Read CIMAM's 2018 Conference Proceedings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HEBEELE, Gerald Clarence, 1932- the PREDICAMENT of the BRITISH UNIONIST PARTY, 1906-1914

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 68-3000 HEBEELE, Gerald Clarence, 1932- THE PREDICAMENT OF THE BRITISH UNIONIST PARTY, 1906-1914. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1967 History, modem University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan © Copyright by Gerald Clarence Heberle 1968 THE PREDICAMENT OF THE BRITISH UNIONIST PARTY, 1906-1914 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Gerald c / Heberle, B.A., M.A, ******* The Ohio State University 1967 Approved by B k f y f ’ P c M k ^ . f Adviser Department of History ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to express my deepest gratitude to Professor Philip P. Poirier of the Department of History, The Ohio State University, Dr. Poirier*s invaluable advice, his unfailing patience, and his timely encouragement were of immense assistance to me in the production of this dissertation, I must acknowledge the splendid service of the staff of the British Museum Manuscripts Room, The Librarian and staff of the University of Birmingham Library made the Chamberlain Papers available to me and were most friendly and helpful. His Lordship, Viscount Chilston, and Dr, Felix Hull, Kent County Archivist, very kindly permitted me to see the Chilston Papers, I received permission to see the Asquith Papers from Mr, Mark Bonham Carter, and the Papers were made available to me by the staff of the Bodleian Library, Oxford University, To all of these people I am indebted, I am especially grateful to Mr, Geoffrey D,M, Block and to Miss Anne Allason of the Conservative Research Department Library, Their cooperation made possible my work in the Conservative Party's publications, and their extreme kindness made it most enjoyable. -

One Hundred Years of Thomism Aeterni Patris and Afterwards a Symposium

One Hundred Years of Thomism Aeterni Patris and Afterwards A Symposium Edited By Victor B. Brezik, C.S.B, CENTER FOR THOMISTIC STUDIES University of St. Thomas Houston, Texas 77006 ~ NIHIL OBSTAT: ReverendJamesK. Contents Farge, C.S.B. Censor Deputatus INTRODUCTION . 1 IMPRIMATUR: LOOKING AT THE PAST . 5 Most Reverend John L. Morkovsky, S.T.D. A Remembrance Of Pope Leo XIII: The Encyclical Aeterni Patris, Leonard E. Boyle,O.P. 7 Bishop of Galveston-Houston Commentary, James A. Weisheipl, O.P. ..23 January 6, 1981 The Legacy Of Etienne Gilson, Armand A. Maurer,C.S.B . .28 The Legacy Of Jacques Maritain, Christian Philosopher, First Printing: April 1981 Donald A. Gallagher. .45 LOOKING AT THE PRESENT. .61 Copyright©1981 by The Center For Thomistic Studies Reflections On Christian Philosophy, All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or Ralph McInerny . .63 reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written Thomism And Today's Crisis In Moral Values, Michael permission, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in Bertram Crowe . .74 critical articles and reviews. For information, write to The Transcendental Thomism, A Critical Assessment, Center For Thomistic Studies, 3812 Montrose Boulevard, Robert J. Henle, S.J. 90 Houston, Texas 77006. LOOKING AT THE FUTURE. .117 Library of Congress catalog card number: 80-70377 Can St. Thomas Speak To The Modem World?, Leo Sweeney, S.J. .119 The Future Of Thomistic Metaphysics, ISBN 0-9605456-0-3 Joseph Owens, C.Ss.R. .142 EPILOGUE. .163 The New Center And The Intellectualism Of St. Thomas, Printed in the United States of America Vernon J. -

National Arts Awards Monday, October 19, 2015

2015 Americans for the Arts National Arts Awards Monday, October 19, 2015 Welcome from Robert L. Lynch Performance by YoungArts Alumni President and CEO of Americans for the Arts Musical Director, Jake Goldbas Philanthropy in the Arts Award Legacy Award Joan and Irwin Jacobs Maria Arena Bell Presented by Christopher Ashley Presented by Jeff Koons Outstanding Contributions to the Arts Award Young Artist Award Herbie Hancock Lady Gaga 1 Presented by Paul Simon Presented by Klaus Biesenbach Arts Education Award Carolyn Clark Powers Alice Walton Lifetime Achievement Award Presented by Agnes Gund Sophia Loren Presented by Rob Marshall Dinner Closing Remarks Remarks by Robert L. Lynch and Abel Lopez, Chair, introduction of Carolyn Clark Powers Americans for the Arts Board of Directors and Robert L. Lynch Remarks by Carolyn Clark Powers Chair, National Arts Awards Greetings from the Board Chair and President Welcome to the 2015 National Arts Awards as Americans for the Arts celebrates its 55th year of advancing the arts and arts education throughout the nation. This year marks another milestone as it is also the 50th anniversary of President Johnson’s signing of the act that created America’s two federal cultural agencies: the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities. Americans for the Arts was there behind the scenes at the beginning and continues as the chief advocate for federal, state, and local support for the arts including the annual NEA budget. Each year with your help we make the case for the funding that fuels creativity and innovation in communities across the United States. -

Dlkj;Fdslk ;Lkfdj

MoMA PRESENTS SCREENINGS OF VIDEO ART AND INTERVIEWS WITH WOMEN ARTISTS FROM THE ARCHIVE OF THE VIDEO DATA BANK Video Art Works by Laurie Anderson, Miranda July, and Yvonne Rainer and Interviews With Artists Such As Louise Bourgeois and Lee Krasner Are Presented FEEDBACK: THE VIDEO DATA BANK, VIDEO ART, AND ARTIST INTERVIEWS January 25–31, 2007 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters NEW YORK, January 9, 2007— The Museum of Modern Art presents Feedback: The Video Data Bank, Video Art, and Artist Interviews, an exhibition of video art and interviews with female visual and moving-image artists drawn from the Chicago-based Video Data Bank (VDB). The exhibition is presented January 25–31, 2007, in The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters, on the occasion of the publication of Feedback, The Video Data Bank Catalog of Video Art and Artist Interviews and the presentation of MoMA’s The Feminist Future symposium (January 26 and 27, 2007). Eleven programs of short and longer-form works are included, including interviews with artists such as Lee Krasner and Louise Bourgeois, as well as with critics, academics, and other commentators. The exhibition is organized by Sally Berger, Assistant Curator, Department of Film, The Museum of Modern Art, with Blithe Riley, Editor and Project Coordinator, On Art and Artists collection, Video Data Bank. The Video Data Bank was established in 1976 at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago as a collection of student productions and interviews with visiting artists. During the same period in the mid-1970s, VDB codirectors Lyn Blumenthal and Kate Horsfield began conducting their own interviews with women artists who they felt were underrepresented critically in the art world. -

Tate Report 2010-11: List of Tate Archive Accessions

Tate Report 10–11 Tate Tate Report 10 –11 It is the exceptional generosity and vision If you would like to find out more about Published 2011 by of individuals, corporations and numerous how you can become involved and help order of the Tate Trustees by Tate private foundations and public-sector bodies support Tate, please contact us at: Publishing, a division of Tate Enterprises that has helped Tate to become what it is Ltd, Millbank, London SW1P 4RG today and enabled us to: Development Office www.tate.org.uk/publishing Tate Offer innovative, landmark exhibitions Millbank © Tate 2011 and Collection displays London SW1P 4RG ISBN 978-1-84976-044-7 Tel +44 (0)20 7887 4900 Develop imaginative learning programmes Fax +44 (0)20 7887 8738 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Strengthen and extend the range of our American Patrons of Tate Collection, and conserve and care for it Every effort has been made to locate the 520 West 27 Street Unit 404 copyright owners of images included in New York, NY 10001 Advance innovative scholarship and research this report and to meet their requirements. USA The publishers apologise for any Tel +1 212 643 2818 Ensure that our galleries are accessible and omissions, which they will be pleased Fax +1 212 643 1001 continue to meet the needs of our visitors. to rectify at the earliest opportunity. Or visit us at Produced, written and edited by www.tate.org.uk/support Helen Beeckmans, Oliver Bennett, Lee Cheshire, Ruth Findlay, Masina Frost, Tate Directors serving in 2010-11 Celeste -

The Game of War, MW-Spring 2008

The Game of War: Debord as Strategist By McKenzie Wark for Issue 29 Sloth Spring 2008 The only member of the Situationist International to remain at its dissolution in 1972 was Guy Debord (1931–1994). He is often held to be synonymous with the movement, but anti- Debordist accounts rightly stress the role of others, such as Asger Jorn (1914–1973) or Constant Nieuwenhuys (1920–2005) who both left the movement as it headed out of its “aesthetic” phase towards its ostensibly more “political” one. Take, for example, Constant’s extraordinary New Babylon project, which he began while a member of the Situationist International and continued independently after separating from it. Constant imagined an entirely new landscape for the earth, one devoted entirely to play. But New Babylon is a landscape that began from the premise that the transition to this new landscape is a secondary problem. Play is one of the key categories of Situationist thought and practice, but would it really be possible to bring this new landscape for play into being entirely by means of play itself? This is the locus where the work of Constant and Debord might be brought back into some kind of relation to each other, despite their personal and organizational estrangement in 1960. Constant offered the kinds of landscape that the Situationists experiments might conceivably bring about. It was Debord who proposed an architecture for investigating the strategic potential escaping from the existing landscape of overdeveloped or spectacular society. Between the two possibilities lies the situation. Debord is best known as the author of The Society of the Spectacle (1967), but in many ways it is not quite a representative text. -

Newsletter 2009

NEWSLETTER 2009 NEWSLETTER CONTENTS 2 Letter from the Chair and President, Board of Trustees Skowhegan, an intensive 3 Letter from the Chair, Board of Governors nine-week summer 4 Trustee Spotlight: Ann Gund residency program for 7 Governor Spotlight: David Reed 11 Alumni Remember Skowhegan emerging visual artists, 14 Letters from the Executive Directors seeks each year to bring 16 Campus Connection 18 2009 Awards Dinner together a gifted and 20 2010 Faculty diverse group of individuals 26 Skowhegan Council & Alliance 28 Alumni News to create the most stimulating and rigorous environment possible for a concentrated period of artistic creation, interaction, and growth. FROM THE CHAIR & PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES FROM THE CHAIR OF THE BOARD OF GOVERNORS ANN L. GUND Chair / GREGORY K. PALM President BYRON KIM (’86) We write to you following another wonderful Trustees’/ featuring a talk by the artist and in June for a visit leadership. We will miss her, but know she will bring Many years ago, the founders of the Skowhegan great food for thought as we think about the shape a Governors’ Weekend on Skowhegan’s Maine campus, to Skowhegan Trustee George Ahl’s eclectic and her wisdom and experience to bear in the New York School of Painting & Sculpture formed two distinct new media lab should take. where we always welcome the opportunity to see beautiful collection which includes several Skowhegan Arts Program of Ohio Wesleyan University, where governing bodies that have worked strongly together to As with our participants, we are committed to diversity the School’s program in action and to meet the artists. -

Dara Birnbaum

DARA BIRNBAUM 8 NOVEMBER 201 8 – 12 JANUARY, 2019 OPENING RECEPTION: THURSDAY 8 NOVEMBER 2018 , 6– 8pm “Her use of video and found footage, her editing and image processing are groundbreaking…. This is our visual language.” -Eva Respini, Barbara Lee Chief Curator, ICA, Boston Marian Goodman Gallery London is delighted to present an exhibition of works by Dara Birnbaum, with special focus on her large-scale video installations from the 1990s. The exhibition will open on 8 November 2018, running until 12 January 2019. Birnbaum’s practice has long been concerned with the lexicon of broadcasting and communication and the way ‘truths’ are delivered to the viewer. An early proponent of video art, Birnbaum began by isolating imagery from television, recontextualising it in an attempt to understand its true meaning. For the first time since her major 2009/2010 travelling retrospective, The Dark Matter of Media Light, the three works Tiananmen Square: Break-In Transmission, 1990, Transmission Tower: Sentinel, 1992 and Hostage, 1994, will be shown Transmission Tower: Sentinel, 1992. Installation view, together. All three pieces were made in response to major political events in the latter part of Documenta IX commission, Kassel, Germany, 1992. the 20th century, as a way to uncover the complex relationship between the media, the events covered and the way in which those events are presented to the public. On view in the side galleries will be a selection of two-dimensional works focusing on the anonymous street posters from the May 68 protests in France, as well as the series Lesson Plans (To Keep the Revolution Alive), 1977, which formed the basis of the artist’s first exhibition, at Artists Space in New York in 1977. -

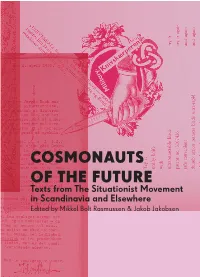

Cosmonauts of the Future: Texts from the Situationist

COSMONAUTS OF THE FUTURE Texts from The Situationist Movement in Scandinavia and Elsewhere Edited by Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Jakob Jakobsen 1 COSMONAUTS OF THE FUTURE 2 COSMONAUTS OF THE FUTURE Texts from the Situationist Movement in Scandinavia and Elsewhere 3 COSMONAUTS OF THE FUTURE TEXTS FROM THE SITUATIONIST MOVEMENT IN SCANDINAVIA AND ELSEWHERE Edited by Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Jakob Jakobsen COSMONAUTS OF THE FUTURE Published 2015 by Nebula in association with Autonomedia Nebula Autonomedia TEXTS FROM THE SITUATIONIST Læssøegade 3,4 PO Box 568, Williamsburgh Station DK-2200 Copenhagen Brooklyn, NY 11211-0568 Denmark USA MOVEMENT IN SCANDINAVIA www.nebulabooks.dk www.autonomedia.org [email protected] [email protected] AND ELSEWHERE Tel/Fax: 718-963-2603 ISBN 978-87-993651-8-0 ISBN 978-1-57027-304-9 Edited by Editors: Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Jakob Jakobsen | Translators: Peter Shield, James Manley, Anja Büchele, Matthew Hyland, Fabian Tompsett, Jakob Jakobsen | Copyeditor: Marina Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen Vishmidt | Proofreading: Danny Hayward | Design: Åse Eg |Printed by: Naryana Press in 1,200 copies & Jakob Jakobsen Thanks to: Jacqueline de Jong, Lis Zwick, Ulla Borchenius, Fabian Tompsett, Howard Slater, Peter Shield, James Manley, Anja Büchele, Matthew Hyland, Danny Hayward, Marina Vishmidt, Stevphen Shukaitis, Jim Fleming, Mathias Kokholm, Lukas Haberkorn, Keith Towndrow, Åse Eg and Infopool (www.scansitu.antipool.org.uk) All texts by Jorn are © Donation Jorn, Silkeborg Asger Jorn: “Luck and Change”, “The Natural Order” and “Value and Economy”. Reprinted by permission of the publishers from The Natural Order and Other Texts translated by Peter Shield (Farnham: Ashgate, 2002), pp. 9-46, 121-146, 235-245, 248-263. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Wednesday, October 14, 2020

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Wednesday, October 14, 2020 MOCA FORMS ENVIRONMENTAL COUNCIL A FIRST FOR A MAJOR U.S. ART MUSEUM The Aileen Getty Plaza at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. LOS ANGELES—The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) announces the creation of an Environmental Council, the first for a major art museum in the United States. The Council is focused on climate, conservation, and environmental justice in furtherance of the museum’s mission. In development since Klaus Biesenbach became the Director of MOCA in 2018, the museum will unfold important initiatives made possible by the Council within the first year, including financial commitments and expertise to work toward institution-wide carbon negativity, carbon- free energy, environmentally-focused museum quality exhibitions, educational programming, related artist support, and reductions in emissions and consumption. MOCA plans to publicly share the Council’s efforts and progress as a platform for public dialogue and engagement on this urgent topic. MOCA Environmental Council Founders and Co-Chairs are David Johnson and Haley Mellin. Founding Council members are Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Aileen Getty, Agnes Gund, Sheikha Al Mayassa Bint Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani and Brian Sheth. Expert advisors to the Council include Illina Frankiv, Dan Hammer, Lisa P. Jackson, Lucas Joppa, Jen Morris, Calla Rose Ostrander and Enrique Ortiz. MOCA Executive Director, Klaus Biesenbach, and MOCA Deputy Director, Advancement, Samuel Vasquez will be ex-officio members of the Council and assure continuity and communication between the Council’s priorities and the museum’s activities and operations. The Council will support artists working on critical environmental issues by financially supporting meaningful exhibition and educational programming. -

VISITOR FIGURES 2015 the Grand Totals: Exhibition and Museum Attendance Numbers Worldwide

SPECIAL REPORT VISITOR FIGURES2015 The grand totals: exhibition and museum attendance numbers worldwide VISITOR FIGURES 2015 The grand totals: exhibition and museum attendance numbers worldwide THE DIRECTORS THE ARTISTS They tell us about their unlikely Six artists on the exhibitions blockbusters and surprise flops that made their careers U. ALLEMANDI & CO. PUBLISHING LTD. EVENTS, POLITICS AND ECONOMICS MONTHLY. EST. 1983, VOL. XXV, NO. 278, APRIL 2016 II THE ART NEWSPAPER SPECIAL REPORT Number 278, April 2016 SPECIAL REPORT VISITOR FIGURES 2015 Exhibition & museum attendance survey JEFF KOONS is the toast of Paris and Bilbao But Taipei tops our annual attendance survey, with a show of works by the 20th-century artist Chen Cheng-po atisse cut-outs in New attracted more than 9,500 visitors a day to Rio de York, Monet land- Janeiro’s Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil. Despite scapes in Tokyo and Brazil’s economic crisis, the deep-pocketed bank’s Picasso paintings in foundation continued to organise high-profile, free Rio de Janeiro were exhibitions. Works by Kandinsky from the State overshadowed in 2015 Russian Museum in St Petersburg also packed the by attendance at nine punters in Brasilia, Rio, São Paulo and Belo Hori- shows organised by the zonte; more than one million people saw the show National Palace Museum in Taipei. The eclectic on its Brazilian tour. Mgroup of exhibitions topped our annual survey Bernard Arnault’s new Fondation Louis Vuitton despite the fact that the Taiwanese national muse- used its ample resources to organise a loan show um’s total attendance fell slightly during its 90th that any public museum would envy. -

Gary Hume CV

Gary Hume Born in 1962, Kent, UK Lives and works in London, UK and New York, USA EDUCATION 1988 Goldsmiths College, London, UK SELECTED SOLO SHOW 2019 Matthew Marks Gallery, Los Angeles, USA Carvings, New Art Centre, Salisbury, UK Looking and Seeing, Barakat Contemporary, Seoul, Korea Destroyed School Paintings, Matthew Marks Gallery, New York. Traveled to Museum Dhondt- Dhaenens, Deurle, Belgium (catalogue) 2018 Sprüth Magers, Berlin, Germany 2017 RA: Prints Pictures, Royal Academy of Arts, London, UK Mum, Sprüth Magers, London, UK (catalogue) Mum, Matthew Marks Gallery, New York, USA (catalogue) 2016 Front of a Snowman, Aspen Art Museum, Aspen, USA 2014 Lions and Unicorns, White Cube Gallery, São Paulo, Brazil 2013 The Wonky Wheel, Matthew Marks Gallery, New York, USA (catalogue) White Cube, London, UK Tate Britain, London, UK (catalogue) 2012 2, Sprüth Magers, Berlin, Germany Anxiety and the Horse, Matthew Marks Gallery, New York, USA The Indifferent Owl, White Cube, London, UK (catalogue) Beauty, Pinchuk Art Centre, Kiev, Ukraine Flashback, Leeds Art Gallery, UK. Traveled to Wolverhampton Art Gallery, UK; Jerwood Gallery, Hastings, UK; and Aberdeen Art Gallery, UK (catalogue) 2010 Bird in a Fishtank, Sprüth Magers, Berlin, Germany BARAKAT CONTEMPORARY 36, Samcheong–ro 7–gil, Jongno–gu [email protected] +82 02 730 1948 barakatcontemporary.com New Work, New Art Centre, Roche Court, East Winterslow, UK 2009 Yardwork, Matthew Marks Gallery, New York, USA (catalogue) 2008 Door Paintings, Modern Art Oxford, UK (catalogue) Baby Birds