The Scope of Traditional and Geometric Morphometrics for Inferences of Diet in Carnivorous Fossil Mammals Sergio Tarquini, M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of Large Terrestrial Carnivores on Pleistocene Ecosystems Blaire Van Valkenburgh, Matthew W

The impact of large terrestrial carnivores on SPECIAL FEATURE Pleistocene ecosystems Blaire Van Valkenburgha,1, Matthew W. Haywardb,c,d, William J. Ripplee, Carlo Melorof, and V. Louise Rothg aDepartment of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095; bCollege of Natural Sciences, Bangor University, Bangor, Gwynedd LL57 2UW, United Kingdom; cCentre for African Conservation Ecology, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth, South Africa; dCentre for Wildlife Management, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa; eTrophic Cascades Program, Department of Forest Ecosystems and Society, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331; fResearch Centre in Evolutionary Anthropology and Palaeoecology, School of Natural Sciences and Psychology, Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool L3 3AF, United Kingdom; and gDepartment of Biology, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708-0338 Edited by Yadvinder Malhi, Oxford University, Oxford, United Kingdom, and accepted by the Editorial Board August 6, 2015 (received for review February 28, 2015) Large mammalian terrestrial herbivores, such as elephants, have analogs, making their prey preferences a matter of inference, dramatic effects on the ecosystems they inhabit and at high rather than observation. population densities their environmental impacts can be devas- In this article, we estimate the predatory impact of large (>21 tating. Pleistocene terrestrial ecosystems included a much greater kg, ref. 11) Pleistocene carnivores using a variety of data from diversity of megaherbivores (e.g., mammoths, mastodons, giant the fossil record, including species richness within guilds, pop- ground sloths) and thus a greater potential for widespread habitat ulation density inferences based on tooth wear, and dietary in- degradation if population sizes were not limited. -

The Influence of Livestock Protection Dogs on Mesocarnivore

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Texas A&M Repository THE INFLUENCE OF LIVESTOCK PROTECTION DOGS ON MESOCARNIVORE ACTIVITY IN THE EDWARDS PLATEAU OF TEXAS A Thesis by NICHOLAS A. BROMEN Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Chair of Committee: John M. Tomeček Co-Chair of Committee: Nova J. Silvy Committee Member: Fred E. Smeins Head of Department: Michael P. Masser December 2017 Major Subject: Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences Copyright 2017 Nick Bromen ABSTRACT The use of livestock protection dogs (LPDs; Canis lupus familiaris) to deter predators from preying upon sheep and goat herds continues to increase across the United States. Most research regarding the efficacy of LPDs has been based on queries of rancher satisfaction with their performance, yet little is known regarding whether LPDs actually displace the predators they are commissioned to protect livestock from. Here, I examined whether the presence of LPDs amid livestock resulted in fewer observable detections of carnivores in pastures they occupied throughout 1 year on a ranch in central Texas. To detect and quantify the presence of carnivores across the ranch, a remote camera grid and scat transects were simultaneously surveyed to compare results produced between each method. Four LPDs were fitted with GPS collars to collect their positions and evaluate their occupancy across the ranch over time. These GPS collars also collected proximity data on a random sample of UHF collared sheep (n = 40) and goats (n = 20) to gauge the frequency to which the LPDs were near livestock. -

Size-Based Responses of Prey to Piscivore Exclusion in a Species-Rich Neotropical River

Ecology, 85(5), 2004,pp. 1311-1320 @ 2004 by the Ecological Society of America SIZE-BASED RESPONSES OF PREY TO PISCIVORE EXCLUSION IN A SPECIES-RICH NEOTROPICAL RIVER CRAIG A. LAYMAN! AND KIRK O. WINEMILLER Section of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences, 210 Nagle Hall, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas 77843-2258 USA Abstract. Characteristics used to group species, and thus generalize ecological inter': actions, can aid in constructing predictive models in species-rich food webs. We tested whether size could be used to predict a behavioral response of multiple prey species (n > 50) to exclusion of large-bodied fishes, including seven abundant piscivore species, in a lowland Neotropical river. A randomized block design (n = 6) included three experimental treatments constructed on sandbank habitats: large fish exclusion, cage control (barrier with gaps), and natural reference plot (no barrier). Exclosures prevented passage of all large- bodied fishes, but the mesh size allowed passage of prey fishes. After two weeks, exper- imental areas were sampled once during the day and once at night. Total abundance of prey fishes was not significantly different among treatments, and effects on specie~density were variable. Analyses based on fish size class, however, demonstrated significant size- based effects of large-fish exclusion. Abundance of medium fishes (40-110 mm) in exclu. sion treatments increased significantly relative to controls in day (248%) and night (91 %) samples, and this trend was apparent for many species (n > 13). Species density of medium fishes increased significantly in exclusion treatments. There was evidence of an intraspecific, size-dependent response for the three most common species. -

Photographic Evidence of a Jaguar (Panthera Onca) Killing an Ocelot (Leopardus Pardalis)

Received: 12 May 2020 | Revised: 14 October 2020 | Accepted: 15 November 2020 DOI: 10.1111/btp.12916 NATURAL HISTORY FIELD NOTES When waterholes get busy, rare interactions thrive: Photographic evidence of a jaguar (Panthera onca) killing an ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) Lucy Perera-Romero1 | Rony Garcia-Anleu2 | Roan Balas McNab2 | Daniel H. Thornton1 1School of the Environment, Washington State University, Pullman, WA, USA Abstract 2Wildlife Conservation Society – During a camera trap survey conducted in Guatemala in the 2019 dry season, we doc- Guatemala Program, Petén, Guatemala umented a jaguar killing an ocelot at a waterhole with high mammal activity. During Correspondence severe droughts, the probability of aggressive interactions between carnivores might Lucy Perera-Romero, School of the Environment, Washington State increase when fixed, valuable resources such as water cannot be easily partitioned. University, Pullman, WA, 99163, USA. Email: [email protected] KEYWORDS activity overlap, activity patterns, carnivores, interspecific killing, drought, climate change, Funding information Maya forest, Guatemala Coypu Foundation; Rufford Foundation Associate Editor: Eleanor Slade Handling Editor: Kim McConkey 1 | INTRODUCTION and Johnson 2009). Interspecific killing has been documented in many different pairs of carnivores and is more likely when the larger Interference competition is an important process working to shape species is 2–5.4 times the mass of the victim species, or when the mammalian carnivore communities (Palomares and Caro 1999; larger species is a hypercarnivore (Donadio and Buskirk 2006; de Donadio and Buskirk 2006). Dominance in these interactions is Oliveria and Pereira 2014). Carnivores may reduce the likelihood often asymmetric based on body size (Palomares and Caro 1999; de of these types of encounters through the partitioning of habitat or Oliviera and Pereira 2014), and the threat of intraguild strife from temporal activity. -

A Review of Planktivorous Fishes: Their Evolution, Feeding Behaviours, Selectivities, and Impacts

Hydrobiologia 146: 97-167 (1987) 97 0 Dr W. Junk Publishers, Dordrecht - Printed in the Netherlands A review of planktivorous fishes: Their evolution, feeding behaviours, selectivities, and impacts I Xavier Lazzaro ORSTOM (Institut Français de Recherche Scientifique pour le Développement eri Coopération), 213, rue Lu Fayette, 75480 Paris Cedex IO, France Present address: Laboratorio de Limrzologia, Centro de Recursos Hidricob e Ecologia Aplicada, Departamento de Hidraulica e Sarzeamento, Universidade de São Paulo, AV,DI: Carlos Botelho, 1465, São Carlos, Sï? 13560, Brazil t’ Mail address: CI? 337, São Carlos, SI? 13560, Brazil Keywords: planktivorous fish, feeding behaviours, feeding selectivities, electivity indices, fish-plankton interactions, predator-prey models Mots clés: poissons planctophages, comportements alimentaires, sélectivités alimentaires, indices d’électivité, interactions poissons-pltpcton, modèles prédateurs-proies I Résumé La vision classique des limnologistes fut de considérer les interactions cntre les composants des écosystè- mes lacustres comme un flux d’influence unidirectionnel des sels nutritifs vers le phytoplancton, le zoo- plancton, et finalement les poissons, par l’intermédiaire de processus de contrôle successivement physiqucs, chimiques, puis biologiques (StraSkraba, 1967). L‘effet exercé par les poissons plaiictophages sur les commu- nautés zoo- et phytoplanctoniques ne fut reconnu qu’à partir des travaux de HrbáEek et al. (1961), HrbAEek (1962), Brooks & Dodson (1965), et StraSkraba (1965). Ces auteurs montrèrent (1) que dans les étangs et lacs en présence de poissons planctophages prédateurs visuels. les conimuiiautés‘zooplanctoniques étaient com- posées d’espèces de plus petites tailles que celles présentes dans les milieux dépourvus de planctophages et, (2) que les communautés zooplanctoniques résultantes, composées d’espèces de petites tailles, influençaient les communautés phytoplanctoniques. -

Carnivore-Specific Stable Isotope Variables and Variation in The

458 Carnivore-specific stable isotope variables and variation in the foraging ecology of modern and ancient wolf populations: case studies from Isle Royale, Minnesota, and La Brea K. Fox-Dobbs, J.K. Bump, R.O. Peterson, D.L. Fox, and P.L. Koch Abstract: We use carbon and nitrogen isotope data collected from two North American gray wolf (Canis lupus L., 1758) populations (Isle Royale and northern Minnesota) to both calculate carnivore-specific isotopic variables and investigate wolf foraging ecology. The isotopic enrichments of 13C and 15N that occur between mammalian carnivores and their prey have not been well defined in modern populations. We use bone collagen from the Isle Royale National Park wolf, moose (Alces alces (L., 1758)), and beaver (Castor canadensis Kuhl, 1820) populations to determine trophic enrichment factors of 1.3% ± 0.6% for d13C and 4.6% ± 0.7% for d15N. We apply these carnivore-specific fractionation factors to a case study from the fossil record, and reconstruct the diets of late-Pleistocene dire wolves (Canis dirus (Leidy, 1858)) from the La Brea tar pits. We use the Minnesota wolf tissue (collagen, hair, muscle) isotopic data to estimate carnivore population subsample sizes needed to replicate the mean values of the whole population within one standard deviation. Finally, we compare the Isle Royale and Minnesota collagen and hair isotopic data to published d13C and d15N values for North Amer- ican gray wolf populations. We find that interpopulation differences in isotope variances provide insight into wolf foraging ecology. Re´sume´ : Nous utilisons des donne´es sur les isotopes de carbone et d’azote re´colte´es dans deux populations (Isle Royale et nord du Minnesota) de loups gris (Canis lupus L., 1758) pour calculer les variables isotopiques spe´cifiques aux carni- vores et aussi pour e´tudier l’e´cologie alimentaire des loups. -

Spatio-Temporal Coexistence of Sympatric Mesocarnivores with a Single Apex Carnivore in a fine-Scale Landscape

Global Ecology and Conservation 21 (2020) e00897 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Global Ecology and Conservation journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/gecco Original Research Article Spatio-temporal coexistence of sympatric mesocarnivores with a single apex carnivore in a fine-scale landscape Guojing Zhao a, b, c, d, e, 1, Haitao Yang a, b, c, d, e, 1, Bing Xie a, b, c, d, e, * Yinan Gong a, b, c, d, e, Jianping Ge a, b, c, d, e, Limin Feng a, b, c, d, e, a Northeast Tiger and Leopard Biodiversity National Observation and Research Station, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, 100875, China b National Forestry and Grassland Administration Key Laboratory for Conservation Ecology of Northeast Tiger and Leopard National Park, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, 100875, China c National Forestry and Grassland Administration Amur Tiger and Amur Leopard Monitoring and Research Center, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, 100875, China d Ministry of Education Key Laboratory for Biodiversity Science and Engineering, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, 100875, China e College of Life Sciences, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, 100875, China article info abstract Article history: Mesocarnivores uniquely and profoundly impact ecosystem function, structure, and dy- Received 23 July 2019 namics. Sympatric species tend to spatially and temporally partition limited resources to Received in revised form 22 December 2019 facilitate coexistence. We investigated the seasonal spatial and temporal cooccurrences Accepted 22 December 2019 among six mesocarnivores, the leopard cat (Prionailurus bengalensis), red fox (Vulpes vulpes), Asian badger (Meles leucurus), Siberian weasel (Mustela sibirica), masked palm Keywords: civet (Paguma larvata) and yellow-throated marten (Martes flavigula), as well as a single Camera trap apex predator (Northern Chinese leopard, Panthera pardus japonensis). -

The Early Hunting Dog from Dmanisi with Comments on the Social

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN The early hunting dog from Dmanisi with comments on the social behaviour in Canidae and hominins Saverio Bartolini‑Lucenti1,2*, Joan Madurell‑Malapeira3,4, Bienvenido Martínez‑Navarro5,6,7*, Paul Palmqvist8, David Lordkipanidze9,10 & Lorenzo Rook1 The renowned site of Dmanisi in Georgia, southern Caucasus (ca. 1.8 Ma) yielded the earliest direct evidence of hominin presence out of Africa. In this paper, we report on the frst record of a large‑sized canid from this site, namely dentognathic remains, referable to a young adult individual that displays hypercarnivorous features (e.g., the reduction of the m1 metaconid and entoconid) that allow us to include these specimens in the hypodigm of the late Early Pleistocene species Canis (Xenocyon) lycaonoides. Much fossil evidence suggests that this species was a cooperative pack‑hunter that, unlike other large‑sized canids, was capable of social care toward kin and non‑kin members of its group. This rather derived hypercarnivorous canid, which has an East Asian origin, shows one of its earliest records at Dmanisi in the Caucasus, at the gates of Europe. Interestingly, its dispersal from Asia to Europe and Africa followed a parallel route to that of hominins, but in the opposite direction. Hominins and hunting dogs, both recorded in Dmanisi at the beginning of their dispersal across the Old World, are the only two Early Pleistocene mammal species with proved altruistic behaviour towards their group members, an issue discussed over more than one century in evolutionary biology. Wild dogs are medium- to large-sized canids that possess several hypercarnivorous craniodental features and complex social and predatory behaviours (i.e., social hierarchic groups and pack-hunting of large vertebrate prey typically as large as or larger than themselves). -

The Role of Piscivores in a Species-Rich Tropical Food

THE ROLE OF PISCIVORES IN A SPECIES-RICH TROPICAL RIVER A Dissertation by CRAIG ANTHONY LAYMAN Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2004 Major Subject: Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences THE ROLE OF PISCIVORES IN A SPECIES-RICH TROPICAL RIVER A Dissertation by CRAIG ANTHONY LAYMAN Submitted to Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved as to style and content by: _________________________ _________________________ Kirk O. Winemiller Lee Fitzgerald (Chair of Committee) (Member) _________________________ _________________________ Kevin Heinz Daniel L. Roelke (Member) (Member) _________________________ Robert D. Brown (Head of Department) August 2004 Major Subject: Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences iii ABSTRACT The Role of Piscivores in a Species-Rich Tropical River. (August 2004) Craig Anthony Layman, B.S., University of Virginia; M.S., University of Virginia Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Kirk O. Winemiller Much of the world’s species diversity is located in tropical and sub-tropical ecosystems, and a better understanding of the ecology of these systems is necessary to stem biodiversity loss and assess community- and ecosystem-level responses to anthropogenic impacts. In this dissertation, I endeavored to broaden our understanding of complex ecosystems through research conducted on the Cinaruco River, a floodplain river in Venezuela, with specific emphasis on how a human-induced perturbation, commercial netting activity, may affect food web structure and function. I employed two approaches in this work: (1) comparative analyses based on descriptive food web characteristics, and (2) experimental manipulations within important food web modules. -

'Super Predator' Reduces Feeding Time in Large Carnivores

Downloaded from http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on July 24, 2017 Fear of the human ‘super predator’ rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org reduces feeding time in large carnivores Justine A. Smith1, Justin P. Suraci1,2, Michael Clinchy2, Ayana Crawford1, Devin Roberts2, Liana Y. Zanette2,† and Christopher C. Wilmers1,† Research 1Center for Integrated Spatial Research, Environmental Studies Department, University of California, Santa Cruz, CA 95064, USA Cite this article: Smith JA, Suraci JP, Clinchy 2Department of Biology, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada N6A 5B7 M, Crawford A, Roberts D, Zanette LY, Wilmers JAS, 0000-0001-8753-4061; JPS, 0000-0001-5952-2186; MC, 0000-0003-4691-3879; CC. 2017 Fear of the human ‘super predator’ LYZ, 0000-0003-2574-3452; CCW, 0000-0003-2063-1478 reduces feeding time in large carnivores. Proc. R. Soc. B 284: 20170433. Large carnivores’ fear of the human ‘super predator’ has the potential to alter their feeding behaviour and result in human-induced trophic cascades. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2017.0433 However, it has yet to be experimentally tested if large carnivores perceive humans as predators and react strongly enough to have cascading effects on their prey. We conducted a predator playback experiment exposing pumas to predator (human) and non-predator control (frog) sounds at puma feeding Received: 28 February 2017 sites to measure immediate fear responses to humans and the subsequent Accepted: 19 May 2017 impacts on feeding. We found that pumas fled more frequently, took longer to return, and reduced their overall feeding time by more than half in response to hearing the human ‘super predator’. -

Emeraid Feeding Guidelines

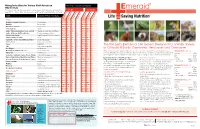

Mixing Instructions for Various North American *Scoops of Emeraid Mixed Wild Animals *Use either the large end of the scoop with 60 cc of warm water (103-110°F) or the small end of the Adults Juveniles e e e † e e e r r r e r r r o o o r o o o v v v o v v v i i i v i i i n n b i n n b Taxa Natural foods of adults r r c r r m a e is m a e Aves O C H P O C H Blackbirds, Grackles, Cowbirds Seeds, insects 6 0 0 3 1 0 Bluebirds Insects, fruits 0 2 0 0 2 0 Chickadees, Titmouse Insects, seeds 1.5 1.5 0 0 2 0 Doves, Pigeons Seeds 6 0 0 4.5 0.5 0 Ducks–Mallard, Canvasback, Coots, Gadwall Vegetation, seeds, insects, molluscs 6 0 0 6 0 0 Ducks–Goldeneye, Bufflehead, Scoter Insects, crustacea, molluscs 0 2 0 3 0 2 0 Ducks–Scaup, Ruddy Aquatic vegetation, insects, crustacea 4.5 0.5 0 3 3 1 0 Finches, Siskins, Crossbills Seeds 6 0 0 6 0 0 Gamebirds–Grouse, Quail, Pheasant, Turkey Seeds, some insects 6 0 0 4.5 0.5 0 Grebes, Loons Fish, crustacea, molluscs 0 2 0 3 0 2 0 Geese Vegetation 3 0 2 4.5 0 1 TThehe FFirstirst S Elementalemi-Eleme nDiettal DSystemiet Syst eDesignedm Design fored Criticallyfor a Wid eIll VExoticsariety Gulls Fish, crustacea, molluscs 0 2 0 3 0 2 0 Jays, Magpies Seeds, insects 6 0 0 3 1 0 oWillf Cther nextitic severelyally debilitated Ill Exo animaltic beC ana amazon,rnivo a ferretres or, Han eiguana?rbi vExoticor eanimals a nd OmEmeraidnivo Omnivoreres Insects, fruits, seeds 1.5 1.5 0 0 2 0 Will the next severely debilitated animal be an Amazon, a ferret or an iguana? Exotic animal veterinarians are EProteinmera id Omnivore 20% ® Fat 9.5% Nuthatches Insects, seeds 1.5 1.5 0 0 2 0 pisre sdesignedented wit hto d quicklyifficult e mprovideergenci elife-savings every day elemental. -

Isotopic Trophic Guild Structure of a Diverse Subtropical South American fish Community

Ecology of Freshwater Fish 2013: 22: 66–72 Ó 2012 John Wiley & Sons A/S Printed in Malaysia Á All rights reserved ECOLOGY OF FRESHWATER FISH Isotopic trophic guild structure of a diverse subtropical South American fish community Edward D. Burress1, Alejandro Duarte2, Michael M. Gangloff1, Lynn Siefferman1 1Biology Department, Appalachian State University, Boone, NC USA 2Seccio´n Zoologia Vertebrados, deptartamento de Ecologia y Evolucion, Facultad de Ciencias, Montevideo, Uruguay Accepted for publication July 25, 2012 Abstract – Characterization of food web structure may provide key insights into ecological function, community or population dynamics and evolutionary forces in aquatic ecosystems. We measured stable isotope ratios of 23 fish species from the Rio Cuareim, a fifth-order tributary of the Rio Uruguay basin, a major drainage of subtropical South America. Our goals were to (i) describe the food web structure, (ii) compare trophic segregation at trophic guild and taxonomic scales and (iii) estimate the relative importance of basal resources supporting fish biomass. Although community-level isotopic overlap was high, trophic guilds and taxonomic groups can be clearly differentiated using stable isotope ratios. Omnivore and herbivore guilds display a broader d13C range than insectivore or piscivore guilds. The food chain consists of approximately three trophic levels, and most fishes are supported by algal carbon. Understanding food web structure may be important for future conservation programs in subtropical river systems by identifying top predators, taxa that may occupy unique trophic roles and taxa that directly engage basal resources. Key words: carbon; nitrogen; niche; resource; food web For example, sucker-mouthed catfishes (Loricariidae) Introduction play important functional roles by modifying habitat Aquatic systems are often defined by the fish species (Power 1990) and consuming resources that are often they support.