Colour, Shape, and Music: the Presence of Thought Forms in Abstract Art Zoe Alderton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Painting from One of the World's Greatest Collectors Offered

Press Release For Immediate Release Melbourne 3 May 2016 John Keats 03 9508 9900 [email protected] Australian Painting from One of the World’s Greatest Collectors Offered for Auction Important Australian & International Art | Auction in Sydney 11 May 2016 Roy de Maistre 1894-1968, The Studio Table 1928. Estimate $60,000-80,000 A painting from the collection of one of world’s most renowned art collectors and patrons will be auctioned by Sotheby’s Australia on 11 May at the InterContinental Sydney. Roy de Maistre’s The Studio Table 1928 was owned by Samuel Courtauld founder of The Courtauld Institute of Art and The Courtauld Gallery, and donor of acquisition funds for the Tate, London and National Gallery, London. De Maistre was one of Australia’s early pioneers of modern art and The Studio Table (estimate $60,000-80,000, lot 127, pictured) provides a unique insight into the studio environment of one of Anglo-Australia’s greatest artists. 1 | Sotheby’s Australia is a trade mark used under licence from Sotheby's. Second East Auction Holdings Pty Ltd is independent of the Sotheby's Group. The Sotheby's Group is not responsible for the acts or omissions of Second East Auction Holdings Pty Ltd Geoffrey Smith, Chairman of Sotheby’s Australia commented: ‘Sotheby’s Australia is honoured to be entrusted with this significant painting by Roy de Maistre from The Samuel Courtauld Collection. De Maistre’s works are complex in origins and intricate in construction. Mentor to the young Francis Bacon, De Maistre remains one of Australia’s most influential and enigmatic artists, whose unique contribution to the development of modern art in Australia and Great Britain is still to be fully understood and appreciated.’ A leading exponent of Modernism and Abstraction in Australia, The Studio Table was the highlight of Roy de Maistre’s solo exhibition in Sydney in 1928. -

The Secret Doctrine Symposium

The Secret Doctrine Symposium Compiled and Edited by David P. Bruce THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY IN AMERICA P.O. Box 270, Wheaton, IL 60187-0270 www.theosophical.org © 2011 Introduction In creating this course, it was the compiler’s intention to feature some of the most com- pelling and insightful articles on The Secret Doctrine published in Theosophical journals over the past several decades. Admittedly, the process of selecting a limited few from the large number available is to some extent a subjective decision. One of the criteria used for making this selection was the desire to provide the reader with a colorful pastiche of commentary by respected students of Theosophy, in order to show the various avenues of approach to Mme. Blavatsky’s most famous work. The sequence of the articles in the Symposium was arranged, not chronologically, nor alphabetically by author, but thematically and with an eye to a sense of balance. While some of the articles are informational, there are also those that are inspirational, historical, and instructional. It is hoped that the Symposium will encourage, inspire, and motivate the student to begin a serious and sustained exploration of this most unusual and important Theosophical work. Questions have been added to each of the articles. When referring to a specific quote or passage within the article, the page number and paragraph are referenced. For instance, (1.5) indicates the fifth paragraph on page one; (4.2) indicates the second paragraph on page four. A page number followed by a zero, i.e ., (25.0) would indicate that something is being discussed in the paragraph carried over from the previous page, in this case, page 24. -

Important Australian and Aboriginal

IMPORTANT AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ART including The Hobbs Collection and The Croft Zemaitis Collection Wednesday 20 June 2018 Sydney INSIDE FRONT COVER IMPORTANT AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ART including the Collection of the Late Michael Hobbs OAM the Collection of Bonita Croft and the Late Gene Zemaitis Wednesday 20 June 6:00pm NCJWA Hall, Sydney MELBOURNE VIEWING BIDS ENQUIRIES PHYSICAL CONDITION Tasma Terrace Online bidding will be available Merryn Schriever OF LOTS IN THIS AUCTION 6 Parliament Place, for the auction. For further Director PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE East Melbourne VIC 3002 information please visit: +61 (0) 414 846 493 mob IS NO REFERENCE IN THIS www.bonhams.com [email protected] CATALOGUE TO THE PHYSICAL Friday 1 – Sunday 3 June CONDITION OF ANY LOT. 10am – 5pm All bidders are advised to Alex Clark INTENDING BIDDERS MUST read the important information Australian and International Art SATISFY THEMSELVES AS SYDNEY VIEWING on the following pages relating Specialist TO THE CONDITION OF ANY NCJWA Hall to bidding, payment, collection, +61 (0) 413 283 326 mob LOT AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 111 Queen Street and storage of any purchases. [email protected] 14 OF THE NOTICE TO Woollahra NSW 2025 BIDDERS CONTAINED AT THE IMPORTANT INFORMATION Francesca Cavazzini END OF THIS CATALOGUE. Friday 14 – Tuesday 19 June The United States Government Aboriginal and International Art 10am – 5pm has banned the import of ivory Art Specialist As a courtesy to intending into the USA. Lots containing +61 (0) 416 022 822 mob bidders, Bonhams will provide a SALE NUMBER ivory are indicated by the symbol francesca.cavazzini@bonhams. -

“History of Education Society Bulletin” (1985)

History of Education Society Bulletin (1985) Vol. 36 pp 52 -54 MONTESSORI WAS A THEOSOPHIST Carolie Wilson Dept. of Education, University of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia In October 1947 Time magazine reported that world famous education- ist Dr. Maria Montessori, though 'almost forgotten', was none the less very much alive in India where she was continuing to give lectures in the grounds of the Theosophical Society's magnificent estate at Adyar on the outskirts of Madras. 1 Accompanied by her son Mario, Montessori had gone to India at the invitation of Theosophical Society President, George Arundale, in No- vember 1939 and had been interned there as an 'enemy alien' when Italy en- tered the Second World War in June 1940. The Dottoressa was permitted however, to remain at Adyar to continue her teacher training courses and later to move to a more congenial climate in the hills at Kodaikanal. 2 At the end of the War she made a short visit to Europe but returned to India to undertake the first teacher training course at the new Arundale Montessori Training Centre.3 The Centre was established as a memorial to former Theosophi- cal Society President, Dr. Annie Besant, whose centenary was being celebrat- ed at Adyar in October 1947.4 In view, no doubt, of her continued residence at Adyar and the gener- ous support the Theosophical Society extended to Montessori and Mario during the War years, the Dottoressa was asked on one occasion under the shade of the famous giant banyan tree at Adyar, whether she had in fact become a Theosophist. -

One 1 Mark Question. One 4 Mark Question. One 6 Mark Question

10. Rukmini Devi Arundale. One 1 mark question. One 4 mark question. One 6 mark question. Content analysis About Rukmini Devi Arundale. Born on 29‐02‐1904 Father Neelakantha StiSastri Rukmini Devi Arundale Rukmini Devi Liberator of classical dance. India’s cultural queen. Rukmini Devi Fearless crusader for socilial c hange. Champion of vegetarianism. Andhra art of vegetable-dyed Kalmakari Textile crafts like weaving silk an d cotton a la (as prepared in) Kanchipuram Banyan tree at Adyar Rukmini Devi The force that shaped the future of Rukmini Devi Anna Pavlova Anna Pavlova Wraith-like ballerina (Wraith-like =otherworldly) Her meeting with Pavlova. First meeting : In 1924, in London at the Covent Gardens. Her meeting with Pavlova. Second meeting: Time : At the time of annual Theosophical Convention at Banaras. Place : Bombay - India. The warm tribute of Pavlova Rukmini Devi: I wish I could dance like you, but I know I never can. The warm tribute of Pavlova Anna Pavlova:NonoYoumust: No, no. You must never say that. You don’t have to dance, for if you just walk across the stage, it will be enouggph. People will come to watch you do just that. Learning Sadir. She learnt Sadir, the art of Devadasis . Hereditary guru : Meenakshisundaram Pillai. Duration: Two years. First performance At the International Theosophical Conference Under a banyan tree In 1935. reaction Orthodox India was shocked . The first audience adored her revelatory debut. The Bishop of Madras confessed that he felt like he had attended a benediction. Liberating the Classical dance. Changes made to Sadir. Costume and jewellery were of good taste. -

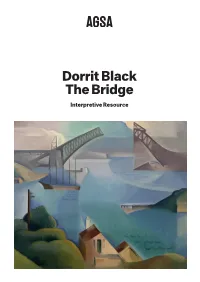

Dorrit Black the Bridge

Dorrit Black The Bridge Interpretive Resource Australian modernist Dorrit Black The Bridge, 1930 was Australia’s first Image (below) and image detail (cover) (1891–1951) was a painter and printmaker cubist landscape, and demonstrated a Dorrit Black, Australia, who completed her formal studies at the new approach to the painting of Sydney 1891–1951, The Bridge, 1930, Sydney, oil on South Australian School of Arts and Crafts Harbour. As the eye moves across the canvas on board, 60.0 x around 1914 and like many of her peers, picture plane, Black cleverly combines 81.0 cm; Bequest of the artist 1951, Art Gallery of travelled to Europe in 1927 to study the the passage of time in a single painting. South Australia, Adelaide. contemporary art scene. During her two The delicately fragmented composition years away her painting style matured as and sensitive colour reveals her French she absorbed ideas of the French cubist cubist teachings including Lhote’s dynamic painters André Lhote and Albert Gleizes. compositional methods and Gleizes’s vivid Black returned to Australia as a passionate colour palette. Having previously learnt to supporter of Cubism and made significant simplify form through her linocut studies contribution to the art community by in London with pioneer printmaker, Claude teaching, promoting and practising Flight, all of Black’s European influences modernism, initially in Sydney, and then in were combined in this modern response to Adelaide in the 1940s. the Australian landscape. Dorrit Black – The Bridge, 1930 Interpretive Resource agsa.sa.gov.au/education 2 Early Years Primary Responding Responding What shapes can you see in this painting? What new buildings have you seen built Which ones are repeated? in recent times? How was the process documented? Did any artists capture The Sydney Harbour Bridge is considered a this process? Consider buildings you see national icon – something we recognise as regularly, which buildings do you think Australian. -

The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon the Theosophical Seal a Study for the Student and Non-Student

The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon The Theosophical Seal A Study for the Student and Non-Student by Arthur M. Coon This book is dedicated to all searchers for wisdom Published in the 1800's Page 1 The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon INTRODUCTION PREFACE BOOK -1- A DIVINE LANGUAGE ALPHA AND OMEGA UNITY BECOMES DUALITY THREE: THE SACRED NUMBER THE SQUARE AND THE NUMBER FOUR THE CROSS BOOK 2-THE TAU THE PHILOSOPHIC CROSS THE MYSTIC CROSS VICTORY THE PATH BOOK -3- THE SWASTIKA ANTIQUITY THE WHIRLING CROSS CREATIVE FIRE BOOK -4- THE SERPENT MYTH AND SACRED SCRIPTURE SYMBOL OF EVIL SATAN, LUCIFER AND THE DEVIL SYMBOL OF THE DIVINE HEALER SYMBOL OF WISDOM THE SERPENT SWALLOWING ITS TAIL BOOK 5 - THE INTERLACED TRIANGLES THE PATTERN THE NUMBER THREE THE MYSTERY OF THE TRIANGLE THE HINDU TRIMURTI Page 2 The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon THE THREEFOLD UNIVERSE THE HOLY TRINITY THE WORK OF THE TRINITY THE DIVINE IMAGE " AS ABOVE, SO BELOW " KING SOLOMON'S SEAL SIXES AND SEVENS BOOK 6 - THE SACRED WORD THE SACRED WORD ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Page 3 The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon INTRODUCTION I am happy to introduce this present volume, the contents of which originally appeared as a series of articles in The American Theosophist magazine. Mr. Arthur Coon's careful analysis of the Theosophical Seal is highly recommend to the many readers who will find here a rich store of information concerning the meaning of the various components of the seal Symbology is one of the ancient keys unlocking the mysteries of man and Nature. -

Making Modernism Student Resource

STUDENT RESOURCE INTRODUCTION The time of Georgia O’Keeffe, Margaret Preston and Grace Cossington Smith was characterised by scientific discovery, war, rapid urbanisation, engineering and industrialisation. Rather than working toward tonal modelling and ‘imitative drawing’ techniques, these women artists were driven toward abstraction by theories about colour and distortion initiated by the Fauvists in Europe, as well as by their own fascination with the depiction of light. Arthur Wesley Dow’s design exercises — influenced by Japanese aesthetics (Orientalism) that aimed to achieve harmony using notan, or ‘dark and light’ — were being taught around the world, including to O’Keeffe at a Georgia O’Keeffe / Ram’s Head, Blue Morning Glory (detail) 1938 / Gift of The Burnett Foundation 2007 / University of Virginia summer school; here in Australia, Collection: Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe / © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum Preston was reading about them. 1, 2 BEFORE VISIT ‘ Do not go where the path may RESEARCH – What is Modernism? Write a definition lead, go instead where there that considers the following terms: rapid change, is no path and leave a trail.’ world view, transportation, industrialisation, innovation, experimentation, rejecting tradition, realism, abstraction. Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–82), North American essayist and poet Locate on maps the cities, regions and other places significant to O’Keeffe, Preston and Cossington Smith, including New Mexico, Sydney Harbour and England. DEVELOP – Use Google Earth to find and take screen ‘ Lasting art is endlessly interesting shots of these locations and the vehicles in use at the time. because its meaning is constantly remade by each generation, by each REFLECT – Consider the impact of travel on artists, individual viewer.’ seeing new countries and landscapes for the first time. -

The Science of Spirituality

THE SCIENCE OF SPIRITUALITY By Ianthe Hoskins THE BLAVATSKY LECTURE delivered at the Annual Convention of The Theosophical Society in England, at Besant Hall, London, May 28th, 1950. As the Theosophical Society celebrates this year the seventy-fifth anniversary of its founding, occasions will not be wanting for the review of its history and for some appraisal of its achievements. Without entering into historical particulars, which are amply recorded elsewhere, it may be safely stated that certain currents of thought which are noticeable in the world of today trace their origin or their wide develop- ment to the Theosophical movement. The similarities between the great religions of the world have become common knowledge among educated people; the doctrine of reincarnation is an accepted theme in Western literature; the problem of survival has passed from the field of popular superstition to that of academic research; symbolism, astrology, telepathy, spiritual healing, all have their serious students and a significant body of literature; the Western reader may now have direct access to oriental thought through the commentaries and translations of many sacred and philosophical texts. Furthermore, individual Theosophists have made notable contributions to progress in the varied fields of religion, science, art, literature, education, politics, and human welfare. Indeed, Theosophical thought has been productive of such diverse expressions that one may easily lose sight of the principles which they attempt to embody. While, therefore, we may gain profit and inspiration from the review of the past, it is of the first importance that we should continually look beyond the superficial and transitory to the essential elements of the Theosophical system. -

Ocean to Outback: Australian Landscape Painting 1850–1950

travelling exhibition Ocean to Outback: Australian landscape painting 1850–1950 4 August 2007 – 3 May 2009 … it is continually exciting, these curious and strange rhythms which one discovers in a vast landscape, the juxtaposition of figures, of objects, all these things are exciting. Add to that again the peculiarity of the particular land in which we live here, and you get a quality of strangeness that you do not find, I think, anywhere else. Russell Drysdale, 19601 From the white heat of our beaches to the red heart of 127 of the 220 convicts on board died.2 Survivors’ accounts central Australia, Ocean to Outback: Australian landscape said the ship’s crew fired their weapons at convicts who, in painting 1850–1950 conveys the great beauty and diversity a state of panic, attempted to break from their confines as of the Australian continent. Curated by the National Gallery’s the vessel went down. Director Ron Radford, this major travelling exhibition is The painting is dominated by a huge sky, with the a celebration of the Gallery’s twenty-fifth anniversary. It broken George the Third dwarfed by the expanse. Waves features treasured Australian landscape paintings from the crash over the decks of the ship while a few figures in the national collection and will travel to venues throughout each foreground attempt to salvage cargo and supplies. This is Australian state and territory until 2009. a seascape that evokes trepidation and anxiety. The small Encompassing colonial through to modernist works, the figures contribute to the feeling of human vulnerability exhibition spans the great century of Australian landscape when challenged by the extremities of nature. -

Grace Cossington Smith

Grace Cossington Smith A RETROSPECTIVE EXHIBITION Proudly sponsored by This exhibition has been curated by Deborah Hart, Senior Curator, Australian Paintings and Sculpture at the National Gallery of Australia. Booking details Entry $12 Members and concessions $8 Entry for booked school groups and students under 16 is free Online teachers’ resources Visit nga.gov.au to download study sheets that can be used with on-line images – key works have been selected and are accompanied by additional text. Other resources available The catalogue to the exhibition: Grace Cossington Smith (a 10% discount is offered for schools’ purchases) Available from the NGA shop. Phone 1800 808 337 (free call) or 02 6240 6420, email [email protected], or shop online at ngashop.com.au Audio tour Free children’s trail Postcards, cards, bookmarks and posters Venues and dates National Gallery of Australia, Canberra 4 March – 13 June 2005 Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide 29 July – 9 October 2005 Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney 29 October 2005 – 15 January 2006 Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane 11 February – 30 April 2006 nga.gov.au/CossingtonSmith The National Gallery of Australia is an Australian Government Agency GRACE COSSINGTON SMITH EDUCATION RESOURCE Teachers’ notes Grace Cossington Smith (1892–1984) is one of Australia’s most important artists; a brilliant colourist, she was one of this country’s first Post-Impressionsts. She is renowned for her iconic urban images and radiant interiors. Although Cossington Smith was keenly attentive to the modern urban environment, she also brought a deeply personal, intimate response to the subjects of her art. -

The Secret Doctrine Symposium

The Secret Doctrine Symposium Compiled and Edited by David P. Bruce THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY IN AMERICA P.O. Box 270, Wheaton, IL 60187-0270 www.theosophical.org © 2011 This page was intentionally left blank. Introduction In creating this course, it was the compiler’s intention to feature some of the most com- pelling and insightful articles on The Secret Doctrine published in Theosophical journals over the past several decades. Admittedly, the process of selecting a limited few from the large number available is to some extent a subjective decision. One of the criteria used for making this selection was the desire to provide the reader with a colorful pastiche of commentary by respected students of Theosophy, in order to show the various avenues of approach to Mme. Blavatsky’s most famous work. The sequence of the articles in the Symposium was arranged, not chronologically, nor alphabetically by author, but thematically and with an eye to a sense of balance. While some of the articles are informational, there are also those that are inspirational, historical, and instructional. It is hoped that the Symposium will encourage, inspire, and motivate the student to begin a serious and sustained exploration of this most unusual and important Theosophical work. Questions have been added to each of the articles. When referring to a specific quote or passage within the article, the page number and paragraph are referenced. For instance, (1.5) indicates the fifth paragraph on page one; (4.2) indicates the second paragraph on page four. A page number followed by a zero, i.e ., (25.0) would indicate that something is being discussed in the paragraph carried over from the previous page, in this case, page 24.