Tony Cokes This Isn't Theory. This Is History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Song Artist 25 Or 6 to 4 Chicago 5 Years Time Noah and the Whale A

A B 1 Song Artist 2 25 or 6 to 4 Chicago 3 5 Years Time Noah and the Whale 4 A Horse with No Name America 5 Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus 6 Adelaide Old 97's 7 Adelaide 8 Africa Bamba Santana 9 Against the Wind Bob Seeger 10 Ain't to Proud to Beg The Temptations 11 All Along the W…. Dylan/ Hendrix 12 Back in Black ACDC 13 Bad Leroy Brown Jim Croce 14 Bad Moon Risin' CCR 15 Bad to the Bone George Thorogood 16 Bamboleo Gipsy Kings 17 Black Horse and… KT Tunstall 18 Born to be Wild Steelers Wheels 19 Brain Stew Green Day 20 Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison 21 Chasing Cars Snow Patrol 22 Cheesburger in Para… Jimmy Buffett 23 Clocks Coldplay 24 Close to You JLS 25 Close to You 26 Come as you Are Nirvana 27 Dead Flowers Rolling Stones 28 Down on the Corner CCR 29 Drift Away Dobie Gray 30 Duende Gipsy Kings 31 Dust in the Wind Kansas 32 El Condor Pasa Simon and Garfunkle 33 Every Breath You Take Sting 34 Evil Ways Santana 35 Fire Bruce Springsteen Pointer Sis.. 36 Fire and Rain James Taylor A B 37 Firework Katy Perry 38 For What it's Worth Buffalo Springfield 39 Forgiveness Collective Soul 40 Free Bird Lynyrd Skynyrd 41 Free Fallin Tom Petty 42 Give me One Reason Tracy Chapman 43 Gloria Van Morrison 44 Good Riddance Green Day 45 Have You Ever Seen… CCR 46 Heaven Los Lonely Boys 47 Hey Joe Hendrix 48 Hey Ya! Outcast 49 Honkytonk Woman Rolling Stones 50 Hotel California Eagles 51 Hotel California 52 Hotel California Eagles 53 Hotel California 54 I Won't Back Down Tom Petty 55 I'll Be Missing You Puff Daddy 56 Iko Iko Dr. -

London Sinfonietta

martedì 3 settembre 2002 ore 21 Teatro Regio London Sinfonietta HK Gruber, direttore Kurt Weill (1900-1950) Mahagonny, Songspiel Auf nach Mahagonny Alabama Song Wer in Mahagonny blieb Benares Song Gott in Mahagonny Aber dieses ganze Mahagonny Testi di Bertolt Brecht curati da David Drew Rievocazione della prima esecuzione avvenuta a Baden Baden nel 1927 con proiezione di bozzetti di Caspar Neher Coordinamento e libera ricostruzione delle proiezioni a cura di Gottfried Wagner JESSIE Linda Kitchen, soprano BESSIE Susan Bickley, mezzosoprano CHARLIE Ian Caley, tenore BILLY Christopher Gillett, tenore BOBBY Karl Daymond, baritono JIMMY Stephen Richardson, basso Canzoni da Happy End Testi originali in tedesco di Bertolt Brecht nella traduzione inglese di Michael Feingold; ordine di esecuzione di David Drew Prologue - Memories and Renovations Waltz - Bilbao Song Hellfire and Repentance Ballad of the Lily of Hell The Liquor Dealer’s Dream Brother, Give Yourself a Shove The Sailors’ Tango Youth and Experience In our Childhood Mandalay Song Surabaya Johnny Poverty and Riches March Ahead Lieutenant of the Lord Brother, give yourself a Shove (ripresa) Song of the Big Shot Hosannah Rockefeller Epilogue - Benedictions Don’t be Afraid In our Childhood (ripresa) Linda Kitchen, soprano Susan Bickley, mezzosoprano Karl Daymond, baritono Stephen Richardson, basso Ian Caley, Christopher Gillett, tenori Edward Beckett, flauto, ottavino Duncan Prescott, clarinetto David White, clarinetto, clarinetto basso Simon Haram*, sax contralto, clarinetto Christian Forshaw, sax tenore e basso, clarinetto Mark O'Keeffe, Bruce Nockles, trombe David Purser*, trombone Clio Gould*, Joan Atherton*, violini Steve Smith, chitarra, banjo Tracey Goldsmith, fisarmonica John Constable*, pianoforte, armonium Timothy Palmer, Joby Burgess, percussioni Ian Dearden, tecnico del suono * membri residenti Descritta da “The Independent” come «il campione pre-emi- nente della musica d’avanguardia…», la London Sinfonietta si è dedicata all’esecuzione ai massimi livelli della musica con- temporanea. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Piano • Vocal • Guitar • Folk Instruments • Electronic Keyboard • Instrumental • Drum ADDENDUM Table of Contents

MUsic Piano • Vocal • Guitar • Folk Instruments • Electronic Keyboard • Instrumental • Drum ADDENDUM table of contents Sheet Music ....................................................................................................... 3 Jazz Instruction ....................................................................................... 48 Fake Books........................................................................................................ 4 A New Tune a Day Series ......................................................................... 48 Personality Folios .............................................................................................. 5 Orchestra Musician’s CD-ROM Library .................................................... 50 Songwriter Collections ..................................................................................... 16 Music Minus One .................................................................................... 50 Mixed Folios .................................................................................................... 17 Strings..................................................................................................... 52 Best Ever Series ...................................................................................... 22 Violin Play-Along ..................................................................................... 52 Big Books of Music ................................................................................. 22 Woodwinds ............................................................................................ -

Songs by Artist 08/29/21

Songs by Artist 09/24/21 As Sung By Song Title Track # Alexander’s Ragtime Band DK−M02−244 All Of Me PM−XK−10−08 Aloha ’Oe SC−2419−04 Alphabet Song KV−354−96 Amazing Grace DK−M02−722 KV−354−80 America (My Country, ’Tis Of Thee) ASK−PAT−01 America The Beautiful ASK−PAT−02 Anchors Aweigh ASK−PAT−03 Angelitos Negros {Spanish} MM−6166−13 Au Clair De La Lune {French} KV−355−68 Auld Lang Syne SC−2430−07 LP−203−A−01 DK−M02−260 THMX−01−03 Auprès De Ma Blonde {French} KV−355−79 Autumn Leaves SBI−G208−41 Baby Face LP−203−B−07 Beer Barrel Polka (Roll Out The Barrel) DK−3070−13 MM−6189−07 Beyond The Sunset DK−77−16 Bill Bailey, Won’t You Please Come Home? DK−M02−240 CB−5039−3−13 B−I−N−G−O CB−DEMO−12 Caisson Song ASK−PAT−05 Clementine DK−M02−234 Come Rain Or Come Shine SAVP−37−06 Cotton Fields DK−2034−04 Cry Like A Baby LAS−06−B−06 Crying In The Rain LAS−06−B−09 Danny Boy DK−M02−704 DK−70−16 CB−5039−2−15 Day By Day DK−77−13 Deep In The Heart Of Texas DK−M02−245 Dixie DK−2034−05 ASK−PAT−06 Do Your Ears Hang Low PM−XK−04−07 Down By The Riverside DK−3070−11 Down In My Heart CB−5039−2−06 Down In The Valley CB−5039−2−01 For He’s A Jolly Good Fellow CB−5039−2−07 Frère Jacques {English−French} CB−E9−30−01 Girl From Ipanema PM−XK−10−04 God Save The Queen KV−355−72 Green Grass Grows PM−XK−04−06 − 1 − Songs by Artist 09/24/21 As Sung By Song Title Track # Greensleeves DK−M02−235 KV−355−67 Happy Birthday To You DK−M02−706 CB−5039−2−03 SAVP−01−19 Happy Days Are Here Again CB−5039−1−01 Hava Nagilah {Hebrew−English} MM−6110−06 He’s Got The Whole World In His Hands -

Name C:\ \ C:\ \4 NON BLONDES\ WHAT's up C:\ \883 MAX PEZZALI

Name C:\ \ C:\ \4 NON BLONDES\ WHAT'S UP C:\ \883 MAX PEZZALI\ 883 MIX AEROPLANO ANDRÀ TUTTO BENE BELLA VERA CHE GIORNO SARÀ CHIUDITI NEL CESSO CI SONO ANCH'IO COME DENTRO UN FILM COME DEVE ANDARE COME MAI CON DENTRO ME CON UN DECA CREDI CUMULI DIMMI PERCHE' DURI DA BATTERE E' VENERDI ECCOTI FAI COME TI PARE FAVOLA SEMPLICE FINALMENTE TU GLI ANNI GRAZIE MILLE HANNO UCCISO L'UOMO RAGNO HANNO UCCISO L'UOMO RAGNO IL MEGLIO DEVE ANCORA ARRIVARE IL MIO SECONDO TEMPO IL MONDO INSIEME A TE IN QUESTA CITTA' INNAMORARE TANTO IO CI SARÒ JOLLY BLUE LA DURA LEGGE DEL GOL LA LUNGA ESTATE CALDISSIMA LA MIA BANDA SUONA IL RAP LA RADIO A 1000 WATT LA REGINA DEL CELEBRITA' LA REGOLA DELL'AMICO LA STRADA LA VITA E' UN PARADISO DI BUGIE LASCIATI TOCCARE LE CANZONI ALLA RADIO LE LUCI DI NATALE LO STRANO PERCORSO L'ULTIMO BICCHIERE MAI UGUALI ME LA CAVERO' MEZZO PIENO O MEZZO VUOTO NELLA NOTTE NESSUN RIMPIANTO NIENT'ALTRO CHE NOI NOI NON MI ARRENDO NON PENSAVI NON TI PASSA PIÙ NORD SUD OVEST EST QUALCOSA DI NUOVO QUELLO CHE CAPITA RITORNERO' ROTTA PER CASA DI DIO SE TI MUOVI COSI' SE TORNERAI SE UNA REGOLA C'E' SEI FANTASTICA SEI UN MITO SEI UNO SFIGATO SEMBRO MATTO SENZA AVERTI QUÌ SIAMO AL CENTRO DEL MONDO SIAMO QUEL CHE SIAMO SOLITA ITALIA TENENDOMI TI SENTO VIVERE TIENI IL TEMPO TORNO SUBITO TUTTO CIO' CHE HO TUTTO CIÒ CHE HO UN GIORNO COSI UN GIORNO COSI' UNA CANZONE D'AMORE UNA LUNGA ESTATE CALDISSIMA UN'ESTATE CI SALVERA' UNO IN PIÙ UNO SFIGATO VIAGGIO AL CENTRO DEL MONDO WEEKEND WELCOME TO MIAMI YOU NEEDED ME C:\ \A HA\ ANALOGUE COSY PRISONS DREAM -

Joey Leone Songlist

Joey Leone’s Chop Shop Playlist (see note at bottom of playlist *) Classic Country Ring of Fire Folsom Prison Blues Walk the Line Working Man Blues Truck Driving man Six Days on the Road Guitars, Cadillacs, Lonesome me Eastbound and Down Poke Salad Annie Summertime Blues These Boots are Made for Walking Act Naturally Sit Here and Drink Boy Named Sue Rocky Top Sugarfoot Rag Hey Good Looking Cocaine Blues Gentle on My Mind Wichita Lineman Cheating Heart Southern Rock Sweet Home Alabama Simple Man Free Bird The Breeze One Way Out Midnight Rider Statesboro Blues Cripple Creek Take it Easy Peaceful Easy Feeling Classic Rock Sultans of Swing Money For Nothing La Grange Just Got Paid I’m Your Captain Born on The Bayou Proud Mary Bad Moon Rising Lodi Running Down A Dream LocoMotive Breath Roadhouse Blues LA Woman Love Me Two Times Back Door Man Old Man Rocking in the Free World Down By the River Jeepster Bang a Gong I Shot The Sheriff Secret Agent Man Stuck in the Middle Go Your Own Way Listen to the Music Behind Blue Eyes Pinball Wizard Mississippi Queen Jenny 8675309 Hard Rock Blitzkreig Bop I Wanna Be Sedated Breaking the Law You Got Another Thing Coming Anarchy in the UK War Pigs Paranoid Planet Caravan Fly Away Ace of Spades Day of The Eagle Smells Like Teen Spirit Come As You Are Fight For Your Right to Party ROLLING STONES jumping jack flash gimme shelter cant always get what u want let it bleed sympathy for the devil dead flowers wild horses angie 2000 light years from home no expectations love in vein satisfaction live with me honky tonk -

Hey Joe B, Ne Rêvons Pas !

Hey Joe B, ne rêvons pas ! « Hey Joe B / Cours pas comme çà / Dis, y’a pas le feu chez toi / Hey Joe B / viens pas dire bonjour / t’en mourras pas ! » (1) On y est presque ! Le twitter fou, Donald T, va quitter le bureau ovale. Il n’est pas pressé, loin de là, c’est prévu pour le 20 janvier. Il a encore le temps d’apposer ses graffitis sur les murs de la Maison Blanche. Il est capable de tout, c’est à ça qu’on les reconnaît « les C.. » disait Audiard, ils osent tout. Pour une fois, et pour cette fois seulement, on a envie de dire comme le petit Nicolas « casse-toi pov’ C.. ». Tout le monde devrait respirer. Une moitié des américains est contente, heureuse. L’autre moitié reste attachée au fou. Il ne va pas être facile pour Joe B de prendre les choses en main, de gouverner, et ce d’autant plus qu’il devra composer avec les sénateurs qui, majoritairement, ne sont pas de son bord. Donald T s’accroche, s’incruste ! « Moi, je pars à l’heure qui me plaît / J’ai même plus d’montre, / J’ai tout mon temps / C’qui m’attend chez moi, je le sais / De toute manière j’ai gagné / je fais ce qu’il m’plaît » Enfin, les Américains vont peut-être voir survivre leur « simili » sécu en modèle réduit mis en place par le sieur Obama. Pour eux, ces choses-là ne peuvent que s’améliorer, alors que pour la France, pas d’amélioration : la sécu est de plus en plus attaquée. -

(MAMA) - Elvis Presley 1954 a 30

2020 1. ROCK AROUND THE CLOCK - Bill Haley & Comets 1954 A 29. HAVE YOU EVER SEEN THE RAIN - CCR 1970 (intro #Fm) A 2. THAT’S ALL RIGHT (MAMA) - Elvis Presley 1954 A 30. IMAGINE - John Lennon 1971 C 3. MANNISH BOY - Muddy Waters 1955 A 31. WHISKY IN THE JAR - Thin Lizzy 1972 (Irish tradit.) (intro Am) G 4. ROLL OVER BEETHOVEN - Chuck Berry 1956 D 32. CAROLINE - Status Quo 1973 F 5. JAILHOUSE ROCK - Elvis Presley 1957 C 33. T.N.T - AC/DC 1975 D 6. JOHNNY B. GOODE - Chuck Berry 1958 A 34. HOTEL CALIFORNIA - The Eagles 1976 #Fm 7. RUN RUDOLPH RUN - Chuck Berry 1958 A 35. THE PASSENGER - Iggy Pop 1977 A 8. SUMMERTIME BLUES - orig. Eddie Cochran 1958 36. SPANISH GUITAR - Gary Moore 1979 Em - Brian Setzer (La Bamba OST) 1987 E 37. REDEMPTION SONG - Bob Marley 1980 9. APACHE - The Shadows 1960 Am 38. SHOULD I STAY OR SHOULD I GO – The Clash 1981 D 10. STAND BY ME - Ben E. King 1961 G 39. I LOVE ROCK’N’ROLL - Joan Jet 1982 orig. Arrows 1975 E 11. MISIRLOU - Dick Dale (from Pulp Fiction) 1962 E 40. REBEL YELL - Billy Idol 1983 Hm 12. WIPE OUT - The Surfaris 1962 C 41. MONEY FOR NOTHING - Dire Straits 1985 Gm 13. BLOWIN’ IN THE WIND – Bob Dylan 1962 D 42. FIRE - Bruce Springsteen 1986 (nastala okoli 1977) 14. RING OF FIRE - Johnny Cash 1963 A orig. Robert Gordon 1978 G 15. THE HOUSE OF THE RISING SUN - The Animals 1964 Am 43. WANTED DEAD OR ALIVE - Bon Jovi 1986 (intro Dm) D 16. -

Hey Joe – Jimi Hendrix Tempo: 80 Bpm (USE SWING Beat!) Tuning

Hey Joe – Jimi Hendrix Tempo: 80 bpm (USE SWING beat!) Tuning: standard Chords Used: see “all chords” file Note: This is taken from an abridged live version I watched from Hendrix playing the Billy Roberts version - the guy that actually wrote this song - so a few of the lyrics are a bit different. Strumming Pattern: D, DDU, DDD, DU Intro Riff: The entire progression is: C5 – G – D5 – A – E C5 G D5 A E ………Hey Joe………where you goin' with that gun in your hand C5 G D5 A E ………Hey Joe, I said where you goin' with that gun in your hand, oh C5 G D5 A E I'm goin' down to shoot my old lady, you know I caught her messin' 'round with another man Huh! and that ain't too cool…. C5 G D5 A E ……..Hey Joe, I heard you shot your woman down, you shot her down now C5 G D5 A E ……..Hey Joe, I heard you shot your ol’ lady down, you shot her down in the ground yeah! C5 G D5 A E Yes, I did, I shot her, you know I caught her messin' round messin' round town C5 G D5 A E Yes I did I shot her, you know I caught my old lady messin' 'round town And I gave her the gun, and I shot her! C5 – G – D5 – A - E C5 G D5 A E …..…Hey Joe, I said where you gonna run to now where you gonna run to? C5 G D5 A E …….Hey Joe, I said, where you gonna run to now where you gonna go? C5 G D5 A E Well I'm goin' way down south, way down to Mexico way..alright. -

Hey Joe (Jimi Hendrix)

Hey Joe (Jimi Hendrix) [Intro] [Guitar Solo/Bridge] Hey Joe Hey Joe, alright Where you going with that gun in your Shoot her one more time, baby hand? Hey Joe [Verse 4] I said where you going with that gun in your Hey Joe, said now hand? Where you going to run to now? Where you going to run to? [Verse 1] Hey Joe, I said I'm going down to shoot my old lady Where you going to run to now? You know, I caught her messing around Where you, where you going to go? with another man Well, dig it I'm going down to shoot my old lady You know, I caught her messing around [Verse 5] with another man I'm going way down south And that ain't too cool Way down to Mexico way Alright [Verse 2 ] I'm going way down south Hey Joe Way down where I can be free I heard you shot your woman down There's no one going to find me Shot her down, now Hey Joe [Verse 6] I heard you shot your old lady down There's no hangman going to You shot her down to the ground He ain't gonna put a rope around me You better believe it right now [Verse 3] I got to go now Yes I did, I shot her You know, I caught her messing around, messing around town [Outro] Yes I did, I shot her Hey Joe You know, I caught my old lady messing You better run on down around town Goodbye everybody, ow! And I gave her the gun Hey Joe, uh I shot her! Run on down 81 "Hey Joe" is an American popular song from the 1960s that has become a rock standard and has been performed in many musical styles by hundreds of different artists. -

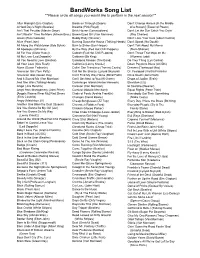

Bandworks Song List **Please Circle All Songs You Would Like to Perform in the Next Session**

BandWorks Song List **Please circle all songs you would like to perform in the next session** After Midnight (Eric Clapton) Break on Through (Doors) Don’t Change Horses [In the Middle A Hard Day’s Night (Beatles) Breathe (Pink Floyd) of a Stream] (Tower of Power) Ain’t That Peculiar (Marvin Gaye) Brick House (Commodores) Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Cryin’ Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More (Allman Bros.) Brown-Eyed Girl (Van Morrison) (Ray Charles) Alison (Elvis Costello) Buddy Holly (Weezer) Don’t Lose Your Cool (Albert Collins) Alive (Pearl Jam) Burning Down the House (Talking Heads) Don’t Speak (No Doubt) All Along the Watchtower (Bob Dylan) Burn to Shine (Ben Harper) Don’t Talk About My Mama All Apologies (Nirvana) By the Way (Red Hot Chili Peppers) (Mem Shanon) All For You (Sister Hazel) Cabron (Red Hot Chili Peppers) Don’t Throw That Mojo on Me All My Love (Led Zeppelin) Caldonia (Bb King) (Wynona Judd) All You Need Is Love (Beatles) Caledonia Mission (The Band) Do Your Thing (Lyn Collins) All Your Love (Otis Rush) California (Lenny Kravitz) Down Payment Blues (AC/DC) Alone (Susan Tedeschi) Callin’ San Francisco (Tommy Castro) Dreams (Fleetwood Mac) American Girl (Tom Petty) Call Me the Breeze (Lynyrd Skynyrd) Dr. Feelgood (Aretha Franklin) American Idiot (Green Day) Can’t Find My Way Home (Blind Faith) Drive South (John Hiatt) And It Stoned Me (Van Morrison) Can’t Get Next to You (Al Green) Drops of Jupiter (Train) And She Was (Talking Heads) Canteloupe Island (Herbie Hancock) Elevation (U2) Angel (Jimi Hendrix) Caravan (Van Morrison)