Executivesfcomm00raabrich.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Duncan's American Radio, Inc. May 1985

AMERICAN RADIO WINTER 1985 SUPPLEMENT Compiled and edited by: JAMES H. DUNCAN, JR. DUNCAN'S AMERICAN RADIO, INC. BOX 2966 KALAMAZOO, MI 49003 MAY 1985 www.americanradiohistory.com r. 4 S w+ nrY 1N to# r' . A. ti W -. A2.0 r`ila °`.' 4 t. zex w 2.44r v 3!r 7é R i A.' _ J r h. .? x'4 744- k fkr. Yj *ADA `rÿ ; . M `fi- dl,_, -'4 k e YA } i T www.americanradiohistory.com INTRODUCTION This is the fourth Winter Supplement to American Radio. Data was gathered from the Winter 1985 Arbitron sweeps (January 3 - March 27,1985). The next edition of American Radio will be issued in early August. It will be the "Spring 85" edition and it will cover approximately 170 markets. ALL ARBITRON AUDIENCE ESTIMATES ARE COPYRIGHTED (1985) BY THE ARBITRON RATINGS COMPANY AND MAY NOT BE QUOTED OR REPRODUCED WITHOUT THEIR PERMISSION. Copyright © 1985 by James Duncan, Jr. This book may not be reproduced in whole or part by mimeograph or any other means without permission. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Address correspondence to : JAMES H. DUNCAN, JR. DUNCAN'S AMERICAN RADIO, INC. BOX 2966 KALAMAZOO, MI 49003 (616) 342 -1356 INDEX ARBITRON INDIVIDUAL MARKET REPORTS (in alphabetical order) Baltimore Houston Philadelphia San Diego Boston Kansas City Phoenix San Francisco Chicago Los Angeles Pittsburgh San Jose Cleveland Louisville Portland, OR Seattle Dallas -FT. Worth Miami Sacramento Tampa -St. Pete Denver New York St. Louis Washington Detroit www.americanradiohistory.com BALTIMORE Arbitron Rank /Pop (12 +): 16/1,911,300 Stations: 40/25 Est. -

Jewish Community Center of San Francisco 3200 California Street San Francisco San Francisco County California

HABSNo. CA-2724 Jewish Community Center of San Francisco 3200 California Street San Francisco San Francisco County California PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA Historic American Buildings Survey National Park Service Western Region Department of the Interior San Francisco, California 94107 HABs C.AL :;<o-sA HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDING SURVEY JEWISH COMMUNITY CENTER OF SAN FRANCISCO HABS No. CA - 2724 Location: 3200 California Street (at Presidio Avenue) . San Francisco, San Francisco County, California 94118 - 1904 UTM Coordinates: 10-548750-4181850 Present Owner: Jewish Community Center of San Francisco Present Occupant: Jewish Community Center of San Francisco Present Use: Vacant Significance The Jewish Community Center of San Francisco QCC SF) was formally incorporated in 1930. However, its roots go back to 1874 with the establishment of the city's first Young Men's Hebrew Association (YMHA). The JCC SF reflects a progressive period in American history that resulted in provision of services and facilities for the underprivileged, and/or for minority ethnic groups. The Jewish Community Center project reflected both national and local efforts to facilitate coordination and effective work among Jewish social, athletic, cultural and charitable organizations by gathering them under one roof. Nationwide the Jewish community was influential in group social work, helping to develop the profession of social workers, and a wide variety of inclusive charitable organizations. In the era spanning 1900 to 1940, Jewish leaders in many American cities promoted the local development of these community centers to serve their communities as a central location for public service organizations, and recreational and social venues. The JCC SF is not closely associated with any specific event in the history of San Francisco or community, nor with any one individual significant to the city, state or nation. -

Harriet Rochlin Collection of Western Jewish History, Date (Inclusive): Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt9p3022wh No online items Finding Aid for the Harriet Rochlin Collection of Western Jewish History Processed by Manuscripts Division staff © 2004 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Harriet 1689 1 Rochlin Collection of Western Jewish History Finding Aid for the Harriet Rochlin Collection of Western Jewish History UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Los Angeles, CA Processed by: Manuscripts Division staff Encoded by: ByteManagers using OAC finding aid conversion service specifications Encoding supervision and revision by: Caroline Cubé Edited by: Josh Fiala, May 2004 © 2004 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Harriet Rochlin Collection of Western Jewish History, Date (inclusive): ca. 1800-1991 Collection number: 1689 Extent: 82 boxes (41.0 linear ft.) 1 oversize box Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Department of Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Abstract: Harriet Shapiro (1924- ) was a freelance writer and contributor of articles, feature stories, and reviews to magazines and scholarly journals. The collection consists of biographical information relating to Jewish individuals, families, businesses, and groups in the western U.S. Includes newspaper and magazine articles, book excerpts, correspondence, advertisements, interviews, memoirs, obituaries, professional listings, affidavits, oral histories, notes, maps, brochures, photographs, and audiocassettes. Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Language: English. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Advance notice required for access. -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

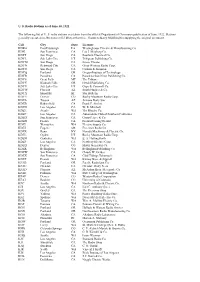

U. S. Radio Stations As of June 30, 1922 the Following List of U. S. Radio

U. S. Radio Stations as of June 30, 1922 The following list of U. S. radio stations was taken from the official Department of Commerce publication of June, 1922. Stations generally operated on 360 meters (833 kHz) at this time. Thanks to Barry Mishkind for supplying the original document. Call City State Licensee KDKA East Pittsburgh PA Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Co. KDN San Francisco CA Leo J. Meyberg Co. KDPT San Diego CA Southern Electrical Co. KDYL Salt Lake City UT Telegram Publishing Co. KDYM San Diego CA Savoy Theater KDYN Redwood City CA Great Western Radio Corp. KDYO San Diego CA Carlson & Simpson KDYQ Portland OR Oregon Institute of Technology KDYR Pasadena CA Pasadena Star-News Publishing Co. KDYS Great Falls MT The Tribune KDYU Klamath Falls OR Herald Publishing Co. KDYV Salt Lake City UT Cope & Cornwell Co. KDYW Phoenix AZ Smith Hughes & Co. KDYX Honolulu HI Star Bulletin KDYY Denver CO Rocky Mountain Radio Corp. KDZA Tucson AZ Arizona Daily Star KDZB Bakersfield CA Frank E. Siefert KDZD Los Angeles CA W. R. Mitchell KDZE Seattle WA The Rhodes Co. KDZF Los Angeles CA Automobile Club of Southern California KDZG San Francisco CA Cyrus Peirce & Co. KDZH Fresno CA Fresno Evening Herald KDZI Wenatchee WA Electric Supply Co. KDZJ Eugene OR Excelsior Radio Co. KDZK Reno NV Nevada Machinery & Electric Co. KDZL Ogden UT Rocky Mountain Radio Corp. KDZM Centralia WA E. A. Hollingworth KDZP Los Angeles CA Newbery Electric Corp. KDZQ Denver CO Motor Generator Co. KDZR Bellingham WA Bellingham Publishing Co. KDZW San Francisco CA Claude W. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles the New Jewish Pioneer

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The New Jewish Pioneer: Capital, Land, and Continuity on the US-Mexico Border A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Chicana/o and Central American Studies by Maxwell Ezra Greenberg 2021 © Copyright by Maxwell Ezra Greenberg 2021 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The New Jewish Pioneer: Capital, Land, and Continuity on the US-Mexico Border by Maxwell Ezra Greenberg Doctor of Philosophy in Chicana/o and Central American Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2021 Professor Robert Chao Romero, Chair Ethnic Studies epistemologies have been central to the historicization and theorization of the US-Mexico border as an ordering regime that carries out structures of settler colonialism, racial capitalism, and white supremacy. While scholars of Jewish history have explored the connections between colonial borders, transnational economic structures, and Jewish merchants, little is known about the role of Jewish entrepreneurs in the process of modern US-Mexico border formation. This dissertation explores how state, corporate, and military imperatives of US imperialism between the American Southwest and Northern Mexico created the conditions for Jewish inclusion into a white settler class and a model of Jewish continuity beyond Europe since the mid-nineteenth century. To explore the imprint of US settler colonialism on Jewish settlement, inclusion, and continuity, Chapter one reviews how Jews have been historicized as exceptional subjects in the contexts of colonial Mexico and the modern American West. Subsequently, Chapter two utilizes archival sources to reinscribe the Jewish border entrepreneur into the history of capitalist and ii military expansion across the new US imperial frontier. -

A History of Toivola, Michigan by Cynthia Beaudette AALC

A A Karelian Christmas (play) A Place of Hope: A History of Toivola, Michigan By Cynthia Beaudette AALC- Stony Lake Camp, Minnesota AALC- Summer Camps Aalto, Alvar Aapinen, Suomi: College Reference Accordions in the Cutover (field recording album) Adventure Mining Company, Greenland, MI Aged, The Over 80s Aging Ahla, Mervi Aho genealogy Aho, Eric (artist) Aho, Ilma Ruth Aho, Kalevi, composers Aho, William R. Ahola, genealogy Ahola, Sylvester Ahonen Carriage Works (Sue Ahonen), Makinen, Minn. Ahonen Lumber Co., Ironwood, Michigan Ahonen, Derek (playwrite) Ahonen, Tauno Ahtila, Eija- Liisa (filmmaker) Ahtisaan, Martti (politician) Ahtisarri (President of Finland 1994) Ahvenainen, Veikko (Accordionist) AlA- Hiiro, Juho Wallfried (pilot) Ala genealogy Alabama Finns Aland Island, Finland Alanen, Arnold Alanko genealogy Alaska Alatalo genealogy Alava, Eric J. Alcoholism Alku Finnish Home Building Association, New York, N.Y. Allan Line Alston, Michigan Alston-Brighton, Massachusetts Altonen and Bucci Letters Altonen, Chuck Amasa, Michigan American Association for State and Local History, Nashville, TN American Finn Visit American Finnish Tourist Club, Inc. American Flag made by a Finn American Legion, Alfredo Erickson Post No. 186 American Lutheran Publicity Bureau American Pine, Muonio, Finland American Quaker Workers American-Scandinavian Foundation Amerikan Pojat (Finnish Immigrant Brass Band) Amerikan Suomalainen- Muistelee Merikoskea Amerikan Suometar Amerikan Uutiset Amish Ammala genealogy Anderson , John R. genealogy Anderson genealogy -

California NEWS SERVICE (June–December) 2007 Annual Report

cans california NEWS SERVICE (June–December) 2007 annual report “Appreciate it’s California- STORY BREAKOUT NUMBER OF RADIO/SPANISH STORIES STATION AIRINGS* specific news…Easy Budget Policy & Priorities 2/1 131 to use…Stories are Children’s Issues 4/3 235 timely…It’s all good…Send Citizenship/Representative Democracy 2 more environment and 130 Civil Rights 3/1 education…Covers stories 160 Community Issues below the threshold of 1 18 the larger news services… Education 4/2 253 Thanks.” Endangered Species/Wildlife 1/1 0 Energy Policy 1 52 California Broadcasters Environment 4/1 230 Global Warming/Air Quality 10/2 574 Health Issues 13/7 “PNS has helped us to 1,565 Housing/Homelessness 7/3 educate Californians on 353 Human Rights/Racial Justice the needs of children 4 264 and families in ways we Immigrant Issues 3/1 128 could have never done on International Relief 5 234 our own by providing an Oceans 2 129 innovative public service Public Lands/Wilderness 6/1 306 that enables us to reach Rural/Farming 2 128 broad audiences and Senior Issues 1/1 54 enhance our impact.” Sustainable Agriculture 1 88 Evan Holland Totals 76/24 5,032 Communications Associate Children’s Defense Fund * Represents the minimum number of times stories were aired. California Launched in June, 2007, the California News Service produced 76 radio and online news stories in the fi rst seven months which aired more than 5,032 times on 215 radio stations in California and 1,091 nationwide. Additionally, 24 Spanish stories were produced. Public News Service California News Service 888-891-9416 800-317-6701 fax 208-247-1830 fax 916-290-0745 * Represents the [email protected] number of times stories were aired. -

The Dictionary Legend

THE DICTIONARY The following list is a compilation of words and phrases that have been taken from a variety of sources that are utilized in the research and following of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups. The information that is contained here is the most accurate and current that is presently available. If you are a recipient of this book, you are asked to review it and comment on its usefulness. If you have something that you feel should be included, please submit it so it may be added to future updates. Please note: the information here is to be used as an aid in the interpretation of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups communication. Words and meanings change constantly. Compiled by the Woodman State Jail, Security Threat Group Office, and from information obtained from, but not limited to, the following: a) Texas Attorney General conference, October 1999 and 2003 b) Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Security Threat Group Officers c) California Department of Corrections d) Sacramento Intelligence Unit LEGEND: BOLD TYPE: Term or Phrase being used (Parenthesis): Used to show the possible origin of the term Meaning: Possible interpretation of the term PLEASE USE EXTREME CARE AND CAUTION IN THE DISPLAY AND USE OF THIS BOOK. DO NOT LEAVE IT WHERE IT CAN BE LOCATED, ACCESSED OR UTILIZED BY ANY UNAUTHORIZED PERSON. Revised: 25 August 2004 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS A: Pages 3-9 O: Pages 100-104 B: Pages 10-22 P: Pages 104-114 C: Pages 22-40 Q: Pages 114-115 D: Pages 40-46 R: Pages 115-122 E: Pages 46-51 S: Pages 122-136 F: Pages 51-58 T: Pages 136-146 G: Pages 58-64 U: Pages 146-148 H: Pages 64-70 V: Pages 148-150 I: Pages 70-73 W: Pages 150-155 J: Pages 73-76 X: Page 155 K: Pages 76-80 Y: Pages 155-156 L: Pages 80-87 Z: Page 157 M: Pages 87-96 #s: Pages 157-168 N: Pages 96-100 COMMENTS: When this “Dictionary” was first started, it was done primarily as an aid for the Security Threat Group Officers in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ). -

George Saunders' CV

George Saunders 214 Scott Avenue Syracuse, New York 13224 (315) 449-0290 [email protected] Education 1988 M.A., English, Emphasis in Creative Writing (Fiction), Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York. Workshop Instructors: Douglas Unger, Tobias Wolff 1981 B.S. Geophysical Engineering, Colorado School of Mines, Golden, Colorado Publications Books: The Braindead Megaphone (Essays), Riverhead Books, September, 2007. This book contains travel pieces on Dubai, Nepal, and the Mexican border, as well as a number of humorous essays and pieces on Twain and Esther Forbes. In Persuasion Nation (stories). Riverhead Books, April 2006. (Also appeared in U.K. as “The Brief and Frightening Reign of Phil,” bundled with the novella of that name.) Paperback released by Riverhead in Spring, 2007. A Bee Stung Me So I Killed All the Fish Riverhead Books, April 2006. This chapbook of non-fiction essays and humor pieces was published in a limited edition alongside the In Persuasion Nation collection. The Brief and Frightening Reign of Phil (Novella-Length Fable). Riverhead Books, September 2005. (In U.K., was packaged with In Persuasion Nation.) Pastoralia (Stories). Riverhead Books, May 2000. International rights sold in UK, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Portugal, the Netherlands, Russia, and other countries. Selected stories also published in Sweden. Paperback redesign released by Riverhead, April 2006. The Very Persistent Gappers of Frip A children’s book, illustrated by Lane Smith. Random House/Villard, August 2000. International rights sold in U.K., Germany, the Netherlands, Italy, Taiwan, Japan, France, China, and other countries. Re-released in hardcover, April 2006, by McSweeney’s Books. CivilWarLand in Bad Decline Six stories and a novella. -

Exhibit 2181

Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 4 Electronically Filed Docket: 19-CRB-0005-WR (2021-2025) Filing Date: 08/24/2020 10:54:36 AM EDT NAB Trial Ex. 2181.1 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 2 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.2 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 3 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.3 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 4 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.4 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 132 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 1 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.5 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 133 Filed 04/15/20 Page 1 of 4 ATARA MILLER Partner 55 Hudson Yards | New York, NY 10001-2163 T: 212.530.5421 [email protected] | milbank.com April 15, 2020 VIA ECF Honorable Louis L. Stanton Daniel Patrick Moynihan United States Courthouse 500 Pearl St. New York, NY 10007-1312 Re: Radio Music License Comm., Inc. v. Broad. Music, Inc., 18 Civ. 4420 (LLS) Dear Judge Stanton: We write on behalf of Respondent Broadcast Music, Inc. (“BMI”) to update the Court on the status of BMI’s efforts to implement its agreement with the Radio Music License Committee, Inc. (“RMLC”) and to request that the Court unseal the Exhibits attached to the Order (see Dkt. -

Of Program Offerings (Range and Frequency of Classroom Usage.Grade-Level Designation) Are Presented in Tabular Format

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 026 858 EM 007 033 By Stegeman, William J.; And Others An Evaluation of San Diego Area Instructional Television AuthorityEducational Program Activities; October 2, 1967 to May 17, 1968 San Diego Area Instructional Television Authority, Calif. Spons Agency-Office of Education (DHEW), Washington, D.C. Pub Date Jul 68 Grant OEG -4 -6-001249-0924 Note-185p. EDRS Price MF-$0.75 HC-$9.35 Descriptors-Consumer Economics, Data Analysis, Equipment Utilization, *Evaluation,Evaluation Methods, *Instructional Television, Interviews, Questionnaires, *School Districts, Surveys Identifiers-Elementary and Secondary Education Act Title III, ESEA Title III, *SanDiego Area /nstructional Television Authority. SDA ITVA An example of evaluation under the requirements of anESEA .Title III °Pace' project,thisreport encompasses the instructionaltelevision development and broadcast activities of the San Diego Area InstructionalTelevision Authority (ITVA). Qualitative data based on a series of teacher interview-questionnaire surveys in ten ITVA county school districts, and quantitative data based on a "Nielson° type survey of program offerings (range and frequency of classroom usage.grade-level designation) are presented in tabular format. Independent surveysfrom the school districts and a report on consumer innovations illustrate the reciprocitybetween producers and users of instructional television. The report outlinesthe budgetary. staff, production, and equipment problems of the project and providesinformation on ITVA organization, planning, hardware, and software in the appendices.(TI) oVAKTAZWZ:Als-MICxzw....4.4.14...=43.046.01..01004t..."41,41a4,., la^ 71 I JIM U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY ASRECEIVED FROM THE C\J PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT.POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICtOF EDUCATION CD POSITION OR POLICY.