Microeconomics of Saving

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REP21 December 1974

World Bank Reprint Series: Number Twenty-one REP21 December 1974 Public Disclosure Authorized V.V. Bhatt Some Aspects of Financial Policies and Central Banking in Developing Countries Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Reprinted from World Development 2 (October-December 1974) World Development Vol.2, No.10-12, October-Deceinber 1974, pp. 59-67 59 Some Aspects of Financial Policies and Central Banking in Developing Countries V. V. BHATT Economic Development Institute of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development mechanism and agency as provided by the existence of a Central Bank. What needs special emphasis at an international level is the rationale and urgency of evolving a sound financial structure through the efficient performance of the twin interrelated functions-as promoters and as regulators of the financial system-by Central Banks. 1. SOME ASPECTS OF FINANCIAL POLICIES .. ~~~The main object of this Section is to show the Economic development is not only facilitated but its . pace is quickened by the appropriate development of the significance of saving and flow-of-funds analysis as an financial system--structure of financial institutions, indicator of a set of financial policies-policies relating instruments and interest rates.1 to the structure of financial institutions, instruments and Instrumentsand interest rates.r interest rates-essential for resource mobilization and In any strategy of development, therefore, it is allocation consistent with a country's development essential to emphasize the evolution of a sound and . 6 c well-integrated financial system from the point of view objectives. In a large number of developing countries, the only both of resource mobilization and efficient allocation.2 reliable data available for understanding the trends in the In Section I of this paper, an attempt is made to economy and for policy purposes relate to monetary delineate the broad contours of a set of financial policies flows and the balance of payments. -

Saving in a Financial Institution

SAVING IN A FINANCIAL INSTITUTION i Silverback Consultants Ltd acknowledges the contributions of: Somkwe John-Nwosu Chinyere Agwu Nene Williams Temiloluwa Bamigbola The Consumer Protection Department of The Central Bank of Nigeria. Hajiya Khadijah Kasim Edited by Hajiya Umma Dutse Copyright © 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other non-commercial uses permitted by copyright law. ISBN This material was produced by the Consumer Protection Department of the Central Bank of Nigeria in Collaboration with Silverback Consultants Ltd. 1 01 Introduction 02 Importance of Saving 03 Where to Save Saving at Home (Advantages and Disadvantages) Saving in a Bank and Other Financial Institutions Types of Banks and Other Financial Institutions 04 How to Save What to Consider in Choosing a Bank or Other Financial Institutions Types of Accounts Operating Bank Accounts Electronic Payment Channels 05 Managing Accounts Reconciling Account Complaints Protecting Banking Instruments Protecting Electronic Transactions Rights and Responsibilities of a Bank Customer 06 Conclusion 07 Frequently Used Banking Terms 2 01. Introduction Almost everyone has an idea of what is saving and must have saved in one form or another. This could be towards buying something needed or towards a future project such as building a house, paying school fees, marriage, hospital bills, repay loans or simply for a rainy day. People set aside certain amounts or engage in contributions (esusu, adashe). -

Principles of MICROECONOMICS an Open Text by Douglas Curtis and Ian Irvine

with Open Texts Principles of MICROECONOMICS an Open Text by Douglas Curtis and Ian Irvine VERSION 2017 – REVISION B ADAPTABLE | ACCESSIBLE | AFFORDABLE Creative Commons License (CC BY-NC-SA) advancing learning Champions of Access to Knowledge OPEN TEXT ONLINE ASSESSMENT All digital forms of access to our high- We have been developing superior on- quality open texts are entirely FREE! All line formative assessment for more than content is reviewed for excellence and is 15 years. Our questions are continuously wholly adaptable; custom editions are pro- adapted with the content and reviewed for duced by Lyryx for those adopting Lyryx as- quality and sound pedagogy. To enhance sessment. Access to the original source files learning, students receive immediate per- is also open to anyone! sonalized feedback. Student grade reports and performance statistics are also provided. SUPPORT INSTRUCTOR SUPPLEMENTS Access to our in-house support team is avail- Additional instructor resources are also able 7 days/week to provide prompt resolu- freely accessible. Product dependent, these tion to both student and instructor inquiries. supplements include: full sets of adaptable In addition, we work one-on-one with in- slides and lecture notes, solutions manuals, structors to provide a comprehensive sys- and multiple choice question banks with an tem, customized for their course. This can exam building tool. include adapting the text, managing multi- ple sections, and more! Contact Lyryx Today! [email protected] advancing learning Principles of Microeconomics an Open Text by Douglas Curtis and Ian Irvine Version 2017 — Revision B BE A CHAMPION OF OER! Contribute suggestions for improvements, new content, or errata: A new topic A new example An interesting new question Any other suggestions to improve the material Contact Lyryx at [email protected] with your ideas. -

The Theory of Household Behavior: Some Foundations

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Annals of Economic and Social Measurement, Volume 4, number 1 Volume Author/Editor: Sanford V. Berg, editor Volume Publisher: NBER Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/aesm75-1 Publication Date: 1975 Chapter Title: The Theory of Household Behavior: Some Foundations Chapter Author: Kelvin Lancaster Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c10216 Chapter pages in book: (p. 5 - 21) Annals a! E won;ic and Ss to!fea.t ure,twn t, 4 1975 THE THEORY OF IIOUSEIIOLI) BEHAVIOR: SOME FOUNDATIONS wt' K1LVIN LANCASTER* This paper is concerned with examining the common practice of considering the household to act us if it were a single individuaL Iconcludes rhut aggregate household behavior wifl diverge front the behavior of the typical individual in Iwo important respects, but that the degree of this divergence depend: on well-defined variables--the number of goods and characteristics in the consu;npf ion fecIJflolOgv relative to the size of the household, and thextent of joint consumption within the houseiwid. For appropriate values of these, the degree of divergence may be very small or zero. For some years now, it has been common to refer to the basic decision-making entity with respect to consumption as the "household" by those primarily con- cerned with data collection and analysis and those working mainly with macro- economic models, and as the "individua1' by those working in microeconomic theory and welfare economics. Although one-person households do exist, they are the exception rather than the rule, and the individual and the household cannot be taken to be identical. -

Microeconomics III Oligopoly — Preface to Game Theory

Microeconomics III Oligopoly — prefacetogametheory (Mar 11, 2012) School of Economics The Interdisciplinary Center (IDC), Herzliya Oligopoly is a market in which only a few firms compete with one another, • and entry of new firmsisimpeded. The situation is known as the Cournot model after Antoine Augustin • Cournot, a French economist, philosopher and mathematician (1801-1877). In the basic example, a single good is produced by two firms (the industry • is a “duopoly”). Cournot’s oligopoly model (1838) — A single good is produced by two firms (the industry is a “duopoly”). — The cost for firm =1 2 for producing units of the good is given by (“unit cost” is constant equal to 0). — If the firms’ total output is = 1 + 2 then the market price is = − if and zero otherwise (linear inverse demand function). We ≥ also assume that . The inverse demand function P A P=A-Q A Q To find the Nash equilibria of the Cournot’s game, we can use the proce- dures based on the firms’ best response functions. But first we need the firms payoffs(profits): 1 = 1 11 − =( )1 11 − − =( 1 2)1 11 − − − =( 1 2 1)1 − − − and similarly, 2 =( 1 2 2)2 − − − Firm 1’s profit as a function of its output (given firm 2’s output) Profit 1 q'2 q2 q2 A c q A c q' Output 1 1 2 1 2 2 2 To find firm 1’s best response to any given output 2 of firm 2, we need to study firm 1’s profit as a function of its output 1 for given values of 2. -

ECON - Economics ECON - Economics

ECON - Economics ECON - Economics Global Citizenship Program ECON 3020 Intermediate Microeconomics (3) Knowledge Areas (....) This course covers advanced theory and applications in microeconomics. Topics include utility theory, consumer and ARTS Arts Appreciation firm choice, optimization, goods and services markets, resource GLBL Global Understanding markets, strategic behavior, and market equilibrium. Prerequisite: ECON 2000 and ECON 3000. PNW Physical & Natural World ECON 3030 Intermediate Macroeconomics (3) QL Quantitative Literacy This course covers advanced theory and applications in ROC Roots of Cultures macroeconomics. Topics include growth, determination of income, employment and output, aggregate demand and supply, the SSHB Social Systems & Human business cycle, monetary and fiscal policies, and international Behavior macroeconomic modeling. Prerequisite: ECON 2000 and ECON 3000. Global Citizenship Program ECON 3100 Issues in Economics (3) Skill Areas (....) Analyzes current economic issues in terms of historical CRI Critical Thinking background, present status, and possible solutions. May be repeated for credit if content differs. Prerequisite: ECON 2000. ETH Ethical Reasoning INTC Intercultural Competence ECON 3150 Digital Economy (3) Course Descriptions The digital economy has generated the creation of a large range OCOM Oral Communication of significant dedicated businesses. But, it has also forced WCOM Written Communication traditional businesses to revise their own approach and their own value chains. The pervasiveness can be observable in ** Course fulfills two skill areas commerce, marketing, distribution and sales, but also in supply logistics, energy management, finance and human resources. This class introduces the main actors, the ecosystem in which they operate, the new rules of this game, the impacts on existing ECON 2000 Survey of Economics (3) structures and the required expertise in those areas. -

Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas Sargent, ,, ^ Neil Wallace (P

Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas Sargent, ,, ^ Neil Wallace (p. 1) District Conditions (p.18) Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review vol. 5, no 3 This publication primarily presents economic research aimed at improving policymaking by the Federal Reserve System and other governmental authorities. Produced in the Research Department. Edited by Arthur J. Rolnick, Richard M. Todd, Kathleen S. Rolfe, and Alan Struthers, Jr. Graphic design and charts drawn by Phil Swenson, Graphic Services Department. Address requests for additional copies to the Research Department. Federal Reserve Bank, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55480. Articles may be reprinted if the source is credited and the Research Department is provided with copies of reprints. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis or the Federal Reserve System. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review/Fall 1981 Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas J. Sargent Neil Wallace Advisers Research Department Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis and Professors of Economics University of Minnesota In his presidential address to the American Economic in at least two ways. (For simplicity, we will refer to Association (AEA), Milton Friedman (1968) warned publicly held interest-bearing government debt as govern- not to expect too much from monetary policy. In ment bonds.) One way the public's demand for bonds particular, Friedman argued that monetary policy could constrains the government is by setting an upper limit on not permanently influence the levels of real output, the real stock of government bonds relative to the size of unemployment, or real rates of return on securities. -

1 John Stuart Mill Selections from on the Subjection of Women John

1 John Stuart Mill Selections from On the Subjection of Women John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) was an English philosopher, economist, and essayist. He was raised in strict accord with utilitarian principles by his economist father James Mill, the founder of utilitarian philosophy. John Stuart recorded his early training and subsequent near breakdown in in his Autobiography (“A Crisis in My Mental History. One Stage Onward”), published after his death by his step-daughter, Helen Taylor, in 1873. His strictly intellectual training led to an early crisis which, as he records in this chapter, was only relieved by reading the poetry of William Wordsworth. During his life, Mill published a number of works on economic and political issues, including the Principles of Political Economy (1848), Utilitarianism (1863), and On Liberty (1859). After his death, besides the Autobiography, his step-daughter published Three Essays on Religion in 1874. On the Subjection of Women (1869) is Mill’s utilitarian argument for the complete equality of women with men. Scholars think that it was greatly influenced by Mill’s discussions with Harriet Taylor, whom Mill married in 1851. The essay is addressed to men, the rulers and controllers of nineteenth-century society, and is his contribution to what had become known as “the woman question,” that is, what liberties should be accorded to women in society. As such, it is a clear and still-relevant contribution to the ongoing discussion of women’s rights and their desire to achieve what Mill announces in his opening thesis, “perfect equality.” Information readily available on the internet has not been glossed. -

FALL 2021 COURSE SCHEDULE August 23 –– December 9, 2021

9/15/21 DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS FALL 2021 COURSE SCHEDULE August 23 –– December 9, 2021 Course # Class # Units Course Title Day Time Location Instruction Mode Instructor Limit 1078-001 20457 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 1 MWF 8:00-8:50 ECON 117 IN PERSON Bentz 47 1078-002 20200 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 1 MWF 6:30-7:20 ECON 119 IN PERSON Hurt 47 1078-004 13409 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 1 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Marein 71 1088-001 18745 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 2 MWF 6:30-7:20 HLMS 141 IN PERSON Zhou, S 47 1088-002 20748 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 2 MWF 8:00-8:50 HLMS 211 IN PERSON Flynn 47 2010-100 19679 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Keller 500 2010-200 14353 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Carballo 500 2010-300 14354 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Bottan 500 2010-600 14355 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Klein 200 2010-700 19138 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Gruber 200 2020-100 14356 4 Principles of Macroeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Valkovci 400 3070-010 13420 4 Intermediate Microeconomic Theory MWF 9:10-10:00 ECON 119 IN PERSON Barham 47 3070-020 21070 4 Intermediate Microeconomic Theory TTH 2:20-3:35 ECON 117 IN PERSON Chen 47 3070-030 20758 4 Intermediate Microeconomic Theory TTH 11:10-12:25 ECON 119 IN PERSON Choi 47 3070-040 21443 4 Intermediate Microeconomic Theory MWF 1:50-2:40 ECON 119 IN PERSON Bottan 47 3080-001 22180 3 Intermediate Macroeconomic Theory MWF 11:30-12:20 -

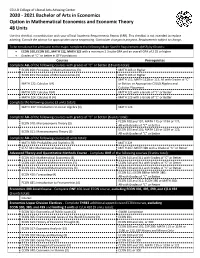

2020-2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical

CSULB College of Liberal Arts Advising Center 2020 - 2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical Economics and Economic Theory 48 Units Use this checklist in combination with your official Academic Requirements Report (ARR). This checklist is not intended to replace advising. Consult the advisor for appropriate course sequencing. Curriculum changes in progress. Requirements subject to change. To be considered for admission to the major, complete the following Major Specific Requirements (MSR) by 60 units: • ECON 100, ECON 101, MATH 122, MATH 123 with a minimum 2.3 suite GPA and an overall GPA of 2.25 or higher • Grades of “C” or better in GE Foundations Courses Prerequisites Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (18 units total): ECON 100: Principles of Macroeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher ECON 101: Principles of Microeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher MATH 111; MATH 112B or 113; All with Grades of “C” MATH 122: Calculus I (4) or Better; or Appropriate CSULB Algebra and Calculus Placement MATH 123: Calculus II (4) MATH 122 with a Grade of “C” or Better MATH 224: Calculus III (4) MATH 123 with a Grade of “C” or Better Complete the following course (3 units total): MATH 247: Introduction to Linear Algebra (3) MATH 123 Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (6 units total): ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 310: Microeconomic Theory (3) All with Grades of “C” or Better ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 311: Macroeconomic Theory (3) All with -

Perceived Financial Preparedness, Saving Habits, and Financial Security CFPB Office of Research

Perceived Financial Preparedness, Saving Habits, and Financial Security CFPB Office of Research SEPTEMBER 2020 The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s (CFPB, the Bureau) Start Small, Save Up initiative aims to promote the importance of building a basic savings cushion and saving habits among U.S. consumers as a pathway to increased financial well-being and financial security.1 Having a savings cushion or a habit of saving can help consumers feel more in control of their finances and allow them to weather financial shocks more easily. Indeed, previous research shows that many consumers experience financial shocks, and that savings can help buffer against shocks and provide financial security.2 Further, previous research has also found a relationship between savings and financial well-being that suggests that having savings can help consumers feel more financially secure.3 This brief uses data from the Bureau’s Making Ends Meet survey to explore consumers’ savings- related behaviors, experiences, and outcomes. We examine subjective experiences primarily as they relate to financial well-being and feelings of control over finances,4 while consumers’ objective financial situations are explored using self-reported responses to questions about difficulty paying bills, saving habits, and money in checking and savings accounts. Focusing on these and other financial factors, such as income, allows us to better understand how consumers 1 This Office of Research research brief (No. 2020-2) was written by Caroline Ratcliffe, Melissa Knoll, Leah Kazar, Maxwell Kennady, and Marie Rush. 2 McKernan, Ratcliffe, Kalish, and Braga (2016); Mills et al. (2016); Mills et al. (2019); Ratcliffe, Burke, Gardner, and Knoll (2020). -

Capitalism and Society

Capitalism and Society Volume 3, Issue 3 2008 Article 2 The Many Contributions of Edmund Phelps: American Economic Association Luncheon Speech Honoring the 2006 Nobel Laureate in Economics James J. Heckman∗ ∗University of Chicago; Geary Institute, University College Dublin; and the American Bar Foundation Copyright c 2008 The Berkeley Electronic Press. All rights reserved. Heckman: The Many Contributions of Edmund Phelps The following speech was given at the American Economic Association Annual Meetings, New Orleans, January 5, 2008. This draft was revised August 14, 2008. This research was supported by the American Bar Foundation and the Geary Institute, University College Dublin. Throughout his career, Ned Phelps has made fundamental contributions to growth theory, macroeconomics, public finance and social welfare theory that deserved the high recognition accorded by the Nobel Prize committee in October, 2006. He is one of the most original thinkers in economics. The citation issued when Phelps was made a Distinguished Fellow of the American Economic Association still speaks for the community of economists today: The collection of papers from a conference that he organized, Microeconomic Foundations, pushed questions about theoretical foundations to the front of the research agenda and changed forever our notion of what constitutes an acceptable macroeconomic theory... Throughout his career Phelps has been willing to step outside of the existing analytical framework and rethink the basic issues... He continues to push theorists and policy makers to rethink their analysis of expectations, inflation, and unemployment and to set a high standard for what it means to be an economic theorist. (American Economic Association 2001) Phelps’s output of original concepts, models and theorems has been vast.