Will 'Dr Death' Receive a Fair Trial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surgical News May 2013 / Page 3

Surgicalthe royaL a ustraLasian News CoLLege of surgeons May 2013 Vol: 12 No:10 The Golden Nov/Dec Scalpel games 2011 - a test of surgical skill Value of the Audit Improving patient outcomes The College of Surgeons of Australia and New Zealand c ntents 10 Alcohol-fuelled violence Why we need to talk about it 16 Global Burden of Surgical Disease How surgeons can advance the agenda 18 A test of skill Medics compete in surgical battle of skills 22 Medico-Legal The ongoing saga of Jayant Patel 12 6 Relationships & Advocacy 22 Your Practice Card 8 Surgical Snips A new web facility for 14 Poison’d Chalice members 17 Dr BB G-loved 28 PD Workshops 25 International 33 Case Note Review Development 37 Curmudgeon’s Corner Continuing a vision in the 46 Book Club Pacific 26 Successful Scholar Ajay Iyengar’s research UpToDate® with heart To learn more or to 32 Morbidity Audit and Logbook Tool subscribe risk-free, visit This key tool continues learn.uptodate.com/UTD improvement for Fellows Or call +1-781-392-2000. Patients don’t just expect you to have all the right answers. 18 34 They expect you to have them right now. Fortunately, there’s SurgicalTHE ROYAL AUSTRALASIAN News COLLEGE OF SURGEONS MAY 2013 Vol: 12 No:10 UpToDate, the only reliable clinical resource that anticipates your The Golden Nov/Dec Correspondence to Surgical News should be sent to: Scalpel games 2011 - a test of surgical skill questions, then helps you find accurate answers quickly – often in [email protected] Letters to the Editor should be sent to: [email protected] the time it takes to go from one patient to another. -

An Analysis of the Failed Employee Voice System at the Bundaberg Hospital

Fatal consequences: an analysis of the failed employee voice system at the Bundaberg Hospital Author Wilkinson, Adrian, Townsend, Keith, Graham, Tina, Muurlink, Olav Published 2015 Journal Title Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources Version Accepted Manuscript (AM) DOI https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12061 Copyright Statement © 2015 Australian Human Resources Institute. This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Fatal consequences: an analysis of the failed employee voice system at the Bundaberg Hospital, Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, Volume 53, Issue 3, pages 265–280, 2015 which has been published in final form at http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12061. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving (http://olabout.wiley.com/WileyCDA/Section/id-828039.html) Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/157963 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Fatal Consequences: An analysis of the failed employee voice system at the Bundaberg Hospital ABSTRACT In this paper we discuss the failure of the employee voice system at the Bundaberg Base Hospital (BBH) in Australia. Surgeon Jayant Patel who was arrested over the deaths of patients on whom he operated when he was the Director of Surgery at the Hospital. Our interest is in the reasons the established employee voice mechanisms failed when employees attempted to bring to the attention of managers serious issues. Our data is based on an analysis of the sworn testimonies of participants who participated in two inquiries concerning these events. An analysis of the events with a particular focus on the failings of the voice system is presented. -

The Whistleno. 68, October 2011

“All that is needed for evil to prosper is for people of good will to do nothing”—Edmund Burke The Whistle No. 68, October 2011 Newsletter of Whistleblowers Australia “As part of my treatment, I need a nurse with a whistle.” Media watch O’Farrell steps in “I conclude that the justice of the Top court backs case requires that the state, the suc- for whistleblower cessful party, be entitled to its costs,” whistleblowers Britt Smith and Adam Bennett he said. Alexander Bratersky Australian Associated Press Ms Sneddon told the media she was Moscow Times, 1 July 2011 3 August 2011 facing the prospect of severe financial hardship because of the decision. The Constitutional Court on Thursday THE whistleblower in the Milton “It was supposed to be compensa- ruled that state employees cannot be Orkopoulos child sex case won’t have tion. How does that compensate what I punished for engaging in whistle- to pay the state’s legal costs after NSW have gone through, that I could be on blowing activities against their superi- Premier Barry O’Farrell stepped in to medication for life,” she told Fairfax ors. The court based its ruling on the save the woman he calls a “hero.” Radio Network. case of two state employees, a police Mr O’Farrell announced the bailout Then came the surprise twist. Mr officer and tax inspector, who both for Gillian Sneddon hours after a NSW O’Farrell announced just before 3pm were fired for criticizing their bosses. Supreme Court judge ruled against her to parliament that the state would pick “A state employee might express his in the costs decision on Wednesday. -

Victoria's Legislative Council Inquires

STICKING UP FOR VICTORIA? — VICTORIA’S LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL INQUIRES INTO THE PERFORMANCE OF THE AUSTRALIAN HEALTH PRACTITIONER REGULATION AGENCY DR GABRIELLE WOLF* This article analyses the report of the Victorian Legislative Council’s Legal and Social Issues Legislation Committee (‘Committee’) from its Inquiry into the Performance of the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA). AHPRA is a national body that provides administrative support for the National Registration and Accreditation Scheme (NRAS), under which practitioners in 14 health professions across Australia are regulated. The article considers the Committee’s fi ndings and recommendations in light of the impetuses for the creation of the NRAS, as well as the structure and implementation of the NRAS and AHPRA. It is argued that that the value of the Committee’s report is confi ned to its identifi cation of important issues concerning the NRAS and AHPRA that, in the near future, will require a more critical and comprehensive investigation than the Committee undertook. I INTRODUCTION Two scandals in the fi rst years of the 21stt century eroded Australians’ confi dence in their system of regulating health practitioners. Dr Graeme Reeves and Dr Jayant Patel were charged with committing heinous crimes against patients while they were employed in hospitals and registered as medical practitioners by the Medical Boards of New South Wales and Queensland respectively. The only charges ultimately sustained against Patel related to his fraudulent representations to his registration body. Nevertheless, public outrage and government alarm in response to the original charges against Patel and to the events surrounding Reeves led to several inquiries into the cracks in the health system through which these practitioners had fallen. -

It / /Ja Member: 1

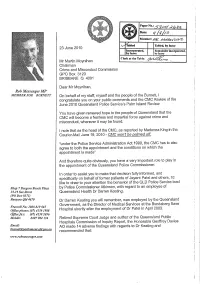

Paper No.: Date: it / /ja Member: 1 abled Tabled, by leave 23 June 2010 Incorporated, Remainder incorporated, by leave by leave Clerk at the Table: Mr Martin Moynihan Chairman Crime and Misconduct Commission GPO Box 3123 BRISBANE Q 4001 Dear Mr Moynihan, Rob Messenger MP MEMBER FOR B URNETT On behalf of my staff, myself and the people of the Burnett, I congratulate you on your public comments and the CMC Review of the June 2010 Queensland Police Service's Palm Island Review. You have given renewed hope to the people of Queensland that the CMC will become a fearless and impartial force against crime and misconduct, wherever it may be found. I note that as the head of the CMC, as reported by Madonna King in the Courier-Mail June 19, 2010.. CMG won't be palmed off "under the Police Service Administration Act 1990, the CIVIC has to also agree to both the appointment and the conditions on which the appointment is made" And therefore quite obviously, you have a very important role to play in the appointment of the Queensland Police Commissioner. In order to assist you to make that decision fully informed, and specifically on behalf of former patients of Jayent Patel and others, I'd like to draw to your attention the behavior of the QLD Police Service lead Strop 7Bargara Beacli -Plaza by Police Commissioner Atkinson, with regard to an employee of 15-19 See Street Queensland Health Dr Darren Keating. (PO Box 8371) Bargara Q1d4670 Dr Darren Keating you will remember, was employed by the Queensland Government, as the Director of Medical Services at the Bundaberg Base Freecall No. -

Legislative Council

8037 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Wednesday 4 June 2008 __________ The President (The Hon. Peter Thomas Primrose) took the chair at 11.00 a.m. The President read the Prayers. ENVIRONMENTAL PLANNING AND ASSESSMENT AMENDMENT BILL 2008 BUILDING PROFESSIONALS AMENDMENT BILL 2008 STRATA MANAGEMENT LEGISLATION AMENDMENT BILL 2008 Bills received, and read a first time and ordered to be printed on motion by the Hon. Tony Kelly, on behalf of the Hon. Michael Costa. Motion by The Hon. Tony Kelly agreed to: That standing orders be suspended to allow the passing of the bills through all their remaining stages during the present or any one sitting of the House. Second reading set down as an order of the day for a later hour. CHINA EARTHQUAKE Motion by Reverend the Hon. Fred Nile agreed to: That this House: (a) recognises the human tragedy that is unfolding in the People's Republic of China, (b) expresses its sympathies to the victims of the earthquake in Sichuan Province, China, and (c) calls on State and Federal governments to offer, where practical, all available assistance to those suffering as a result of this disaster. STANDING COMMITTEE ON STATE DEVELOPMENT Government Response to Report The Hon. John Della Bosca tabled the Government's response to report No. 32, entitled "Aspects of Agriculture", dated 28 November 2007. Ordered to be printed on motion by the Hon. John Della Bosca. UNPROCLAIMED LEGISLATION The Hon. Eric Roozendaal tabled a list detailing all legislation unproclaimed 90 calendar days after assent as at 3 June 2008. PETITIONS Cooma Hospital Kidney Dialysis Service Petition requesting the provision of a kidney dialysis service for patients in the Cooma region, received from the Hon. -

Queensland July to December 2005

304 Political Chronicles Queensland July to December 2005 PAUL D. WILLIAMS Grth University Observers of Queensland politics could be forgiven for thinking only one issue occupied the state's public sphere in the latter half of 2005: the management (or mismanagement) of health policy. Indeed, the allegations that an allegedly negligent, overseas-trained surgeon caused numerous patient deaths at Bundaberg Hospital (first raised in April 2005 — see previous chronicle) were so convulsive in their effect on the public mood that we may remember 2005's "Dr Death" saga as the principal turning point downwards in the electoral fortunes of Premier Peter Beattie. Moreover, damaging accusations of a "culture" of secrecy within Queensland Health that obfuscated evidence of malpractice directly or indirectly spawned a series of significant events, including four inquiries (of which three were judicial), a ministerial dismissal, two lost by-elections, a reformed Liberal-National coalition and, of course, a collapse in the government's and the Premier's public opinion leads. The Economy The state of the Queensland economy, while generally good, was perhaps less sanguine than many had hoped. While unemployment mid-year stood at just 3.9 per cent, then the second lowest in the nation (Courier- Mail, 8 July 2006), by year's close it once again had climbed toward 5 per cent (http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs%40.nsf/mf/6202.0) . Inflation, too, proved challenging, with the consumer price index increasing 0.8 percentage points in the December quarter (http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/ abs%40.nsf/mf/6401.0). -

Bundaberg Hospital Commission of Inquiry Interim Report of 10 June

Bundaberg Hospital Commission of Inquiry Interim Report of 10 June, 2005 Commissioner: Anthony Morris QC Deputy Commissioners: Sir Llewellyn Edwards AC, Margaret Vider RN Counsel Assisting: David Andrews SC, Errol Morzone, Damien Atkinson Secretary: David Groth Level 9, Brisbane Magistrates Court, 363 George Street, Brisbane Qld 4000 PO Box 13147, George Street Qld 4003 Telephone: 07 3109 9150 Facsimile: 07 3109 9151 Email: [email protected] Website: www.bhci.qld.gov.au BUNDABERG HOSPITAL COMMISSION OF INQUIRY - IN TERIM REPORT OF 10 JUNE, 2005 – PAGE 2 OF 43 PAGES SCOPE OF THIS INTERIM REPORT 1. This Interim Report is made pursuant to section 31 of the Commissions of Inquiry Act 1950, which provides: A commission may, at the discretion of the chairperson, make any separate reports, whether interim or final, and any separate recommendations concerning any of the subject matters of its inquiry. 2. The purpose of this Interim Report is solely to bring to the attention of the Governor in Council, through the Honourable the Premier and Minister for Trade, in accordance with the Terms of Reference (“ToR”), matters which have come to the attention of the Commission during the course of evidence in the period of 2 weeks commencing 23 May 2005, with reference to: 2.1 recommended legislative changes in relation to the Medical Practitioners Registration Act 2001 (“the Registration Act”); 2.2 recommended administrative changes regarding the process for declaring “areas of need” under section 135 of the Registration Act; and 2.3 potential grounds for the prosecution of JAYANT MUKUNDRAY PATEL (“Patel”) for certain offences under the Criminal Code in connection with his registration as a medical practitioner by the Medical Board of Queensland (“the Board”) under the Registration Act, his employment at the Bundaberg Base Hospital (“BBH”), and surgery performed by him at BBH. -

On the Politics of Ignorance in Nursing and Healthcare

Downloaded by [New York University] at 09:35 13 September 2016 On the Politics of Ignorance in Nursing and Healthcare Ignorance is mostly framed as a void, a gap to be filled with appropriate knowledge. In nursing and healthcare, concerns about ignorance fuel searches for knowledge expected to bring certainty to care provision, preventing risk, accidents or mistakes. This unique volume turns the focus on ignorance as something productive in itself, and works to understand how ignorance and its operations shape what we do and do not know. Focusing explicitly on nursing practice and its organisation within con- temporary health settings, Amélie Perron and Trudy Rudge draw on con- temporary interdisciplinary debates to discuss social processes informed by ignorance, ignorance’s temporal and spatial boundaries, and how ignorance defines what can be known by specific groups with differential access to power and social status. Using feminist, postcolonial and historical analyses, this book challenges dominant conceptualisations and discusses a range of ‘non- knowledges’ in nursing and health work, including uncertainty, abjection, denial, deceit and taboo. It also explores the way dominant research and managerial practices perpetuate ignorance in healthcare organisations. In health contexts, productive forms of ignorance can help to future-proof understandings about the management of healthy/sick bodies and those caring for them. Linking these considerations to nurses’ approaches to chal- lenges in practice, this book helps to unpack the power situated in the use of ignorance, and pays special attention to what is safe or unsafe to know, from both individual and organisational perspectives. On the Politics of Ignorance in Nursing and Healthcare is an innovative Downloaded by [New York University] at 09:35 13 September 2016 read for all students and researchers in nursing and the health sciences inter- ested in understanding more about transactions between epistemologies, knowledge-building practices and research in the health domain. -

Health Law Update

HEALTH LAW UPDATE August 2011 – Cases, News, Views & Research ADDRESS LEVEL 4, TOOWONG TOWER • Cardiotocographs – problematic for clinicians and judges 9 SHERWOOD ROAD,TOOWONG • Dr Patel, continued • Limitations of the peer professional practice defence BRISBANE, QUEENSLAND • Patient documentation AUSTRALIA • Gen-Y nurses tipping the balance of power CORRESPONDENCE PO BOX 82, TOOWONG CAUSATION AND SUSPICIOUS CTG TRACES QUEENSLAND, 4066 Case note McCoy v East Midlands Strategic Health AUSTRALIA Authority [2011] EWHC 38 (QB) This decision was delivered on 18 January 2011 by the Honourable Mrs Justice TELEPHONE Slade in the Queen’s Bench Division of the High Court of England and Wales. 07 3371 1066 BACKGROUND +61 7 3371 1066 The 17 year old claimant was born on 22 March 1993 at 39 weeks gestation in poor condition, and now suffers from diplegic cerebral palsy (a brain injury effecting contralateral limbs) and learning difficulties. Damages were claimed in clinical negligence, pursuant to section 1 of the Congenital Disabilities (Civil FACSIMILE Liability) Act 1976. 07 3371 7803 On 17 March 1993, the claimant’s mother (Ms Jones) attended Kettering General Hospital for monitoring after complaining of reduced fetal movements. +61 7 3371 7803 Ms Jones was given a cardiotocograph (‘CTG’) scan by Dr Lukshumeyah (‘a Staff Grade Obstetrician’), who later concluded the CTG trace was ‘satisfactory’, and sent Ms Jones home with a kick chart to record fetal movements. E-MAIL The claimant contended that Dr Lukshumeyah negligently interpreted the CTG scan. It was argued that as a result of Dr Lukshumeyah’s ‘satisfactory’ finding, [email protected] no further scans were undertaken, which would have likely shown a similar or worse fetal heart pattern, an indication of hypoxia. -

Factors in the Bundaberg Base Hospital Surgical

73 Harvey K and Faunce T “A Critical Analysis of Overseas-Trained Doctor (OTD) Factors in the Bundaberg Base Hospital Surgical Inquiry” in Freckelton I (ed) Regulating Health Practitioners, Law in Context Series Federation Press Sydney 2006; 23(2):73-91 A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF OVERSEAS-TRAINED DOCTOR (“OTD”) FACTORS IN THE BUNDABERG BASE HOSPITAL SURGICAL INQUIRY KARINA HARVEY* and THOMAS FAUNCE** *BA/LLB (Hons), Legal Officer, Australian Government Attorney-General’s Department ** BA/LLB (Hons) BMed PhD, Senior Lecturer Law Faculty and Medical School Australian National University Abstract This article explores one of the most intriguing and hitherto largely unexplored aspects of healthcare quality and safety investigations in Australia: the role of a protagonist’s status as an overseas-trained doctor (“OTD”). The topic is controversial, not the least because of the growing importance of OTDs in maintaining basic health services in some areas of Australia, but also due to the difficulty of teasing genuine quality and safety problems in this context from possible racial or xenophobic concerns. As a case study, we will explore the problems associated with Dr Jayant Patel at the Bundaberg Base Hospital (“BBH”) in Queensland. The article concludes by making recommendations for improving healthcare quality and safety in this area. Introduction: the Australian Public Health System’s Increasing Dependence on OTDs This article explores one of the most intriguing and hitherto largely unexplored aspects of healthcare quality and safety investigations in Australia: the role of a protagonist’s status as an overseas-trained doctor (“OTD”). It commences with an exploration of some of the regulatory problems associated with the increasing use of OTDs to provide basic health 74 services in some areas of Australia. -

Healthier Decision Making for Healthier Hospital on Queensland…

COVER SHEET This is the author-version of article published as: Casali, Gian Luca (2006) Towards Healthier Decision Making: A call for a multi criteria approach. In Cohen, Stephen, Eds. Proceedings 13th Conference Australian Association for Professional & Applied Ethics (AAPAE), University of New South Wales (Sydney, Australia). Copyright 2006 (please consult author) Accessed from http://eprints.qut.edu.au Towards Healthier Decision Making: A call for a multi criteria approach Keywords: Business Ethics, Decision Making, Organizational Culture, Hospitals Abstract Recently, the pages of the newspapers have been filled with many disturbing headlines about the health sector crisis, and especially professional staff working at the public hospitals. The scandal of Dr Patel at the Bundaberg Hospital and the unqualified Russian refugee who posed as a psychiatrist and treated more then 250 mental patients are only a few examples of a Health sector with significant problems. In order to cure the current situation of the Health sector, more is required than just changing a few senior managers as “scapegoats”. There is therefore a vital need for a more ethical approach to decision making at all levels of the organization. In this atmosphere of uncertainty and unhappiness in relation to the Health sector, decision makers in the health sector need a decision making tool that would assist them in making more ethical decisions. In order to meet that need a multi criteria framework for decision makers that combines a variety of ethical principles has been developed. This paper refers to that ethical multi criteria framework as “Healthier Decision”, and it incorporates ideologies derived from four schools of moral philosophies such as Egoism, Utilitarian, Virtue Ethics and Deontology.