Katie Parnell's Final Master's Portfolio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Crown | French Dialogue Transcript | S4:E1

Français Créé par Peter Morgan EPISODE 4.01 “Gold Stick” Alors qu'Elizabeth accueille la première femme Premier ministre britannique et que Charles rencontre une jeune Diana Spencer, une attaque de l'IRA sème la tragédie dans la famille royale. Écrit par: Peter Morgan Réalisé par: Benjamin Caron Date de la première: 15.11.2020 NOTE: This is a transcription of the spoken dialogue and audio, with time-code reference, provided without cost by 8FLiX.com for your entertainment, convenience, and study. This version may not be exactly as written in the original script; however, the intellectual property is still reserved by the original source and may be subject to copyright. Membres de la distribution Olivia Colman ... Queen Elizabeth II Tobias Menzies ... Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh Helena Bonham Carter ... Princess Margaret Gillian Anderson ... Margaret Thatcher Josh O'Connor ... Prince Charles Charles Dance ... Lord Mountbatten Emma Corrin ... Lady Diana Spencer Marion Bailey ... Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother Erin Doherty ... Princess Anne Stephen Boxer ... Denis Thatcher Angus Imrie ... Prince Edward Tom Byrne ... Prince Andrew Freddie Fox ... Mark Thatcher Rebecca Humphries ... Carol Thatcher Charles Edwards ... Martin Charteris P a g e | 1 1 00:00:06,040 --> 00:00:09,960 UNE SÉRIE ORIGINALE NETFLIX 2 00:01:03,280 --> 00:01:05,640 Que font encore les Anglais parmi nous ? 3 00:01:06,640 --> 00:01:11,080 Pourquoi, devant notre rébellion, leur présence en Irlande perdure-t-elle ? 4 00:01:11,160 --> 00:01:12,240 REINE DE LA MORT 5 00:01:12,320 --> 00:01:14,480 Tant de sacrifices ont été faits. -

December 2020

HAPPY BIRTHDAY Marlene Schenter 12/2 Eleanor Briggs 12/7 December 2020 Gloria Brayson 12/8 Estella Massingill 12/9 Ellana Blau 12/11 Fitness! Willa Reynolds 12/13 Frederick Greb 12/17 Join Us! General Manager Joanie Ceballos Roz Schechter 12/18 Marketing Director Jason Goodwill Operations Manager Doris Kelleher Beth Carter 12/19 Kitchen Manager Charley Boonkaw Life Enrichment Director Michele Willemse Duane Schroeder 12/19 Maintenance Supervisor Vicente Macedo Mae Reeves 12/28 Norma Rowe 12/29 www.courtyardvillage.com We had a lot of fun being silly 5500 - 297 - 503 during Halloween week 97225 OR Portland, Avenue 78 SW 4875 th Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 9:00 Trader Joes 10:00 Physical Distancing 9:00 Fred Meyers 10:00 Knitting & 1 Hour 2 10:00 Physical Distancing 3 4 5 9:30 Beaverton Fred Meyers Hour 9:30 Fred Meyers Crocheting Group 10:00 Physical Distancing Hour 1:30 Zoom- “Sip & Study” 1:00 One Day University 10:00 Physical Distancing Hour 1:00 Writer’s Group with Rabbi Posen 1:00 Albertson or Rite Aid 2:15 One Day University 1:30 Mystery Drive 2:00 Movie: Fisherman’s 1:30 Dollar Tree 1:30 Dice Games 3:30 One Day University 1:00 One Day University Friends 3:00 Tablet Games with Karla 7:00 Movie: Fisherman’s 3:30 Decorate for Hanukkah 5:15 Virtual Variety Show 2:15 One Day University 7:00 Movie: National Friends 7:00 Classic Movie: 3:30 One Day University Parks Adventures 7:00 Andy Williams Holiday 3:00 Zoom Social Christmas Show 7:00 Self Made: A Credit to.. -

State Aid $458,176

i.0810 VW t!010NIl'!"'IM !, AV X3S3"10"I I WILMINGTON MEMORIAL LIBRARY 9cO ?B/t(VtO <5, T^i6 /.* WILMINGTON, MASS. '»> i Crter (Trhikahuru - Vilitiinaton COCYMCW I Ml WKMNGION MtWS CD. NC 26TH YEAR, NO 28 WILMINGTON, MASS., JULY 15. 1981 All KOHTS «SBVH) PUB. NO. 635 340 6582346 28 PAGES State aid Selectmen vote arcade rules byDebbiMichals It was a three ring circus with kids piggy banks ... If it makes Game World featured in the you people feel better to have a $458,176 center ring at the Wilmington police officer on Friday and In the middle of the Selectmen's override his veto. Board of Selectmen's meeting on Saturday nights, we'll go along meeting on July 13, Town Stapezynski said that according Monday, July 13. with it." Manager Buzz Stapezynski to Miceli, state aid to Wilmington A group of angry North Another one of the main con- received a call from Represen- under this budget will be $458,176; Wilmington residents calling cerns as cited by Richard tative Miceli, who said that the $64,796 of which came in under the themselves the Concerned Dickinson was that the problem House and Senate had finally school formula and $393,380 came Citizens of North Wilmington that already exists in the parking reached an agreement on the in under the lottery formula. This presented the Board of Selectmen lot across from Elia's market State Budget Stapezynski added $458,176 is out of a total of ap- with a list of grievances con- would worsen with the influx of that Miceli said that even if proximately $235 million in state cerning the new arcade. -

Folk-Tales of Bengal

;v\ i </, E * »^»i BOOK 39- , , , %{> 1^^ FOLK -TALES OF BENGAL MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited LONDON • BOMBAY • CALCUTTA MELBOURNE THE MACMILLAN COMPANY NEW YORK • BOSTON • CHICAGO DALLAS • SAN FRANCISCO THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd. TORONTO "She rushed out of the palace . and came to the upper world." FOLK-TALES OF BENGAL BY THE REV. LAL BEHARI DAY AUTHOR OF 'BENGAL PEASANT LIFE,' ETC. WITH 32 ILLUSTRATIONS IN COLOUR BY WARWICK GOBLE MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED ST. MARTIN'S STREET, LONDON 1912 ^T?^ COPYRIGHT First Edition 1883 With Colovred [llustrations hy Warwick Goble, 191 e TO RICHARD CARNAC TEMPLE CAPTAIN, BENGAL STAFF CORPS F.R.G.S., M.R.A.S., M.A.I., ETC. WHO FIRST SUGGESTED TO THE WRITER THE IDEA OF COLLECTING THESE TALES AND WHO IS DOING SO MUCH IN THE CAUSE OF INDIAN FOLK-LORE THIS LITTLE BOOK IS INSCRIBED PREFACE In my Peasant Life in Bengal I make the peasant boy Govinda spend some hours every evening in listening to stories told by an old w^oman, who was called Sambhu's mother, and who was the best story-teller in the village. On reading that passage, Captain R. C. Temple, of the Bengal Staff Corps, son of the distinguished Indian adminis- trator Sir Richard Temple, wrote to me to say how interesting it would be to get a collection of those unwritten stories which old women in India recite to little children in the evenings, and to ask whether I could not make such a collection. As I was no stranger to the Mahrchen of the Brothers Grimm, to the Norse Tales so admirably told by Dasent, to Arnason's Icelandic Stories translated -

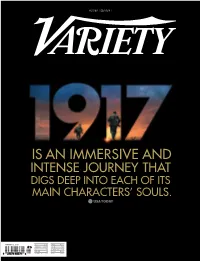

Is an Immersive and Intense Journey That Digs Deep Into Each of Its Main Characters’ Souls

ADVERTISEMENT IS AN IMMERSIVE AND INTENSE JOURNEY THAT DIGS DEEP INTO EACH OF ITS MAIN CHARACTERS’ SOULS. JANUARY 2, 2020 US $9.99 JAPAN ¥1280 CANADA $11.99 CHINA ¥80 UK £ 8 HONG KONG $95 EUROPE €9 RUSSIA 400 AUSTRALIA $14 INDIA 800 3 GOLDEN GLOBE® NOMINATIONS INCLUDING DRAMA BEST DIRECTOR BEST PICTURE SAM MENDES CRITICS’ CHOICE AWARDS NOMINATIONS INCLUDING 8 BEST DIRECTOR BEST PICTURE SAM MENDES THE BEST OF THE LIKE NO FILM YOU A MASTERWORK OF PICTURE YEAR IS HAVE SEEN. THE FIRST ORDER. YOU COULDN’T LOOK AWAY IF YOU WANTED TO. GOLDEN GLOBES YEARS HER MOMENT FOLLOWING ACCLAIMED ROLES IN ‘BOMBSHELL’ AND ‘ONCE UPON A TIME IN HOLLYWOOD,’ ACTOR-PRODUCER MARGOT ROBBIE STORMS THE NEW YEAR WITH A FLURRY OF CREATIVE ENDEAVORS BY KATE AURTHUR P.5 0 P.50 Hollywood on Her Terms Margot Robbie is charging ahead as both an actor and a producer, carving a path for other women along the way. By KATE AURTHUR P.58 Creative Champion AMC Networks programming chief Sarah Barnett competes with streamers by nurturing creators of new cultural hits. By DANIEL HOLLOWAY P.62 Variety Digital Innovators 2020 Twelve leading minds in tech and entertainment are honored for pushing content boundaries. By TODD SPANGLER and JANKO ROETTGERS HANEL; HAIR: BRYCE SCARLETT/THE WALL GROUP/MOROCCAN OIL; MANICURE: TOM BACHIK; DRESS: CHANEL BACHIK; OIL; MANICURE: TOM GROUP/MOROCCAN WALL SCARLETT/THE HANEL; HAIR: BRYCE VARIETY.COM JANUARY 2, 2020 JANUARY (COVER AND THIS PAGE) PHOTOGRAPHS BY ART STREIBER; WARDROBE: KATE YOUNG/THE WALL GROUP; MAKEUP: PATI DUBROFF/FORWARD ARTISTS/C -

Cas Awards April 17, 2021

PRESENTS THE 57TH ANNUAL CAS AWARDS APRIL 17, 2021 SCHEDULE OF EVENTS PRE-SHOW MESSAGES PRESENTATION OF THE CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARD FOR Outstanding Achievement in Sound Mixing for Non-Theatrical Motion Pictures or Limited Series PRESENTATION OF THE CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARD FOR Outstanding Achievement in Sound Mixing for Motion Pictures – Documentary PRESIDENT’S REMARKS Karol Urban CAS MPSE Year in Review, In Memoriam INSTALLATION OF NEW BOARD OF DIRECTORS PRESENTATION OF THE CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARD FOR Outstanding Achievement in Sound Mixing for Television Series – Half-Hour PRESENTATION OF THE CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY Student Recognition Award PRESENTATION OF THE CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARD FOR Outstanding Product for Production PRESENTATION OF THE CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARD FOR Outstanding Product for Post-Production CAS RED CARPET PRESENTATION OF THE CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARD FOR Outstanding Achievement in Sound Mixing for Television Non-Fiction, Variety, Music, Series or Specials PRESENTATION OF CAS FILMMAKER AWARD TO GEORGE CLOONEY PRESENTATION OF THE CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARD FOR Outstanding Achievement in Sound Mixing for Motion Pictures – Animated CAS RED CARPET PRESENTATION OF THE CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARD FOR Outstanding Achievement in Sound Mixing for Television Series – One Hour PRESENTATION OF CAS CAREER ACHIEVEMENT AWARD TO WILLIAM B. KAPLAN CAS PRESENTATION OF THE CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARD FOR Outstanding Achievement in Sound Mixing for Motion Pictures – Live Action AFTER-AWARDS VIRTUAL NETWORKING RECEPTION THE 57TH ANNUAL CAS AWARDS CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY 1 THANK YOU TO OUR SPONSORS DIAMOND SPONSORS PLATINUM SPONSORS STUDENT RECOGNITION AWARD SPONSORS GOLD SPONSORS GROUP SILVER SPONSORS THE 57TH ANNUAL CAS AWARDS CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY 3 PRESIDENT’S LETTER Welcome to the 57th CAS Awards! It has been over a year since last we came together to celebrate our sound mixing community and we are so very happy to see you all. -

Pages Ffuglen:Pages Canon 30/6/08 16:34 Page I

Y Meddwl a’r Dychymyg Cymreig FfugLen Y Ddelwedd o Gymru yn y Nofel Gymraeg o Ddechrau’r Chwedegau hyd at 1990 Enid Jones Gwasg Prifysgol Cymru Pages FfugLen:Pages Canon 30/6/08 16:34 Page i FfugLen Pages FfugLen:Pages Canon 30/6/08 16:34 Page ii Y MEDDWL A’R DYCHYMYG CYMREIG Golygydd Cyffredinol John Rowlands Cyfrolau a ymddangosodd yn y gyfres hyd yn hyn: 1. M. Wynn Thomas (gol.), DiFfinio Dwy Lenyddiaeth Cymru (1995) 2. Gerwyn Wiliams, Tir Neb (1996) (Llyfr y Flwyddyn 1997; Enillydd Gwobr Goffa Ellis Griffith) 3. Paul Birt, Cerddi Alltudiaeth (1997) 4. E. G. Millward, Yr Arwrgerdd Gymraeg (1998) 5. Jane Aaron, Pur fel y Dur (1998) (Enillydd Gwobr Goffa Ellis Griffith) 6. Grahame Davies, Sefyll yn y Bwlch (1999) 7. John Rowlands (gol.), Y Sêr yn eu Graddau (2000) 8. Jerry Hunter, Soffestri’r Saeson (2000) (Rhestr Fer Llyfr y Flwyddyn 2001) 9. M. Wynn Thomas (gol.), Gweld Sêr (2001) 10. Angharad Price, Rhwng Gwyn a Du (2002) 11. Jason Walford Davies, Gororau’r Iaith (2003) (Rhestr Fer Llyfr y Flwyddyn 2004) 12. Roger Owen, Ar Wasgar (2003) 13. T. Robin Chapman, Meibion Afradlon a Chymeriadau Eraill (2004) 14. Simon Brooks, O Dan Lygaid y Gestapo (2004) (Rhestr Hir Llyfr y Flwyddyn 2005) 15. Gerwyn Wiliams, Tir Newydd (2005) 16. Ioan Williams, Y Mudiad Drama yng Nghymru 1880–1940 (2006) 17. Owen Thomas (gol.), Llenyddiaeth mewn Theori (2006) 18. Sioned Puw Rowlands, Hwyaid, Cwningod a Sgwarnogod (2006) 19. Tudur Hallam, Canon Ein Llên (2007) Pages FfugLen:Pages Canon 30/6/08 16:34 Page iii Y MEDDWL A’R DYCHYMYG CYMREIG FfugLen Y Ddelwedd o Gymru yn y Nofel Gymraeg o Ddechrau’r Chwedegau hyd at 1990 Enid Jones GWASG PRIFYSGOL CYMRU CAERDYDD 2008 Pages FfugLen:Pages Canon 30/6/08 16:34 Page iv h Enid Jones, 2008 Cedwir pob hawl. -

Ulysses, Episode XII, "Cyclops"

I was just passing the time of day with old Troy of the D. M. P. at the corner of Arbour hill there and be damned but a bloody sweep came along and he near drove his gear into my eye. I turned around to let him have the weight of my tongue when who should I see dodging along Stony Batter only Joe Hynes. — Lo, Joe, says I. How are you blowing? Did you see that bloody chimneysweep near shove my eye out with his brush? — Soot’s luck, says Joe. Who’s the old ballocks you were taking to? — Old Troy, says I, was in the force. I’m on two minds not to give that fellow in charge for obstructing the thoroughfare with his brooms and ladders. — What are you doing round those parts? says Joe. — Devil a much, says I. There is a bloody big foxy thief beyond by the garrison church at the corner of Chicken Lane — old Troy was just giving me a wrinkle about him — lifted any God’s quantity of tea and sugar to pay three bob a week said he had a farm in the county Down off a hop of my thumb by the name of Moses Herzog over there near Heytesbury street. — Circumcised! says Joe. — Ay, says I. A bit off the top. An old plumber named Geraghty. I'm hanging on to his taw now for the past fortnight and I can't get a penny out of him. — That the lay you’re on now? says Joe. -

Tywysog Cymru”

Deutsche Erstellt von Peter Morgan EPISODE 3.06 “Tywysog Cymru” Inmitten des zunehmenden walisischen Nationalismus im Vorfeld seiner Ernennung zum Prince of Wales wird Charles geschickt, um dort ein Semester zu verbringen und die Sprache zu lernen. Geschrieben von: James Graham | Peter Morgan Regie: Christian Schwochow Sendetermin: 17.11.2019 NOTE: This is a transcription of the spoken dialogue and audio, with time-code reference, provided without cost by 8FLiX.com for your entertainment, convenience, and study. This version may not be exactly as written in the original script; however, the intellectual property is still reserved by the original source and may be subject to copyright. Die Darsteller Olivia Colman ... Queen Elizabeth II Tobias Menzies ... Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh Helena Bonham Carter ... Princess Margaret Ben Daniels ... Lord Snowdon Marion Bailey ... Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother Josh O'Connor ... Prince Charles Erin Doherty ... Princess Anne Charles Dance ... Lord Mountbatten Jason Watkins ... Harold Wilson Mark Lewis Jones ... Edward Millward Nia Roberts ... Silvia Millward David Rintoul ... Michael Adeane Patrick Ryecart ... Duke of Norfolk Sinead Matthews ... Marcia Williams Sam Phillips ... Equerry P a g e | 1 1 00:00:06,480 --> 00:00:09,440 EINE NETFLIX ORIGINAL SERIE 2 00:00:09,520 --> 00:00:13,480 Rege Redner reden rege Reden bei Regen. 3 00:00:13,560 --> 00:00:18,200 Klaus kaut Kraut, Kraut kaut Klaus. Klaus kaut Kraut, Kraut kaut Klaus. 4 00:00:18,280 --> 00:00:19,880 -Rege Redner... -Klaus... 5 00:00:19,960 --> 00:00:24,160 -...Reden bei Regen. -Klaus kaut Kraut. -

Emmy Nominations

2021 Emmy® Awards 73rd Emmy Awards Complete Nominations List Outstanding Animated Program Big Mouth • The New Me • Netflix • Netflix Bob's Burgers • Worms Of In-Rear-Ment • FOX • 20th Century Fox Television / Bento Box Animation Genndy Tartakovsky's Primal • Plague Of Madness • Adult Swim • Cartoon Network Studios The Simpsons • The Dad-Feelings Limited • FOX • A Gracie Films Production in association with 20th Television Animation South Park: The Pandemic Special • Comedy Central • Central Productions, LLC Outstanding Short Form Animated Program Love, Death + Robots • Ice • Netflix • Blur Studio for Netflix Maggie Simpson In: The Force Awakens From Its Nap • Disney+ • A Gracie Films Production in association with 20th Television Animation Once Upon A Snowman • Disney+ • Walt Disney Animation Studios Robot Chicken • Endgame • Adult Swim • A Stoopid Buddy Stoodios production with Williams Street and Sony Pictures Television Outstanding Production Design For A Narrative Contemporary Program (One Hour Or More) The Flight Attendant • After Dark • HBO Max • HBO Max in association with Berlanti Productions, Yes, Norman Productions, and Warner Bros. Television Sara K. White, Production Designer Christine Foley, Art Director Jessica Petruccelli, Set Decorator The Handmaid's Tale • Chicago • Hulu • Hulu, MGM, Daniel Wilson Productions, The Littlefield Company, White Oak Pictures Elisabeth Williams, Production Designer Martha Sparrow, Art Director Larry Spittle, Art Director Rob Hepburn, Set Decorator Mare Of Easttown • HBO • HBO in association with wiip Studios, TPhaeg eL o1w Dweller Productions, Juggle Productions, Mayhem Mare Of Easttown • HBO • HBO in association with wiip Studios, The Low Dweller Productions, Juggle Productions, Mayhem and Zobot Projects Keith P. Cunningham, Production Designer James F. Truesdale, Art Director Edward McLoughlin, Set Decorator The Undoing • HBO • HBO in association with Made Up Stories, Blossom Films, David E. -

Camera Operator & Director of Photography

PRINCESTONE ! +44 (0) 208 883 1616 " [email protected] NIC MILNER assoc. B.S.C. / G.B.C.T. Camera Operator & Director of Photography FEATURES & TV DRAMA: Title Director / DOP Production Co THE PERIPHERAL Vincenzo Natali Warner Bros / Amazon Studios Series: 2nd Unit D.o.P Cast: Gary Carr, T’Nia Miller, Chloe Grace Moretz DREAM HORSE Euros Lyn/Erik Wilson Ffilm Cymru Wales Feature: Race camera operator Cast: Toni Collette, Sian Phillips, Judi Dench BLITHE SPIRIT Edward Hall/Ed Wild Fred Films Feature, 2nd unit camera opereator Cast: Isla Fisher, Dan Stevens, Judi Dench JUDY Rupert Goold / BBC Films / Calamity Films / Pathe UK / Feature, B camera Ole Bratt Birkeland Twentieth Century Fox Cast: Renee Zellweger, Rufus Sewell THE CROWN series 1, 2, 3 & 4 Stephen Daldry, Benjamin Caron, Left Bank Pictures / Sony Pictures Series 1 Daily credits Philip Martin, Julian Jarrold, for Netflix Series 2 A cam - eps 5&6 + Dailies eps 1-4, 7&8 Philippa Lowthorpe, Series 3 A cam - eps 5&6 + Dailies eps. 1-4 Christian Schwochow / Frank Lamm Series 4 tbc Cast: Claire Foy, Olivia Coleman, Matt Smith, Adriano Goldman, Stuart Howell, Tobias Menzies Ole Bratt Birkeland LONDON HAS FALLEN Babak Najafi / Millennium Films / LHF Film / Feature, B camera Ed Wild GBAS Entertainment Cast: Gerard Butler, Morgan Freeman JACK THE GIANT KILLER Bryan Singer / Legendary Films 35mm 2nd unit B camera operator Newton Thomas Sigel Cast: Ewan McGregor, Ian McShane HARRY POTTER & David Yates / Heyday Films / Warner Bros. THE DEATHLY HALLOWS p. 1 & 2 Eduardo Serra / Mike Brewster 35mm 2nd unit B camera operator / D.o.P. -

YAN MILES, ACE Editor

YAN MILES, ACE Editor TELEVISION DIRECTORS PRODUCERS/STUDIOS THE CROWN Series Benjamin Caron Andy Harries, Peter Morgan & Stephen Daldry Sony / Netflix STRANGE NEW THINGS Pilot Kevin MacDonald Bill Shephard / Left Bank Pictures / Amazon SHERLOCK Seasons 3 - 4 Nick Hurran Mark Gatiss, Steven Moffat, Sam Lucas Winner, Best Edited 1-Hr Series – ACE Awards & Various Directors Hartswood Films / BBC Worldwide / PBS Winner, Best Single Cam (Mini-Series) – Emmy Awards Winner, Best Editing – BAFTA Awards GAME OF THRONES 1 Episode Jack Bender Greg Spence / HBO CHILDHOOD’S END Mini-Series Nick Hurran John Lenic, Matthew Graham Paul Leonard / Syfy STRIKE BACK Seasons 1 - 5 Bill Eagles, Andy Harries, Nicki Mousley Lead Editor Dan Percival, Michael Casey, Trevor Hopkins & Michael J. Bassett HBO / Cinemax FORTITUDE Season 1 Nick Hurran Simon Donald, Nina Khan Sam Miller Sky Atlantic / Pivot TV ENDEAVOUR 2 Episodes Ed Bazalgette, Beewan Athwal, Russell Lewis / ITV Giuseppe Capotondi MISSING Season 1 Phil Abraham Mirek Sochor, Gregory Poirier Upcountry Productions / ABC PRIMEVAL Seasons 4 & 5 Cilla Ware Tim Haines, Adrian Hodges, & Mark Everest Beewan Athwal / ITV / BBC America THE PRISONER Mini-Series Nick Hurran Trevor Hopkins, Michele Buck Bill Gallagher / AMC ROME Season 1 Various Directors David Byrne, Frank Doelger, Bruno Heller Editor / 1st Assistant Editor HBO GENERATION KILL Season 1 Simon Cellan Jones Andrea Calderwood, David Simon / HBO 1st Assistant Editor / Assembly Editor Susanna White THE LION IN WINTER TV Movie Andrei Konchalovskiy David