Interview with the Right Rev. Rodney R. Michel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dean and the Deanery

7 DIOCESE OF EAST ANGLIA Diocesan policy on THE DEANERY AND THE ROLE OF THE DEAN THE DEANERY How is the universal Catholic Church structured? The whole people of God is a communion of dioceses, each entrusted to the pastoral leadership and care of a bishop. The diocese is then ‘divided into distinct parts or parishes’ (Code of Canon Law, 374.1). Each parish is by nature an integral part of the diocese. What then is a deanery? ‘To foster pastoral care by means of common action, several neighbouring parishes can be joined together in special groupings, such as deaneries’ (Code of Canon Law, 374.2). Each deanery is led by a Dean appointed by the bishop to act in his name. In a scattered diocese such as ours, with many small parishes, working together in deaneries can be very fruitful, not only for the mutual support and care of the clergy, but also for pastoral and spiritual collaboration at local level. In each deanery, there are to be regular meetings of the clergy, priests and deacons, diocesan and religious, of that grouping of parishes. All are expected to attend such meetings and participate as fully as possible in deanery life and work. In each deanery, there are to be regular meetings of lay representatives of each parish with all the clergy of the deanery, so as to facilitate active participation by lay people in local pastoral action and decision-making. The following norms for the role of the Dean came into effect from 21 November 2003. THE ROLE OF THE DEAN 1. -

Archdiocese of Indianapolis Deanery and Parish Maps Deaneries 1

Archdiocese of Indianapolis The Church in Central and Southern Indiana Archdiocese of Indianapolis Deanery and Parish Maps Deaneries 1. Indianapolis North Deanery Dean: Very Rev. Guy Roberts, VF 4217 Central Ave., Indianapolis, IN 46205........................................ 317-283-5508 009 Immaculate Heart of Mary, 030 St. Luke the Evangelist, Indianapolis Indianapolis 012 Christ the King, Indianapolis 033 St. Matthew the Apostle, 014 St. Andrew the Apostle, Indianapolis Indianapolis 038 St. Pius X, Indianapolis 025 St. Joan of Arc, Indianapolis 041 St. Simon the Apostle, Indianapolis 029 St. Lawrence, Indianapolis 043 St. Thomas Aquinas, Indianapolis 2. Indianapolis East Deanery Dean: Rev. Msgr. Paul D. Koetter, VF 7243 E. 10th St., Indianapolis, IN 46219 ..........................................317-353-9404 001 SS. Peter and Paul Cathedral, 032 St. Mary, Indianapolis Indianapolis 037 St. Philip Neri, Indianapolis 004 Holy Cross, Church of the, 039 St. Rita, Indianapolis Indianapolis 042 St. Therese of the Infant Jesus 007 Holy Spirit, Indianapolis (Little Flower), Indianapolis 011 Our Lady of Lourdes, 072 St. Thomas the Apostle, Indianapolis Fortville 018 St. Bernadette, Indianapolis 079 St. Michael, Greenfield 3. Indianapolis South Deanery Dean: Very Rev. James R. Wilmoth, VF 3600 S. Pennsylvania St., Indianapolis, IN 46227 ............................ 317-784-1763 005 Holy Name of Jesus, Church 022 SS. Francis and Clare of Assisi, of the Most, Beech Grove Greenwood 006 Holy Rosary, Our Lady of the 026 St. John the Evangelist, Most, Indianapolis Indianapolis 010 Nativity of Our Lord Jesus 028 St. Jude, Indianapolis Christ, Indianapolis 031 St. Mark the Evangelist, 013 Sacred Heart of Jesus, Indianapolis Indianapolis 036 St. Patrick, Indianapolis 015 St. Ann, Indianapolis 040 St. -

Great Cloud of Witnesses.Indd

A Great Cloud of Witnesses i ii A Great Cloud of Witnesses A Calendar of Commemorations iii Copyright © 2016 by The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America Portions of this book may be reproduced by a congregation for its own use. Commercial or large-scale reproduction for sale of any portion of this book or of the book as a whole, without the written permission of Church Publishing Incorporated, is prohibited. Cover design and typesetting by Linda Brooks ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-962-3 (binder) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-966-1 (pbk.) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-963-0 (ebook) Church Publishing, Incorporated. 19 East 34th Street New York, New York 10016 www.churchpublishing.org iv Contents Introduction vii On Commemorations and the Book of Common Prayer viii On the Making of Saints x How to Use These Materials xiii Commemorations Calendar of Commemorations Commemorations Appendix a1 Commons of Saints and Propers for Various Occasions a5 Commons of Saints a7 Various Occasions from the Book of Common Prayer a37 New Propers for Various Occasions a63 Guidelines for Continuing Alteration of the Calendar a71 Criteria for Additions to A Great Cloud of Witnesses a73 Procedures for Local Calendars and Memorials a75 Procedures for Churchwide Recognition a76 Procedures to Remove Commemorations a77 v vi Introduction This volume, A Great Cloud of Witnesses, is a further step in the development of liturgical commemorations within the life of The Episcopal Church. These developments fall under three categories. First, this volume presents a wide array of possible commemorations for individuals and congregations to observe. -

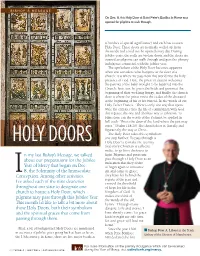

HOLY DOORS Holy Door Is to Make the Journey Istock That Every Christian Is Called to Make, to Go from Darkness to N My Last Bishop’S Message, We Talked Light

BISHOP’S MESSAGE On Dec. 8, this Holy Door at Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome was opened for pilgrims to walk through. (churches of special significance) and each has its own Holy Door. These doors are normally walled up from the inside and could not be opened every day. During jubilee years, the walls are broken down and the doors are opened so pilgrims can walk through and gain the plenary indulgence connected with the jubilee year. The symbolism of the Holy Door becomes apparent when one considers what happens at the door of a church: it is where we pass from this world into the holy presence of God. Here, the priest or deacon welcomes the parents of the baby brought to be baptized into the Church; here, too, he greets the bride and groom at the beginning of their wedding liturgy; and finally, the church door is where the priest meets the casket of the deceased at the beginning of his or her funeral. In the words of our Holy Father Francis, “There is only one way that opens wide the entrance into the life of communion with God: this is Jesus, the one and absolute way to salvation. To Him alone can the words of the Psalmist be applied in full truth: ‘This is the door of the Lord where the just may enter.’” (Psalm 118:20) The church door is, literally and figuratively, the way to Christ. The Holy Door takes this symbolism one step further. To pass through a HOLY DOORS Holy Door is to make the journey iStock that every Christian is called to make, to go from darkness to n my last Bishop’s Message, we talked light. -

Lighting of the Advent Candles

Our Lady of Lourdes, Mineral Wells, TX Thirty-third Sunday in Ordinary Time MASS SCHEDULE & MASS INTENTIONS FROM THE PASTOR’S DESK Nov. 12 - Nov. 18 Jesus foretold many signs that would shake peoples and nations. The signs which God uses are Saturday - Nov. 12 meant to point us to a higher spiritual truth and reality of his kingdom which does not perish or fade 4:30 P.M. - St. Francis, Graford Joan Kohlhass † away, but endures for all eternity. God works through many events and signs to purify and renew us 6:30 P.M. - Chapel ............................... Mark Renner † in hope and to help us set our hearts more firmly on him and him alone. How would you respond if Sunday - Nov. 13 someone prophesied that your home, land, or place of worship would be destroyed? 9:00 A.M. - English .......................... Kevin Rasberry † 11:30 A.M. - Spanish ........................ Mary Sanchez † Wednesday Nov. 16 LIGHTING OF THE JUBILEE YEAR OF MERCY: 7:00 A.M. - Chapel ...................... Juana S. Villarreal † South West Deanery will conclude the Jubilee Year Thursday - Nov. 17 ADVENT CANDLES: of Mercy celebrations on Thursday November 17. 6:30 P.M. - Deanery Jubilee Year of Mercy Chapel We will have confessions from 5:00 p.m. to 6:00 (Mass by the Most Rev. Bishop Michael Olson First Sunday ...................................... Youth p.m. Holy Eucharist will be celebrated by Most Rev. for SW Deanery) Second Sunday ........... PreK-6th Grade CCD Bishop Michael Olson at 6:30 p.m. We will have Friday - Nov. 18 Third Sunday ................... Jr.& Sr. High CCD people come from other parishes that belong to our 7:00 A.M. -

Organizational Structures of the Catholic Church GOVERNING LAWS

Organizational Structures of the Catholic Church GOVERNING LAWS . Canon Law . Episcopal Directives . Diocesan Statutes and Norms •Diocesan statutes actually carry more legal weight than policy directives from . the Episcopal Conference . Parochial Norms and Rules CANON LAW . Applies to the worldwide Catholic church . Promulgated by the Holy See . Most recent major revision: 1983 . Large body of supporting information EPISCOPAL CONFERENCE NORMS . Norms are promulgated by Episcopal Conference and apply only in the Episcopal Conference area (the U.S.) . The Holy See reviews the norms to assure that they are not in conflict with Catholic doctrine and universal legislation . These norms may be a clarification or refinement of Canon law, but may not supercede Canon law . Diocesan Bishops have to follow norms only if they are considered “binding decrees” • Norms become binding when two-thirds of the Episcopal Conference vote for them and the norms are reviewed positively by the Holy See . Each Diocesan Bishop implements the norms in his own diocese; however, there is DIOCESAN STATUTES AND NORMS . Apply within the Diocese only . Promulgated and modified by the Bishop . Typically a further specification of Canon Law . May be different from one diocese to another PAROCHIAL NORMS AND RULES . Apply in the Parish . Issued by the Pastor . Pastoral Parish Council may be consulted, but approval is not required Note: On the parish level there is no ecclesiastical legislative authority (a Pastor cannot make church law) EXAMPLE: CANON LAW 522 . Canon Law 522 states that to promote stability, Pastors are to be appointed for an indefinite period of time unless the Episcopal Council decrees that the Bishop may appoint a pastor for a specified time . -

Diocesan DEANERY

Catholic Diocese of Richmond Parishes by Deanery Diocese of Arlington 33 Blessed Sacrament Holy Infant DEANERY 11 Elkton Fredericksburg 250 Shepherd of the Hills Saint Francis of Assisi 220 340 Quinque Saint John the Evangelist Incarnation Charlottesville Catholic School Saint Mary of the Immaculate Conception Annunciation Saint Andrew Crozet Catholic Saint Thomas Aquinas Holy Comforter the Apostle Community Mission Hot Springs Saint Jude Shrine of the Sacred Heart Ladysmith DEANERY 7 Buckner Saint Timothy Chincoteague Is. Saints Peter and Paul Palmyra 301 13 Saint George Shalom House DEANERY 6 Saint Joseph Retreat Center Sacred Heart Saint Joseph’s Shrine of St. Katharine Drexel Saint Patrick Saint Mary Clifton Montpelier Forge Scottsville 360 Saint Ann Ashland DEANERY 10 Our Lady Saint Peter Columbia of Lourdes the Apostle Saint Michael Church & School Onley All Saints 29 Church of School Vietnamese Church of the DEANERY 12 Martyrs Redeemer DEANERY 5 60 Saint 220 15 Paul Benedictine Our Lady of the Blessed Sacrament College Prep Saint Mary Saint Saint Saint Church of Church & Bridget Benedict Peter Saint Saint the Visitation School School Church & Church & Elizabeth John 81 Blessed Sacrament/ School School Huguenot School Saint Edward the Confessor Saint Saint Elizabeth Gertrude Cathedral Holy Quinton Topping (Middlesex Co.) Saint John Saint Francis of Assisi School of the Rosary Ann Seton West Point the Evangelist Sacred Heart Saint Edward- Sacred Saint Epiphany School Heart Saint John Neumann Saint Patrick Buckingham 60 Joseph Church -

The Diocesan Synod

The Diocesan Synod A Brief Summary of the Institution of the Diocesan Synod and A Preview of our Second Diocesan Synod Definition of a Synod An assembly or “coming together” of the local Church. Code of Canon Law c. 460 A diocesan synod is a group of selected priests and other members of the Christian faithful of a particular church who offer assistance to the diocesan bishop for the good of the whole diocesan community... Purpose of a Synod What’s the purpose of a Diocesan Synod? 1. Unity – brings the Diocese together 2. Reform and Renewal o Teaching o Spirituality 3. Assess/Implement Best Practices o Pastoral o Financial 4. Communicate Info – from Rome/USCCB 5. Legislate practical Norms o To aid: Pastors, Vicars, Business Managers, Parish Secretaries, Diocesan Officials, Lay faithful, etc… Purpose of a Synod What a Synod is not… A Diocesan Synod is not a ‘be all to end all’ pastoral plan Rather, a Diocesan Synod is intended to meet the current practical needs of the Church and is to be renewed when those needs change (~ 8-10 years) A Synod provides (when needed) pastoral and administrative ‘housecleaning’. First Diocesan Synods Rooted in 2 ancient practices The presbyterate meeting to share in the governance of the local church Bishops of an area/province gathering to address issues of common concern Why were they needed? Heresies threatened Church Teaching Schisms threatened Church Unity Lax Behavior (clergy:) threatened Evangelization First Diocesan Synods Historically, Dioceses were more so municipal, city- centered entities with the Bishop and his clergy being located very closely geographically. -

Fund-Raising for a Medieval Monastery: Indulgences and Great Bricett

FUND-RAISING FOR A MEDIEVAL MONASTERY: INDULGENCES AND GREAT BRICETT PRIORY' by R.N. SWANSON ALTHOUGH THEY TEND to evokederision and dismissalbecauseof their associationwith Chaucer's Pardoner and Luther's onslaught on catholicism,indulgences were, arguably, one of the fundamental and most ubiquitouselements of pre-Reformationreligion.They were certainlymuch utilised as a means of fund-raising,and that very exploitation attests their popularity. Yetthe mechanismsfor such fund-raising are often obscure, dependent on scattered evidenceand chancesurvivals.One cacheof materialwhichthrowssomelight on the collectingprocess now survivesamong the archivesof King'sCollege,Cambridge, concerning the priory of Great Bricett in Suffolk. The priory wasfounded in the seconddecade ofthe 12thcentury by Ralph son of Brien. Its early historyis ambiguous:although linked to the French monasteryof St Léonard-de- Noblat (now in Haute Vienne), it was only at the end of the 13th century that it was recognised as fully dependent on that house, thereby definitively entering the ranks of that fairly large group of small monasterieswhich, because of those foreign connections,are collectivelyknown as the alien priories.2The eventual fate of mostof those houses,during the course of the Anglo-Frenchwarsof the 14thand 15thcenturies, wasto be confiscation by the Crown, with their properties —and their records —in many casespassing to other bodies. Great Bricett, like several other such establishments,was used by Henry VI to provide some of the endowment for his collegiatefoundation -

Introduction to Catholicism 6.30 Pm Program of Catholic Studies (M) [email protected]

St Mary’s Catholic Church @ @ @ @ @ Greenville, South Carolina 8 September 2019 Dear Friends in Christ, In my preaching and teaching, I urge all Catholics to read and study the Bible regularly, and from those who accept that invitation, I often get this question: Which Bible should I use? Today I write to suggest three different books, each containing the same translation of Holy Scripture. The Bible has been translated into English many times in the past five centuries, and each translation has its own advantages and disadvantages. The translation that I use for my own prayer and study is called the Revised Standard Version - Second Catholic Edition, and this is the text I recommend to others. Inside our eBulletin this week you’ll find ordering information on three different Bibles which contain this same translation, and if you are looking for a new Bible for your prayer and study, any of these would be a good choice. The first book is published by Ignatius Press, and it is called simply The Holy Bible (Revised Standard Version - Second Catholic Edition). This Bible contains a few notes on most pages to connect verses in one book to those of another, but it is not a study Bible. This text is primarily for personal reading and prayer, particularly lectio divina. Of special interest locally, the cover of this Bible is the art work of Christopher Pelicano, a parishioner of St Mary’s. The second book is published by the Midwest Theological Forum in concert with Ignatius Press, and it is called The Didache Bible (Revised Standard Version - Second Catholic Edition). -

Greek Catholic Metropolitan Church Sui Iuris in Slovakia and Greek Catholic Church in the Czech Republic Within the Current Catholic Canon Law

E-Theologos, Vol. 2, No. 1 DOI 10.2478/v10154-011-0005-2 Greek Catholic Metropolitan Church sui iuris in Slovakia and Greek Catholic Church in the Czech Republic within the Current Catholic Canon Law František Čitbaj University of Prešov, Faculty of Greek-Catholic Theology Introduction The aim of this contribution is to inform lawyers, above all canon lawyers, of the current legal situation of the Greek Catholic Church in Slo- vakia, as well as in Czech Republic, and about changes which these com- munities underwent in the previous years, and what these changes meant for them. Basic characteristics: The Greek Catholic Church in Slovakia („řécko- katolícka církev“in Czech) is one of the twenty-two Catholic Churches of the Eastern rite. Originating in the Constantinopolitan traditions it uses Byzantine-Slavic rite in the liturgy. Canonically, it is part of the Catholic Church, respecting the authority of the successor to St. Peter the Apostle, the high priest of Rome. One of its other specifics in comparison to the Latin Church lies in granting the sacrament of priesthood to married men. The liturgical life in the Greek Catholic Church is diverse and plentiful. Liturgy is the most important means of not only prayer, but also theologi- cal cognition and spiritual life. Its disciplinary order is present in the Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches which together with the Code of Can- non Law from 1983 and apostolic constitution Pastor bonus from 1988 create the current legal order of Catholic Churches. It was promulgated in 1990 by Pope John Paul II. -

Delegate Handbook Volume 2 Deanery and Parish Reports

Delegate Handbook Volume 2 Ver September 21st, 2012 Deanery and Parish Reports Diocese of the West Orthodox Church in America 2012 Diocesan Assembly October 2-4, 2012 Meeting at Holy Transfiguration of Christ Cathedral 349 East 47th Avenue Denver, CO 80216 2012 DOW Assembly 1 Delegate Book 2 Version September 21st, 2012 2012 DOW Assembly 2 Delegate Book 2 Table of Contents Volume 2 Desert Deanery.....................................................................................................................5 St. Paul the Apostle Church (1988) – Las Vegas, NV ...................................................6 Saints Peter and Paul Orthodox Church (1951) – Phoenix, AZ ....................................8 St. John of Damascus Orthodox Church (1976) – Poway, CA ....................................11 St. Nicholas Orthodox Church (1940) – San Diego, CA .............................................14 Missionary District Deanery ............................................................................................ 16 Archangel Gabriel Orthodox Mission (1997) – Ashland, OR .....................................18 St Jacob of Alaska Mission (2003) – Bend, OR ..........................................................20 St Nicholas of South Canaan Orthodox Church (1988) – Billings, MT ......................22 St. Anthony the Great Orthodox Mission (1999) – Bozeman, MT .............................24 SS Cyril and Methodius Orthodox Mission (1999) - Chico, CA .................................26 Joy of All Who Sorrow Mission (2000) – Culver