Pulling Punches: Realism’S Requisite Restraint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

After the 'German Civil War' of 1866: Building The

Decades of Reconstruction Postwar Societies, State-Building, and International Relations from the Seven Years’ War to the Cold War Edited by UTE PLANERT University of Cologne JAMES RETALLACK University of Toronto GERMAN HISTORICAL INSITUTE Washington, D.C. and Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Toronto, on 23 May 2020 at 14:03:03, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316694091 University Printing House, Cambridge cb2 8bs, United Kingdom Cambridge University Press is part of the University of Cambridge. It furthers the University’s mission by disseminating knowledge in the pursuit of education, learning and research at the highest international levels of excellence. www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9781107165748 © Cambridge University Press 2017 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2017 Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Inc. A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library isbn 978-1-107-16574-8 Hardback isbn 978-1-316-61708-3 Paperback Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Toronto, on 23 May 2020 at 14:03:03, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. -

Wolfgang Roth / Spuren Jüdischen Lebens in Schaafheim Ab 1700 1

Wolfgang Roth / Spuren jüdischen Lebens in Schaafheim ab 1700 1 Wolfgang Roth Spuren von mehr als 250 Jahren jüdischen Lebens in der Gemeinde Schaafheim Schaafheim 2007 Wolfgang Roth / Spuren jüdischen Lebens in Schaafheim ab 1700 2 1. Erste Spuren vor 1750 1517 Gers (ten) musste in den Almosenkasten eine Strafe von 1 Gulden entrichten, weil er am Sonntag in Schaafheim seinen Pullkasten entleerte. (Kirchenbuch Ev Gemeinde Schaafheim + mündlich Hans Dörr) 1566 Dem Jud Nathan wurden in Schaafheim die Sparren vom Haus gestohlen. Weil er den Dieb nicht anzeigen wollte, wurde er wegen Vortäuschung eines Diebstahls verurteilt. (Kirchenbuch Ev Gemeinde Schaafheim + mündlich Hans Dörr) 1600 Die Juden Aaron und Salomon verlezten in Schaafheim bei einer Schlägerei durch Schläge auf den Kopf ein Mann schwer. Sie mussten als Sühne 100 spanische Reichstaler bezahlen! (Kirchenbuch Ev Gemeinde Schaafheim + mündlich Hans Dörr) Der Jud Salman (Salomon) musste in Schaafheim einen Hauszins bezahlen. (mündlich Hans Dörr) 1602 Der Hanauaer Graf veranlasste im Jahr 1602, dass alle Juden in Schaafheim ab Johannis, dem Täufer (Johannis-Tag am 24. Juni) den Ort Schaafheim verlassen mussten. (mündlich Hans Dörr) 1656 Laut Amtsprotokoll des Gerichts Schaafheim bezichtigte Itzig, der Jud den Schneider Cassian Wetzler ihn geschlagen und beschimpft hätte, obwohl er in die „Freiheit“ zu Schafheym geflüchtet war. Sie beschimpften sich im Gasthaus gegenseitig, wo der Schneider Cassian ein Messer zog. (mündlich Hans Dörr + Schaafheim Gerichts-Protokoll vom 30. Mai 1656) 1679 Am 6. Juni 1679 entschied die verwitwete Gräfin Anna Magdalena von Hanau- Lichtenberg über eine Supplik (Bittschrift) des Juden Jonas von Babenhausen vom 23. April 1679. Er war durch das Kriegswesen von Schaafheim nach Babenhausen verzogen. -

Introduction Prussia: War, Theory and Moltke

NOTES INTRODUCTION PRUSSIA: WAR, THEORY AND MOLTKE 001. From Stephen J. Gould, Leonardo’s Mountain of Clams and the Diet of Worms (New York, 1998), p. 393. Gould argues that post-modernist critique should give us a healthy scepticism towards the ‘complex and socially embedded reasons behind the original formulations of our established cat- egories’. Surely this applies to the Prussian military before 1914. 002. Gerhard Weinberg, Germany, Hitler and World War II: Essays in Modern Germany and World History (Cambridge, 1995), p. 287. 003. Although the image of nineteenth-century Germany had begun to shift a bit before August 1914, the sea change took place thereafter and since 1945 has been fairly uniformly grey, at least in the English cultural world. Fifty years past World War II has not erased the negative image of the ‘Hun’, German national character and Germany prior to August 1914. Peter E. Firchow, The Death of the German Cousin: Variations on a Literary Stereotype: 1890–1920 (Lewisburg, 1986), passim. 004. These are the three great historiographical controversies which have erupted since the end of World War II. Each one paints nineteenth-century Germany in dark, twentieth-century colours. The first and third confront the Prussian–German Army directly, describing it in militaristic terms. All three describe various attempts to attach the Third Reich, and especially the Holocaust, to German history before 1933, and especially before 1914. The Fischer controversy was touched off by the publication of Fritz Fischer’s book, Griff nach der Weltmacht (Düsseldorf, 1961), translated as Germany’s Aims in the First World War (New York, 1967), in which he argued that Nazi foreign policy was a continuation of German foreign policy in 1914–18. -

Charles University Faculty of Science Rndr. Daniel Reeves

Charles University Faculty of Science Study program: Social Geography and Regional Development Field of study: Social Geography and Regional Development RNDr. Daniel Reeves Territorial Identities and Religion in Czechia and Central Europe Územní identity a náboženství v Česku a střední Evropě Dissertation Doctoral thesis Prague 201 Advisor: RNDr. Tomáš Havlíček, Ph.D. 8 ii Prohlášení: Prohlašuji, že jsem závěrečnou práci zpracoval samostatně a že jsem uvedl všechny použité informační zdroje a literature. Tato práce ani její podstatná část nebyla předložena k získání jiného nebo stejného akademického titulu. Woods Cross, Utah, USA, . 201 30 4 8 RNDr. Daniel Reeves iii Abstract: Territorial identities are a mosaic of many different cultural elements, from which religion is just one subset. This dissertation explores elements of religion as they are expressed within territorial identities at varying scale levels in Czechia and several neighboring countries. The use of a religiously themed postage stamp or a Christian toponym, the inclusion of a religious site in a hand drawn map of one’s hometown or one’s position regarding the return of disputed properties to the churches they were taken from years ago, each of these can be an expression of territorial identity. Whether actively practiced or passively acknowledged, religion is bound up in our sense of place. The four separate studies that make up the body of this dissertation present religion’s case as an integral ingredient within the territorial identities of Central Europe. In terms of spatial differences, Slovakia and Poland are more likely, as compared to Czechia, to recognize and include elements of religion in their territorial identities. -

Question Paper 8 Pages

Cambridge International Examinations Cambridge International Advanced Subsidiary Level HISTORY 9389/12 Paper 1 Document Question May/June 2014 1 hour Additional Materials: Answer Booklet/Paper *9010708264* READ THESE INSTRUCTIONS FIRST If you have been given an Answer Booklet, follow the instructions on the front cover of the Booklet. Write your Centre number, candidate number and name on all the work you hand in. Write in dark blue or black pen. Do not use staples, paper clips, glue or correction fluid. DO NOT WRITE IN ANY BARCODES. This paper contains three sections: Section A: European Option Section B: American Option Section C: International Option Answer both parts of the question from one section only. At the end of the examination, fasten all your work securely together. The marks are given in brackets [ ] at the end of each part question. This document consists of 7 printed pages and 1 blank page. DC (NH/SLM) 84011/3 © UCLES 2014 [Turn over 2 Section A: European Option Liberalism and Nationalism in Italy and Germany, 1848–1871 Bismarck’s attitude to Austria 1 Read the sources and then answer both parts of the question. Source A Since Napoleon was defeated in 1815, Germany has clearly been too small for both Prussia and Austria. As long as an honourable arrangement about the influence of each country cannot be agreed and carried out, we will be rivals in the same disputed land. Austria will remain the only state to whom we can permanently lose or from whom we can permanently gain. For a thousand years, the balance between them has been adjusted by war. -

The Kingdom of Wurttenmerg and the Making of Germany, 1815-1871

Te Kingdom of Württemberg and the Making of Germany, 1815-1871. Bodie Alexander Ashton School of History and Politics Discipline of History Te University of Adelaide Submitted for the postgraduate qualification of Doctor of Philosophy (History) May 2014 For Kevin and Ric; and for June, Malcolm and Kristian. Contents Abstract vii Acknowledgements ix List of Abbreviations xi Notes xiii Introduction 15 Chapter 1 35 States and Nation in the Late Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Century Chapter 2 67 Stuttgart and Vienna before 1848 Chapter 3 93 Te Kingdom of Württemberg and Early Kleindeutschland Chapter 4 123 Independence and South German Particularism, 1815-1848 Chapter 5 159 Te Years of Prophecy and Change, 1848-1849 Chapter 6 181 Counterrevolution, Reaction and Reappraisals, 1850-1859 Chapter 7 207 Six Years of Autumn: 1860-1866 Chapter 8 251 Te Unification of Germany, 1866-1871 Conclusion 295 Bibliography 305 ABSTRACT _ THE TRADITIONAL DISCOURSE of the German unification maintains that it was the German great powers - Austria and Prussia - that controlled German destiny, yet for much of this period Germany was divided into some thirty-eight states, each of which possessed their own institutions and traditions. In explaining the formation of Germany, the orthodox view holds that these so-called Mittel- and Kleinstaaten existed largely at the whim of either Vienna or Berlin, and their policies, in turn, were dictated or shaped by these two power centres. According to this reading of German history, a bipolar sociopolitical structure existed, whereby the Mittelstaaten would declare their allegiances to either the Habsburg or Hohenzollern crowns. Te present work rejects this model of German history, through the use of the case study of the southwestern Kingdom of Württemberg. -

1 Harold W. Rood W.M. Keck Professor of International Strategic

1 Harold W. Rood W.M. Keck Professor of International Strategic Studies, Emeritus Claremont McKenna College December 2009 Commentary on Books and Other Works Useful in the Study of International Relations The 20th Century is an era worth study for an understanding of international politics because of the great conflict amongst nations as well as those within nations. But that century was hardly different from those that preceded it and is hardly likely to be different from those that follow it . For politics is at the heart of how groups of human beings arrange themselves or are arranged to achieve some order and predictability in the course of human endeavors, whether they are fortunate enough to govern themselves or must submit to government by a special designate few . Those who, by right, govern themselves, do so most usually through representatives, freely chosen, whose actions take place within arenas of conflict, that is , politics , reflecting the differences of view and purpose existing amongst those being represented. Where an elite group governs with slight reference to those governed, the arena of conflict, politics, exists within the elite which acts to suppress opposition to the elite while promoting a consensus that secures the freedom of the elite to act as it sees fit. If politics is at the heart of governments, it is also at the heart of relationships amongst governments. For politics is the organization and application of power to accomplish purpose . Power is the capacity to do work , to accomplish physical changes in the world , to exert force, whether on people or on things. -

16 International Stability

16 Nationalism, Revolutions, and International Stability “Union between the monarchsis the basis of the policy which must now be followed to save society from total ruin.” —Klemens von Metternich, Political Faith, 1820 Essential Question: How did European states struggle to maintain international stability in an age of nationalism and revolution? The balance of power amongcountries in Europe had weakenedin the 1700s, resulting in devastating wars. Following the defeat of Napoleon in 1815, the diplomatic gathering known as the Congress of Vienna attempted to restore that balance. In the Congress,the leaders ofAustria, Great Britain, Prussia, and Russia met under the leadership of Austria’s Klemens von Metternich and formed an alliance. The assembled leaders supported conservative ideals of monarchy rather than constitutional monarchy, hierarchy rather than equality, and tradition rather than reform. Revolutions, War, and Reform Nonetheless, throughout the 1800s, revolutionary movements, nationalistic leaders, and socialist demands challenged conservatism and the balance of power. Bythe late 1800s, nationalism and antagonistic alliances heightened international tensions in Europe directly before World WarI. Revolutions of 1848 While the beginning of the 19th century saw isolated regional resistance movements against conservative governments, 1848 featured an outbreak of revolutions across the continent. These revolutions were spurred by economic hardship andpolitical discontent and caused a breakdown in the Concert of Europeestablished by Metternich at the Congress of Vienna. Revolution Strikes France First When Louis-Philippe became king of France in 1830, he promisedto rule as a constitutional monarch. Yet, as king, he blocked manyattempts at expanding voting rights. In response, opposition 348 AP® EUROPEAN HISTORY WRITE AS A HISTORIAN: EXPLAIN CAUSES Oneof the most basic, and most controversial, skills of a historian is the ability to identify causation, which includes recognizing both causes and effects. -

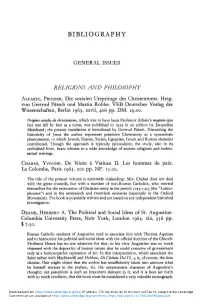

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY GENERAL ISSUES RELIGIONS AND PHILOSOPHY ALFARIC, PROSPER. Die sozialen Urspriinge des Christentums. Hrsg. von Gertrud Patsch und Martin Robbe. VEB Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften, Berlin 1963. xxvii, 406 pp. DM. 29.00. Origines sociales du christianisme, which was to have been Professor Alfaric's magnum opus but was left by him as a torso, was published in 1959 in an edition by Jacqueline Marchand; the present translation is introduced by Gertrud Patsch. Discarding the historicity of Jesus the author represents primitive Christianity as a syncretistic phenomenon, to which Jewish, Essene, Syrian, Egyptian, Greek and Roman elements contributed. Though the approach is typically rationalistic, the study, also in its unfinished form, bears witness to a wide knowledge of ancient religions and ecclesi- astical writings. CHABAS, YVONNE. De Nicee a Vatican II. Les hommes de paix. La Colombe, Paris 1963. 200 pp. NF. 15.00. The title of the present volume is extremely misleading: Mrs. Chabas does not deal with the great councils, but with a number of non-Roman Catholics, who exerted themselves for the restoration of Christian unity in the period 1054-145; (the "Latino- phrones") and in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (especially in the Oxford Movement). The book is popularly written and not based on any independent historical investigation. DEANE, HERBERT A. The Political and Social Ideas of St. Augustine. Columbia University Press, New York, London 1963. xix, 356 pp. Roman Catholic students of Augustine tend to associate him with Thomas Aquinas and to harmonize his political and social ideas with the official doctrine of the Church. -

RETHINKING the ORIGINS of FEDERALISM Puzzle, Theory, and Evidence from Nineteenth-Century Europe

v57.1.070.ziblatt.070-098 6/24/05 10:00 AM Page 70 RETHINKING THE ORIGINS OF FEDERALISM Puzzle, Theory, and Evidence from Nineteenth-Century Europe By DANIEL ZIBLATT* I. INTRODUCTION TATE builders and political reformers frequently seek a federally Sorganized political system. Yet how is federalism actually achieved? Political science scholarship on this question has noted a paradox about federations. States are formed to secure public goods such as common security and a national market, but at the moment a federal state is founded, a dilemma emerges. How can a political core be strong enough to forge a union but not be so powerful as to overawe the con- stituent states, thereby forming a unitary state? This article proposes a new answer to this question by examining the two most prominent cases of state formation in nineteenth-century Europe—Germany and Italy. The aim is explain why these two similar cases resulted in such different institutional forms: a unitary state for Italy and a federal state for Germany.The two cases challenge the stand- ard interstate bargaining model, which views federalism as a voluntary “contract” or compromise among constituent states that is sealed only when the state-building core is militarily so weak that it must grant concessions to subunits. The evidence in this article supports an alternative state-society ac- count, one that identifies a different pathway to federalism. The central argument is that all states, including federations, are formed through a combination of coercion and compromise. What determines if a state is created as federal or unitary is whether the constituent states of a po- tential federation possess high levels of what Michael Mann calls “in- * The author thanks the members of the Comparative Politics Workshop at Yale University, the Comparative Politics Faculty Group at Harvard University, and faculty seminars at George Washington University and Brigham Young University. -

U.S. Army Military History Institute Germany 950 Soldiers Drive Carlisle Barracks, PA 17013-5021 30 May 2012

U.S. Army Military History Institute Germany 950 Soldiers Drive Carlisle Barracks, PA 17013-5021 30 May 2012 THE FULDA GAP A Survey of MHI Sources CONTENTS Since 1945…..p.1 WWII.....p.1 Austro-Prussian War.....p.2 Napoleonic Wars.....p.3 Seven Years War.....p.4 Thirty Years War.....p.4 Pax Romana.....p.5 SINCE 1945 Cook, John L. Armor at Fulda Gap: A Visual Novel of the War of Tomorrow. NY: Avon, 1990. 224 p. PZ4.C645Ar. U.S. Army Engineer Topographic Laboratories. “Effects of Built-up Areas on Armor Operations in the Fulda Corridor: (MOBA Phase II).” Arlington, VA: Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, 1976. 87 p. UG473.G3.E33. WORLD WAR II Near the end of war, when Anglo-American forces raced eastward across Germany toward the Elbe River, the Third U.S. Army swept through the southern part of the Fulda area, early Apr 1945. The First U.S. Army did likewise in the northern end. See: Dyer, George. XII Corps: Spearhead of Patton's Third Army. Baton Rouge: Military Press of LA, 1947. pp. 392, 396, 400 & 402. #04-12- 1947. Gersdorff, Frhr. v. "The Final Phase of the War: From the Rhine to Czech Border." USAREUR Foreign Military Study draft translation, 1946. pp. 1 & 23-33. D739.F6713noA-893. MacDonald, Charles B. The Last Offensive. In USAWWII series. Wash, DC: OCMH, 1973. pp. 374-76. D769A533v3pt9. Fulda Gap p. 2 Shalka, Robert J. “The ‘General-SS’ in Central Germany, 1937-1939: A Social and Institutional Study of SS-Main Sector Fulda-Werra.” PhD dss, U WI, 1972. -

IRE214: CULTURE, SOCIETY and POLITICS in the GERMAN-SPEAKING COUNTRIES Maya Hadar, Phd

IRE214: CULTURE, SOCIETY AND POLITICS IN THE GERMAN-SPEAKING COUNTRIES Maya Hadar, PhD Fall 2019 Session 8: Austrian History Austrian History 2 § Keeping up with the Habsburgs § The Austrian Empire § The Austro-Hungarian Empire § Nationalism § Army § Economy The Habsburgs aka ‘House of Austria’ § One of the most important royal houses of Europe § Best known for being the origin of all Holy Roman Emperors (1438-1740) + all rulers of the Austrian Empire, Spanish Empire and several other countries § The Habsburgs controlled many regions in Europe starting from the 10th Century § Owned territories in Alsace, Switzerland up until the early 20th century The Habsburgs aka ‘House of Austria’ § The House takes its name from the Habsburg Castle, a fortress built around 1020–1030 in present day Switzerland by Count Radbot of Klettgau § His grandson, Otto II, was the first to take the fortress name as his own, adding "von Habsburg" to his title The Habsburgs aka ‘House of Austria’ § The origins of the castle's name are uncertain § Assumed to be derived from the German ‘Habichtsburg’ (Hawk Castle) or from the Middle High German "hab/hap”- ford (brod/river crossing), as there is one nearby § The Habsburg Castle was the family seat in the 11th, 12th and 13th centuries The Habsburgs aka ‘House of Austria’ § The House of Habsburg gathered dynastic momentum in the 11th, 12th and 13th centuries § In 1276, Count Radbot's seventh generation descendant, Rudolph of Habsburg, moved the family's power base from Habsburg Castle to the Archduchy of Austria. § 1273