Mchenry Colostate 0053N 164

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. Equity Analyst Report

Merrimack College Merrimack ScholarWorks Honors Senior Capstone Projects Honors Program Spring 2016 Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. Equity Analyst Report Brian Nelson Goncalves Merrimack College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.merrimack.edu/honors_capstones Part of the Finance and Financial Management Commons Recommended Citation Goncalves, Brian Nelson, "Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. Equity Analyst Report" (2016). Honors Senior Capstone Projects. 7. https://scholarworks.merrimack.edu/honors_capstones/7 This Capstone - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at Merrimack ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Merrimack ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Head: TAKE-TWO INTERACTIVE SOFTWARE, INC. EQUITY ANALYST REPORT 1 Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. Equity Analyst Report Brian Nelson Goncalves Merrimack College Honors Department May 5, 2016 Author Notes Brian Nelson Goncalves, Finance Department and Honors Program, at Merrimack Collegei. Brian Nelson Goncalves is a Senior Honors student at Merrimack College. This report was created with the intent to educate investors while also serving as the students Senior Honors Capstone. Full disclosure, Brian is a long time share holder of Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. 1 Running Head: TAKE-TWO INTERACTIVE SOFTWARE, INC. EQUITY ANALYST REPORT 2 Table of Contents -

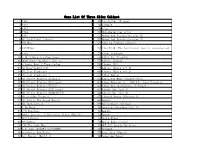

2475 in 1 Game List

Game List Of Three Sides Cabinet 1 1941 47 Air Gallet (Taiwan) 2 1942 48 Airwolf 3 1943 49 Ajax 4 1944 50 Akkanbeder(ver 2.5j) 5 1945 51 Akuma-Jou Dracula(version N) 6 10 Yard Fight (Japan) 52 Akuma-Jou Dracula(version P) 7 1943kai 53 Ales no Tsubasa (Japan) 8 1945Plus 54 Alex Kidd: The Lost Stars (set 2, unprotected) 9 19xx 55 Alien Syndrome 10 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge 56 Alien vs. Predator 11 2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 57 Aliens (Japan) 12 3 Count Bout / Fire Suplex 58 Aliens (US) 13 3D_Beastorizer(US) 59 Aliens (World set 1) 14 3D_Star Gladiator 60 Aliens (World set 2) 15 3D_Star Gladiator 2 61 Alley Master 16 3D_Street Fighter EX(Asia) 62 Alligator Hunt (unprotected) 17 3D_Street Fighter EX(Japan) 63 Alpha Mission II / ASO II - Last Guardian 18 3D_Street Fighter EX(US) 64 Alpha One (prototype, 3 lives) 19 3D_Street Fighter EX2(Japan) 65 Alpine Ski (set 1) 20 3D_Street Fighter EX2PLUS(US) 66 Alpine Ski (set 2) 21 3D_Strider Hiryu 2 67 Altered Beast (Version 1) 22 3D_Tetris The Grand Master 68 Ambush 23 3D_Toshinden 2 69 Ameisenbaer (German) 24 4 En Raya 70 American Speedway (set 1) 25 4-D Warriors 71 Amidar 26 64th. Street - A Detective Story (World) 72 Amigo 27 800 Fathoms 73 Andro Dunos 28 88 Games! 74 Angel Kids (Japan) 29 '99 The Last War 75 APB-All Points Bulletin 30 A.B. Cop (FD1094 317-0169b) 76 Appoooh 31 Acrobatic Dog_Fight 77 Aqua Jack (World) 32 Act-Fancer (World 1) 78 Aquarium(Japan) 33 Act-Fancer (World 2) 79 Arabian Act-Fancer Cybernetick Hyper Weapon (Japan 34 80 Arabian (Atari) revision 1) 35 Action Fighter 81 Arabian -

Newagearcade.Com 5000 in One Arcade Game List!

Newagearcade.com 5,000 In One arcade game list! 1. AAE|Armor Attack 2. AAE|Asteroids Deluxe 3. AAE|Asteroids 4. AAE|Barrier 5. AAE|Boxing Bugs 6. AAE|Black Widow 7. AAE|Battle Zone 8. AAE|Demon 9. AAE|Eliminator 10. AAE|Gravitar 11. AAE|Lunar Lander 12. AAE|Lunar Battle 13. AAE|Meteorites 14. AAE|Major Havoc 15. AAE|Omega Race 16. AAE|Quantum 17. AAE|Red Baron 18. AAE|Ripoff 19. AAE|Solar Quest 20. AAE|Space Duel 21. AAE|Space Wars 22. AAE|Space Fury 23. AAE|Speed Freak 24. AAE|Star Castle 25. AAE|Star Hawk 26. AAE|Star Trek 27. AAE|Star Wars 28. AAE|Sundance 29. AAE|Tac/Scan 30. AAE|Tailgunner 31. AAE|Tempest 32. AAE|Warrior 33. AAE|Vector Breakout 34. AAE|Vortex 35. AAE|War of the Worlds 36. AAE|Zektor 37. Classic Arcades|'88 Games 38. Classic Arcades|1 on 1 Government (Japan) 39. Classic Arcades|10-Yard Fight (World, set 1) 40. Classic Arcades|1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) 41. Classic Arcades|18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) 42. Classic Arcades|1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) 43. Classic Arcades|1942 (Revision B) 44. Classic Arcades|1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) 45. Classic Arcades|1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) 46. Classic Arcades|1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) 47. Classic Arcades|1945k III 48. Classic Arcades|19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) 49. Classic Arcades|2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 50. Classic Arcades|2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 51. -

Boisvert-Storey-Sony Case Brief

Storey C204 Summer 2014 Case Study BE MOVED SITUATION Sony Corporation is a 68-year old multinational based in Tokyo. In 2012, the tech giant employed 173,000 people, with corporate headquarters in Japan, Europe, and America. In May 2014, the company was down to 146,300, cutting 26,700 as part of CEO Kaz Hirai’s “One Sony” plan. Recently, the firm eVen sold former office buildings in Tokyo for $156 million (Inagaki). This followed a similar $1.2 billion sale in 2013. After seVeral years of losses, Sony’s situation appears critical. In the last fiscal year, the company lost $1.25 billion. EVen the gaming diVision, where the Playstation console family (PS2, PS3, PS4) is projected to sell 17 million units this year, lost $78 million (Quarterly Results). There are many causes: Sony’s jettisoning of its PC brand Vaio, the poor performance and planned spinoff of Sony’s teleVision diVision, PS4 launch and marketing costs, the struggling PSVita, R&D costs for Sony’s Project Morpheus, and the fluctuation of exchange rate markets. For the current year, Sony is projecting a $489 million loss. How sustainable is Sony’s current business model? Will the success of the PS4 lead to renewed profitability for the games diVision and the company as a whole? Perhaps opportunities in new markets can spark a turn-around. The company’s core businesses are electronic entertainment (Sony Computer Entertainment, Sony Music Entertainment, and Sony Pictures Entertainment) and hardware (Sony Mobile Communications and Sony Electronics). Though it also dabbles in financial serVices, publishing, and medical imaging, electronics represents roughly two-thirds of the corporation’s reVenue (Sony Annual Report 2011, 2013). -

Classic Gaming Expo 2005 !! ! Wow

San Francisco, California August 20-21, 2005 $5.00 Welcome to Classic Gaming Expo 2005 !! ! Wow .... eight years! It's truly amazing to think that we 've been doing this show, and trying to come up with a fresh introduction for this program, for eight years now. Many things have changed over the years - not the least of which has been ourselves. Eight years ago John was a cable splicer for the New York phone company, which was then called NYNEX, and was happily and peacefully married to his wife Beverly who had no idea what she was in for over the next eight years. Today, John's still married to Beverly though not quite as peacefully with the addition of two sons to his family. He's also in a supervisory position with Verizon - the new New York phone company. At the time of our first show, Sean was seven years into a thirteen-year stint with a convenience store he owned in Chicago. He was married to Melissa and they had two daughters. Eight years later, Sean has sold the convenience store and opened a videogame store - something of a life-long dream (or was that a nightmare?) Sean 's family has doubled in size and now consists of fou r daughters. Joe and Liz have probably had the fewest changes in their lives over the years but that's about to change . Joe has been working for a firm that manages and maintains database software for pharmaceutical companies for the past twenty-some years. While there haven 't been any additions to their family, Joe is about to leave his job and pursue his dream of owning his own business - and what would be more appropriate than a videogame store for someone who's life has been devoted to collecting both the games themselves and information about them for at least as many years? Despite these changes in our lives we once again find ourselves gathering to pay tribute to an industry for which our admiration will never change . -

Download 80 PLUS 4983 Horizontal Game List

4 player + 4983 Horizontal 10-Yard Fight (Japan) advmame 2P 10-Yard Fight (USA, Europe) nintendo 1941 - Counter Attack (Japan) supergrafx 1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) mame172 2P sim 1942 (Japan, USA) nintendo 1942 (set 1) advmame 2P alt 1943 Kai (Japan) pcengine 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) mame172 2P sim 1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) mame172 2P sim 1943 - The Battle of Midway (USA) nintendo 1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) mame172 2P sim 1945k III advmame 2P sim 19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) mame172 2P sim 2010 - The Graphic Action Game (USA, Europe) colecovision 2020 Super Baseball (set 1) fba 2P sim 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) mame078 4P sim 36 Great Holes Starring Fred Couples (JU) (32X) [!] sega32x 3 Count Bout / Fire Suplex (NGM-043)(NGH-043) fba 2P sim 3D Crazy Coaster vectrex 3D Mine Storm vectrex 3D Narrow Escape vectrex 3-D WorldRunner (USA) nintendo 3 Ninjas Kick Back (U) [!] megadrive 3 Ninjas Kick Back (U) supernintendo 4-D Warriors advmame 2P alt 4 Fun in 1 advmame 2P alt 4 Player Bowling Alley advmame 4P alt 600 advmame 2P alt 64th. Street - A Detective Story (World) advmame 2P sim 688 Attack Sub (UE) [!] megadrive 720 Degrees (rev 4) advmame 2P alt 720 Degrees (USA) nintendo 7th Saga supernintendo 800 Fathoms mame172 2P alt '88 Games mame172 4P alt / 2P sim 8 Eyes (USA) nintendo '99: The Last War advmame 2P alt AAAHH!!! Real Monsters (E) [!] supernintendo AAAHH!!! Real Monsters (UE) [!] megadrive Abadox - The Deadly Inner War (USA) nintendo A.B. -

Video Games and Costume Art -Digitalizing Analogue Methods of Costume Design

Video Games and Costume Art -digitalizing analogue methods of costume design Heli Salomaa MA thesis 30 credits Department of Film, Television and Scenography Master’s Degree Programme in Design for Theatre, Film and Television Major in Costume Design Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture Supervisor: Sofia Pantouvaki Advisors: Petri Lankoski, Maarit Kalmakurki 2018 Aalto University, P.O. BOX 11000, 00076 AALTO www.aalto.fi Master of Arts thesis abstract ! Author Heli Salomaa Title of thesis Video Games and Costume Art - digitalizing analogue methods of costume design Department Department of Film, Television and Scenography Year 2018 Number of pages 100 Language English Degree programme Master's Degree Programme in Design for Theatre, Film and Television, Major in Costume Design Abstract This thesis explores ways of integrating a costume professional to the character art team in the game industry. The research suggests, that integrating costume knowledge into the character design pipeline increases the storytelling value of the characters and provides tools for the narrative. The exploration of integrating a costume professional into game character creation as a process is still rare and little information of costume in games and experiences in transferring an analogue character building skillset into a digital one can be found, therefore this research was generated to provide knowledge on the subject. The research's main emphasis is on immersion-driven AAA-games that employ 3D-graphics and human characters and are either photorealistic or represent stylized realism. Technology for depicting reality is advancing and digital industries have become aware of the extensive skills required to depict increasingly realistic worlds. -

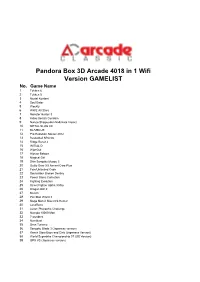

Pandora Box 3D Arcade 4018 in 1 Wifi Version GAMELIST No

Pandora Box 3D Arcade 4018 in 1 Wifi Version GAMELIST No. Game Name 1 Tekken 6 2 Tekken 5 3 Mortal Kombat 4 Soul Eater 5 Weekly 6 WWE All Stars 7 Monster Hunter 3 8 Kidou Senshi Gundam 9 Naruto Shippuuden Naltimate Impact 10 METAL SLUG XX 11 BLAZBLUE 12 Pro Evolution Soccer 2012 13 Basketball NBA 06 14 Ridge Racer 2 15 INITIAL D 16 WipeOut 17 Hitman Reborn 18 Magical Girl 19 Shin Sangoku Musou 5 20 Guilty Gear XX Accent Core Plus 21 Fate/Unlimited Code 22 Soulcalibur Broken Destiny 23 Power Stone Collection 24 Fighting Evolution 25 Street Fighter Alpha 3 Max 26 Dragon Ball Z 27 Bleach 28 Pac Man World 3 29 Mega Man X Maverick Hunter 30 LocoRoco 31 Luxor: Pharaoh's Challenge 32 Numpla 10000-Mon 33 7 wonders 34 Numblast 35 Gran Turismo 36 Sengoku Blade 3 (Japanese version) 37 Ranch Story Boys and Girls (Japanese Version) 38 World Superbike Championship 07 (US Version) 39 GPX VS (Japanese version) 40 Super Bubble Dragon (European Version) 41 Strike 1945 PLUS (US version) 42 Element Monster TD (Chinese Version) 43 Ranch Story Honey Village (Chinese Version) 44 Tianxiang Tieqiao (Chinese version) 45 Energy gemstone (European version) 46 Turtledove (Chinese version) 47 Cartoon hero VS Capcom 2 (American version) 48 Death or Life 2 (American Version) 49 VR Soldier Group 3 (European version) 50 Street Fighter Alpha 3 51 Street Fighter EX 52 Bloody Roar 2 53 Tekken 3 54 Tekken 2 55 Tekken 56 Mortal Kombat 4 57 Mortal Kombat 3 58 Mortal Kombat 2 59 The overlord continent 60 Oda Nobunaga 61 Super kitten 62 The battle of steel benevolence 63 Mech -

Bandai Namco Amusement Europe

BANDAI NAMCO AMUSEMENT EUROPE 2018 AUTUMN Product Catalogue BANDAI NAMCO Amusement Europe Ltd. Prize Sales James Anderson Snezhana Nikolova Darrell Simmonds Sean Franks Commercial & Sales Director Finance Manager EMEA Sales Manager Northern Sales Executive [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +44 (0)20 8324 6265 Tel: +44 (0)20 8324 6278 Mob: +44 (0)78 0260 9957 Mob: +44 (0)75 8563 1436 Mob: +44 (0)78 8060 0033 Fax : +44 (0)20 8324 6024 Creative Department Kazuko Minagawa Stephen Walters Ashly Keane Amreet Grewal Corporate Planning and Sales Ledger Controller Creative & Product Creative Assistant & Communication Manager Development Manager Website Administrator [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +44 (0)20 8324 6277 Tel: +44 (0)20 8324 6214 Tel: +44 (0)20 8324 6267 Tel: +44 (0)20 8324 6216 Mob: +44 (0)79 0069 0518 Mob: +44 (0)75 5443 3458 International Machine Sales Customer Services Kjeld Erichsen Josh Hurst Steve Ansell Peter Monaghan International Business Export Sales Manager Customer Services Director Sales and Service Manager Development Manager [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +44 (0)20 8324 6207 Tel: +44 (0)20 8324 6203 Tel: +44 (0)20 8324 6208 Tel: +44 (0)20 8324 6285 Mob : +44 (0)7881 010 655 Fax: +44 (0)20 8324 6126 Mob: +45 2622 1818 Mob: +44 (0)78 0260 9959 Domestic (UK & Ireland) Machine Sales John -

Game List of Game Elf (Vertical) 001.Ms

Game list of game elf (Vertical) 001.Ms. Pac-Man ▲ 044.Arkanoid 002.Ms. Pac-Man (speedup) 045.Super Qix 003.Ms. Pac-Man Plus 046.Juno First 004.Galaga 047.Xevious 005.Frogger 048.Mr. Do's Castle 006.Frog 049.Moon Cresta 007.Donkey Kong 050.Pinball Action 008.Crazy Kong 051.Scramble 009.Donkey Kong Junior 052.Super Pac-Man 010.Donkey Kong 3 053.Bomb Jack 011.Galaxian 054.Shao-Lin's Road 012.Galaxian Part X 055.King & Balloon 013.Galaxian Turbo ▲ 56.1943 014.Dig Dug 057.Van-Van Car 015.Crush Roller 058.Pac-Man Plus 016.Mr. Do! 059.Pac & Pal 017.Space Invaders Part II 060.Dig Dug II 018.Super Invaders (EMAG) 061.Amidar 019.Return of the Invaders 062.Zaxxon ▲ 020.Super Space Invaders '91 063.Super Zaxxon 021.Pac-Man 064.Pooyan 022.PuckMan ▲ 065.Pleiads 023.PuckMan (speedup) 066.Gun.Smoke 024.New Puck-X 067.The End 025.Newpuc2 ▲ 068.1943 Kai 026.Galaga 3 069.Congo Bongo 027.Gyruss 070.Jumping Jack 028.Tank Battalion 071.Big Kong 29.1942 072.Bongo 030.Lady Bug 073.Gaplus 031.Burger Time 074.Ms. Pac Attack 032.Mappy 075.Abscam 033.Centipede 076.Ajax ▲ 034.Millipede 077.Ali Baba and 40 Thieves 035.Jr. Pac-Man ▲ 078.Finalizer - Super Transformation 036.Pengo 079.Arabian 037.Son of Phoenix 080.Armored Car 038.Time Pilot 081.Astro Blaster 039.Super Cobra 082.Astro Fighter 040.Video Hustler 083.Astro Invader 041.Space Panic 084.Battle Lane! 042.Space Panic (harder) 085.Battle-Road, The ▲ 043.Super Breakout 086.Beastie Feastie Caution: ▲ No flipped screen’s games ! 1 Game list of game elf (Vertical) 087.Bio Attack 130.Go Go Mr. -

Innovation in the Video Game Industry: the Role of Nintendo

Department of Business and Management Course of Managerial Decision Making Innovation in the video game industry: the role of Nintendo Prof. Luigi Marengo Prof. Luca De Benedictis SUPERVISOR CO-SUPERVISOR Fulvio Nicolamaria ID No.705511 CANDIDATE Academic Year 2019/2020 To those who belong to my past, that have made me what I am and to those who belong to my present, who give me the strength to advance 2 Foreword Writing a paper with the gaming industry as one of the main themes may seem, in the eyes of the reader that is not properly involved in the subject, as something atypical and far from the academic conception of what should be debated in a thesis. However, in a work that concerns Economics, even an industry dedicated solely to entertainment like that one of video game can be an interesting challenge. Moreover, each thesis should aim to develop researches on new topics and to process the results. What better way to do this if not by exploring overlooked fields of research? The idea of a work involving Nintendo company as the main topic was among the possible research options, and choosing it as the theme to conclude the Master Degree was the goal I had proposed to myself for a long time. The involvement of the subject of innovation comes from the belief of its importance; since these two themes, innovation and Nintendo, could be easily combined, it was natural to create this work in some way dual. Making available to any reader topics so far from usual ones, without sacrificing the academic character of the paper, was both a challenge and a target. -

Mass-Effect-Manuals

CYAN MAGENTA YELLOW BLACK DIE 179223 EA 179223_A MPS 05.12.08 rw 2 Explore the Universe of Mass Effect Help shape the future of your favorite sci-fi experience by joining BioWare’s Mass Effect Sign up for a free* BioWare account to get into the inner • Discuss your ideas with the Mass Effect developers • Receive special content • Access exclusive forums • Contribute content Gain recognition for your work from Mass Effect • fans around the world Free subscription by joining the Mass Effect BioWare • Community Newsletter for all the latest Mass Effect news, game announcements, and more www.masseffect.com Don’t let technical issues stop you from saving the galaxy For technical support, including installation, performance, and gameplay related issues, go to: http://support.ea.com Notice Electronic Arts reserves the right to make improvements in the product described in this manual at any time and without notice. This manual and the product described in this manual are copyrighted. All rights reserved. Proof of Purchase Mass Effect™ 1908105 ISBN 0-7845-4664-9 0 14633 19081 6 * INTERNET CONNECTION REQUIRED Electronic Arts Inc. 209 Redwood Shores Parkway, Redwood City, CA 94065. _MASSpcMCVmech.ai L.Siegel Helvetica Times MASS_pcMCVartCOLOR.tif Prints 4 color EA_SigLogo_MassEffect_Black_Outline.psd 1908105 M.David Univers Arial Special notes here 4/28/08 3:11 J.Lee Futura Etc. FINAL MPS CS3 K.Toth 7. Disclaimer of Warranties. EXCEPT FOR THE LIMITED WARRANTY ON RECORDING MEDIA FOUND IN THE PRODUCT MANUAL, AND TO THE FULLEST EXTENT PERMISSIBLE UNDER APPLICABLE LAW, THE SOFTWARE ELECTRONIC ARTS SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED TO YOU “AS IS,” WITH ALL FAULTS, WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, AND YOUR USE IS AT YOUR SOLE RISK.