Katz, Bennett Oral History Interview Jeremy Robitaille

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MLGPA News Periodicals

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons MLGPA News Periodicals 6-2001 MLGPA News (June 2001) David Garrity Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/mlgpa_news Part of the American Politics Commons, American Studies Commons, and the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons Recommended Citation Garrity, David, "MLGPA News (June 2001)" (2001). MLGPA News. 41. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/mlgpa_news/41 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Periodicals at USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in MLGPA News by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. M.aine Lesbian Gay P<>litical Alliance MlG PJt'~News, HARD WORK, VIGILANCE PAYS OFF IN AUGUSTA SPECIAL PRIDE Several major victories move LGBT movement forward EDITION AUG USTA . MLGPA has been wicked single one of their bills has since been ANTl·GAY SEX EDUCATION BILL busy in the State House this session. killed or voted down, including: June 2001 Anti-gay forces from the Right, who The worst bill of the session was LD expected us to be weakened and helpless • A ban °0 gay people from child 1261 , "An Act to Promote Absti- adoptions and foster parenting · s Ed · " d after our loss last November, got a big nence ID ex ucat100, sponsore surprise. This session , MLGPA not only • A block of domestic partnership by Rep . MacDougall (R-Berwick) blocked a number of anti-gay efforts, but benefits for state employees; and Seo . McAlevey (R- York). -

Helping Mainers find Their Way Home

Helping Mainers find their way home. It’s impossible to measure the true impact of a safe, warm, affordable home. Because it does so much more than provide shelter from the storm. It helps us live healthier. Feel more confident. Pursue our dreams. And help others do the same. The Foundation As MaineHousing looks back is Poured on its first 50 years 1969-1972 we’re proud of how we never lost sight of this. Even when the economy was struggling or a project wasn’t panning out, our priority has always been helping In the 1960s, it was easier than ever for tourists Mainers find the living spaces they deserve. to experience the wonders of Vacationland. The This is the real legacy of MaineHousing. Maine Turnpike had been extended to Augusta, Helping people find themselves, after clearing the way for folks “from away.” But for finding their way home. many people living in Maine year-round, and looking for a good home, times were tough. Maine communities asked 1969 – 1972 for housing assistance in MaineHousing’s first year. $ From the start of his term, Curtis advocated for the 96 68,500 creation of a Maine State Housing Authority. And those efforts came to fruition in July 1969, when MaineHousing’s the state legislature passed “An Act to Create a first-year budget State Housing Authority.” The brand-new Housing Authority (MaineHousing) began its first year with a $68,500 budget and five commissioners overseeing it, including its first director, Eben Ewell. By the end of the year, 96 communities had reached out to the new organization for housing assistance. -

2011 Annual Report

Helping women succeed in their workplace, business, and community. 2011 Annual Report Helping to turn “dreams into “I am thankful there is a reality” is what Women, Work, program available to women and Community has been in Maine to help make their doing for over thirty years. dreams a reality. Thank you Whether putting a business plan together, charting a new career path, or gaining control over one’s financial future, we offer tools, for working with me to facilitate learning, and provide connections to resources and get my business up and opportunities. Many of our participants are coping with the loss of running.” a job, a home, a family member or other significant life transition. In their own words, participants let us know the value of what we do, the effect it has on their ability to “create a better future”. In 2008, we began a two year research and evaluation project, funded by the US Department of Labor, to test the notion that setting clear goals and having a plan would result in better outcomes for “I know I am not alone.” the individuals we serve. For the past three years, we have focused (the group) has given me on: delivering core services in the areas of career development, microenterprise, and money management; providing consistent, positive support to keep quality training with clear expectations; and monitoring short-term going towards my goals.” and long term outcomes for program graduates. Preliminary evaluation findings are encouraging: three months after taking a class, participants report the training helped them set goals, they have made progress towards them, and remain confident that they are attainable. -

Hall of Fame Brochure

INDUCTION CEREMONY Maine Women’s Hall of Fame The annual Induction Ceremony held on the third Saturday of March each The Maine Women’s Hall of Fame year is an outstanding public event was founded in 1990 by the Maine when one or two women of Federation of Business and (State) (Zip) (State) achievement are honored. Professional Women. Other co- Each year the ceremony has been sponsors are BPW/Maine Futurama Email: [email protected] Email: Foundation and the University of held at the University of Maine at Augusta during the month of March, Maine at Augusta (UMA). in observance of Women’s History Month. The BPW/Maine Futurama Foundation is establishing the Maine The photographs and citations are on Women’s Hall of Fame Library Books for Library Books permanent display at UMA’s Collection. Books by/about Maine Honoring Maine Women (City) Bennett D. Katz Library. Women’s Hall of Fame inductees and since 1990 Maine women in general are being The impressive Induction Ceremony collected. honors the inductee(s) with a 103 County Road, Oakland, ME 04963 ME Oakland, Road, County 103 Co-Sponsors presentation by family, friends and Email: co-workers, culminating with the presentation of a certificate. Endowment BPW/Maine A Silver Tea is held in conjunction Websites: with the Induction Ceremony to honor our inductee(s). www.bpwmefoundation.org www.uma.edu/community/maine-womens-hall-of-fame/ (Street or P.O. Box) or (Street BPW/Maine Past State Presidents have contributed greatly to the success of the Silver Tea. My check is enclosed. -

See Attachments to Testimony

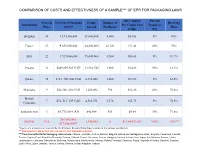

COMPARISON OF COSTS AND EFFECTIVNESS OF A SAMPLE*** OF EPR FOR PACKAGING LAWS 2017 Annual Percent Years in Net Cost of Program People Number of Recovery Jurisdiction Per Capita Cost Taxpayers Place (2017)* Served Producers Rate (USD) Pay Belgium 30 € 144,300,000 11,000,000 5,000 $14.61 0% 80% France 27 € 655,000,000 64,850,000 22,741 $11.42 20% 70% Italy 22 € 524,000,000 55,000,000 8,500 $10.61 0% 69.7% Ontario 16 $249,809,925 CAD 12,962,740 1,800 $14.26 50% 61.3% Quebec 15 $151, 700, 000 CAD 8,316,000 3,400 $13.05 0% 63.6% Manitoba 9 $26,508, 492 CAD 1,206,492 796 $16.26 20% 70.6% British 7 $72, 513, 159 CAD 4,566,371 1,176 $11.75 0% 74.5% Columbia Saskatchewan 3 $5,770,209 CAD 846,804 553 $5.04 25% 72.8% $16,000,000- MAINE N/A 1,340,000 0 $11.04-$13.06* 100% <36%** $17,500,000** *Figures are annual costs reported by the Producer Responsibility Organizations in the various jurisdictions ** Estimates from Maine DEP 2019 Annual Product Stewardship Report. ***Countries with EPR for Packaging Laws include: Albania, Australia, Austria, Belarus, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Brazil, Bulgaria, Cameroon, Canada, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Kosovo, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Macedonia, Moldova, Montenegro, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Republic of Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Tunisia, Turkey, Ukraine, United Kingdom, Vatican Dear Senator Brenner, Representative Tucker, and distinguished members of the Joint Standing Committee on the Environment and Natural Resources, Below is a list of Maine cities and towns, representing more than 325,000 residents from across the state, that have passed resolutions in support of the adoption of an Extended Producer Responsibility for Packaging law to save taxpayers money and improve the effectiveness of recycling as described in LD 1541: An Act To Support and Improve Municipal Recycling Programs and Save Taxpayer Money. -

Deborah Morton Award Ceremony Fiftieth Anniversary Keepsake

ORIGIN DEBORAH MORTON of the Deborah Morton Award (1857-1947) u VOTED: To establish the Deborah Morton Awards to be given by the Board of Trustees of Westbrook Junior / / A scanning of the citations of... honorees reveals College to women of the Greater Portland community who have, in the manner of Deborah Morton, Westbrook an impressive range of leadership and service. The first Deborah Morton Awards were presented on April 20th, 1961, at a Deborah Nichols Morton is a significant figure in institutional histoty. Her Medicine, the law, education, the consular service, public Convocation entitled "The Modern World and the Education of Woman," association with Westbrook Seminary and Junior College, beginning in 1876 as a College and Seminary teacher for more than fifty years, rendered distinguished professional and civic service, y y celebrating the 130th anniversary of the founding of Westbrook Seminary and student and extending to the 1940s, bridged two centuries and survived a crucial religion, social welfare, journalism, politics, period in the life of the college—that of transition from seminary to junior college. • Westbrook Junior College Board of Trustees Minutes Junior College. Mr. William S. Linnell, President of the Boatd of Trustees, assisted 1961 Deborah Morton by college President Edward Y. Blewett, presented the first Awards to twelve women Award Recipients literature, the arts, extraordinary contributions of the Greater Portland area who had made significant and valuable contributions In the March 1964 Westbrook Junior College Alumnae News, Dorothy Healy, whose to the civic, cultural, and social life of the community, in the manner of Deborah own association with Westbrook spanned fifty years and the transition from junior to humane causes are a few among the many The bagpiper pipes as Deborah Morton Morton who had rendered more than fifty yeats of distinguished service to college to college, reminisced about Deborah Morton: iiSSfl r jSi awardees and their escorts line up for the areas of life on which these.. -

Maine State Legislature

MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE The following document is provided by the LAW AND LEGISLATIVE DIGITAL LIBRARY at the Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library http://legislature.maine.gov/lawlib Reproduced from electronic originals (may include minor formatting differences from printed original) LAWS OF THE STATE OF MAINE AS PASSED BY THE ONE HUNDRED AND SEVENTEENTH LEGISLATURE SECOND SPECIAL SESSION September 5, 1996 to September 7, 1996 ONE HUNDRED AND EIGHTEENTH LEGISLATURE FIRST REGULAR SESSION December 4, 1996 to March 27, 1997 FIRST SPECIAL SESSION March 27, 1997 to June 20, 1997 THE GENERAL EFFECTIVE DATE FOR FIRST REGULAR SESSION NON-EMERGENCY LAWS IS JUNE 26, 1997 FIRST SPECIAL SESSION NON-EMERGENCY LAWS IS SEPTEMBER 19, 1997 PUBLISHED BY THE REVISOR OF STATUTES IN ACCORDANCE WITH MAINE REVISED STATUTES ANNOTATED, TITLE 3, SECTION 163-A, SUBSECTION 4. J.S. McCarthy Company Augusta, Maine 1997 CIVIL GOVERNMENT OF THE STATE OF MAINE FOR THE POLITICAL YEARS 1997 AND 1998 CONSTITUTIONAL OFFICERS Governor Angus S. King, Jr. Secretary of State Dan A. Gwadosky Attorney General Andrew Ketterer Treasurer of State Dale McCormick State Auditor Gail M. Chase IX EXECUTIVE BRANCH STATE DEPARTMENTS Governor Angus S. King, Jr. Administrative and Financial Services, Department of Human Services, Department of Commissioner .......................................... Janet Waldron Commissioner ................................... Kevin Concannon Agriculture, Food and Rural Resources, Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife, Department of Commissioner -

2010 Archive of Governor Baldacciâ•Žs Press Releases

Maine State Library Digital Maine Governor's Documents Governor 2010 2010 Archive of Governor Baldacci’s Press Releases Office of veGo rnor John E. Baldacci Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalmaine.com/ogvn_docs Recommended Citation Office of Governor John E. Baldacci, "2010 Archive of Governor Baldacci’s Press Releases" (2010). Governor's Documents. 11. https://digitalmaine.com/ogvn_docs/11 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Governor at Digital Maine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Governor's Documents by an authorized administrator of Digital Maine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2010 Archive of Governor Baldacci’s Press Releases Compiled by the Maine State Library for the StateDocs Digital Archive with the goal of preserving public access and ensuring transparency in government. 2010 Archive of Governor Baldacci’s Press Releases Table of Contents Governor Baldacci Names Elizabeth Townsend Acting Commissioner of the Department of Conservation .................................................................................................................................................................... 10 Governor Names MaineHousing, Dirigo Health and Maine Retirement System Nominees ...................... 11 Governor to Deliver State of the State Address on January 21 .................................................................. 13 Maine Companies Awarded Energy Efficiency Grants ............................................................................... -

Magazine Winter 2011

UNIVERSITY OF NEW ENGLAND MAGAZINE WINTER 2011 Celebrating Leadership Deborah Morton Society 50th Convocation FOR ALUMNI & FRIENDS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW ENGLAND, WESTBROOK COLLEGE AND ST. FRANCIS COLLEGE UNIVERSITY OF NEW ENGLAND 1 PRESIDENT’S LETTER 2011: A YEAR OF MAINE EXPERIENCES, GLOBAL EXPLORATIONS President Danielle N. Ripich, Ph.D. DURING THIS TRADITIONAL SEASON OF CELEBRATING AND GIVING THANKS, UNE HAS MANY REASONS TO BE GRATEFUL. IT HAS BEEN AN EXCITING YEAR OF ACCOMPLISHMENTS, AND WE MARKED MANY NOTEWORTHY “FIRSTS” IN 2011: • We broke ground on our $20 million Harold Alfond Forum, which will become But it’s far more than being “first” that the largest gathering place on campus when it opens in 2012. matters. We continue to innovate, creating new models of education that will prepare our • Our Master of Public Health program received accreditation from the Council students to succeed in a more competitive, on Education for Public Health, making it the first accredited MPH program in globally and technologically connected work- the state of Maine. place. UNE is emerging nationally as a leader in health care education. We are making our • We completed the renovation of historic Goddard Hall, the new administrative curriculum portable, so UNE students can take home of UNE’s College of Dental Medicine, the first dental school in northern it with them whether they spend a semester New England. across the country or across the globe. • The UNE College of Pharmacy became the first accredited provider of continuing UNE is poised to enter 2012 on course to pharmacy education in northern New England. -

Catalog 2003-2004

Catalog 2003-2004 Notice of Non-Discrimination It is the policy of Central Maine Technical College to comply with all federal and state laws and regulations which prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, national origin or citizen status, age, handicap, marital or veteran's status in admis- sion to, access to, treatment in or employment in its programs and activities. Upon request, the College provides reasonable accommodations to individuals with documented disabilities. Inquiries regarding these policies should be directed to the CMTC affirmative action officer, 1250 Turner Street, Auburn, ME 04210-6498, 207/755-5275. Inquiries concerning the application of nondiscrimination policies may also be referred to the Regional Director, Office for Civil Rights, U.S. Department of Education, J.W. McCormack P.O.C.H., Room 222, Boston, MA 02109-4557. The College’s most recent audited financial statement or a fair summary thereof is available, upon request, in the business office during normal business hours. Central Maine Technical College, Copyright 2003 Mission . .ii General Information . .1 President’s Message . .2 Accreditation . .2 Executives-in-Residence . .3 About CMTC . .3 Admissions . .7 Tuition & Fees . .13 Financial Aid . .17 Student Services . .21 Academic Affairs . .27 Policies and Procedures . .28 Academic Services . .34 Programs of Study . .37 Program and Course Abbreviations and Titles . .39 Accounting . .40 Applied Technical Studies . .41 Architectural & Civil Engineering Technology . .42 Automotive Technology . .43 Automotive Technology — Ford ASSET . .44 Automotive Technology — Parts & Service Management . .45 Building Construction Technology . .47 Business Administration & Management . .49 Business and Computer Applications . .52 Clinical Laboratory Science . -

Legislative Record - Senate, Wednesday, March 19, 2014

LEGISLATIVE RECORD - SENATE, WEDNESDAY, MARCH 19, 2014 STATE OF MAINE ONE HUNDRED AND TWENTY-SIXTH LEGISLATURE Out of order and under suspension of the Rules, the Senate SECOND REGULAR SESSION considered the following: JOURNAL OF THE SENATE ORDERS In Senate Chamber Wednesday Joint Order March 19, 2014 Expressions of Legislative Sentiment recognizing: Senate called to order by President Pro Tem John J. Cleveland of Androscoggin County. The late Richard D. Dutremble, of Biddeford, on his posthumous induction into the Franco-American Hall of Fame. Richard _________________________________ Dutremble was born in Biddeford, the last of 13 children of Honore and Rose Anna Dutremble, and served in the United Prayer by Reverend Paul Plante, Our Lady of the Lakes in States Army in Germany. He and his brother Lucien Dutremble Oquossoc. were partners in the grocery store business, owning Dutremble Brothers Market in Biddeford. Richard Dutremble was elected REVEREND PLANTE: May we join our hearts and minds Sheriff of York County and served for 15 years, from 1962 to together in prayer. Prions le Seigneur, Dieu createur de tout ce 1977. He was appointed United States Marshall for the State of qui est bon, de tout ce qui est beau, nous vous remorcions Maine under President Jimmy Carter's administration and later arjourd hin pourla divers je culturelle dent nous jouissons dans served as Director of Civil Emergency Preparedness during notre etat du Maine, en particulier pour tout ce quela culture Governor Joe Brennan's terms in office. He returned to law francaise a contribute pour nous enrichin, que ce soit la vanete enforcement and followed in his father's footsteps, serving as a des accents et des expressions, venant des pays de langue Biddeford police officer until his retirement in 1992. -

Funding Women and Girls ( 2002 - Fall)

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine Women's Publications - All Publications Fall 9-1-2002 Funding Women and Girls ( 2002 - Fall) Maine Women's Fund Staff Maine Women's Fund Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/maine_women_pubs_all Part of the History Commons, Public Administration Commons, Public Affairs Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Repository Citation Staff, Maine Women's Fund, "Funding Women and Girls ( 2002 - Fall)" (2002). Maine Women's Publications - All. 56. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/maine_women_pubs_all/56 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine Women's Publications - All by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Womefundingn and Girls STELLA LADO ALEXANDRA MERRILL “Her arms are always open wide with “She is a fully embodied woman, un love.” Although she does not call her afraid to stand up and speak about the self a leader, Stella Lado has become most unspeakable issues surrounding a compelling force for cross-cultural sexism, racism, classism, homophobia, understanding in her neighborhood, heterosexism, ageism, fat and thinnism, her school, and in a Portland which is as well as spiritual and ethnic differences becoming increasingly diverse. “Her ... no other teacher has inspired me and leadership and mentoring never deepened my understanding of misogyny ends,” writes a nominator. “Stella and feminism.” These remarks from a truly cares about the children in her nominator, extraordinary as they are, community ... When Stella speaks, give only a partial picture of Alexandra they listen!” Stella has learned about Merrill’s accomplishments, and her im cultural diversity by living it: she and pact on the lives of women and girls.