The Mask Tradition of Assam with Special Reference to Samaguri Sattra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of External Evaluator, Majuli District

LIST OF EXTERNAL EVALUATOR, MAJULI DISTRICT Designation Contact No of Group Name of External Name of Name of Nodal Contact No of Sl No District PHASE Block Cluster Day Name of School DISE Code Designation Contact No of Liasion Liasion No Evaluator Liasion Officers Teacher Nodal Teacher Officers Officers Assistant MADHYA SRI SRI PITAMBAR DIPAK DAS MINTU KUMAR Teacher 1 MAJULI PHASE - II MAJULI MAJULI 1 DAY - 1 DEV GIRLS HS 18310424105 MADHABI DEVI ASSTT PROFESSOR 7002389721 9435576628 NATH 8638093610 MADHYA SRIMANTA Assistant DIPAK DAS 2 MAJULI PHASE - II MAJULI MAJULI 1 DAY - 2 SANKARDEV LPS 18310424801 MADHABI DEVI ASSTT PROFESSOR 7002389721 Teacher 9435576628 JYOTIKA DAS 9859260258 ROSHMI Assistant MADHYA 2 NO GARAMUR DIPAK DAS RAKHA Teacher 3 MAJULI PHASE - II MAJULI MAJULI 1 DAY - 3 SADAR LP 18310424802 MADHABI DEVI ASSTT PROFESSOR 7002389721 9435576628 BORUAH 8822092142 1.BHUPEN CH DAS, Class VI & VII AEE 9435386980 Assistant DIPAK DAS MADHYA GARMUR SRI SRI 2. PRASANTA Teacher PRANATI 4 MAJULI PHASE - II MAJULI MAJULI 2 DAY - 1 PITAMBAR DEV HS 18310424803 BORTHAKUR, Class SUPERINTENDENT 9954422144 9435576628 HAZARIKA 8723014322 Assistant MADHYA BHUPEN CH DAS DIPAK DAS BIJOY SANKAR Teacher 5 MAJULI PHASE - II MAJULI MAJULI 2 DAY - 2 GOBINPUR LP 18310426701 AEE 9435386980 9435576628 BHARALI 9854215860 Assistant PACHIM ADARSHA BHUPEN CH DAS DIPAK DAS MOHENDRA Teacher 6 MAJULI PHASE - II MAJULI KAMALABARI 2 DAY - 3 BORBARI LP 18310427502 AEE 9435386980 9435576628 REGON 9864584631 MADHYA Assistant DIPAK DAS 7 MAJULI PHASE - II MAJULI MAJULI 3 DAY - 1 MADHUPUR LP 18310424103 HORENDRA NATH CHETIATREASURY OFFICER 9954027839 Teacher 9435576628 KUNTAL BORA 9954151347 GARAMUR Assistant MADHYA MILONPUR DIPAK DAS CHITRALEKHA Teacher 8 MAJULI PHASE - II MAJULI MAJULI 3 DAY - 2 PABONA LP 18310432701 HORENDRA NATH CHETIATREASURY OFFICER 9954027839 9435576628 DUTTA 8011577426 MADHYA 144 NO MORITUNI SUNIL SAIKIA CRCC 9 MAJULI PHASE - II MAJULI MAJULI 4 DAY - 1 SARJAN LP 18310426902 PARUL BORA MILI ASTT PROFESSOR 7086124724 9101049648 MUNIN KAKATI 7896332693 Addl. -

Morphotectonic Evolution of the Majuli Island in the Brahmaputra Valley of Assam, India Inferred from Geomorphic and Geophysical Analysis

Geomorphology 227 (2014) 101–111 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Geomorphology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/geomorph Morphotectonic evolution of the Majuli Island in the Brahmaputra valley of Assam, India inferred from geomorphic and geophysical analysis Siddhartha K. Lahiri a,b,⁎, Rajiv Sinha a a Engineering Geosciences Group, Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur 208016, India b Department of Applied Geology, Dibrugarh University, Dibrugarh 786004, India article info abstract Article history: The Majuli Island, located in the upper reach of the Brahmaputra valley in Assam (India), has reduced in its areal Received 27 April 2013 extent from 787.9 km2 to 508.2 km2 during the period 1915–2005 (35.5% reduction). This amounts to severe Received in revised form 10 March 2014 average erosion of 3.1 km2/yr. All efforts so far to save the island have failed to achieve the desired redress. Accepted 25 April 2014 The engineering approach of ‘Save Majuli’ action plans has focused on quarantining the island from the influence Available online 9 May 2014 of the Brahmaputra River rather than designing long-term process-based solutions anchored on proper under- Keywords: standing of evolution of the relic island. The existing geomorphic model for the evolution of the Majuli Island re- Majuli Island lated its genesis to the great earthquake (M 8.7) in 1750 during which a much smaller palaeo-Brahmaputra thalweg developed an anabranch and captured the Burhi Dihing River. The intermediate land-locked area thereby became basement the Majuli Island that is constituted primarily of the older floodplain deposits. We demonstrate that the evolution structural highs of the Majuli Island has been influenced by fluvial morpho-dynamics, as well as basement configuration and fluvial dynamics tectonic controls. -

Living Intelligently with Floods

BACKGROUND PAPER NO. 5 JUNE 2006 LIVING INTELLIGENTLY WITH FLOODS BY SANJOY HAZARIKA CENTRE OF NORTHEAST STUDIES INDIA This paper was commissioned as an input to the study “Development and Growth in Northeast India: The Natural Resources, Water, and Environment Nexus” Table of contents 1. Background ........................................................................................................................................1 2. Study of flood impacts and control strategies...............................................................................3 2.1 Assam context ...........................................................................................................................3 2.2 Study methodology..................................................................................................................3 3. Study results.......................................................................................................................................4 3.1 Impact of floods on incomes and livelihoods.......................................................................4 3.2 Impact of floods on crops and livestock................................................................................5 3.3 Health problems and health access........................................................................................6 3.4 Government relief measures...................................................................................................6 3.5 Survival strategies ....................................................................................................................8 -

List of Acs Revenue & Election District Wise

List of Assembly Constituencies showing their Revenue & Election District wise break - up Name of the District Name of the Election Assembly Constituency Districts No. Name 1. Karimganj 1-Karimganj 1 Ratabari (SC) 2 Patharkandi 3 Karimganj North 4 Karimganj South 5 Badarpur 2. Hailakandi 2-Hailakandi 6 Hailakandi 7 Katlicherra 8 Algapur 3. Cachar 3-Silchar 9 Silchar 10 Sonai 11 Dholai (SC) 12 Udharbond 13 Lakhipur 14 Barkhola 15 Katigorah 4. Dima Hasao 4-Haflong 16 Halflong (ST) 5. Karbi Anglong 5-Bokajan 17 Bokajan (ST) 6-Diphu 18 Howraghat (ST) 19 Diphu (ST) 6. West Karbi Anglong 7-Hamren 20 Baithalangso (ST) 7. South Salmara 8-South Salmara 21 Mankachar Mankachar 22 Salmara South 8. Dhubri 9-Dhubri 23 Dhubri 24 Gauripur 25 Golakganj 26 Bilasipara West 10-Bilasipara 27 Bilasipara East 9. Kokrajhar 11-Gossaigaon 28 Gossaigaon 29 Kokrajhar West (ST) 12-Kokrajhar 30 Kokrajhar East (ST) 10. Chirang 13-Chirang 31 Sidli (ST) 14-Bijni 33 Bijni 11. Bongaigaon 15-Bogaigaon 32 Bongaigaon 16-North Salmara 34 Abhayapuri North 35 Abhayapuri South (SC) 12. Goalpara 17-Goalpara 36 Dudhnoi (ST) 37 Goalpara East 38 Goalpara West 39 Jaleswar 13. Barpeta 18-Barpeta 40 Sorbhog 43 Barpeta 44 Jania 45 Baghbor 46 Sarukhetri 47 Chenga 19-Bajali 41 Bhabanipur 42 Patacharkuchi Page 1 of 3 Name of the District Name of the Election Assembly Constituency Districts No. Name 14. Kamrup 20-Guwahati 48 Boko (SC) 49 Chaygaon 50 Palasbari 55 Hajo 21-Rangia 56 Kamalpur 57 Rangia 15. Kamrup Metro 22-Guwahati (Sadar) 51 Jalukbari 52 Dispur 53 Gauhati East 54 Gauhati West 16. -

“Majuli Is a Gift to Any Festival” – Tim Cornwell, Scotsman, 14Th August, 2017 Background

“Majuli is a gift to any Festival” – Tim Cornwell, Scotsman, 14th August, 2017 background The Brahmaputra takes birth in China, in western Tibet, and courses through three densely populated, energy-hungry, rapidly modernizing countries — China, India, Bangladesh — before emptying itself into the Bay of Bengal in the massive Ganges-Brahmaputra mangrove delta, the Sundarbans. The Brahmaputra basin is a part of the largest and most populated basin in the world, supporting over 80 million people and rich, rare and endangered biodiversity. What China and India do to this river will directly affect this eco- system. ‘Katha Yatra,’ is our ongoing project, which translates to “a journey of stories”. It explore this river as it enters India until it finds home in the Bay of Bengal, uncovering stories of tradition and change, of wins and losses, of old and new. Through this ‘Yatra,’ we aim to create a research-based body of knowledge of the changing Brahmaputra, encapsulating impressions and understandings of the biodiversity, art, culture, identity, development, the hopes and aspirations of the people inhabiting the banks of the Brahmaputra in the project. The project Katha Yatra is much more than our own artistic ambitions. It aims to bring together the local communities in the region practicing various art forms. Katha Yatra facilitates cultural dialogue with the people from other parts of world. Under this project we also aim to curate workshops, exhibitions, installations and live art that will stimulate people from all over the world. By hosting and curating such artistic activities/events will provide spin-off into other industries that will eventually contribute to the economy of the region. -

Political Science (Diphu)

Data on Mentors-Maintees of the Department of Political Science, Assam University Diphu Campus Name of Mentor: Dr. Niranjan Mohapatra Course No. 405 (Project Work) of the P.G Syllabus, Period: May-2017 SERIAL NAME OF THE STUDENT DISSERTION TOPIC NO 1 Buddhoram Ronghang Karbi Society and Culture : Case Study taralangso 2 Hunmily Kropi Social Status of Karbi: Women: A Case Study of Plimplam Langso Village, Diphu 3 Happy Gogoi Impact of Mid Day Meal on Lower Primary Schools: A Case Study in Selenghat Block Area of Jorhat District 4 Porismita Borah The Functioning of Janani Surakha Yojana 5 Dibyamohan Gogoi Student’s issue: A Case Study of Assam University, Diphu Campus 6 Rishi Kesh Gogoi A Case Study on Lack of Proper Infrastructer in Assam University, Diphu Campus 7 Rustom Rongphar Importance of Bamboo in Karbi Society 8 Mirdan rongchohonpi The Social Status of Women in Karbi Society 9 Birkhang Narzary Domestic Violence Against Women: A Case Study of Rongchingbar Village , Diphu 10 Monjit Timungpi Health Awareness Among the karbi Women: A Case Study of Serlong Village of Karbi Anglong District, Assam 11 Krishna Borah Socio- Economic Condition of Women in Tea Graden: A Case Study of Monabari Tea Estate of Biswanath District of Assam 12 Achyut Chandra Borah Student’s Issue: A Case Study of Assam University, Diphu Campus 13 Jita Engti Katharpi Women Empowerment Through Self Help Group: A Case Study Under Koilamati Karbianglong District , Assam 14 Dipika Das Role of Self Help Group As A Tool For Empowerment of Women: A Case Study of Uttar Barbill -

INDIGENOUS NORTH EAST INDIA.Pdf

INDIA KOLKATA PASIGHAT DAPORIJO MAJULI KOHIMA EAST DIBRUGARH ALONG ZIRO KAZIRANGA KOLKATA Insider Tips: Ÿ In the east and north-eastern part of India, it starts getting dark by 16:30 hours. Day break is at 04:30 hours. Plan the day accordingly. Ÿ Best time for this itinerary: 15 November to 30 April. Ÿ For the past 200 years, Majuli has been celebrating the Along Raas Festival every November, where the life and times of Daporijo Pasighat the Hindu God Krishna are celebrated in all-night live Ziro Dibrugarh performances that last for three days. It is a great time to Majuli Kaziranga be in Majuli. Stay here for two nights. Accommodation Kohima options in Majuli are basic, but neat and clean. Ÿ The Assamese New Year falls during mid-April. Great time to be around to participate in the festivities, music and dance. Kolkata Ÿ Mopin Festival of the Galo Tribe is celebrated at Along during March-April every year when they worship Mopin Ane – the Goddess of Wealth and rub rice flour on their faces as a part of the celebrations. Ÿ Sekrenyi Festival of the Angami Nagas is celebrated over 10-days with its many ceremonies and rituals during the month of February every year near Kohima. It is a purification festival where the ‘body and soul’ of the village are cleansed. It also marks the initiation of young Angami Nagas to adulthood. It harks back to the Angami Nagas' pre-Christian beliefs and traditions in Nagaland which now has the world's largest Baptist Christian population. -

District Disaster Preparedness and Response Plan

District Disaster Preparedness and Response Plan (2019) Name of the District: Majuli (ASSAM) Telephone: +91-03775-274424 Fax: +91-03775-274475, E-Mail: [email protected] Prepared by :- District Administration. 1 Table of Contents Foreword .......................................................................................................... 2 Table of Contents ............................................................................................. 3 1 Introduction .............................................................................................. 5 1.1 Background………………………………………………………………….. 5 1.2 Importance of multi hazard management plan…………………… 7 1.3 The main features of multi hazard plan……………………………….. 7 1.4 Disaster Management Cycle………………………………………. 7 1.5 Pre Disaster or Risk Management Phase……………………….. 8 1.6 Post- Disaster or Crisis Management Phase………………………… 8 1.7 Objective of the plan………………………………………….. 8 2.1 Majuli- Administrative Profile .................................................................... 8 2.2 Disasters.................................................................................................... 9 2.3 Flood ................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Erosion ................................................................................................ 11 2.5 Earth-Quake ...................................................................................... 14 2.6 Cyclone ............................................................................................ -

Reimagining a Violent Landscape: Disaster

REIMAGINING A VIOLENT LANDSCAPE: DISASTER, DEVELOPMENT, AND CARTOGRAPHIC IMAGINATION IN THE BRAHMAPUTRA RIVER VALLEY by Kevin Inks A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science (Geography) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON 2019 i ABSTRACT The physical geography of India's Brahmaputra River, one of the world's largest braided rivers, is characterized by constant shift. Communities along the river experience frequent and intense flooding, and displacement due erosion and flood damage is common. Majuli, the world’s largest river island, is experiencing both erosion and creation of ‘new’ lands along its borders due to high sediment deposition. Having not been surveyed in nearly fifty years, 'new' lands formed from sediment deposition in Majuli are untitled and government-owned, and communities settled on these lands are not entitled to resettlement assistance. The adaptation and migration strategies adopted by residents of these informal settlements are poorly understood. Semi-structured interviews and comprehensive surveys focused on perceptions of risk, efficacy of disaster relief, and migration strategies were conducted with households identified as being at-risk of catastrophic flooding and erosion in Majuli District, Assam. Interviews with policymakers, government workers, and religious leaders were conducted to assess disaster relief efforts in informal settlements. The results suggest that policymakers’ static understanding of land shapes flooding patterns and migration regimes. Members of informal settlements at high risk of displacement adapt to the lack of government assistance by altering adaptation and migration strategies, but are largely constrained to repeated informal resettlement on un-surveyed land. More effective and flexible surveying practices, in combination with expanded disaster relief, are essential to minimize displacement and work towards a new understanding of geomorphology, land tenure, and disaster management as dynamic, intertwined processes. -

List of Acs Revenue & Election District Wise

List of Assembly Constituencies showing their Revenue & Election District wise break - up Name of the District Name of the Election Assembly Constituency Districts No. Name 1. Karimganj 1-Karimganj 1 Ratabari (SC) 2 Patharkandi 3 Karimganj North 4 Karimganj South 5 Badarpur 2. Hailakandi 2-Hailakandi 6 Hailakandi 7 Katlicherra 8 Algapur 3. Cachar 3-Silchar 9 Silchar 10 Sonai 11 Dholai (SC) 12 Udharbond 13 Lakhipur 14 Barkhola 15 Katigorah 4. Dima Hasao 4-Haflong 16 Halflong (ST) 5. Karbi Anglong 5-Bokajan 17 Bokajan (ST) 6-Diphu 18 Howraghat (ST) 19 Diphu (ST) 6. West Karbi Anglong 7-Hamren 20 Baithalangso (ST) 7. South Salmara 8-South Salmara 21 Mankachar Mankachar 22 Salmara South 8. Dhubri 9-Dhubri 23 Dhubri 24 Gauripur 25 Golakganj 26 Bilasipara West 10-Bilasipara 27 Bilasipara East 9. Kokrajhar 11-Gossaigaon 28 Gossaigaon 29 Kokrajhar West (ST) 12-Kokrajhar 30 Kokrajhar East (ST) 10. Chirang 13-Chirang 31 Sidli (ST) 14-Bijni 33 Bijni 11. Bongaigaon 15-Bogaigaon 32 Bongaigaon 16-North Salmara 34 Abhayapuri North 35 Abhayapuri South (SC) 12. Goalpara 17-Goalpara 36 Dudhnoi (ST) 37 Goalpara East 38 Goalpara West 39 Jaleswar 13. Barpeta 18-Barpeta 40 Sorbhog 43 Barpeta 44 Jania 45 Baghbor 46 Sarukhetri 47 Chenga 19-Bajali 41 Bhabanipur 42 Patacharkuchi Page 1 of 3 Name of the District Name of the Election Assembly Constituency Districts No. Name 14. Kamrup 20-Guwahati 48 Boko (SC) 49 Chaygaon 50 Palasbari 55 Hajo 21-Rangia 56 Kamalpur 57 Rangia 15. Kamrup Metro 22-Guwahati (Sadar) 51 Jalukbari 52 Dispur 53 Gauhati East 54 Gauhati West 16. -

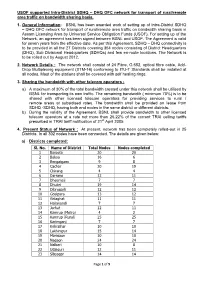

USOF Supported Intra-District SDHQ – DHQ OFC Network for Transport of Rural/Remote Area Traffic on Bandwidth Sharing Basis

USOF supported Intra-District SDHQ – DHQ OFC network for transport of rural/remote area traffic on bandwidth sharing basis. 1. General Information: BSNL has been awarded work of setting up of Intra-District SDHQ – DHQ OFC network for transport of rural/remote area traffic on bandwidth sharing basis in Assam Licensing Area by Universal Service Obligation Funds (USOF). For setting up of the Network, an agreement has been signed between BSNL and USOF. The Agreement is valid for seven years from the effective date. As per this Agreement, SDHQ – DHQ connectivity is to be provided in all the 27 Districts covering 354 nodes consisting of District Headquarters (DHQ), Sub Divisional Headquarters (SDHQs) and few en-route locations. The Network is to be rolled out by August 2012. 2. Network Details : The network shall consist of 24 Fibre, G.652, optical fibre cable, Add- Drop Multiplexing equipment (STM-16) conforming to ITU-T Standards shall be installed at all nodes. Most of the stations shall be covered with self healing rings. 3. Sharing the bandwidth with other telecom operators : a) A maximum of 30% of the total bandwidth created under this network shall be utilised by BSNL for transporting its own traffic. The remaining bandwidth ( minimum 70%) is to be shared with other licensed telecom operators for providing services to rural / remote areas at subsidised rates. The bandwidth shall be provided on lease from SDHQ -SDHQ, having both end nodes in the same district or different districts. b) During the validity of the Agreement, BSNL shall provide bandwidth to other licensed telecom operators at a rate not more than 26.22% of the current TRAI ceiling tariffs prescribed in TRAI tariff notification of 21st April 2005. -

ASSAM STATE DISASTER MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY Maaistrats Wi Eh Case O Rural Areas in the Last One Week, District

GOVERNMENT OF ASSAM ASSAM STATE DISASTER MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY Ancilary Block, Janata Bhawan, Dispur, Guwahati-781006 Phone: 0361-2237221 (O): E-mail: [email protected] ORDER No. ASDMA.28/2021/92 Dated 15 June, 2021 Whereas, the Assam State Disaster Management Authority (ASDMA) has oorders of May 4, 2021, May 12. 2021, May 15, 2021 and May 17, 2021 have Se certan directives related to Containment Zones. gatherings, work places. educational insttutions, publIC transport, restnction on movement of individuals ncuding night curfew, restricbion on inter-district transport senvices and penal provsions or both rura and urban areas across the State of Assam for containment of COviD-19 pandemic in Assam. Whereas, the Assam State Disaster Management Authority (ASDMA) has vide order of May 25, 2021 issued directives on restrictive measures for containment of CoviD-19 in both rural and urban areas across the State upto June 5, 2021. Whereas, the Assam State Disaster Management Authority (ASDMA) has vide order of 2021 June 4, issued directives on curfew hours. gathenings, work places and inter-doveen to De uniromy applicable in both rural and urban areas across the State upto 5 AM of June 16, 202. Whereas, the Ministry of Home Alfairs (MHA) vide order dated 27" May. 2021 has urged the States/ UTs to continue compliance to the containment measures as enviseged in MHA order dated 29th April,2021 till 30 June, 2021. Whereas, the situation of CoviD-19 in the State observed that, the number of has been reviewed and though COvib-19 patients and positivity rate is declining in some districts, the overall Is containment measures for bothsituation urban andstill rural precarious, areas are for stll whichadequate necessary tor containment of CoviD-19 across the State.