still possessed what is possessed by so many Latins, what is absent (for instance) in so many Americans, the energy to retire. It can be seen in many a large hotel - proprietor whose one ambition is to be a small peasant. It can be seen in many a French provincial shopkeeper, who pauses at the moment when he might develop into a detestable millionaire and buy a street of shops, to fall back quietly and comfortably on domesticity and dominoes. Flambeau had casually and almost abruptly fallen in love with a Spanish Lady, married and brought up a large family on a Spanish estate, without displaying any apparent desire to stray again beyond its borders. But on one particular morning he was observed by his family to be unusually restless and excited; and he outran the little boys and descended the greater part of the long mountain slope to meet the visitor who was coming across the valley; even when the visitor was still a black dot in the distance. -

Strang • Topal • Gonzalez • Kauffman • Kalamaras Waldrop • Gulin • Beaumont • Argüelles • Lotti • Smith Haupt

STRANG • TOPAL • GONZALEZ • KAUFFMAN • KALAMARAS WALDROP • GULIN • BEAUMONT • ARGÜELLES • LOTTI • SMITH HAUPTMAN • BORDESE • TRETIN • PASSER • HERRICK KOMOR • ZVER • CHIRODEA • LEVINSON • STEWARD ABBOTT • VANDER MOLEN • ANDERSON • LIPSITZ • BEINING BRADLEY • RAPHAEL • CARDINAUX • BENNETT • GRABILL SILVIA CURBELO Ruby Every storm is Jesus chasing spirits, twister blowing through the clothesline of the dead making waves. There’s a sure thing in the high wind, old as some stick in the ground. Time makes an hourglass out of anything. Forget thunder, forget the reckless past. Keep your hymns short and your fuse shorter. Tell your children there’s no free ride to the reckoning, no blaze-of-glory color to paint this wicked world. Blue is some skinny dog lapping brown water on the side of the road. Green is his cup of sorrow. Red is for knowing who’s blind. What Hope Is Think of the weight of tenderness or faith. What is willed, what is opened. The way someone whispers someone’s name into a glass, then empties it, swallowing that small word. Cover: ADAN Y EVA (ADAM AND EVE) by Marcelo Bordese, 2006 acrylic on canvas (47” x 40”) Cover and title page design by Gary R. Smith, 1986 Typeset in Baskerville by Daniel Estrada Del Cid, HS Marketing Solutions, Santa Ana, California Lawrence R. Smith, Editor Deanne C. Smith, Associate Editor Daniel Estrada Del Cid, Production and Design Editor Calibanonline is published quarterly. Viewing online and pdf downloads are free. Unsolicited poetry, fction, art, music, and short art videos welcome. Please direct attached WORD documents to [email protected] Copyright © Calibanonline.com, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS BRIAN STRANG the wasp CARINE TOPAL Sobriquet Passing Smaller Kingdoms St. -

Front Cover.Indd

“Keep the Cat Free” ISSUE 1467 01.10.10 FELIX The student voice of Imperial College London since 1949 INSIDE Your complete guide to Freshers’ Fair The Union President... NAKED!!! FRESHERS’ ISSUE Top 20 Things to do in 1st Year 2 FRIDAY 01 OCTOBER 2010 felix HIGHLIGHTS Your chance to be a student blogger EDITOR’S PICK Union Meetings The Best of Felix This Week At the beginning of the Autumn term, Imperial runs Council a student blogging competition which is open to all students at the College. The winners will have their The first meeting of Union Council is on Monday the own blog on the Imperial website. The blog will be a 11th of October. This will be where the Union’s policy snapshot of your life as a student at Imperial, from on Higher Education will be debated in the coming year, life on campus, to events around London and what amongst other things. All students are welcome so head happened on your summer holidays. along, even if you just want to argue with someone. Ents Committee Sadly not that kind of Ents, this is the place where proposals for club nights are heard. All students can attend but if you want to be a voting member, there will be an election in the first few weeks of term Union Executive Students that are selected to be part of the blog Your guide to gigs in team will receive: The next meeting of the Union Executive is on Thursday • A free digital camera with filming capabilities Freshers’ Week the 7th of October. -

BOOK 1 GRAMMAR (9246 Questions))

INDEXINDEX BOOK 1 GRAMMAR (9246 questions)) PART A: ................................................................................................................................. 2-50 14 Elementary tests, 14 Pre-Intermediate tests, 8 Intermediate tests. Each test is specified on different grammar topics. (1976 questions-) 1-2 PART B:............................................................................................................................. 51-102 14 tests including Elementary, Pre-intermediate, Intermediate and Upper intermediate level grammar tests. Every test is focused on a different grammar topic. (2452 questions) 1-2-3 PART C:........................................................................................................................... 103-150 16 Multi-level grammar tests. Each test is specified on a different grammar topic. (1418 questions) 4 PART D:........................................................................................................................... 151-190 20 perfect multi-level grammar tests for assessment. (2000 questions) 4 PART E: ........................................................................................................................... 191-218 6 Elementary, 5 Intermediate, 3 Advanced grammar tests. The formats of the tests are similar and the level gradually increases. (1400 questions) 1-2-3 BOOK 2 VOCABULARY (5859 questions) PART A: .......................................................................................................................... -

Portraits of Strangers

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2015 Portraits of Strangers Dana Lotito Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Fiction Commons, and the Hawaiian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Lotito, Dana, "Portraits of Strangers" (2015). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 137. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/137 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Portraits of Strangers Dana Lotito 2 Acknowledgements I would first and foremost like to thank the William and Mary English Department for allowing me to pursue an honors thesis in Creative Writing and to my dedicated committee. I also am extremely indebted to the generosity of the John H. Willis Scholarship and the Willis family who granted me the funds to pursue my research to Hawai‘i. Without them, this project would not have been possible. Thank you also to my advisor, Chelsey Johnson, for reading endless drafts and challenging me from every angle to expand my vision for my characters and stories. Thank you to Barbara Rion who helped me brainstorm while we were supposed to be on vacation, to Tim Courtney who listened to me always even when I did not let him read a single word until the very end, to my sister, Lisa, who also read multiple drafts the moment I sent them and gave me invaluable feedback and encouragement, to my other reader Shannon Fineran, and to all my best friends – Sarahbeth, Erin, Sophie, Lauren, Susanne – who listened and supported and encouraged me to keep writing.