D Evelop M Ent Policy O F Four U .S . Cities Randolph, Lewis Anthony, Ph

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

0708Mbkbnotes Game 8 Villanova.Qxd

THE BRADY ERA | 11th SEASON, 6 POSTSEASON TOURN., 3 WESTERN DIV. and 2 SEC TITLES; 2006 FINAL 4 LSU Fighting Tigers (5-2) vs. Villanova Univ. (5-1) in Pizza Hut Big East/SEC Inv. Dec. 6, 2007, 9:30 p.m. EST (8:30 CST) (LSU Sports Radio Network, ESPN) Wachovia Center -- Philadelphia, Pa. 2007-08 Schedule Projected LSU Starters and Notes OPPONENT TIME N1 BELHAVEN (Exh.) W, 108-57 G 5 Marcus Thornton (6-4, 190, Jr., Baton Rouge) 19.9 ppg, 5.0 rpg N6 GLOBAL SPORTS (Exh.) W, 72-68 Had his sixth 20-point game and second in succession with 22 against Southern (11/30) after N12 SOUTHEASTERN LA. (CST) W, 72-62 24 against Nicholls State (11/28) ... 20 treys ... Team leader in minutes player at 34.0 mpg. N14 MCNEESE STATE (CST) W, 78-74 N19 1-Oklahoma State (ESPN2) L, 77-83 G 13 Terry Martin (6-6, 200, Jr., Monroe, La.) 7.6 ppg, 4.7 rpg N20 1-Chaminade (ESPNU) W, 78-72 Started all seven games, plays primary minutes this year at point guard after playing last sea- N21 1-Arizona State (ESPN2) (ot) L, 84-87 son at off guard ... Hit 52 treys last year ... Still trying to find range this year, 8-32 from arc (25%). N28 NICHOLLS STATE (CST) W, 68-41 N30 SOUTHERN W, 88-45 C 21 Chris Johnson (6-11, 205, Jr., Montross, Va.) 12.9 ppg, 5.3 rpg, 2.4 bpg D6 2-Villanova (ESPN) 8:30 p.m. Career high and fifth straight double figure scoring game with 20 against Southern (11/30) .. -

LSU Basketball Vs

THE BRADY ERA | In 10th YEAR, 6 POSTSEASON TOURN., 3 WESTERN DIV. and 2 SEC TITLES; 2006 FINAL 4 LSU Basketball vs. University of Connecticut January 6, 2007, 8 p.m. CST (LSU Sports Radio Network, ESPN) Pete Maravich Assembly Center -- Baton Rogue, La. LSU (10-3) Probable LSU Starters (based on the last game): G -- 2Dameon Mason (6-6, 183, Jr., Kansas City, Mo.) 8.0 ppg, 3.5 rpg, 1.2 apg NOVEMBER Mason started last four games, 11 in all this season ... Had 14, 13 and 11 points during the three games of the 9 E. A. Sports (Exh.) W, 70-65 HCF Classic ... 14 vs. Wright State (12/27) season est ... Out of starting lineup against Oregon State (12/17) 15 Louisiana College (Exh.) W, 94-41 and Washington (12/20) because of migraines ... Five total games scoring in double figures. 17 Nicholls State W, 96-42 19 Louisiana-Monroe (CST) W, 88-57 G -- 14 Garrett Temple (6-5, 190, So., Baton Rouge, La.) 10.2 ppg, 2.8 rpg, 4.1 apg 25 #24 Wichita State (CST) L, 53-57 Six games in double figures ... Had career highs of seven assists in back-to-back games of HCF Classic (Miss. 29 McNeese State (CST) W, 91-57 Valley, 12/28; Samford 12/29) with just five combined turnovers ... In first seven games had 23 assists and just DECEMBER 7 turnovers ... Career high of 18 at Tulane (12/2) with 17 vs. McNeese (11/29) and at Oregon State (12/17) ... 2 At Tulane (1) W, 74-67 Earned reputation as defensive stopper after holding Duke’s J.J. -

THE TUFTS DAILY Est

Where You Partly Cloudy Read It First 70/54 THE TUFTS DAILY Est. 1980 VOLUME LXV, NUMBER 55 FRiday, APRIL 19, 2013 TUFTSDAILY.COM TEX talks discuss topics from Nickelback to social media BY ANNA KELLY cal engineer who spoke about natural and Contributing Writer sustainable medical materials. During her talk, Bhatia argued that the western world How would you design the social struc- has to rethink its relationship with medicine ture of a colony on Mars? How can social in developing countries. media define a company, and how does it “People in developing countries are smart define you? Are you a music snob? and want to use the resources they have to These were just a few of the questions address medical issues,” she said. posed to audience members by the speak- Bhatia went on to discuss the possible ers at last week’s Tufts Idea Exchange (TEX) intersection of agriculture and medicine if event. Inspired by TED, the nonprofit organi- these new medical materials were intro- zations that coordinates conferences devot- duced because materials needed to treat ed to the spread of ideas, TEX was founded those who were ill could be grown in devel- in 2011 to create a forum for Tufts students oping countries and be utilized there. to share their own original and thought pro- The first student to speak, junior Michael voking ideas through ten minute speeches. Grant, began his talk with a confession. Each year, the event is co-sponsored by the “I actually listened to an entire Nickelback Institute for Global Leadership and Synaptic CD,” he said. -

2013-14 Panini Crusade Basketball Set Checklist Base Set Checklist

2013-14 Panini Crusade Basketball Set Checklist Base Set Checklist 100 cards PARALLEL CARDS: Silver #/25, Gold #/10, Black 1/1 1 Chris Paul 2 Al Horford 3 Pau Gasol 4 Nikola Vucevic 5 Monta Ellis 6 Tyreke Evans 7 Rajon Rondo 8 Carmelo Anthony 9 Kevin Love 10 Andre Drummond 11 J.J. Redick 12 Jeff Teague 13 Steve Nash 14 Jameer Nelson 15 Dirk Nowitzki 16 Amir Johnson 17 Jeff Green 18 Tyson Chandler 19 Kevin Martin 20 Luol Deng 21 Goran Dragic 22 Nick Young 23 Paul Millsap 24 Tony Parker 25 Shawn Marion 26 Spencer Hawes 27 Jordan Crawford 28 Andrea Bargnani 29 Derrick Favors 30 Derrick Rose 31 Eric Bledsoe 32 DeMarcus Cousins 33 Kemba Walker 34 Tim Duncan 35 Vince Carter 36 Wesley Matthews 37 DeMar DeRozan 38 Damian Lillard 39 Enes Kanter 40 Carlos Boozer 41 Gerald Green 42 Isaiah Thomas 43 Gerald Henderson 44 Manu Ginobili 45 Mike Conley 46 Nicolas Batum 47 Kyle Lowry 48 LaMarcus Aldridge 49 Gordon Hayward 50 Kyrie Irving 51 Stephen Curry 52 Rudy Gay 53 Al Jefferson 54 Kawhi Leonard 55 Zach Randolph 56 J.J. Hickson 57 Evan Turner 58 Kevin Durant 59 Paul George 60 Dion Waiters 61 Klay Thompson 62 LeBron James 63 John Wall 64 James Harden 65 Marc Gasol 66 Ricky Rubio 67 Thaddeus Young 68 Russell Westbrook 69 David West 70 Tristan Thompson 71 David Lee 72 Chris Bosh 73 Marcin Gortat 74 Dwight Howard 75 Eric Gordon 76 Caron Butler 77 Kevin Garnett 78 Serge Ibaka 79 Roy Hibbert 80 O.J. -

The Williams File Williams and the Ncaa Tournament

1 2 3 4 1100 RaymoneR Andrews KentwanK t Smith WillieWilli Green B.J.BJ GGlasford HunterH t MMiller G • 6-2 • 180 • Sr. F • 6-8 • 205 • Jr. F • 6-6 • 210 • Sr. G • 6-4 • 180 • Fr. G • 6-2 • 180 • Sr. Hammond, La. Freeport, Bahamas Orlando, Fla. Miami, Fla. Nashville, Tenn. 1111 1122 1155 2211 2222 AaronA GGraham RaekwonRk Harney AidanAid Hadley H AndrewAd Zelis TannerT PPlemmonsl G • 6-4 • 175 • Sr. G • 5-11 • 165 • Fr. F • 6-5 • 190 • So. C • 6-11 • 240 • Fr. G • 6-2 • 190 • So. Miramar, Fla. Winston-Salem, N.C. Owls Head, Maine Wheaton, Ill. Franklin, N.C. 2233 2244 3333 4400 4411 LekeL k SolankeS l CameronC HHarvey GlennGl BBaral KyleK l SikoraSik BrianB i Pegg F • 6-6 • 215 • So. G • 6-3 • 210 • So. G • 6-3 • 205 • Fr. C • 7-0 • 255 • Jr. F • 6-7 • 205 • R-Fr. Abeokuta, Nigeria Naperville, Ill. Richmond, Calif. Key Largo, Fla. Clearwater, Fla. Corey Williams Mike Jaskulski Nikita Johnson Bert Capel Kevin Dux Head Coach Assistant Coach Assistant Coach Assistant Coach Director of Ops First Year First Year First Year First Year First Year S SEASON PREVIEW STETSON BASKETBALL E A S O N TABLE OF CONTENTS P R E SEASON PREVIEW Leke Solanke ...............................30-31 Letterwinners ...............................53-55 V I Table of Contents ................................1 Cameron Harvey ...............................32 Vs. Opponents ............................56-57 E Media Information ..............................2 Aidan Hadley ....................................33 Yearly Summary ................................58 W Quick Facts ...........................................3 Brian Pegg ...................................34-35 Roster ..................................................... 4 Glenn Baral ........................................36 STETSON UNIVERSITY Schedule .............................................. -

Table of Conents/Credits

Table of Conents/Credits INTRO THIS IS LSU TIGERS COACHES REVIEW PREVIEW RECORDS HISTORY LSU MEDIA Intro The Tigers Preview History 2 Quick Facts 58 Alex Farrer 109 EA Sports Maui Invitational 147 Yearly Records/Milestones 3 2007-08 Schedule/2006-07 Results 59 Chris Johnson 110 Non-Conference Opponents 148 Home-Away-Neutral 4 2007-08 Rosters 61 Terry Martin 113 SEC Office 149 Year-by-Year Results 5 Roster Breakdown 63 Dameon Mason 114 SEC TV Schedule/LSU on TV 158 Series Records 6 2007-08 Season Preview 65 Tasmin Mitchell 115 Alabama, Arkansas, Auburn, Florida 168 Championship Teams 68 Garrett Temple 116 Georgia, Kentucky, Ole Miss, 170 Record vs. Conferences This is LSU 71 Greg Terrebonne Miss. State 171 LSU in the Postseason 72 Garrett Green/Anthony Randolph 117 South Carolina, Tennessee, 173 LSU in the APPoll 8 Player Development 73 Bo Spencer/Marcus Thornton Vanderbilt, Series Records vs. 2007- 177 SEC Championships 10 Championship Basketball 74 Quintin Thornton 08 SEC Opp. 178 Brady Era Statistics 12 Cox Communications Academic 75 Returning Player Stats 118 Postseason Dates, Travel Plans 180 100-Point Games Center 76 Radio/TV Roster 119 SECTournament 181 Overtime Games 16 Campus Life 182 Pete Maravich Assembly Center 19 Campus Apartments 184 All-SEC Teams 20 Giving Back Coaches Records 187 Harry Rabenhorst 21 Career Development/CHAMPS 77 Coaches of the SEC Era 121 School Records 188 Dale Brown 22 City of Baton Rouge 78 All-Time Coaching Records 124 Maravich CenterRecords 189 Lettermen 23 State of Louisiana 79 Head Coach John Brady -

Blake Griffin by Caleb Murphy 5-B Coming out of Oklahoma University, Blake Griffin Was the First Pick of the 2009 NBA Draft by the Los Angles Clippers

February 2011 Layout: Isaac Frumkin SPORTS XTREME Contents Super Bowl.................p.1 Carmelo Trade............p.2 Blake Griffin................p.2 All-Star Weekend........p.3 Fired Coaches............p.4 Indoor Track...............p. 5 Flyers and Penguins...p.5 Redskins Wrap-Up.....p.6 Lafayette Bears..........p.6 Caps Win...................p. 7 Super Bowl XLV College Bowls.............p.8 by Isaac Frumkin 5-J Rothlisberger completed an 8 yard pass to Hines On February 6th, the Green Bay Packers and the Ward for the touchdown. GB 21-10. Pittsburgh Steelers battled each other for the Super Bowl Title. You may have watched it at The only scoring in the third quarter was for the home or you might have watched it at a party, but Steelers. Rashard Mendenhall ran for 8 yards and no matter where you saw it, you saw one of the the touchdown. GB 21-17. Early in the fourth most exciting games ever. quarter, Clay Matthews forced a fumble and Green Bay recovered. They went on to score on Nick Collins celebrates After Christina Aguilera messed up the National an 8-yard completion to Gregg Jennings. GB his pick and TD. Anthem, the game began. It took a little while for 28-17. the teams to start scoring, but with 3:44 left in the first quarter it started. Aaron Rodgers threw a 29- When the Steelers got the ball, they didnʼt waste yard completion to Jordy Nelson for the first the opportunity to pull close. Ben Rothlisberger touchdown of the game. GB 7-0. Twenty-four threw a 25 yard pass to Mike Wallace for the seconds later the Packersʼ safety, Nick Collins, touchdown. -

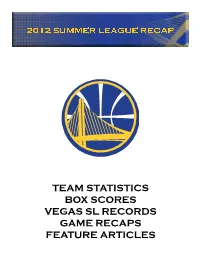

Team Statistics Box Scores Vegas Sl Records Game

TEAM STATISTICS BOX SCORES VEGAS SL RECORDS GAME RECAPS FEATURE ARTICLES WARRIORS FINAL SUMMER LEAGUE ROSTER WARRIORS SUMMER LEAGUE RESULTS NO PLAYER POS HT WT DOB PRIOR TO NBA/FROM NBA EXP. DATE OPPONENT RESULT SCORE HIGH POINTS/REBOUNDS/ASSISTS OPPS HIGH POINTS/REBOUNDS/ASSISTS July 13 vs. LA Lakers W 90-50 Thompson 24/Green 9/Thompson 5 Goudelock 14/Majok 7/Morris 4 40 Harrison Barnes F 6-8 210 5/30/92 North Carolina/USA R July 14 vs. Denver W 95-74 Jenkins 24/Barnes & Ezeli 7/Thompson 4 Hamilton 18/Faried 8/Faried 3 July 18 vs. Miami W 65-62 Jenkins 17/Barnes 7/Three Players 2 Cole 15/Viney 8/Cole 4 20 Kent Bazemore G/F 6-5 195 7/1/89 Old Dominion/USA R July 20 vs. Chicago W 66-57 Barnes 20/Green 11/Ragland 3 Teague & Thomas 12/Thomas 16/Four Players 2 25 Justin Burrell F 6-8 244 4/18/88 St. John’s/USA R July 21 vs. New Orleans W 80-72 Jenkins 15/Three Players 6/Jenkins 4 Henry 21/Thomas 8/Roberts 5 31 Festus Ezeli C 6-11 255 10/21/89 Vanderbilt/Nigeria R 23 Draymond Green F 6-7 230 3/4/90 Michigan State/USA R WARRIORS SUMMER LEAGUE STATS 22 Charles Jenkins G 6-3 220 2/28/89 Hofstra/USA 1 PLAYER G GS MIN FGM FGA PCT 3FGM 3FGA PCT FTM FTA PCT OFF DEF TOT AST PF DQ STL TO BLK PTS AVG Klay Thompson 2 2 59 14 27 .519 10 14 .714 3 4 .750 2 10 12 9 5 0 3 9 3 41 20.5 52 Dallas Lauderdale F 6-8 260 9/11/88 Ohio State/USA R Harrison Barnes 5 5 168 30 76 .395 8 14 .571 16 22 .727 10 18 28 2 11 0 9 7 0 84 16.8 21 Joe Ragland G 6-0 185 11/11/89 Wichita State/USA R Charles Jenkins 5 5 139 22 43 .512 0 2 .000 27 28 .964 0 7 7 14 6 0 8 14 0 71 14.2 -

0708Mbkbnotes Game 21 Alabama.Qxd

THE BRADY ERA | 11th SEASON, 6 POSTSEASON TOURN., 3 WESTERN DIV. and 2 SEC TITLES; 2006 FINAL 4 LSU Fighting Tigers (8-12, 1-5) at University of Alabama (12-9, 1-5) February 2, 2008, 2 p.m. CST (LSU Sports Radio Network, Raycom Sports) Coleman Coliseum -- Tuscaloosa, Ala. 2007-08 Schedule Projected LSU Starters and Notes (based on last game): OPPONENT TIME G 5 Marcus Thornton (6-4, 190, Jr., Baton Rouge) 19.7 ppg, 6.0 rpg N1 BELHAVEN (Exh.) W, 108-57 His fifth consecutive game over 20 points turned out to be the highest scoring game in 13 years in the N6 GLOBAL SPORTS (Exh.) W, 72-68 league as Thornton scored 38 at Auburn (1/30) with eight treys, including the game winner with 3.8 N12 SOUTHEASTERN LA. (CST) W, 72-62 seconds to play ... 12 games of 20 or more ... 24.8 ppg in conference games. N14 MCNEESE STATE (CST) W, 78-74 N19 1-Oklahoma State (ESPN2) L, 77-83 G 14 Garrett Temple (6-6, 185, Jr., Baton Rouge, La.) 6.8 ppg, 4.0 rpg, 3.5 apg Primary point guard, has already broken into schaool top 10 lists in career assists, blocks ...Had team N20 1-Chaminade (ESPNU) W, 78-72 high eight rebounds with seven assist and just one turnover in 39 minutes at Auburn (1/30). N21 1-Arizona State (ESPN2) (ot) L, 84-87 N28 NICHOLLS STATE (CST) W, 68-41 G 30 Alex Farrer (6-5, 200, So., Phoenix, Ariz.) 2.8 ppg, 1.4 rpg N30 SOUTHERN W, 88-45 Started his fourth game of the season at Auburn (1/30) .. -

Memphis Grizzlies 2016 Nba Draft

MEMPHIS GRIZZLIES 2016 NBA DRAFT June 23, 2016 • FedExForum • Memphis, TN Table of Contents 2016 NBA Draft Order ...................................................................................................... 2 2016 Grizzlies Draft Notes ...................................................................................................... 3 Grizzlies Draft History ...................................................................................................... 4 Grizzlies Future Draft Picks / Early Entry Candidate History ...................................................................................................... 5 History of No. 17 Overall Pick / No. 57 Overall Pick ...................................................................................................... 6 2015‐16 Grizzlies Alphabetical and Numerical Roster ...................................................................................................... 7 How The Grizzlies Were Built ...................................................................................................... 8 2015‐16 Grizzlies Transactions ...................................................................................................... 9 2016 NBA Draft Prospect Pronunciation Guide ...................................................................................................... 10 All Time No. 1 Overall NBA Draft Picks ...................................................................................................... 11 No. 1 Draft Picks That Have Won NBA -

Arizonawildcats

ARIZONA WILDCATS EDITIONE ARIZONA DAILY STAR | SUNDAY, JANUARY 5, 2020 | PAGE AB1 E X T R A Editor: Ryan Finley | 520-573-4312 | [email protected] NO. 25 ARIZONA 75, ARIZONA STATE 47 MESSAGE RECEIVED KELLY PRESNELL / ARIZONA DAILY STAR Arizona guard Josh Green dunks to end a fast break in the Wildcats’ 75-47 win over visiting Arizona State on Saturday night at McKale Center. UA hadn’t played a game in 14 days. Rested UA runs ASU off court in 28-point win By Bruce Pascoe — a miss — after Miller said before in double figures with Mannion ARIZONA DAILY STAR UP NEXT the game that he could make the PAC-12 STANDINGS and Dylan Smith adding 10 points Stop taking silly shots. Feed • Who: No. 25 Arizona (11-3, 1-0) case that anyone shooting 32 per- Team Conf. Overall each, while 10 total players scored. Zeke. Don’t foul so much. Re- at No. 4 Oregon (12-3, 1-1) cent should never take such a shot Colorado 1-0 12-2 They were fast, but not too fast bound. • When: 7 p.m. Thursday (Green was hitting 32.5% from 3). Stanford 1-0 12-2 for Miller’s liking. Play for Arizona, not yourself. • TV: ESPN or ESPN2 Instead, Green picked up his USC 1-0 12-2 “We want to play at a fast tem- On and on and on came Sean • Radio: 1290-AM, 107.5-FM points where he gets them the Arizona 1-0 11-3 po … it makes sense with Nico Miller’s messages, to the media best, on the break. -

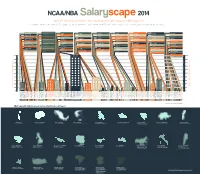

A Complete Breakdown of Every NBA Player's Salary, Where They

$1,422,720 (DonatasMotiejunas,Houston) $3,526,440 (JonasValanciunas,Toronto) Lithuania: $4,949,160 $12,350,000 (SergeIbaka,OklahomaCity) $3,049,920 (BismackBiyombo,Charlotte) Congo: $15,399,920 Total Salaries of Players that Schools Produced in Millions of US Dollars 100M 120M 140M 160M 180M 200M NBA Salary Distribution by Country that Produced Players SalaryDistributionbyCountrythatProduced NBA 20M 40M 60M 80M 947,907 (OmriCasspi,Houston) Israel: $947,907 0M 3 $10,105,855 |Gerald Wallace, Boston $3,250,000 |Alonzo Gee, Cleveland $2,652,000 |Mo Williams, Portland $3,135,000 |Jerryd Bayless, Boston Arizona $1,246,680 |Solomon Hill, Indiana $12,868,632 |Andre Iguodala, Golden State $3,500,000 |Jordan Hill, LA Lakers 10 $6,400,000 |Channing Frye Phoenix $5,625,313 |Jason Terry, Sacramento $5,016,960 |Derrick Williams, Sacramento $5,000,000 |Chase Budinger, Minnesota $226,162 |Mustafa Shaku, Oklahoma City $11,046,000 |Richard Jefferson, Utah Butler Bucknell Brigham Young Boston College Blinn College|$1.4M Belmont |$0.5M Baylor |$7.1M Arkansas-LR |$0.8M Arkansas |$23.1M Arizona State|$16M Arizona |$54M Alabama |$16M 3 $510,000 |Carrick Felix, Cleveland $13,701,250 |James Hardin, Houston $1,750,000 |Jeff Ayres, San Antonio 3 21,466,718 |Joe Johnson 884,293 |Jannero Pargo, Charlotte 1 788,872 |Patrick Beverey, Houston 884,293 |Derek Fisher, Oklahoma City A completebreakdownofeveryNBAplayer’ssalary,wheretheyplayedbeforetheNBA,andwhichschoolscountriesproducehighestnetsalary. 4 4,469,548 |Ekpe Udoh, Milwaukee 788,872 |Quincy Acy, Sacramento 788,872