US Corn Sweeteners and Mexican Sugar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reliability and Condition Monitoring Solutions for the Sugar Production Industry Why Partner with Bently Nevada? We Have Earned Your Trust

Reliability and condition monitoring solutions for the sugar production industry Why partner with Bently Nevada? We have earned your trust. For six • Increased availability and production • Over 85,000 3500 Series monitoring decades the Bently Nevada product line systems installed globally • Lowered maintenance costs has supported the most demanding • Over 4 million sensor applications in multiple industries. And • Reduced risk in terms of safety, monitoring points even as we protect and monitor your environmental, and asset upsets • Services support globally machinery, we constantly strive to refine Quantifiable, proven results: and improve our offerings—and help • Over 1,600 System 1 software • Over 60 years of innovation in asset enable your success. users worldwide protection and condition monitoring We design and deliver solutions for all • More than 240 international patents of your monitoring needs—including issued, including over 150 in the U.S. sensors, distributed and rack-based monitors, software, and supporting • More than 360 international patents services—with the following goals: pending, including over 95 in the U.S. Industry challenges Sugar is virtually in everything we consume, including alternative fuels in many parts of the world. Table sugar is extracted from the roots of sugar beets and the stalks of sugarcane. It’s a big business: The world produces more than 78 million tons (71 metric tons) of sugarcane annually [source: The Sugar Bureau]. It can take up to 18 months for new cane stalks to be ready for harvest, and harvesting is often done now by machines on large plantations. Processing and packaging often occurs very close to the harvest location to prevent the harvested cane or beets from rotting. -

MINIMIZATION of SUCROSE LOSSES in SUGAR INDUSTRY by Ph and TEMPERATURE OPTIMIZATION

The Malaysian Journal of Analytical Sciences, Vol 12, No 3 (2008): 513 - 519 MINIMIZATION OF SUCROSE LOSSES IN SUGAR INDUSTRY BY pH AND TEMPERATURE OPTIMIZATION Kornvalai Panpae 1*, Wasna Jaturonrusmee 1, Withawat Mingvanish 1 , Chantana Nuntiwattanawong 2, Surapon Chunwiset 2 , Kittisak Santudrob 1 and Siriphan Triphanpitak 1 1Department of Chemistry , Faculty of Science , King’s Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi, Bangkok 10140, Thailand 2Chaimongkol Refined Sugar Company, Limited.( U-Thong Factory ), Supanburi Province 72160, Thailand * Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Invert sugar has several disadvantage properties that play an important role in many food applications. It has a high affinity for water and is the cause of making products retain moisture.Invert sugar also affects the caramelization process , producing a browning effect. In this study, the possibility of minimization of sucrose inversion during the industrial production of sugar cane was investigated by the variation of the important parameters, i.e. temperature and pH of sugar cane juice for each of samples. The amounts of sucrose and reducing sugar alerting during the sucrose inversion process were determined by the values of % Pol and % reducing sugar (% RS), respectively. Starting with the study of temperature and pH effects of the sucrose solution with the concentration of 16 Brix, used as a sample model, it was found that no change in amounts of reducing sugar and sucrose was observed at room temperature (34 oC) in the pH range of 5-11. At pH 3, the amounts of reducing sugar increased and the amount of sucrose decreased as the time increased. -

Submission for Sugar Price Review in the Domestic Market

Submission for Sugar Price Review in the Domestic Market 12 JUNE 2021 “Ensuring a Financially Viable FSC for Future” Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 2 2 Overview ........................................................................................................................................ 4 3 Fiji Sugar Corporation – Backbone of Fiji .................................................................................. 4 3.1 History ......................................................................................................................................... 4 3.1.1 Pre-Colonial Era .................................................................................................................. 4 3.1.2 Independence and Post-Colonial Era ............................................................................... 4 3.2 Alignment of FSC’s Strategic Objectives towards National Development Plan ............... 5 3.3 Challenges ................................................................................................................................... 5 3.4 FSC Now ...................................................................................................................................... 6 3.4.1 Changes Required to Rectify the Ailing Situation .......................................................... 7 4 Importance of FSC to Fiji’s Economy ........................................................................................ -

THE SUGAR BEE'l' INDUSTRY of the ARKANSAS VALLEY of COLQUDO

THE SUGAR BEE'l' INDUSTRY OF THE ARKANSAS VALLEY OF COLQUDO By THOMAS PATRICK DEAN I• Bachelor ot Arts Oklahana Agricultural and Mechanical College Stillvater, Oklahcaa 19Sl Suhm1tted to the Faculty of the Graduate Sohool of the Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechard.cel College in Partial. Fulf1llment of tba Requirements tar tba Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE 1954 ii OKLA ffui!f l AIIICULTURAL & M£CIWUCAL ~UEGt LIBRARY JUN 181954 THE SUGAR BEET INDtS'l'RY OF Tl£ .ARKANSAS VALIEI OF COLCRADO Thesis Adviser .. Dean of the Graduate Sohool 321653 THESIS TITIE: THE SUGAR BEET INDtBTRY OF THE ARKANSAS VALLEY OF COLOR.ADO AUTHCR: ffl<JWS PATRICK DEAtf THESIS ADVISER: DR. EDWARD E. KESO The conteut and form have been checked and approved by the author and thesis adviser. The Graduate School Office assumes no responsibility for errars either in form or content. The copies ere sent to the bindery just as they e:re api:roved by the author and fe.culty adviser. ffPIST: GOB.DON F • CULVER iii PREFACE The -writer first became a.cqu.ainted with the sugar beet while pr:te paring a research paper on sources of foods. He was amazed at the wide distribution of the industry in the United States and the percentage of sugar the industry supplies to this country's market. A more detailed study revealed that, in certain areas in the United States, sugar beet production has been on the decline for a number of years. This study of a specific area was therefore undertaken in an effort to discover the cause or ca.uses for this decrease. -

Studies in Cane Sugar Refining

Scholars' Mine Professional Degree Theses Student Theses and Dissertations 1927 Studies in cane sugar refining Marion Smith Badollet Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/professional_theses Part of the Chemical Engineering Commons Department: Recommended Citation Badollet, Marion Smith, "Studies in cane sugar refining" (1927). Professional Degree Theses. 64. https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/professional_theses/64 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars' Mine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Professional Degree Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholars' Mine. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDIES III CANE 3UG.AR 11E}?I1:IIUG ;.. ";(... ~~~, ~3 BY MARION SMITH BADOLL£T A THESIS Submitted to the faculty of the SCHOOL OF UIJJ.ES AND METALLUHGY OF ~1iE UUDTERSllY OF ~ISSOURI in partial fLl.lfillment of the work required -:for the Degree of CHE1tICAL ]NGIlr.EER Rolla, Mo. 1927. Atproved Application of the Dye Test to Sugar-House Products and Relations Between Certain Measurements and the Refining Quality of Raw Cane Sugar'~ J1, S. Badol/ot awl H. S. Paine (C'arlwhydrafc Laboratory, Bllrca'l~ Of Chemistry, lJ. S, Deparllllent of .1yri('lllturc) Investigation of the effect of colloids upon of a motor-operated stirrer, to keep the filter the refining qualityl of raw cane sugars is one medium (infusorial eal,tTi) in uniform suspen of the important subjects in the refining indus- sion during the filtration period, The l1ressure try today. -

From the Field to the Table

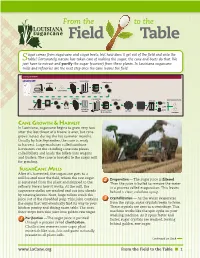

From the to the Field Table A Comparison of Beet Sugar Processing and Cane Sugar Refining SUGAR BEET PROCESSING FACTORY ugar comes from sugarcaneFILTRA andTION sugarFIL beets,TRATION but how does it get out of the field and onto the SUGAR BEET CENTRIFUGALS FOOD MANUFACTURER SLICING STORAGE Stable? Fortunately, nature has taken care of making the sugar; the cane and beets doBULK that. We LIQUID just have to extract andCARBONA purifyTION the sugar (sucrose) from these plants. In Louisiana sugarcane WASHING DIFFUSION CRYSTALLIZATION BAGS DRYERS SCREENS mills and refineries are the next stepEVAPORA onceTORS the cane IN VACCUM leaves PANS the field. CONSUMER CANE SUGAR REFINERY SUGARCANE EVAPORATORS FILTRATION CENTRIFUGALS CRUSHING CLARIFICATION RAW SUGAR MILL VACCUM PANS CENTRIFUGALS FILTRATION EVAPORATORS CENTRIFUGALS FOOD MANUFACTURER STORAGE BULK MINGLER LIQUID MELTER CHARCOAL RAW SUGAR WAREHOUSE FILTRATION CRYSTALLIZATION BAGS COLUMNS DRYERS SCREENS IN VACCUM PANS CONSUMER CANE GROWTH & HARVEST In Louisiana, sugarcane begins to grow very fast after the last threat of a freeze is over, but cane grows fastest during the hot summer months. Usually by late September, the cane is ready to harvest. Large machines called combine harvesters cut the standing cane into pieces called billets and loads the billets into wagons and trailers. The cane is brought to the sugar mill for grinding. SUGARCANE MILLS After it’s harvested, the sugarcane goes to a mill located near the field, where the raw sugar 2 Evaporation — The sugar juice is filtered. is separated from the plant and shipped to the Then the juice is boiled to remove the water refinery. Here’s how it works: At the mill, the in a process called evaporation. -

Sugar Beets Cultivation of Sugar Cane

NATURAL Sweet by Nature From the Field to the Table has been an important food ingredient for thousands of years. But, there is more to sugar’s story than you may think, including Math, Science, History and Geography. TABLE OF CONTENTS n One Sweet History n Where Does Sugar Come From? Map it Out n Sugar - Captured Sunshine n A Closer Look At Sugar n From the Field to the Table n It’s Sweet To The Environment n Sugar - More Than Just Sweet Taste! n A Sweet Part Of A Healthy Diet! www.sugar.org ONE Sweet HISTORY… n Spanish they call it “azucar.” “Sucre” is Sugar is one of the world’s the French word for it, while Germans say oldest documented I“zucker.” It’s called many things in many commodities, and at one places, but as long as it’s been around, and it’s time it was so valuable that been a while, Americans have always called it people locked it up in what “sugar.” was called a sugar safe. SUGAR’S OLD AND ILLUSTRIOUS TIMELINE: In the beginning, sugar Christopher Columbus 8000 B.C. cane was valued for 1493 is credited with the sweet syrup it produced. As people introducing sugar cane to migrated to different parts of the world, the New World, but that the good news spread, and eventually, was old news in places sugar cane plants were found in like Southeast Asia where Southeast Asia, India, and Polynesia. sugar had already been making life sweeter for A new form of sugar over 8,000 years. -

SUMMING-UP of the CONFERENCE Mr J.N

1 SUMMING-UP OF THE CONFERENCE Mr J.N. Greenfield, Director, Commodities and Trade Division, FAO. For most of the developing countries in the region, the link of sugar to food security was an issue. While sugar is a good source It is my task to draw a few conclusions from two days of intensive of food in its own right, it was often grown in competition for discussions on sugar in the world and of course with particular reference food grain (rice and maize). However sugar earnings wee to the Asia/Pacific region. usually vital for the food security of the farmers, particularly the small farmers. I would like to divide this summary into three parts - first our discussions on overall sugar market developments, secondly the There was a lot of interest in the use of bagasse as a source of country studies and thirdly something on the global policy energy as well as other uses. More or less all countries reported environment. on developments in this area. The third part of our proceedings concerned developments in First on the world sugar market, it was agreed that the industry has the overall world trading system and its implications for world been undergoing a period of considerable change, a lot of deregulation sugar policy. I refer to such developments as the Uruguay has been going on, partly linked to development in global policy Round, discussions on the Lomé Convention and discussions on changes as reflected in the Uruguay Round. An important change that the continuation of the reform process scheduled to begin in we discussed is the improved world market stability. -

Alternative and Supplementary Health Model On

tion utri & W N e f i o g l h t a L n r o u s s o J Journal of Nutrition & Weight Loss Review Article Alternative and Supplementary Health Model on Traditional Sugars Karthikeyan Nagarajan*, Acharya Balkrishna , Paran Gowda University of Patanjali, Patanjali Yogpeeth, Haridwar, India ABSTRACT This article reviews nutraceutical properties of traditionally processed sugar products in view of food policy implications in India. This review gains importance in the light of overconsumption of foods rich in sugar, salt and fat, in the recent decades, and the associated epidemic of non-communicable diseases in India and rest of the world. Food policy in India does not signify the traditional sugars. We have presented an alternative health model to analyse nutraceutical properties of traditional sugars and distinguish them from refined sugars. We have evolved this model using ancient health wisdom of India. Traditional sugars are distinct from refined sugars by composition, nutritional benefits, rate of energy release and medicinal values. The traditional sugars are rich in nutraceuticals properties while the refined sugars are of empty calories. Research proofs show that the traditional sugars possess immunological properties, cyto-protective features, anti-toxicity effects and anti-cariogenic characteristics. The traditional products have also been proved to have positive health effects on diabetes and hypertension. Yet, the refined sugar products do not possess such properties. We recommend the policy makers to take action to list the nutraceutical properties of the traditional sugars in international scientific databases. We also suggest the policy makers of India that traditional sugars need to be distinguished from refined sugars in food labeling standards. -

White and Refined Sugar Production from Cane Sugar Factory

First Biennial World Conference On Recent Development in Sugar Technologies Marriott Hotel, Delray Beach, Florida, USA, May 16-17, 2002 White and Refined Sugar Production from Cane Sugar Factories Dr. Chung Chi Chou, Principal Scientist, Dr. Chou Technologies, Inc. USA E-Mail: [email protected] Website: esugartech.com Drs. Khalid Iqbal, Y. G. Min, D. W. Gao and Emmanuel Duffaut, formerly Research scientists/ Engineers, Sugar Processing Research Institute, USA Introduction Sugar from sugar cane is extracted today much the same as it was 40 years ago. Sugar extracted from sugar cane is processed to become raw sugar at sugar mills and then further purified to refined white sugar in a sugar refinery, using energy intensive processes. However, sugar from beet is processed to refined white sugar directly in a beet factory. Volumes of research have been conducted on nature of colorants, polysaccharide and inorganic profile of sugar process streams over the past thirty (30) years. However very few research priority have been directed to develop a sugar process that will produce the same quality sugar at cane sugar factories that is currently provided at sugar refineries at a significant reduction in energy consumption. Dr. Chung Chi Chou, while he was the managing director of Sugar Processing Research Institute (SPRI) during 1999 / 2000, organized and directed a team to conduct a research project with the objective specifically to produce white/refined sugar directly in sugar factories. The team succeeded in their effort and developed the “SAT” process to produce white sugar using clarified juices from Sterling sugar factory in Louisiana. Both the bench scale boiling pan at SPRI and pilot scale boiling pan at Audubon Sugar Institute of Louisiana State University were used for this study. -

Mclean Museum and Art Gallery, Greenock the Sugar Industry

McLean Museum and Art Gallery, Greenock The Sugar Industry The refining of 1st large refinery built in 1765 by Mark Kuhll at the bottom of Sugarhouse Lane sugar came to be associated with Greenock for over two hundred years. Colonial connections, initially with the slave colonies in the West Indies, ensured a supply of the raw material for processing and later imperial expansion led to the Greenock sugar trade pursuing business in almost all parts of the world. The refining trade made several dynastic business fortunes and these families came to have an important role in the business and politics of nineteenth century Greenock. Greenock's first refinery was erected about 1765 by Mark Kuhll at the bottom of Sugarhouse Lane. Thereafter the trade expanded rapidly and by 1881 eleven refineries were in operation including John Walker & Co. and Neill, Dempster & Neill, Westburn Refineries Ltd. With economic power cam political influence and Abraham Lyle, whose firm later amalgamated with that of Joseph Tate, became a Provost of Greenock. In the 19th century Greenock was second only to London as producer of sugar. There were still three refineries present in the 1950s. Now, however, there are none; the Westburn Refinery, owned by Tate & Lyle Ltd., being the last refinery to close on 29th August 1997. McLean Museum and Art Gallery – Greenock Sugar Industry – Web Leaflet 1 Portrait of Abram Lyle (1820-1891) as Provost of Greenock. 'The produce of the Clyde refineries, and of Greenock in particular, equals, if it does not excel that of any sugar refining port in Europe, as the prizes awarded at the Great Exhibitions of 1851 and 1862 doubtless testify. -

Imperial Sugar Company Port Wentworth, Georgia February 7, 2008 Key Issues

U.S. CHEMICAL SAFETY AND HAZARD INVESTIGATION BOARD INVESTIGATION REPORT SUGAR DUST EXPLOSION AND FIRE (14 Killed, 36 Injured) IMPERIAL SUGAR COMPANY PORT WENTWORTH, GEORGIA FEBRUARY 7, 2008 KEY ISSUES: • COMBUSTIBLE DUST HAZARD RECOGNITION • MINIMIZING COMBUSTIBLE DUST ACCUMULATION IN THE WORKPLACE • EQUIPMENT DESIGN AND MAINTENANCE Report No. 2008-05-I-GA September 2009 Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..........................................................................................................................1 1.0 INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................3 1.1 Background.........................................................................................................................3 1.2 Investigative Process...........................................................................................................5 1.3 Imperial Sugar Company ....................................................................................................6 1.3.1 Corporate Governance............................................................................................6 1.3.2 Corporate and Facility Management ......................................................................7 1.4 Facility Description.............................................................................................................8 1.4.1 Granulated Sugar Storage Silos............................................................................10 1.4.2 Silos