Frontier Nursing Service, 1925-1940

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birthin'babies: the History of Midwifery in Appalachia

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 464 795 RC 023 530 AUTHOR Buchanan, Patricia; Parker, Vicky K.; Zajdel, Ruth Hopkins TITLE Birthin' Babies: The History of Midwifery in Appalachia. PUB DATE 2000-10-00 NOTE 10p.; Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Women of Appalachia: Their Heritage and Accomplishments (2nd, Zanesville, OH, October 26-28, 2000). PUB TYPE Historical Materials (060) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Birth; *Certification; Folk Culture; *Nonformal Education; *Nursing Education; Rural Education; *Rural Women; Social History; Training IDENTIFIERS *Appalachia; Appalachian Culture; Frontier Nursing Service; Kentucky; Midwives; Nurse Midwives ABSTRACT This paper examines the history of midwifery in Appalachia. Throughout history, women in labor have been supported by other women. Midwives learned as apprentices, gaining skills and knowledge from older women. Eventually, formalized training for midwives was developed in Europe, but no professional training existed in the United States until 1939. In 1923 Mary Breckinridge organized the Frontier Nursing Service in Wendover, Kentucky, to meet the health needs of rural women and children. Breckinridge had become acquainted with nurse-midwives in France and Great Britain during World War I and later attended classes in London. She brought trained midwives from England, who made prenatal home visits on foot or horse. In 1939 the Frontier Nursing Service started the Frontier School of Midwifery and Family Nursing, which still exists today. It is estimated that a quarter of all certified American nurse-midwives graduated from the Frontier School. In 1989 the school began offering a national distance-learning program to make it easier for nurses in small towns and rural areas to become nurse-midwives. -

Federal University Hospitals and Stochastic Frontier Model

Texto para Discussão 022 | 2017 Discussion Paper 022 | 2017 Federal University Hospitals and Stochastic Frontier Model Romero C. B. Rocha Instituto de Economia, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro André Médici Banco Mundial This paper can be downloaded without charge from http://www.ie.ufrj.br/index.php/index-publicacoes/textos-para-discussao Federal University Hospitals and Stochastic Frontier Model July, 2017 Romero C. B. Rocha Instituto de Economia, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro André Médici Banco Mundial Resumo O objetivo deste trabalho é caracterizar os Hospitais Universitários Federais (HUFs) brasileiros em termos de sua importância, suas fraquezas, suas fortalezas e suas necessidades. Além disso, o trabalho vai analisar a relação entre os HUFs e o sistema hospitalar SUS, tentando explicar como eles podem melhorar a qualidade do atendimento e racionalizar esta relação. Revisitamos alguns estudos para entender a melhor maneira dos hospitais organizarem sua governança. Finalmente, rodamos um modelo de fronteira estocástica no intuito de construir rankings de eficiência para os hospitais e analisar o quanto eles poderiam aumentar sua produção com os insumos que possuem. Os resultados encontrados nos estudos revisitados mostram que a melhor maneira de organizar a governança é através do modelo de Organizações Sociais (OS), na qual o governo contrata um operador privado sem fins lucrativos para administrar as unidades. No entanto, as unidades continuam sendo propriedade do governo e 100% financiada pelo governo sob um contrato de desempenho baseado em resultado com riscos financeiros. Os resultados encontrados no modelo de fronteira mostram que os hospitais estão mais perto da eficiência na produção ambulatorial que na produção hospitalar. -

Finding Aid to the Breckinridge Family Photograph Collection, 1865-1915 Collection Number: 012PC25

Finding Aid to the Breckinridge Family Photograph Collection, 1865-1915 Collection number: 012PC25 The Filson Historical Society Special Collections Department 1310 S. Third Street Louisville, KY 40208 [email protected] (502) 635-5083 Finding Aid written by: Heather Stone Date Completed: April 2013 © 2013 The Filson Historical Society. All rights reserved. Breckinridge Family Photograph Collection Page 1 of 17 COLLECTION SUMMARY Collection Title Breckinridge Family Photograph Collection Collection Number 012PC25 Creator Attributed to various photographic studios Dates 1865-1915 Bulk Dates 1865-1893 Physical Description 138 photographic items, varying in formats: Tintypes, Cabinet Cards, Carte de Visite (CDV), Real Photograph Post Cards, Mounted Photographs, Silver Gelatins, and Albumen Silver Prints. Repository Special Collection Department, The Filson Historical Society, Louisville, KY Abstract The photograph collection is predominately of the Breckinridge family of Cabell’s Dale, Kentucky (outside of Lexington), their relatives, and some friends. The collection features portraits, Grove Hill the Virginia Breckinridge’s family home, interior shots of General Joseph Cabell, Sr. and Louise Dudley’s family home and images from abroad. The collection documents the family from 1865-1915. The majority of the photographs are of Joseph Cabell Breckinridge, Sr. and his family; others include Robert Jefferson Breckinridge, Sr. and Charles Henry Breckinridge. Breckinridge Family Photograph Collection Page 2 of 17 Language The collection materials are in English. Note(s) INFORMATION FOR RESEARCHERS Access and use restrictions Collection is available for use. Full credit must be given to The Filson Historical Society. Conditions governing the use of photographic/videographic images do apply. Contact the Photograph Curator for more details on use. -

Breckenridge, Clarence Edward, Papers, 1897-1960, (C1037)

C Breckenridge, Clarence Edward, Papers, 1897-1960 1037 .2 linear feet This collection is available at The State Historical Society of Missouri. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. INTRODUCTION Family correspondence, newspaper clippings, miscellaneous typed notes on Breckenridge genealogy and the Breckenridges’ historic role in early American and southeast Missouri history. Many families included who were distantly related to the Breckenridges. Presbyterian Church history. Majority of correspondence with Adella Breckenridge Moore, Herman F. Harris, and James M. Beckenridge. DONOR INFORMATION The papers were donated to the State Historical Society of Missouri by Clarence Edward Breckenridge on 12 December, 1962 BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Clarence Edward Breckenridge (1877-1963) of Greensboro, North Carolina was the brother of William Clark Breckenridge, St. Louis businessman, writer and historian, and James Malcolm Breckenridge, former St. Louis lawyer. They were descendents of Alexander Breckenridge, who came to Virginia from North Ireland in 1780. The Breckenridge family had an important role in the early history of Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, Illinois and Missouri. Clarence was with the real estate division of American Express Company. Upon his retirement in 1950, he continued the genealogical work begun by his brother James. Clarence Edward Breckenridge died in 1963. FOLDER LIST f. 1 Correspondence, 1900-1939. Letters on Breckenridge genealogy from James M. Breckenridge, St. Louis businessman, historian and collector of Missouri and western history, to Adella Breckenridge Moore, Caledonia, Missouri. One letter to Judge George Breckenridge, Caledonia. Description of San Francisco earthquake, St. Louis streetcar strike. f. 2-5 Correspondence, 1950-1957. Correspondence of Clarence E. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

i 1. I NFS Form 10-900 OM8 Mo. 1024-0018 (R«V. 846) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places NATIONAL Registration Form REGISTER This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property historic name Frontier Nursing Service other names/site number Frontier Nursing Service Complex_______________________ 2. Location street & number Hospital Hill |_| not for publication N/A city, town Hyden I I vicinity N/A state Kentucky code KY county Leslie code 131 zipcode41749 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property UTI private I I building(s) Contributing Noncontributing PI public-local fx~| district 1 buildings I I public-State [~lsite 1 sites I I public-Federal I I structure 1 structures EH object ____ objects 3 Total Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources previously N/A_____________ listed in the National Register ___"Q" 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this (XJ nomination I I request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Health Professions Act: List of Approved Facilities for Purposes Of

114 No. 36936 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 16 OCTOBER 2013 No. 797 16 October 2017 HEALTH PROFESSIONS ACT, 1974 (ACT NO. 56 OF 1974) LIST OF APPROVED FACILITIES FOR THE PURPOSES OF PERFORMING COMMUNITY SERVICE BY SPEECH LANGUAGE AND HEARING THERAPISTS IN THE YEAR 2014 The Minister of Health has, in terms of regulation 5.1 of the Regulations relating to Performance of Community Service by Persons Registering in terms of the Health Professions Act, 1974 (Act No. 56 of 1974), listed the following approved facilities for purposes of the profession of speech and hearing therapy. PROVINCE REGION/DISTRICT FACILITY EASTERN CAPE AMATOLE (Allocated professionals to rotate within the cluster) Buffalo City/Amahlathi Cluster Bhisho Hospital Cathcart Hospital Grey Hospital* Nompumelelo Hospital * S.S GidaHospital* East London Complex Cecilia Makiwane Hospital Empilweni Gompo Hospital Frere Hospital Bedfort Hospital Nkonkobe Cluster Fort Beaufort Hospital Victoria Hospital Tower Hospital(Psychiatry Hospital) Mbashe Cluster Madwaleni Hospital Butterworth Hospital Mnquma Cluster Ngqamakhwe CHC Tafalofefe Hospital ALFRED NZO (Allocated professionals to rotate within the cluster) Maluti Cluster Taylor Bequest(Matatiele) Umzimvubu Cluster Madzikane kaZulu Hospital Mt.Ayliff Hospital Sipetu Hospital CACADU (Allocated professionals to rotate within the cluster This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za STAATSKOERANT, 16 OKTOBER 2013 No. 36936 115 Cambedoo Cluster Andries Vosloo Hospital Midlands Hospital Kouga Cluster Humansdorp Hospital Makana -

Health Professions Act: List of Approved Facilities for the Purposes

STAATSKOERANT, 16 OKTOBER 2013 No. 36936 39 No. 791 16 October 2013 HEALTH PROFESSIONS ACT, 1974 (ACT NO. 56 OF 1974) LIST OF APPROVED FACILITIES FOR THE PURPOSES OF PERFORMING COMMUNITY SERVICE BY MEDICAL PRACTITIONERS IN THE YEAR 2014 The Minister of Health has, in terms of regulation 5.1 of the Regulations relating to Performance of Community Service by Persons Registering in terms of the Health Professions Act, 1974 (Act No. 56 of 1974), listed the following approved facilities for purposes of the profession of medicine. PROVINCE REGION/DISTRICT FACILITY EASTERN CAPE Alfred Nzo Khotsong Hospital* Madzikane kaZulu Hospital ** Umzimvubu Cluster Mt Ayliff Hospital** Taylor Bequest Hospital* (Matatiele) Amathole Bhisho CHH Cathcart Hospital * Amahlathi/Buffalo City Cecilia Makiwane Hospital Cluster Dimbaza CHC Duncan Village Day Hospital Empilweni Gompo CHC Fort Grey TB Hospital Frere Hospital Grey Hospital * Komga Hospital Nkqubela TB Hospital Nompumelelo Hospital* SS Gida Hospital* Stutterheim FPA Hospital* Mnquma Sub-District Butterworth Hospital* Nqgamakwe CHC* Nkonkobe Sub-District Adelaide FPA Hospital Tower Hospital* Victoria Hospital * Mbashe /KSD District Elliotdale CHC* Idutywa CHC* Madwaleni Hospital* Chris Hani All Saints Hospital** Engcobo/IntsikaYethu Cofimvaba Hospital** Martjie Venter FPA Hospital This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za 40 No. 36936 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 16 OCTOBER 2013 Sub-District Mjanyana Hospital * InxubaYethembaSub-Cradock Hospital** Wilhelm Stahl Hospital** District Inkwanca -

JAMES BRECKINRIDGE by Katherine Kennedy Mcnulty Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute A

JAMES BRECKINRIDGE by Katherine Kennedy McNulty Thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF AR.TS in History APPROVED: Chairman: D~. George Green ShacJ;i'lford br. James I. Robertson, Jr. Dr. Weldon A. Brown July, 1970 Blacksburg, Virginia ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The writer wishes to thank many persons who were most helpful in the writing of this thesis. Special thanks are due Dr. George Green Shackelford whose suggestions and helpful corrections enabled the paper to progress from a rough draft to the finished state. of Roanoke, Virginia, was most generous in making available Breckinridge family papers and in showing t Grove Hill heirlooms. The writer also wishes to thank of the Roanoke Historical Society for the use of the B' Ln- ridge and Preston papers and for other courtesies, and of the Office of the Clerk of the Court of Botetourt County for his help with Botetourt Records and for sharing his knowledge of the county and the Breckinridge family. Recognition is also due the staffs of the Newman Library of V.P.I.S.U., the Alderman Library of the University of Virginia, the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress, and to the Military Department of the National Archives. Particular acknowledgment is made to the Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Virginia which made the award of its Graduate Fellowship in History at V.P.I.S.U. Lastly, the writer would like to thank her grandfather who has borne the cost of her education, and her husband who permitted her to remain in school and complete this degree. -

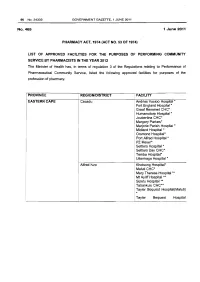

Health Professions Act: List of Approved Facilities for Community Service by Pharmacists in 2012

96 No.34332 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 1 JUNE 2011 No.465 1 June 2011 PHARMACY ACT, 1974 (ACT NO. 53 OF 1974} LIST OF APPROVED FACILITIES FOR THE PURPOSES OF PERFORMING COMMUNITY SERVICE BY PHARMACISTS IN THE YEAR 2012 The Minister of Health has, in terms of regulation 3 of the Regulations relating to Performance of Pharmaceutical Community Service, listed the following approved facilities for purposes of the profession of pharmacy. PROVINCE REGION/DISTRICT FACILITY EASTERN CAPE Cacadu Andries Vosloo Hospital * Fort England Hospital* Graaf Reneinet CHC* Humansdorp Hospital * Joubertina CHC* Margery Parkes* Marjorie Parish Hospital* Midland Hospital * Orsmond Hospital* Port Alfred Hospital * PZ Meyer* Settlers Hospital * Settlers Day CHC* Temba Hospital• Uitenhage Hospital * Alfred Nzo Khotsong Hospital• Maluti CHC* Mary Theresa Hospital .... ! Mt Ayliff Hospital ** · Sipetu Hospital •• Tabankulu CHC*• Tayler Bequest Hospitai(Maluti) * Tayler Bequest Hospital STAATSKOERANT, 1 JUNIE 2011 No. 34332 97 (Matatiele )"' Chris Hani All Saints Hospital ..... Cala Hospital ** Cofimvaba Hospital ** Cradock Hospital ** Elliot Hospital ... Frontier Hospital * Glen Grey Hospital * Mjanyana Hospital ** NgcoboCHC* Ngonyama CHC* Nomzamo CHC* Sada CHC* Thornhill CHC* Wilhelm Stahl Hospital ..... ZwelakheDalasile CHC* Nelson Mandala Dora Nginza Hospital Elizabeth Donkin Hospital Jose Pearson Santa Hospital Kwazakhele Day Clinic Laetitia Bam CH C Livingstone Hospital Motherwell CHC New Brighton CHC PE Pharmaceutical Depot PE Provincial Hospital Amathole Bedford Hospital Bhisho Hospital Butterworth Hospital Cecilia Makiwane Hospital Cathcart Hospital Dimbaza CHC Duncan Village Day CHC Dutywa CHC Empilweni Gompo CHC Fort Beauford Hospital Fort Grey Hospital Frere Hospital Grey Hospital Middledrift CHC Nontyatyambo CHC Nompomelelo Hospital Ngqamakwe CHC SS Gida Hospita Tafalofefe Hospital Tower Hospital Victoria Hospital Winterberg Hospital Willowvale CHC 98 No. -

Health Professions Act: List of Approved Facilities for Purposes Of

40 No. 35624 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 27 AUGUST 2012 No. 676 27 August 2012 HEALTH PROFESSIONS ACT, 1974 (ACT NO. 56 OF 1974) LIST OF APPROVED FACILITIES FOR THE PURPOSES OF PERFORMING COMMUNITY SERVICE BY MEDICAL PRACTITIONERS IN THE YEAR 2013 The Minister of Health has, in terms of regulation 5.1 of the Regulations relating to Performance of Community Service by Persons Registering in terms of the Health Professions Act, 1974 (Act No. 56 of 1974), listed the following facilities for purposes of the profession of medicine. PROVINCE REGION/DISTRICT FACILITY EASTERN CAPE Alfred Nzo Khotsong Hospital* Madzikane kaZulu Hospital ** Umzimvubu Cluster Mt Ayliff Hospital ** Taylor Bequest Hospital* (Matatiele) Amato le Cathcart Hospital * Cecilia Makiwane Hospital Amahlathi/Buffalo City Dimbaza CHC Cluster Fort Grey TB Hospital Grey Hospital * Komga Hospital Nkqubela TB Hospital Nompumelelo Hospital* SS Gida Hospital* Stutterheim FPA Hospital* Mnquma Sub-District Butterworth Hospital* Nqgamakhwe CHC* Nkonkobe Sub-District Adelaide FPA Hospital Tower Hospital* Victoria Hospital * Mbashe /KSD District Elliotdale CHC* Idutywa CHC* Madwaleni Hospital* Zitulele Hospital * Chris Hani All Saints Hospital ** Cofimvaba Hospital ** Engcobo/IntsikaYethu Martjie Venter FPA Hospital Sub-District Mjanyana Hospital * STAATSKOERANT, 27 AUGUSTUS 2012 No. 35624 41 lnxubaYethemba Sub-Cradock Hospital ** Wilhelm Stahl Hospital ** District Inkwanca Molteno FPA Hospital Lukhanji Frontier Hospital* Hewu Hospital * Komani Hospital* Sakhisizwe/Emalahleni Cala Hospital ** Dordrecht FPA Hospital Glen Grey Hospital ** Indwe FPA Hospital Ngonyama CHC* Nelson Mandela Metro Dora Nginza Hospital Empilweni TB Hospital PE Metro Jose Pearson TB Hospital Orsmond TB Hospital Letticia Barn CHC PE Provincial Uitenhage Hospital Kouga Sub-District Humansdorp Hospital BJ Voster FPA Hospital O.R.Tambo Dr Lizo Mpehle Memorial Hospital ** Nessie Knight Hospital ** Mhlontlo Sub-District Qaukeni North Sub-Greenville Hospital ** Holly Cross Hospital ** District Isipethu Hospital* Port St Johns CHC* St. -

Riding Uniforms of the Frontier Nursing Service Donna C

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® DLSC Faculty Publications Library Special Collections 1993 Made to Fit a Woman: Riding Uniforms of the Frontier Nursing Service Donna C. Parker Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/dlsc_fac_pub Part of the Archival Science Commons, Nursing Midwifery Commons, and the Public Health and Community Nursing Commons Recommended Repository Citation Parker, Donna C.. (1993). Made to Fit a Woman: Riding Uniforms of the Frontier Nursing Service. Dress, 20, 53-64. Available at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/dlsc_fac_pub/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in DLSC Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Made to Fit a Woman: Riding Uniforms of the Frontier Nursing Service 1 by Donna Parker The word “hello,” so familiar to all Frontier nurses, sounded under my window at Hyden and fetched me out to a midwifery case way over the mountain in the middle of a dark night. The man who came for me had no mule, and, as my patient had sent word for me to hurry, I left him behind with instructions to follow my trail. It is one of our few rules that no nurse rides alone at night, but I knew the man would never be far behind and we nurses are safe. Our uniform allows us to go anywhere in the mountains, and it is only fear of accident which prevents our riding alone at night. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SEN ATE·. of Athens; John Ulmer, F

1915. CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SEN ATE·. of Athens; John Ulmer, F. Pamperin, i.md other residents of By Mr. :MAGUIRE of Nebraska: Petition of sundry citizens Marshfield; Fred Kuhn, William F. Beyer, Rudolph Schlender, of Nebraska, favoring passage of Senate resolution 6683, rela Fred Knoke, August Miller, August Zietlow, F. W. Retzlaff, tive to export of munitions of war; to the Comll)ittee on For August Beversdorf, Rev. E. R. Kraeft, W. P. Nichols, Rev. E. C. eign Affairs. .T. Sterbenooll, Richard Tews, William Brown, Fred Grimm, By Mr. MAHAN: Petition of sundry citizens of Norwich, Ernst Kruger, l\Iartin Mussack, and o¢er residents of Shawano Conn., and vicinity, favoring House joint resolution 377, relative County; and William F. Becker, F. William Strohschoen, and to export of munitions of war; to the Committee on Foreign other residents of Marion, all in the State of Wisconsin, asking Affairs. that House joint resolution 377, which prohibits the export of By Mr. METZ: Memorial of Holy Name Society of Our Lady arms, ammunition, and munitions of war of every kind, be en of Lourdes parish, Brooklyn, and Brooklyn Diocesan Branch of acted into law; to the Committee on Foreign Affairs. the American Federation of Catholic Societies, and citizens of Bv Mr. BURKE of Wisconsin: Resolutions adopted by Home the tenth congressional district of New York, favoring legisla Order of Foresters, Court No. 1, of Sheboygan, Wis., and Schil tion to bar from the United States mails publications that ler Lodge, No. 68, Independent Order of Odd Fellows, of She slander the Catholic Church; to the Committee on the Post boygan, Wis., asking for the passage at this session of Congress Office and Post Roads.