Capital Cities in Interurban Competition: Local Autonomy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal City and Centre of International Cooperation

Bonn Federal City and Centre of International Cooperation Table of Contents Foreword by the Mayor of Bonn 2 Content Bonn – a New Profile 4 Bonn – City of the German Constitution 12 The Federal City of Bonn – Germany’s Second Political Centre 14 International Bonn – Working Towards sustainable Development Worldwide 18 Experience Democracy 28 Bonn – Livable City and Cultural Centre 36 1 Foreword to show you that Bonn’s 320,000 inhabitants may make it a comparatively small town, but it is far from being small-town. On the contrary, Bonn is the city of tomor- “Freude.Joy.Joie.Bonn” – row, where the United Nations, as well as science and Bonn’s logo says everything business, explore the issues that will affect humankind in about the city and is based on the future. Friedrich Schiller’s “Ode to Bonn’s logo, “Freude.Joy.Joie.Bonn.”, incidentally also Joy”, made immortal by our stands for the cheerful Rhenish way of life, our joie de vi- most famous son, Ludwig van vre or Lebensfreude as we call it. Come and experience it Beethoven, in the final choral yourself: Sit in our cafés and beer gardens, go jogging or movement of his 9th Symphony. “All men shall be brot- cycling along the Rhine, run through the forests, stroll hers” stands for freedom and peaceful coexistence in the down the shopping streets and alleys. View the UN and world, values that are also associated with Bonn. The city Post Towers, Godesburg Castle and the scenic Siebenge- is the cradle of the most successful democracy on Ger- birge, the gateway to the romantic Rhine. -

Local and Regional Democracy in Switzerland

33 SESSION Report CG33(2017)14final 20 October 2017 Local and regional democracy in Switzerland Monitoring Committee Rapporteurs:1 Marc COOLS, Belgium (L, ILDG) Dorin CHIRTOACA, Republic of Moldova (R, EPP/CCE) Recommendation 407 (2017) .................................................................................................................2 Explanatory memorandum .....................................................................................................................5 Summary This particularly positive report is based on the second monitoring visit to Switzerland since the country ratified the European Charter of Local Self-Government in 2005. It shows that municipal self- government is particularly deeply rooted in Switzerland. All municipalities possess a wide range of powers and responsibilities and substantial rights of self-government. The financial situation of Swiss municipalities appears generally healthy, with a relatively low debt ratio. Direct-democracy procedures are highly developed at all levels of governance. Furthermore, the rapporteurs very much welcome the Swiss parliament’s decision to authorise the ratification of the Additional Protocol to the European Charter of Local Self-Government on the right to participate in the affairs of a local authority. The report draws attention to the need for improved direct involvement of municipalities, especially the large cities, in decision-making procedures and with regard to the question of the sustainability of resources in connection with the needs of municipalities to enable them to discharge their growing responsibilities. Finally, it highlights the importance of determining, through legislation, a framework and arrangements regarding financing for the city of Bern, taking due account of its specific situation. The Congress encourages the authorities to guarantee that the administrative bodies belonging to intermunicipal structures are made up of a minimum percentage of directly elected representatives so as to safeguard their democratic nature. -

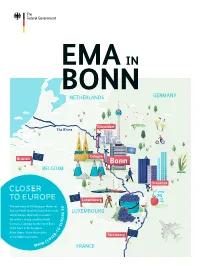

Closer to Europe — Tremendous Opportunities Close By: Germany Is Applying Interview – a Conversation with Bfarm Executive Director Prof

CLOSER TO EUROPE The new home of the European Medicines U E Agency (EMA) should be located centrally . E within Europe. Optimally accessible. P Set within a strong neigh bourhood. O R Germany is applying for the city of Bonn, U E at the heart of the European - O T Rhine Region, to be the location - R E of the EMA’s new home. S LO .C › WWW FOREWORD e — Federal Min öh iste Gr r o nn f H a e rm al e th CLOSER H TO EUROPE The German application is for a very European location: he EU 27 will encounter policy challenges Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. The Institute Bonn. A city in the heart of Europe. Extremely close due to Brexit, in healthcare as in other ar- for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care located in T eas. A new site for the European Medicines nearby Cologne is Europe’s leading institution for ev- to Belgium, the Netherlands, France and Luxembourg. Agency (EMA) must be found. Within the idence-based drug evaluation. The Paul Ehrlich Insti- Situated within the tri-state nexus of North Rhine- EU, the organisation has become the primary centre for tute, which has 800 staff members and is located a mere drug safety – and therefore patient safety. hour and a half away from Bonn, contributes specific, Westphalia, Hesse and Rhineland-Palatinate. This is internationally acclaimed expertise on approvals and where the idea of a European Rhine Region has come to The EMA depends on close cooperation with nation- batch testing of biomedical pharmaceuticals and in re- life. -

Global Metromonitor Geographical Definitions

Note on Global MetroMonitor geographical definitions This note provides further references for the geographic definitions employed for metropolitan areas in the Global MetroMonitor. United States The U.S. Office of Management and Budget defines a metropolitan statistical area based on its containing an urban core of 50,000 or more population. Each metro area may consist of one or more counties including the county of the urban core as well as adjacent counties that have a high degree of social and economic integration (as measured by commuting to work) with the urban core.1 The Global MetroMonitor profiles the 50 largest of these metro areas by GDP, according to estimates from Moody’s Economy.com. Europe For most European metro areas, the definition provided by European Observation Network for Territorial Development and Cohesion (ESPON) was used (2007).2 In brief, this method calculated metro areas by aggregating NUTS3 areas. Exceptions to this rule were made for Dusseldorf (Rhein-Nord portion of the Rhein-Ruhr metropolitan area), Cologne (Rhein-Sud portion of the Rhein-Ruhr metropolitan area), Amsterdam (Randstad Nord portion of the Randstad metropolitan area), Rotterdam (Randstad Zuid portion of the Randstad metropolitan area) and Lille (the French/Belgian trans-border metropolitan area was used). For Oslo, Zurich (Zurich and Winterthur), and Moscow (Federal City of Moscow), NUTS3 data were not available. For these metros, a definition from Cambridge Econometrics, equivalent to the ESPON definition, was used.3 Other Regions For most other metro areas, Oxford Economics defined metro areas based on available definitions from each respective location: Alexandria Contained within the Alexandria Governorate (one of Egypt’s main administrative divisions). -

PUB DATE 90 NOTE 233P. PUB TYPE Guides-Classroom Use-Guides

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 325 426 SO 030 186 TITLE Germany and Georgia: Partners for the Future. Instructional Materials foL Georgia Schools, Volumes I and II. INSTITUTION Georgia State Dept. of Education, Atlanta.; German Federal Foreign Office, Bonn (West Germany). PUB DATE 90 NOTE 233p. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC30 rlus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Ele.lentary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; *Foreign Culture; Instructional Materials; Learning Activities; Social Studies; *State Programs; Teaching Methods IDENTIFIERS *Georgia; *Germany ABSTRACT A collection of lessons is presented for teaching abouL the Federal Republic of Germany that were developed as a result of a study/travel seminar attended by 18 Georgia educators during the summer of 1989. Lessons are designed so that they may either be used individually, J.ntegrated into the curriculum at appropriate places, or be used as a complete unit. Teachers are advised to adjust the materials to accommodate the needs and interests of performance levels of students. Each lesson begins with an outline for teaching that includes instructional objective, and a sequenced list of procedures for using the activities provided with the lesson. Teachers are provided with most of the materials ne.eded for implementation. Volume 1 contains lessons on these topics: introduction to Germany, geography and environment, history and culture, and people. Volume II conta. Ns lesson on these topics concerning contemporary Germany: goveLnment, economics, society, -

Country Compendium

Country Compendium A companion to the English Style Guide July 2021 Translation © European Union, 2011, 2021. The reproduction and reuse of this document is authorised, provided the sources and authors are acknowledged and the original meaning or message of the texts are not distorted. The right holders and authors shall not be liable for any consequences stemming from the reuse. CONTENTS Introduction ...............................................................................1 Austria ......................................................................................3 Geography ................................................................................................................... 3 Judicial bodies ............................................................................................................ 4 Legal instruments ........................................................................................................ 5 Government bodies and administrative divisions ....................................................... 6 Law gazettes, official gazettes and official journals ................................................... 6 Belgium .....................................................................................9 Geography ................................................................................................................... 9 Judicial bodies .......................................................................................................... 10 Legal instruments ..................................................................................................... -

Welcome to Switzerland

messenger IBO 01 Welcome to Organisatoren: Switzerland Greetings from Mathias Wenger, Chairman Albert Einstein: “I have no special talent. I am only passionately curious.” Premium Partners: Thanks to our natural curiosity, we ask questions, learn new things and acquire knowledge. Our pas- sion for biology and our willingness to acquire knowledge bring the participants of the Internation- al Biology-Olympiad (IBO) together. The IBO encourages exchanges between like-minded young- sters from all over the world. On behalf of the IBO 2013 organizers, I would like to welcome you to this exchange in Switzerland. More than a hundred years ago, Albert Einstein submitted his paper “On the electro-dynamics of moving bodies” to the Annalen der Physik journal. He wrote this paper – in Bern’s Old Town where he used to live – driven by his passionate curiosity and the knowledge acquired in his studies. This paper became the base of his special theory of relativity and went down in history. And this – if we First Partners: believe his own words – without any special talent! Curiosity and passion are trademarks of the In- ternational Biology Olympiad. It is also important, even after the end of IBO 2013, to stay corious! Mathias Wenger, MD, Chairman IBO Organizing Committee Messenger This daily newsletter is called mIBO, like the mRNA mole- cule. You’ll find information here about Switzerland, as well as about the IBO 2013. But most importantly, you’ll find pic- tures and texts about the stu- dents’ and jury’s activities of the previous day. Have fun reading it! Volunteers preparing gift bags for you. -

On the Study of Federal Capitals: a Review Article

REVIEW On The Study of Federal Capitals: A Review Article Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance Issue 6: July 2010 http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/ojs/index.php/cjlg Roger Wettenhall Professor Emeritus in Public Administration and Visiting Professor, ANZSOG Institute for Governance, University of Canberra Finance and Governance of Capital Cities in Federal Systems Edited by Enid Slack & Rupak Chattopadhyay (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2009). It is fitting that Canada, as one of the world's leading federations, should play host to important ventures in the study of federal capitals, and in the analysis of how these capitals are governed and financed. A generation ago it was Canadian professor of political science Donald Rowat who produced the first anthology of these capitals. His edited book, with 17 case studies contributed by leading scholars of the time, provided excellent coverage of its subject and has remained the major text in the field for over 30 years. But there have been important developments in the field since Rowat's book was published by University of Toronto Press (Rowat 1973), and we can be thankful that another Canada-based team has produced a sequel volume that brings the story up-to-date and extends it in significant ways (Slack & Chattopadhyay 2009). 158 WETTENHALL: REVIEW: On The Study Of Federal Capitals The new book is a product of the Ottawa-based Forum of Federations, which has a range of relevant conference, publishing, educational and consulting activities. It has previously comprehensively explored the subject of local government and metropolitan regions in federal countries, leading to a range of conferences and publications. -

History of the United States Capitol

HISTORY OF THE UNITED STATES CAPITOL “We have built no national temples but the Capitol; we consult no common oracle but the Constitution.” Representative Rufus Choate, 1833 CHAPTER ONE GRANDEUR ON THE POTOMAC rom a two-hundred-year perspective, Long before the first stone was set, the story it is not easy to grasp the difficulties of the Capitol was intertwined with the effort to F surrounding the location, design, and establish the seat of federal government. The Rev- construction of the United States Capitol. When olution that won the right of self- government for work began in the 1790s, the enterprise had more thirteen independent states started a controversy enemies than friends. Citizens of New York, over the location of the new nation’s capital, a fight Philadelphia, and Baltimore did not want the some historians consider the last battle of the war.1 nation’s capital sited on the Potomac River. The At the close of military hostilities with Great Britain Capitol’s beginnings were stymied by its size, scale, in 1781, the United States was a nation loosely and lack of precedent. In the beginning Congress bound under the Articles of Confederation, a weak did not provide funds to build it. Regional jealousy, form of government with no executive, no judici- political intrigue, and a general lack of architec- ary, and a virtually powerless Congress. Although tural sophistication retarded the work. The the subject of the country’s permanent capital was resources of the remote neighborhood were not discussed during this period, legislators could not particularly favorable, offering little in the way of agree on an issue so taut with regional tension. -

Bonn to Be the New Seat of the European Medicines Agency Contents

Application by the Federal Republic of Germany for the Federal City of Bonn to be the new seat of the European Medicines Agency Contents THE CITY OF BONN AS AN ATTRACTIVE NEW HOME AND HEADQUARTERS 4 1. The assurance that the agency can be set up on site and take up its functions at the date of the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the Union 6 1.1 New building option Bundeskanzlerplatz 7 1.2 New building option Friedrich-Ebert-Allee 8 1.3 Immediate occupancy option Campus Godesberger Allee – an exemplary customised building complex 10 1.4 Immediate occupancy option Am Propsthof in Bonn-Endenich 12 1.5 Further relocation possibilities for organisations and businesses looking to stay close to the EMA 14 1.6 Summary 14 2. The accessibility of the location 16 2.1 Connections 16 2.2 Hotels 20 2.3 Summary 22 3. The existence of adequate education facilities for the children of agency staff 23 3.1 Bilingual kindergartens and day-care centres 23 3.2 Schools 24 3.3 University education in Bonn and the surrounding area 24 3.4 Summary 25 4. Appropriate access to the labour market, social security and medical care for both children and spouses 26 4.1 Access to the region’s attractive and diverse job market 26 4.2 Social security 27 4.3 Medical care 27 4.4 The housing market in Bonn and the region 28 4.5 Summary 29 5. Business continuity 30 5.1 Security and continuity ensured by special expertise offered by BfArM and PEI 30 5.2 Retaining and recruiting highly-qualified human resources 31 5.3 Safeguarding smooth relocation of material and personnel to the new headquarters 31 5.4 High-performance IT environment ensuring operational capability 34 5.5 Summary 37 6. -

Compiled Public Comments | Submitted to Ncpc & Dcop

COMPILED PUBLIC COMMENTS | SUBMITTED TO NCPC & DCOP Includes written testimony and letters received by NCPC and DCOP by the close of the Phase 3 Public Comment Period on October 30, 2013. WRITTEN TESTIMONY Lindsley Williams George R. Clark Benedicte Aubrurn Janet Quigly, Capitol Hill Restoration Society Alma Gates, Neighbors United Trust Sue Hemberger Loretta Newman, Alliance to Preserve the Civil War Defenses of Washington John Belferman Jim Schulman Richard Busch, Historic Districts Coalition Richard Houghton Dorn C. McGrath Jr. Gary Thompson, Advisory Neighborhood Commission 3/4G02 Eugene Abravanel Joseph N. Grano, The Rhodes Tavern-DC Heritage Society Nancy MacWood, Committee of 100 William Haskett Sally L. Berk Laura Phinizy Roger K. Lewis Ben Klemens Kenan T. Fikri Jeff Utz, BF Saul Company and Goulston & Storrs Denis James, Kalorama Citizens Association Robert Robinson and Sherrill Berger, DC Solar United Neighborhoods (DCSUN) Robert T. Richards, Advisory Neighborhood Commission 7B C.L. Kraemer Roberta Faul-Zeitler Judy Chesser David C. Sobelsohn Erik Hein Tersh Boasberg Andrea Rosen ADDITIONAL PUBLIC COMMENTS www.ncpc.gov/heightstudy/comments.php FORMAL LETTERS AND RELATED DOCUMENTS Cheryl Cort, Coalition for Smarter Growth Kindy French David R. Bender, Advisory Neighborhood Commission 2D Donna Hays, Sheridan-Kalorama Historical Association, Inc. William M. Brown, Association of the Oldest Inhabitants of the District of Columbia Marilyn J. Simon, Friendship Neighborhood Association Christopher H. Collins, DC Building Industry Association (DCBIA) Phyllis Myers, State Resource Strategies Penny Pagnao, DC Advisory Neighborhood Commission 3D National Coalition to Save Our Mall Christopher B. Leinberger, George Washington University Rob Nieweg, National Trust for Historic Preservation Reid Nelson, Advisory Council on Historic Preservation The Developers Roundtable James C. -

Facts About Germany Facts About Germany

FACTS ABOUT GERMANY FACTS FACTS ABOUT GERMANY Updated 2018 edition Foreign policy · Society · Research · Economy · Culture Facts about Germany 2 | 3 FACTS ABOUT GERMANY CONTENTS AT A GLANCE EDUCATION & KNOWLEDGE Federal Republic 6 Vibrant Hub of Knowledge 94 Crests & Symbols 8 Dynamic Academic Landscape 98 Demographics 10 Ambitious Cutting-edge Research 102 Geography & Climate 12 Networking Academia 106 Parliament & Parties 14 Research and Academic Relations Policy 108 Political System 16 Excellent Research 110 Federal Government 18 Attractive School System 112 Famous Germans 20 SOCIETY THE STATE & POLITICS Enriching Diversity 114 New Tasks 22 Structuring Immigration 118 Federal State 26 Diverse Living Arrangements 122 Active Politics 30 Committed Civil Society 126 Broad Participation 32 Strong Welfare State 128 Political Berlin 34 Leisure Time and Travel 130 Vibrant Culture of Remembrance 36 Freedom of Religious Worship 132 FOREIGN POLICY CULTURE & THE MEDIA Civil Policy-Shaping Power 38 Vibrant Nation of Culture 134 Committed to Peace and Security 42 Innovative Creative Industry 138 Advocate of European Integration 46 Intercultural Dialogue 140 Protection of Human Rights 50 Cosmopolitan Positions 142 Open Network Partner 54 Rapid Change in the Media 146 Sustainable Development 56 Exciting World Heritage Sites 150 Attractive Language 152 BUSINESS & INNOVATION A Strong Hub 58 WAY OF LIFE Global Player 62 Land of Diversity 154 Lead Markets and Innovative Products 66 Urban Quality of Life 158 Sustainable Economy 70 Sustainable Tourism 160