Jihadi Commuters: How the Taleban Cross the Durand Line

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Progress in Afghanistan Bucharest Summit2-4 April 2008 Progress in Afghanistan

© MOD NL © MOD Canada © MOD Canada Progress in Afghanistan Progress in Bucharest Summit 2-4 April 2008 Bucharest Summit2-4 Progress in Afghanistan Contents page 1. Foreword by Assistant Secretary General for Public Diplomacy, ..........................1 Jean-François Bureau, and NATO Spokesman, James Appathurai 2. Executive summary .........................................................................................................................................2 3. Security ..................................................................................................................................................................... 4 • IED attacks and Counter-IED efforts 4 • Musa Qala 5 • Operations Medusa successes - Highlights Panjwayi and Zhari 6 • Afghan National Army 8 • Afghan National Police 10 • ISAF growth 10 4. Reconstruction and Development ............................................................................................... 12 • Snapshots of PRT activities 14 • Afghanistan’s aviation sector: taking off 16 • NATO-Japan Grant Assistance for Grassroots Projects 17 • ISAF Post-Operations Humanitarian Relief Fund 18 • Humanitarian Assistance - Winterisation 18 5. Governance ....................................................................................................................................................... 19 • Counter-Narcotics 20 © MOD Canada Foreword The NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) mission is approaching five years of operations in Afghanistan. This report is a -

NATO Airstrike Magnifies Political Divide Over the War in Afghanistan

Nxxx,2009-09-05,A,009,Bs-BW,E3 THE NEW YORK TIMES INTERNATIONAL SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 5, 2009 ØØN A9 NATO Airstrike Magnifies Political Divide Over the War in Afghanistan governor of Ali Abad, Hajji Habi- From Page A1 bullah, said the area was con- with the Afghan people.” trolled by Taliban commanders. Two 14-year-old boys and one The Kunduz area was once 10-year-old boy were admitted to calm, but much of it has recently the regional hospital here in Kun- slipped under the control of in- duz, along with a 16-year-old who surgents at a time when the Oba- later died. Mahboubullah Sayedi, ma administration has sent thou- a spokesman for the Kunduz pro- sands of more troops to other vincial governor, said most of the parts of the country to combat an estimated 90 dead were militants, insurgency that continues to gain judging by the number of charred strength in many areas. pieces of Kalashnikov rifles The region is patrolled mainly found. But he said civilians were by NATO’s 4,000-member Ger- also killed. man force, which is barred by In explaining the civilian German leaders from operating deaths, military officials specu- in combat zones farther south. lated that local people were con- The United States has 68,000 scripted by the Taliban to unload troops in Afghanistan, more than the fuel from the tankers, which any other nation; other countries were stuck near a river several fighting under the NATO com- miles from the nearest villages. mand have a combined total of about 40,000 troops here. -

SDN Changes 2014

OFFICE OF FOREIGN ASSETS CONTROL CHANGES TO THE Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List SINCE JANUARY 1, 2014 This publication of Treasury's Office of Foreign AL TOKHI, Qari Saifullah (a.k.a. SAHAB, Qari; IN TUNISIA; a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARIA IN Assets Control ("OFAC") is designed as a a.k.a. SAIFULLAH, Qari), Quetta, Pakistan; DOB TUNISIA; a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARI'AH; a.k.a. reference tool providing actual notice of actions by 1964; alt. DOB 1963 to 1965; POB Daraz ANSAR AL-SHARI'AH IN TUNISIA; a.k.a. OFAC with respect to Specially Designated Jaldak, Qalat District, Zabul Province, "SUPPORTERS OF ISLAMIC LAW"), Tunisia Nationals and other entities whose property is Afghanistan; citizen Afghanistan (individual) [FTO] [SDGT]. blocked, to assist the public in complying with the [SDGT]. AL-RAYA ESTABLISHMENT FOR MEDIA various sanctions programs administered by SAHAB, Qari (a.k.a. AL TOKHI, Qari Saifullah; PRODUCTION (a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARIA; OFAC. The latest changes may appear here prior a.k.a. SAIFULLAH, Qari), Quetta, Pakistan; DOB a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARI'A BRIGADE; a.k.a. to their publication in the Federal Register, and it 1964; alt. DOB 1963 to 1965; POB Daraz ANSAR AL-SHARI'A IN BENGHAZI; a.k.a. is intended that users rely on changes indicated in Jaldak, Qalat District, Zabul Province, ANSAR AL-SHARIA IN LIBYA; a.k.a. ANSAR this document that post-date the most recent Afghanistan; citizen Afghanistan (individual) AL-SHARIAH; a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARIAH Federal Register publication with respect to a [SDGT]. -

CB Meeting PAK/AFG

Polio Eradication Initiative Afghanistan Current Situation of Polio Eradication in Afghanistan Independent Monitoring Board Meeting 29-30 April 2015,Abu Dhabi AFP cases Classification, Afghanistan Year 2013 2014 2015 Reported AFP 1897 2,421 867 cases Confirmed 14 28 1 Compatible 4 6 0 VDPV2 3 0 0 Discarded 1876 2,387 717 Pending 0 0 *149 Total of 2,421 AFP cases reported in 2014 and 28 among them were confirmed Polio while 6 labelled* 123as Adequatecompatible AFP cases Poliopending lab results 26 Inadequate AFP cases pending ERC 21There Apr 2015 is one Polio case reported in 2015 as of 21 April 2015. Region wise Wild Poliovirus Cases 2013-2014-2015, Afghanistan Confirmed cases Region 2013 2014 2015 Central 1 0 0 East 12 6 0 2013 South east 0 4 0 Districts= 10 WPV=14 South 1 17 1 North 0 0 0 Northeast 0 0 0 West 0 1 0 Polio cases increased by 100% in 2014 Country 14 28 1 compared to 2013. Infected districts increased 2014 District= 19 from 10 to 19 in 2014. WPV=28 28 There30 is a case surge in Southern Region while the 25Eastern Region halved the number of cases20 in comparison14 to 2013 Most15 of the infected districts were in South, East10 and South East region in 2014. No of AFP cases AFP of No 1 2015 5 Helmand province reported a case in 2015 District= 01 WPV=01 after0 a period of almost two months indicates 13 14 15 Year 21continuation Apr 2015 of low level circulation. Non Infected Districts Infected Districts Characteristics of polio cases 2014, Afghanistan • All the cases are of WPV1 type, 17/28 (60%) cases are reported from Southern region( Kandahar-13, Helmand-02, and 1 each from Uruzgan and Zabul Province). -

Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces

European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9485-650-0 doi: 10.2847/115002 BZ-02-20-565-EN-N © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2020 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Al Jazeera English, Helmand, Afghanistan 3 November 2012, url CC BY-SA 2.0 Taliban On the Doorstep: Afghan soldiers from 215 Corps take aim at Taliban insurgents. 4 — AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY FORCES - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT Acknowledgements This report was drafted by the European Asylum Support Office COI Sector. The following national asylum and migration department contributed by reviewing this report: The Netherlands, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis, Ministry of Justice It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, it but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY -

Environment Scan: 01-15 Dec 2017 China

ENVIRONMENT SCAN: 01-15 DEC 2017 CHINA (Geo-Strat, Geo-Politics & Geo Economics) Brig Rajeev Kumar Bhutani (Retd) World Political Parties Dialogue Concludes with ‘Beijing Initiative’. One of the biggest meetings of global political parties wrapped-up in Beijing on 3 December 2017. It was the first major multilateral diplomacy event hosted by China after the recently concluded 19th CPC National Congress. It was also the first time the CPC held a high-level meeting with such a wide range of political parties from around the world. Over 600 delegates representing nearly 300 political parties and political organizations from over 120 countries attended the meeting.The meeting was officially reported to be a complete success with a broad consensus reached. Year end - China Focus: From Follower to Leader: China Emerges at High-Tech Frontier. After years of focusing on innovation, China has caught up fast. Silicon Valley has long been considered the most viable option for starting a business in the tech sector. Now, this is beginning to change. Known as "sea turtles," a growing number of overseas-educated Chinese are returning to their home country, turning down opportunities in Silicon Valley to make a splash in China's emerging tech sector. As the number of Chinese students at overseas universities surged to 544,500 in 2016, the number of sea turtles also surged, with 432,500 returning to China last year, nearly 60 percent more than 2012, according to the Ministry of Education. The reverse brain drain has benefited China's tech companies. A brilliant example is Royole, a company founded in 2012 by "sea turtle" Liu Zihong, a Stanford graduate. -

Winning Hearts and Minds in Uruzgan Province by Paul Fishstein ©2012 Feinstein International Center

AUGUST 2012 Strengthening the humanity and dignity of people in crisis through knowledge and practice BRIEFING NOTE: Winning Hearts and Minds in Uruzgan Province by Paul Fishstein ©2012 Feinstein International Center. All Rights Reserved. Fair use of this copyrighted material includes its use for non-commercial educational purposes, such as teaching, scholarship, research, criticism, commentary, and news reporting. Unless otherwise noted, those who wish to reproduce text and image fi les from this publication for such uses may do so without the Feinstein International Center’s express permission. However, all commercial use of this material and/or reproduction that alters its meaning or intent, without the express permission of the Feinstein International Center, is prohibited. Feinstein International Center Tufts University 114 Curtis Street Somerville, MA 02144 USA tel: +1 617.627.3423 fax: +1 617.627.3428 fi c.tufts.edu 2 Feinstein International Center Contents I. Summary . 4 II. Study Background . 5 III. Uruzgan Province . 6 A. Geography . 6 B. Short political history of Uruzgan Province . 6 C. The international aid, military, and diplomatic presence in Uruzgan . 7 IV. Findings . .10 A. Confl uence of governance and ethnic factors . .10 B. International military forces . .11 C. Poor distribution and corruption in aid projects . .12 D. Poverty and unemployment . .13 E. Destabilizing effects of aid projects . 14 F. Winning hearts and minds? . .15 V. Final Thoughts and Looking Ahead . .17 Winning Hearts and Minds in Uruzgan Province 3 I. SUMMARY esearch in Uruzgan suggests that insecurity is largely the result of the failure Rof governance, which has exacerbated traditional tribal rivalries. -

2. AFGHANISTAN Stalled Peace Process Under Threat

IRC WATCHLIST 2021 16 IRC WATCHLIST 2021 17 2. AFGHANISTAN Stalled peace process under threat KEY FACTS PROBABILITY IMPACT CONSTRAINTS ON HUMAN THREAT Population: 38.9 million 10 8 COUNTRY RESPONSE EXISTING PRESSURES NATURAL THREAT 18.4 million people in need of humanitarian aid 7 9 ON POPULATION 16.9 million people facing crisis or worse levels of food insecurity (IPC 3+) Afghanistan has risen to second on Watchlist because of its high exposure to the triple threats of conflict, COVID-19 and 3 million people internally displaced due to conflict climate change and uncertainty over the stalled peace process and violence between the government and the Taliban. 1.2 million IDPs due to natural disasters Even after four decades of crises, humanitarian needs in Afghanistan are growing rapidly amid COVID-19 and unrelenting violence, with the 2.8 million Afghan refugees number of people in need for 2021 nearly doubling compared to early 2020. Needs could rise rapidly in 2021 if intra-Afghan peace talks fail 6,000 civilian casualties in the first three quarters of to make progress, particularly amid uncertainty about the continued 2020 US military presence in the country. The global pandemic and climate- related disasters are exacerbating needs for Afghans, many of whom 130th (of 195 countries) for capability to prevent and have lived through decades of conflict, chronic poverty, economic crises, mitigate epidemics and protracted displacement. Some armed groups oppose the peace talks and so the security situation in Afghanistan will remain volatile 50.8% of women over 15 report they have ever experi- regardless of that process, with violence continuing to drive humanitarian enced physical and/or sexual violence from an intimate needs and civilian casualties. -

AFGHANISTAN Weekly Humanitarian Update (12 – 18 July 2021)

AFGHANISTAN Weekly Humanitarian Update (12 – 18 July 2021) KEY FIGURES IDPs IN 2021 (AS OF 18 JULY) 294,703 People displaced by conflict (verified) 152,387 Received assistance (including 2020 caseload) NATURAL DISASTERS IN 2021 (AS OF 11 JULY) 24,073 Number of people affected by natural disasters Conflict incident RETURNEES IN 2021 Internal displacement (AS OF 18 JULY) 621,856 Disruption of services Returnees from Iran 7,251 Returnees from Pakistan 45 South: Fighting continues including near border Returnees from other Kandahar and Hilmand province witnessed a significant spike in conflict during countries the reporting period. A Non-State Armed Group (NSAG) reportedly continued to HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE apply pressure on District Administrative Centres (DACs) and provincial capitals PLAN (HRP) REQUIREMENTS & to expand areas under their control while Afghan National Security Forces FUNDING (ANSF) conducted clearing operations supported by airstrikes. Ongoing conflict reportedly led to the displacement of civilians with increased fighting resulting in 1.28B civilian casualties in Dand and Zheray districts in Kandahar province and Requirements (US$) – HRP Lashkargah city in Hilmand province. 2021 The intermittent closure of roads to/from districts and provinces, particularly in 479.3M Hilmand and Kandahar provinces, hindered civilian movements and 37% funded (US$) in 2021 transportation of food items and humanitarian/medical supplies. Intermittent AFGHANISTAN HUMANITARIAN outages of mobile service continued. On 14 July, an NSAG reportedly took FUND (AHF) 2021 control of posts and bases around the Spin Boldak DAC and Wesh crossing between Afghanistan and Pakistan. Closure of the border could affect trade and 43.61M have adverse implications on local communities and the region. -

The First Six Months GR&D

Governance, Reconstruction, Jan 15, GR&D & Development 2010 Interim Report: The First Six Months GR&D Governance, Reconstruction, & Development “What then should the objective be for this war? The aim needs to be to build an administrative and judicial infrastructure that will deliver security and stability to the population and, as a result, marginalize the Taliban. Simultaneously, it can create the foundations for a modern nation.” -Professor Akbar S. Ahmed Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies American University Cover Captions (clockwise): Afghan children watch US Soldiers from 2nd Battalion, 1st Infantry Regiment, 5th Brigade, 2nd Infantry Di- vision conduct a dismounted patrol through the village of Pir Zadeh, Dec. 3, 2009. (US Air Force photo by Staff Sgt. Dayton Mitchell) US Soldiers from 4th Battalion, 23rd Infantry Regiment, 5th Brigade, 2nd Infantry Division conduct a joint patrol with Afghan National Army soldiers and Afghan National Policemen in Shabila Kalan Village, Zabul Prov- ince, Nov. 30, 2009. (US Air Force photo by Tech. Sgt. Efren Lopez) An Afghan elder speaks during a shura at the Arghandab Joint District Community Center, Dec. 03, 2009. (US Air Force photo by Tech. Sgt. Francisco V. Govea II) An Afghan girl awaits to receive clothing from US Soldiers from 4th Battalion, 23rd Infantry Regiment, Boragay Village, Zabul Province, Afghanistan, Dec. 4, 2009. US Soldiers are conducting a humanitarian relief project , "Bundle-up,” providing Afghan children with shoes, jackets, blankets, scarves, and caps. (US Air Force -

The Afghanistan-Pakistan Wars, 2008–2009: Micro-Geographies, Conflict Diffusion, and Clusters of Violence

The Afghanistan-Pakistan Wars, 2008–2009: Micro-geographies, Conflict Diffusion, and Clusters of Violence John O’Loughlin, Frank D. W. Witmer, and Andrew M. Linke1 Abstract: A team of political geographers analyzes over 5,000 violent events collected from media reports for the Afghanistan and Pakistan conflicts during 2008 and 2009. The violent events are geocoded to precise locations and the authors employ an exploratory spatial data analysis approach to examine the recent dynamics of the wars. By mapping the violence and examining its temporal dimensions, the authors explain its diffusion from traditional foci along the border between the two countries. While violence is still overwhelmingly concentrated in the Pashtun regions in both countries, recent policy shifts by the American and Pakistani gov- ernments in the conduct of the war are reflected in a sizeable increase in overall violence and its geographic spread to key cities. The authors identify and map the clusters (hotspots) of con- flict where the violence is significantly higher than expected and examine their shifts over the two-year period. Special attention is paid to the targeting strategy of drone missile strikes and the increase in their number and geographic extent by the Obama administration. Journal of Economic Literature, Classification Numbers: H560, H770, O180. 15 figures, 1 table, 113 ref- erences. Key words: Afghanistan, Pakistan, Taliban, Al- Qaeda, insurgency, Islamic terrorism, U.S. military, International Security Assistance Forces, Durand Line, Tribal Areas, Northwest Frontier Province, ACLED, NATO. merica’s “longest war” is now (August 2010) nearing its ninth anniversary. It was Alaunched in October 2001 as a “war of necessity” (Barack Obama, August 17, 2009) to remove the Taliban from power in Afghanistan, and thus remove the support of this regime for Al-Qaeda, the terrorist organization that carried out the September 2001 attacks in the United States. -

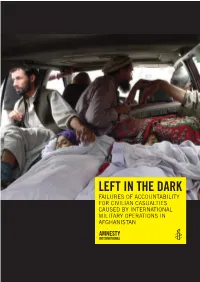

Left in the Dark

LEFT IN THE DARK FAILURES OF ACCOUNTABILITY FOR CIVILIAN CASUALTIES CAUSED BY INTERNATIONAL MILITARY OPERATIONS IN AFGHANISTAN Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2014 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2014 Index: ASA 11/006/2014 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Bodies of women who were killed in a September 2012 US airstrike are brought to a hospital in the Alingar district of Laghman province. © ASSOCIATED PRESS/Khalid Khan amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP OF AFGHANISTAN .......................................................................................... 6 1. SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 7 Methodology ..........................................................................................................