Protection on Nonenemy Interests in Enemy Corporations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Insignia VXR Supersport 22 Corsa, GTC, Insignia Technical Guide 28 Machines That Just Demand to Be Driven

2017 Models Edition 1 2 | VXR NEW LIMITS VXR RANGE Live the Change 4 Corsa VXR 6 This is extra-sensory stimulation. Cars with soul and power to make you GTC VXR 14 feel alive, electrified and inspired. A range of driver-focused, performance Insignia VXR SuperSport 22 Corsa, GTC, Insignia Technical Guide 28 machines that just demand to be driven. Corsa, GTC, Insignia Infotainment 34 New VXR8 GTS 36 New VXR8 Maloo LSA 42 New VXR8 Enhanced Driver Interface 44 New VXR8 Chassis Dynamics 46 Vauxhall OnStar 48 My Vauxhall 50 VXR Colours and Trims 52 This brochure covers Corsa VXR, GTC VXR, Insignia VXR SuperSport, New VXR8 GTS and New VXR8 Maloo LSA models only. Some of the models shown include options and accessories available at extra cost. And not all of the features described are available on every model. So for all current model or equipment details visit: www.vxr.co.uk The colours reproduced throughout this brochure may vary slightly from the actual paint colour. As a result, they should be used as a guide only. Your Vauxhall retailer has a comprehensive display of our paint samples. VXR LIVE THE CHANGE Advances in automotive technology have diluted the modern driving experience to the point where many of today’s ‘performance’ cars have become soulless and uncommunicative. You feel like you’re not actually driving. You feel like you’re being driven: you feel disconnected. VXR changes all that. VXR is here to reconnect the driver to the road – not with a wire, but with a heartbeat. -

Year in Review 2015 Facts & Figures Opel Mokka X

YEAR IN REVIEW 2015 FACTS & FIGURES OPEL MOKKA X More information about Opel: Weitere Informationen über Opel: opel.com opel.de For media: Für Journalisten: media.opel.com media.opel.de Social Media: https://www.facebook.com/Opel https://www.youtube.com/opel http://twitter.com/opel http://instagram.com/opelofficial https://plus.google.com/+Opel https://www.facebook.com/OpelDE https://www.youtube.com/opelde http://twitter.com/opelDE http://twitter.com/KT_Neumann/@ KT_Neumann http://www.opel-blog.com/ If you have any questions, please contact: Bei Fragen wenden Sie sich bitte an: Nico Schmidt +49 61 42 77 83 25 [email protected] Alexander Bazio +49 61 42 77 29 14 [email protected] Rainer Rohrbach +49 61 42 77 28 22 [email protected] This document was produced by Opel Corporate Communications, February 2016 Dieses Dokument wurde produziert von Opel Corporate Communications, Februar 2016 Layout | Gestaltung: www.designkultur-wiesbaden.de INDEX INHALT AT A GLANCE – 2015 5 ÜBERBLICK – 2015 5 CHAPTER I: COMPANY KAPITEL I: DAS UNTERNEHMEN Management Board 7 Geschäftsführung 7 Heritage 8 Geschichte 10 Innovations 12 Innovationen 15 Awards 17 Auszeichnungen 18 Opel Locations in Europe 20 Opel-Standorte in Europa 20 CHAPTER II: VEHICLES & TECHNOLOGIES KAPITEL II: FAHRZEUGE & TECHNOLOGIEN Vehicles 23 Fahrzeuge 23 Technologies 34 Technologien 34 CHAPTER III: PRODUCTION KAPITEL III: PRODUKTION Production by Country and Plant 36 Produktion nach Ländern und Werken 36 Vehicle Production by Model 37 Fahrzeugproduktion nach Modellen -

Adam Opel 87

Adam Opel 87 Abbn.: oben: Denkmal von Adam Opel vor dem Hauptportal des Opelwerks in Rüsselsheim unten: Opel Patentmotorwagen „System Lutzmann“ 1311 Mit der Erfindung des Automobils begann auch eine neue Ära in der Geschichte der Straße VIA REGIA. Im Jahre 1900 wurden weltweit insgesamt 4.192 Automobile gebaut: mit Dampf, Elektrizität oder Benzin angetrie- ben. Die technische Zukunft der neuen Fahrzeuge war damals durchaus noch ungewiss. Eine der Produkti- onsstätten, die sich alsbald zu einer der größten Autohersteller in Europa entwickeln sollte, war die Adam Opel AG in der VIA REGIA-Stadt Rüsselsheim. Adam Opel wurde als ältester Sohn des Schlossermeisters Philipp Wilhelm Opel geboren. Er erlernte in der Werkstatt des Vaters den Beruf eines Schlossers. Die Wanderjahre führten ihn ab 1857 über Belgien und England nach Paris, wo er in zwei Nähmaschinenfabriken arbeitete. Wieder in seiner Heimatstadt, gründete Opel 1862 seine eigene Nähmaschinenmanufaktur. Im Jahre 1884 stellte sein Betrieb bereits 18.000 Nähma- schinen pro Jahr her. 1886 begann Opel auch mit der Herstellung von Fahrrädern. Die Firma entwickelte sich schnell zum größten Fahrradhersteller in Deutschland. Aber erst seine Söhne begannen 1898, drei Jahre nach dem Tod des Firmengründers mit der Produktion von Autos. Sie kauften am 21. Januar 1899 die Anhaltische Motorwagenfabrik des Dessauer Hofschlossermeisters, Automobilpioniers und Konstrukteurs Friedrich Lutz- mann, machten ihn zum Direktor und begannen mit dem Bau der Opel Patentmotorwagen „System Lutzmann“ in Rüsselsheim. Kurz vor seinem Tod soll Adam Opel beim Anblick eines Automobils gesagt haben: „Aus diesem Stinkkasten wird nie mehr werden als ein Spielzeug für Millionäre, die nicht wissen, wie sie ihr Geld wegwerfen sollen!“ Aus dem ältesten Werksteil, der bis heute „Kuhstall“ genannt wird (in Anspielung auf die Bedingungen, unter denen die Produktion einst begann)‚ wurde das größte hessische Unternehmen der Automobilherstellung. -

And the All New

ADAM2016 Models Edition 2 AND THE ALL NEW www.vauxhalladam.co.uk VX_ADAM_23864 VX_ADAM_18693 VX_ADAM_18984 VX_ADAM_22586 VX_ADAM_19009 VX_ADAM_19007 VX_ADAM_18995 VX_ADAM_18988 You. That’s who it’s all about. It’s why we made ADAM – to give you freedom to express your originality, starting with a daring attitude and smart colours. Then you have the pick of the ADAM JAM, VX_ADAM_19003 GLAM, and SLAM models, not forgetting the sporty ADAM S with its eager 150PS 1.4 Turbo engine. Or maybe you fancy a rugged twist on urban chic? VX_ADAM_19001 Then check out the ADAM ROCKS and ROCKS AIR models. Just like you, every ADAM’s an individual. Each one’s got its own personality, looks and superpowers. So have a flick through, find your favourite ADAM, then simply add you. We guarantee good times ahead. VX_ADAM_18983 Meet ADAM online at vauxhalladam.co.uk VX_ADAM_23866 VX_ADAM_19000 VX_ADAM_18998 VX_ADAM_19010 VX_ADAM_19002 VX_ADAM_18989 VX_ADAM_18985 VX_ADAM_19008 VX_ADAM_19005 VX_ADAM_18981 VX_ADAM_22586 VX_ADAM_23865 VX_ADAM_18987 VX_ADAM_18996 CONTENTS ADAM JAM 8 ADAM GLAM 10 ADAM SLAM 12 ADAM S 14 VX_ADAM_18997 ADAM ENERGISED 18 ADAM ROCKS 2 VX_ADAM_18999 0 VX_ADAM_19003 ENGINES 22 BODY & ROOF COLOURS 24 OPTIONS 26 VX_ADAM_18990 INFOTAINMENT 28 ONSTAR 30 VX_ADAM_18986 MY VAUXHALL 32 ACCESSORIES 34 VX_ADAM_18993 VX_ADAM_23866 VX_ADAM_18994 VX_ADAM_19006 VX_ADAM_18992 VX_ADAM_21196 VX_ADAM_19010 DON’T FOLLOW TRENDS. SET THEM. VX_ADAM_18984 VX_ADAM_23868 DON’T FOLLOW TRENDS. VX_ADAM_18985 SET THEM. ADAM JAM illustrated features Urban Pack and Pump up the Blue two-coat pearlescent paint, optional at extra cost. ADAM GLAM illustrated features Style Pack and Purple Fiction two-coat pearlescent paint, optional at extra cost. ADAM SLAM illustrated features Extreme Carbon Pack, VXR Styling Pack and James Blonde brilliant paint, all optional at extra cost. -

Opel Astra Station Wagon: Technical Data Overview

Opel Astra Station Wagon: Technical Data Overview Astra Station Wagon Gasoline engines 1.4 1.6 1.8 2.0 Turbo 2.0 Turbo TWINPORT TWINPORT ECOTEC ECOTEC ECOTEC ECOTEC ECOTEC Emissions standard compliance Euro 4 Euro 4 Euro 4 Euro 4 Euro 4 Fuel super unleaded super unleaded super unleaded super unleaded super unleaded Number of cylinders 4 4 4 4 4 Displacement in cm³ 1364 1598 1796 1998 1998 Max. output in kW (hp) 66 (90) 77 (105) 103 (140) 125 (170) 147 (200) at rpm 5600 6000 6300 5200 5400 Max. torque in Nm 125 150 1751) 250 262 at rpm 4000 3900 3800 1950 – 4000 4200 Transmission 5-speed manual z z z – – 6-speed manual – – – z z 5-speed Easytronic – O – – – 4-speed automatic – – O – – Trailer load in kg Unbraked 640 650 660 710 710 Braked (10% gradient) 1100 1300 14002) – – Braked (12% gradient) 900 1100 1300 14003) 14003) 1) 170 Nm in combination with automatic transmissions 2) 1500 kg for trailers with low aerodynamic drag such as horse and boat trailers, as well as transport trailers with up to 1.40 m total height, maximum 10% gradient 3) 1600 kg for trailers with low aerodynamic drag such as horse and boat trailers, as well as transport trailers with up to 1.40 m total height, maximum 12% gradient z = Standard, { = Optional, – = Not available Adam Opel GmbH http://media.opel.com General Motors Corporation D-65423 Rüsselsheim - 2 - Astra Station Wagon Diesel engines 1.3 CDTI 1.9 CDTI 1.9 CDTI 1.9 CDTI ECOTEC ECOTEC ECOTEC ECOTEC Emissions standard compliance Euro 4 Euro 4 Euro 4 Euro 4 Fuel diesel diesel diesel diesel Number of cylinders 4 4 4 4 Displacement in cm³ 1248 1910 1910 1910 Max. -

Opel History 1960-1969

Opel History 1960-1969 1960 The Opel Rekord P2 arrives. About 755,000 units are to be built in total. The Opel Rekord P2, 1960– The Opel Rekord P2, 1960– The Opel Rekord P2 station wagon, 1963. 1963. 1960–1963. 1961 A sporty coupe is launched, rounding off the model line. The Opel Rekord P2 Coupe, 1960– The Opel Rekord P2 Coupe, 1960– 1963. 1963. 1962 Opel celebrates its one-hundredth anniversary. A plant is inaugurated in Bochum for the production of the new Opel Kadett. A procession of cars marks A gala event on August 14, The Opel Kadett A, 1962– The Opel Kadett A Coupe, the 100-year jubilee of 1962, is held to celebrate the 1965. 1963–1965. Adam Opel AG, 1962. 100-year jubilee of Adam Opel AG. German Minister of Economic Affairs Prof. Dr. Ludwig Erhard addresses the assembly. The new Opel plant in Final assembly (wedding) of an Opel Advertisement for the Opel Kadett Bochum, 1962. Kadett A in the Bochum plant, 1963. A, 1963–1965. 1963Opel Rekord A is presented. The Opel Rekord A Coupe, Advertisement for the Opel The Opel Rekord A All Opel Rekord A and 1963–1965. Rekord A, 1963. undergoes a final check in Kadett A models built in the Rüsselsheim plant, 1963. 1963–64 sport this variant of the Blitz “bow and stern.” 1964Opel unveils three new luxury models: Kapitän, Admiral and Diplomat. These prestigious six- and eight-cylinder flagships capture the spirit of the times. All three are well received and become immediate market successes. The “big three” from Opel. -

Owners Manual

OPEL Corsa Owner’s Manual Back to overview Back to overview OPEL Corsa Operation, Safety, Maintenance Back to overview Data specific to your vehicle Please enter your vehicle’s data here so that it is readily accessible. Please refer to the sections "Servicing and maintenance" and "Technical data" and the identification plate. Fuel Designation Engine oil Grade Viscosity Tyre pressure Tyre size Front Rear Summer tyres Winter tyres Weights Gross vehicle weight rating – EC kerb weight =Loading Back to overview Introduction z The table of contents at the beginning of 3 signifies equipment not fitted to all Your vehicle is an intelligent combination the owner’s manual and within the vehicles (model variants, engine options, of forward-looking technology, impressive individual chapters will show you where models specific to one country, optional safety, environmental friendliness and everything is. equipment, Genuine Opel Parts and economy. z Its index will help you find what you Accessories). It now lies with you to drive your vehicle want. Page references are indicated with 3 . 3 safely and to see it performs perfectly. This z Yellow arrows in the illustrations serve as means "see page". Owner’s Manual provides you with all the points of reference or indicate some 9 Danger, 9 Warning, Caution necessary information to that end. action to be performed. Make sure your passengers are aware of z Black arrows in the illustrations indicate 9 Danger the possible risk of accident and injury a reaction or a second action to be which may result from improper use of the performed. Text marked 9 Danger provides vehicle. -

Miete Und Carsharing

DAS FACHMAGAZIN FÜR INNOVATIVES FUHRPARK- UND MOBILITÄTSMANAGEMENT G 59522 • 13. Jahrgang • EUR 4,– 1/2014 FEBRUAR/MÄRZ www.flotte.de Miete und Carsharing REDAKTIONSBEIRAT: Fachgespräche FLOTTEN-STRATEGIEN: Mercedes-Benz, Fiat KOSTENVERGLEICH: Kleinwagen RECHT: Falschparker auf dem Firmenparkplatz Mal mehr – mal weniger. Die flexible Systemlösung für schwankendem Mobilitätsbedarf. Euromobil Fleet-Service ist die effiziente Mietwagenlösung für Unternehmen mit großem Fuhrparkbedarf – der erfolgreiche Weg zur Prozessoptimierung und Aufwandminimierung in allen Bereichen des Fuhrpark-Managements in Ihrem Unternehmen: • Werkstatt-/Unfallersatzwagen, Mietwagen PKW/Nutzfahrzeuge, für Kurz- oder Langzeitmiete • Deutschlandweit einheitliche Preise bei Werkstattaufenthalt und Zusatzbedarf • Attraktive Konditionen mit umfangreichen Inklusivleistungen • Alles aus einer Hand: Beschaffung, Reparatur, Service und Miete – bei Ihrem Autohaus vor Ort • Kurze und einheitliche Beschaffungswege durch dichtes Stationsnetz • Hochwertiger, junger Mietfahrzeugpool, perfekt auf Ihren Bedarf abgestimmt Euromobil – Marken-Autovermietung für Volkswagen, Volkswagen Nutzfahrzeuge, Audi, SEAT, SˇKODA. euromobil.de EDITORIAL Ralph Wuttke, Chefredakteur Flottenmanagement Das Autojahr 2014 Passend zum wirtschaftlichen Aufschwung in Auch 2014 wird der Schwerpunkt wieder auf Hybride. Hier kann sich der Chef auf den Merce- Deutschland zündet die Automobilbranche verbrauchsreduzierten konventionellen Moto- des S 500 Plug-in-Hybrid freuen, der „normale“ 2014 ein Modellfeuerwerk. -

Acronimos Automotriz

ACRONIMOS AUTOMOTRIZ 0LEV 1AX 1BBL 1BC 1DOF 1HP 1MR 1OHC 1SR 1STR 1TT 1WD 1ZYL 12HOS 2AT 2AV 2AX 2BBL 2BC 2CAM 2CE 2CEO 2CO 2CT 2CV 2CVC 2CW 2DFB 2DH 2DOF 2DP 2DR 2DS 2DV 2DW 2F2F 2GR 2K1 2LH 2LR 2MH 2MHEV 2NH 2OHC 2OHV 2RA 2RM 2RV 2SE 2SF 2SLB 2SO 2SPD 2SR 2SRB 2STR 2TBO 2TP 2TT 2VPC 2WB 2WD 2WLTL 2WS 2WTL 2WV 2ZYL 24HLM 24HN 24HOD 24HRS 3AV 3AX 3BL 3CC 3CE 3CV 3DCC 3DD 3DHB 3DOF 3DR 3DS 3DV 3DW 3GR 3GT 3LH 3LR 3MA 3PB 3PH 3PSB 3PT 3SK 3ST 3STR 3TBO 3VPC 3WC 3WCC 3WD 3WEV 3WH 3WP 3WS 3WT 3WV 3ZYL 4ABS 4ADT 4AT 4AV 4AX 4BBL 4CE 4CL 4CLT 4CV 4DC 4DH 4DR 4DS 4DSC 4DV 4DW 4EAT 4ECT 4ETC 4ETS 4EW 4FV 4GA 4GR 4HLC 4LF 4LH 4LLC 4LR 4LS 4MT 4RA 4RD 4RM 4RT 4SE 4SLB 4SPD 4SRB 4SS 4ST 4STR 4TB 4VPC 4WA 4WABS 4WAL 4WAS 4WB 4WC 4WD 4WDA 4WDB 4WDC 4WDO 4WDR 4WIS 4WOTY 4WS 4WV 4WW 4X2 4X4 4ZYL 5AT 5DHB 5DR 5DS 5DSB 5DV 5DW 5GA 5GR 5MAN 5MT 5SS 5ST 5STR 5VPC 5WC 5WD 5WH 5ZYL 6AT 6CE 6CL 6CM 6DOF 6DR 6GA 6HSP 6MAN 6MT 6RDS 6SS 6ST 6STR 6WD 6WH 6WV 6X6 6ZYL 7SS 7STR 8CL 8CLT 8CM 8CTF 8WD 8X8 8ZYL 9STR A&E A&F A&J A1GP A4K A4WD A5K A7C AAA AAAA AAAFTS AAAM AAAS AAB AABC AABS AAC AACA AACC AACET AACF AACN AAD AADA AADF AADT AADTT AAE AAF AAFEA AAFLS AAFRSR AAG AAGT AAHF AAI AAIA AAITF AAIW AAK AAL AALA AALM AAM AAMA AAMVA AAN AAOL AAP AAPAC AAPC AAPEC AAPEX AAPS AAPTS AAR AARA AARDA AARN AARS AAS AASA AASHTO AASP AASRV AAT AATA AATC AAV AAV8 AAW AAWDC AAWF AAWT AAZ ABA ABAG ABAN ABARS ABB ABC ABCA ABCV ABD ABDC ABE ABEIVA ABFD ABG ABH ABHP ABI ABIAUTO ABK ABL ABLS ABM ABN ABO ABOT ABP ABPV ABR ABRAVE ABRN ABRS ABS ABSA ABSBSC ABSL ABSS ABSSL ABSV ABT ABTT -

Opel Insignia

OPEL INSIGNIA SENTIR ES LO QUE IMPORTA. Conducir el Opel Insignia es conducir un coche de clase superior. La innovación es lo que distingue a un líder como el Opel Insignia. Sus Sistemas Multimedia IntelliLink CONTENIDO personalizables dan continuidad a tu mundo digital, asegurándote una experiencia de alta calidad desde que inicias la marcha. Y esto sólo es el principio. El Insignia te traslada a un nuevo territorio gracias a sus sofisticados sistemas de asistencia al conductor, un lujoso interior, una refinada conducción y toda la eficacia de la ingeniería alemana Opel. Más allá de las palabras, te invitamos a descubrir el Insignia. OPEL INSIGNIA 04 Insignia 20 Modelos 26 Confort y Bienestar 28 Faros Adaptativos Inteligentes AFL Plus® 30 Sistemas de Asistencia 32 Protección de los Ocupantes 34 Conectividad 38 OnStar® y myOpel 42 Accesorios 44 Packs OPC 46 Motores y Transmisiones 48 Llantas y Neumáticos 50 Tapicerías y Acabado Interior 54 Colores Exteriores 56 Servicio y Garantía Opel 58 Innovaciones Opel El contenido de este catálogo está vigente en el momento de su impresión (02/2017). Queda reservado el derecho a modificar en cualquier momento las especificaciones y equipamientos mostrados. Por favor, consulte a su Concesionario Opel para conocer la información más actual. CREADO PARA DESAFIAR AL FUTURO. El diseño del Insignia es toda una declaración de estilo. Además puedes elegir entre tres tipos de carrocería: el estilizado 5 Puertas, el amplio y polivalente Sports Tourer o el sorprendente Country Tourer. Todos con la inconfundible clase Insignia. UN ICONO EN INNOVACIÓN. El Opel Insignia es un símbolo en su categoría. -

Technical Department - 12/01/2018

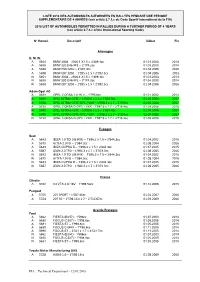

LISTE 2018 DES AUTOMOBILES AUTORISEES EN RALLYES PENDANT UNE PERIODE SUPPLEMENTAIRE DE 4 ANNEES (voir article 2.7.1.c du Code Sportif International de la FIA) 2018 LIST OF AUTOMOBILES PERMITTED IN RALLIES DURING A FURTHER PERIOD OF 4 YEARS (see article 2.7.1.c of the International Sporting Code) N° Homol. Descriptif Début Fin Allemagne B. M. W. A 5654 BMW 330d – 2926.1 X1.5 = 4'389.1cc 01.01.2003 2014 A 5658 BMW 320 E46/4FL – 2'174.2cc 01.04.2003 2014 A 5696 BMW E90 320si – 1'997.4cc 01.04.2006 2016 A 5698 BMW E87 120d – 1'995 x 1.5 = 2'992.5cc 01.04.2006 2016 N 5654 BMW 330d – 2926.1 X1.5 = 4'389.1cc 01.01.2003 2014 N 5658 BMW 320 E46/4FL – 2'174.2cc 01.04.2003 2014 N 5698 BMW E87 120d – 1'995 x 1.5 = 2'992.5cc 01.04.2006 2016 Adam Opel AG A 5638 OPEL CORSA 1.8 16 V – 1'795.6cc 01.01.2002 2014 A 5699 OPEL ASTRA H GTC – 1'909.6 x 1.5 = 2'864.4cc 01.04.2006 2017 A 5700 OPEL ASTRA H GTC‐OPC / VXR – 1'998.2 x 1.7 = 3'397cc 01.04.2006 2017 A 5720 OPEL CORSA D OPC / VXR - 1'597.9 x 1.7 = 2'716.4cc 01.09.2008 2015 N 5699 OPEL ASTRA H GTC – 1'909.6 x 1.5 = 2'864.4cc 01.04.2006 2017 N 5700 OPEL ASTRA H GTC‐OPC / VXR – 1'998.2 x 1.7 = 3'397cc 01.04.2006 2017 N 5720 OPEL CORSA D OPC / VXR - 1'597.9 x 1.7 = 2'716.4cc 01.09.2008 2015 Espagne Seat A 5643 IBIZA 1.9 TDI (96 KW) – 1'896.2 x 1.5 = 2'844.3cc 01.04.2002 2015 A 5675 ALTEA 2.0 FSI – 1'984.3cc 01.08.2004 2016 A 5683 IBIZA CUPRA D – 1'896.2 x 1.5 = 2'844.3cc 01.07.2005 2015 A 5687 LEON 2.0 TFSI – 1'984.3 x 1.7 = 3'373.3cc 01.08.2005 2016 N 5643 IBIZA 1.9 TDI (96 KW) – 1'896.2 x 1.5 = 2'844.3cc -

Liste Des Vehicules / N° Homologation Liste of Vehicles / Homologation Number

LISTE DES VEHICULES / N° HOMOLOGATION LISTE OF VEHICLES / HOMOLOGATION NUMBER N° Homol Pays Date Constructeur Description Fin MOT -01/2011 F 01.01.2011 Citroën MOTEUR CR 16 TI MOT -02/2011 F 01.01.2011 RML Group MOTEUR P203 MOT -03/2011 F 01.01.2011 Ford Motor Company MOTEUR EcoBoost GTDI MOT -01/2013 D 01.01.2013 Volkswagen POLO S2000 MOT 02/2013 RU 01.01.2013 Lada MOTEUR LADA GRANTA 1.6T MOT 03/2013 J 01.01.2013 Honda MOTEUR HR-412E MOT -04/2013 D 01.01.2013 Hyundai Motor Compagny I20 R 1.6 T-GDI A 5614 J 01.04.2000 Fuji Heavy Ind. Ltd SUB. PLEO SEDAN-RA – 658 x 1.7 = 1'118.5cc 2013 A 5625 I 01.03.2001 Alfa Romeo 147 T.SPARK 2.0 16V – 1'969.47cc 2015 A 5627 F 01.03.2001 Peugeot 206 XS – 1'587.46cc 2013 A 5633 CZ 01.09.2001 Skoda FABIA 1.4 – 1'397.2cc 2014 A 5634 CZ 01.10.2001 Skoda FABIA 1.9 TDI – 1'896.2 x 1.5 = 2'844.3cc 2014 A 5635 CZ 01.10.2001 Skoda FABIA 1.4 16V – 1'389.9cc 2014 A 5638 D 01.01.2002 Adam Opel AG OPEL CORSA 1.8 16 V – 1'795.6cc 2014 A 5643 E 01.04.2002 Seat IBIZA 1.9 TDI (96 KW) – 1'896.2 x 1.5 = 2'844.3cc 2015 A 5646 J 01.04.2002 Honda CIVIC TYPE R (EP3) – 1'998.2cc 2014 A 5652 J 01.01.2003 Fuji Heavy Ind.