(Tamils – LP Updated) Sri Lanka CG [2009] UKAIT 00049

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tender ID Link to Download Information Copy of Addendum 1

Distribution Division 02 Link to download Area Tender ID information copy of Addendum 1 DGM (East)/Area(Trincomalee)/ CSC(Trinco Town)/001/ ETD 154 Click Here DGM (East)/Area(Trincomalee)/ CSC(Kanthale)/002/ ETB 080 Click Here DGM (East)/Area(Trincomalee)/ CSC(Kanthale)/003/ ETB 024 Click Here DGM (East)/Area(Trincomalee)/ CSC(Kanthale)/004/ ETB 025 Click Here DGM (East)/Area(Trincomalee)/ CSC(Kanthale)/005/ ETB 045 Click Here DGM (East)/Area(Trincomalee)/ CSC(Kanthale)/006/ ETB 009 Click Here DGM (East)/Area(Trincomalee)/ CSC(Kanthale)/007/ ETB 062 Click Here DGM (East)/Area(Trincomalee)/ CSC(Kanthale)/008/ ETB 023 Click Here DGM (East)/Area(Trincomalee)/ CSC(Kanthale)/009/ ETB 079 Click Here DGM (East)/Area(Trincomalee)/ CSC(Kanthale)/010/ ETB 002 Click Here Trincomalee DGM (East)/Area(Trincomalee)/ CSC(Kanthale)/011/ ETB 068 Click Here DGM (East)/Area(Trincomalee)/ CSC(Kanthale)/012/ ETB 003 Click Here DGM (East)/Area(Trincomalee)/ CSC(Kanthale)/013/ ETB 047 Click Here DGM (East)/Area(Trincomalee)/ CSC(Kinniya)/014/ ETE 055 Click Here DGM (East)/Area(Trincomalee)/ CSC(Kinniya)/015/ ETE 013 Click Here DGM (East)/Area(Trincomalee)/ CSC(Kinniya)/016/ ETE 032 Click Here DGM (East)/Area(Trincomalee)/ CSC(Kinniya)/017/ ETE 009 Click Here DGM (East)/Area(Trincomalee)/ CSC(Kinniya)/018/ ETE 037 Click Here DGM (East)/Area(Trincomalee)/ CSC(Kinniya)/019/ ETE 030 Click Here DGM (East)/Area(Trincomalee)/ CSC(Kinniya)/020/ ETE 036 Click Here Link to download Area Tender ID information copy of Addendum 1 DGM (East)/Area(Batticaloa)/CSC(Vaharai)/001/ -

(Lates Calcarifer) in Net Cages in Negombo Lagoon, Sri Lanka: Culture Practices, Fish Production and Profitability

Journal of Aquatic Science and Marine Biology Volume 1, Issue 2, 2018, PP 20-26 Farming of Seabass (Lates calcarifer) in net cages in Negombo Lagoon, Sri Lanka: Culture practices, fish production and profitability H.S.W.A. Liyanage and K.B.C.Pushpalatha National Aquaculture Development Authority of Sri Lanka, 41/1, New Parliament Road, Pelawatta, Battaramulla, Sri Lanka *Corresponding Author: K.B.C.Pushpalatha, National Aquaculture Development Authority of Sri Lanka, 41/1, New Parliament Road, Pelawatta, Battaramulla, Sri Lanka. ABSTRACT Shrimp farming is the main coastal aquaculture activity and sea bass cage farming also recently started in Sri Lanka. Information pertaining to culture practices, fish production, financial returns and costs involved in respect of seabass cage farms operate in the Negombo lagoon were collected through administering a questionnaire. The survey covered 13 farms of varying sizes. The number of cages operated by an individual farmer or a family ranged from 2 – 13. Almost all the farmers in the lagoon used floating net cages, except for very few farmers, who use stationary cages. Net cages used by all the farmers found to be of uniform in size (3m x 3m x 2m) and stocking densities adapted in cages are also similar. Production of fish ranged between 300 to 400 Kg per grow-out cage. All seabass farmers in the Negombo lagoon entirely depend on fish waste/trash fish available in the Negombo fish market to feed the fish. Availability of these fish waste/trash fish at no cost to the farmers has made small scale seabass farming financially very attractive. -

Epidemiological Bulletin Sri Lanka

Veterinary Epidemiological Bulletin Sri Lanka Volume 6 No 01 ISSN:1800-4881 January - March 2013 Department of Animal Production and Health, P.O.Box 13, Peradeniya, Sri Lanka. [email protected] Contents Control of Infectious Bursal 1 Control of Infectious Bursal Disease Disease (Gumboro) (Gumboro) 1.1 Introduction 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Epidemiology 1.3 Clinical Signs Infectious Bursal Disease (IBD) is a highly contagious viral infection of young chicken. The disease was first recognized 1.4 Diagnosis in Gumboro, Delaware, USA in 1962. The disease is very 1.5 Control and Prevention important to the poultry industry worldwide since the virus 2 Status of Livestock Diseases cause immunosuppression in birds leading to increased susceptibility to other diseases and negative interference 2.1 Bovine Disease with effective vaccination. Very virulent strains of IBD virus 2.1.1 Bovine Babesiosis has been spreading in Europe, Latin America, South-East 2.1.2 Bovine Brucellosis Asia, Africa and Middle East countries in recent years. 2.1.3 Foot and Mouth Disease 1.2 Epidemiology 2.1.4 Mastitis 2.2 Caprine Diseases Gumboro disease is caused by a virus of the genus Avibimavirus of the family Birnaviridae. The disease is 2.2.1 Contagious Pustular Dermatitis characterized by destruction of lymphocytes in the bursa (CPD) of fabricius and to lesser extent in other lymphoid organs. 2.3 Rabies The chicks around 3-6 weeks old show severe acute disease 2.4 Poultry Diseases with high mortality. Occurrence in younger birds is usually asymptomatic but cause permanent and severe damage 2.4.1 Fowl pox to bursa of fabricius. -

Dengue Epidemic 2017: Evidence and Lessons Learnt — Part 3 This Article, Discussed Here As the Third Deaths in 2016

WEEKLY EPIDEMIOLOGICAL REPORT A publication of the Epidemiology Unit Ministry of Health, Nutrition & Indigenous Medicine 231, de Saram Place, Colombo 01000, Sri Lanka Tele: + 94 11 2695112, Fax: +94 11 2696583, E mail: [email protected] Epidemiologist: +94 11 2681548, E mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.epid.gov.lk Vol. 45 No. 05 27th – 02th February 2018 Dengue Epidemic 2017: Evidence and Lessons Learnt — Part 3 This article, discussed here as the third deaths in 2016. of 5 parts, continues to describe the out- August 2017, saw a decline in the number break and the preventive and mitigation of cases in most of the districts, to nearly a activities carried out during the 2017 half of the numbers in July. Nevertheless, outbreak. most of dry zonal districts like Hambantota, (Continued from Previous WER) Anuradhapura, Vavuniya, Batticaloa, Trin- comalee, Badulla, and Moneragala still In June 2017, a sharp increase in the total continued to report high number of cases, cases was seen from all districts, recording an increase of 4-5 times, while Puttalam more than double the caseload in most of and Kalmunai had more than 6 times the them. Districts like Kandy, Matale, Battica- patients during this month. loa, Ampara, Kurunegala, Puttalam, Anura- dhapura, and Kalmunai recorded about 4 The downward trend continued in Septem- times the previously reported average ber where there was less than 10,000 cas- caseload. Moneragala was showing a 10 es and only 5 deaths were reported for the fold increase, although no specific areas whole month. Most of the districts had their were identified as potential outbreak areas. -

Friday, 15 January 2010, 12:23 SECRET SECTION 01

Friday, 15 January 2010, 12:23 S E C R E T SECTION 01 OF 03 COLOMBO 000032 SIPDIS DEPARTMENT FOR SCA/INSB EO 12958 DECL: 01/15/2020 TAGS PGOV, PREL, PREF, PHUM, PTER, EAID, MOPS, CE SUBJECT: SRI LANKA WAR-CRIMES ACCOUNTABILITY: THE TAMIL PERSPECTIVE REF: A. 09 COLOMBO 1180 B. COLOMBO 8 COLOMBO 00000032 001.2 OF 003 Classified By: AMBASSADOR PATRICIA A. BUTENIS. REASONS: 1.4 (B, D) ¶1. (S) SUMMARY: There have been a few tentative steps on accountability for crimes allegedly committed by Sri Lankan troops and civilian officials during the war with the LTTE. President Rajapaksa named a committee to make recommendations to him on the U.S. incidents report by April, and candidate Fonseka has discussed privately the formation of some form of “truth and reconciliation” commission. Otherwise, accountability has not been a high-profile issue -- including for Tamils in Sri Lanka. While Tamils have told us they would like to see some form of accountability, they have been pragmatic in what they can expect and have focused instead on securing greater rights and freedoms, resolving the IDP question, and improving economic prospects in the war-ravaged and former LTTE-occupied areas. Indeed, while they wanted to keep the issue alive for possible future action, Tamil politicians with whom we spoke in Colombo, Jaffna, and elsewhere said now was not time and that pushing hard on the issue would make them “vulnerable.” END SUMMARY. ACCOUNTABILITY AS A POLITICAL ISSUE ----------------------------------- ¶2. (S) Accountability for alleged crimes committed by GSL troops and officials during the war is the most difficult issue on our bilateral agenda. -

Census Codes of Administrative Units Western Province Sri Lanka

Census Codes of Administrative Units Western Province Sri Lanka Province District DS Division GN Division Name Code Name Code Name Code Name No. Code Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Sammanthranapura 005 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Mattakkuliya 010 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Modara 015 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Madampitiya 020 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Mahawatta 025 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Aluthmawatha 030 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Lunupokuna 035 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Bloemendhal 040 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kotahena East 045 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kotahena West 050 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kochchikade North 055 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Jinthupitiya 060 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Masangasweediya 065 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 New Bazaar 070 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Grandpass South 075 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Grandpass North 080 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Nawagampura 085 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Maligawatta East 090 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Khettarama 095 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Aluthkade East 100 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Aluthkade West 105 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kochchikade South 110 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Pettah 115 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Fort 120 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Galle Face 125 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Slave Island 130 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Hunupitiya 135 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Suduwella 140 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Keselwatta 145 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo -

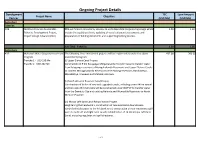

Ongoing Project Details

Ongoing Project Details Development TEC Loan Amount Project Name Objective Partner (USD Mn) (USD Mn) Agriculture Fisheries ADB Northern Province Sustainable PDA will finance consultancy services to undertake detail engineering design which 1.59 1.30 Fisheries Development Project, include the updating of cost, updating of social safeguard assessments and Project Design Advance (PDA) preparation of bidding documents and supporting bidding process. Sub Total - Fisheries 1.59 1.30 Agriculture ADB Mahaweli Water Security Investment The following three investment projects will be implemented under the above 432.00 360.00 Program investment program. Tranche 1 - USD 190 Mn (i) Upper Elahera Canal Project Tranche 2- USD 242 Mn Construction of 9 km Kaluganga-Morgahakanda Transfer Canal to transfer water from Kaluganga reservoir to Moragahakanda Reservoirs and Upper Elehera Canals to connect Moragahakanda Reservoir to the existing reservoirs; Huruluwewa, Manakattiya, Eruwewa and Mahakanadarawa. (ii) North Western Province Canal Project Construction of 96 km of new and upgraded canals, including a new 940 m tunnel and two new 25 m tall dams will be constructed under NWPCP to transfer water from the Dambulu Oya and existing Nalanda and Wemedilla Reservoirs to North Western Province. (iii) Minipe Left Bank Canal Rehabilitation Project Heightening the headwork’s, construction of new automatic downstream- controlled intake gates to the left bank canal; construction of new emergency spill weirs to both left and right bank canals; rehabilitation of 74 km Minipe Left Bank Canal, including regulator and spill structures. 1 of 24 Ongoing Project Details Development TEC Loan Amount Project Name Objective Partner (USD Mn) (USD Mn) IDA Agriculture Sector Modernization Objective is to support increasing Agricultural productivity, improving market 125.00 125.00 Project access and enhancing value addition of small holder farmers and agribusinesses in the project areas. -

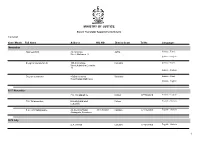

Name List of Sworn Translators in Sri Lanka

MINISTRY OF JUSTICE Sworn Translator Appointments Details 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages November Rasheed.H.M. 76,1st Cross Jaffna Sinhala - Tamil Street,Ninthavur 12 Sinhala - English Sivagnanasundaram.S. 109,4/2,Collage Colombo Sinhala - Tamil Street,Kotahena,Colombo 13 Sinhala - English Dreyton senaratna 45,Old kalmunai Baticaloa Sinhala - Tamil Road,Kalladi,Batticaloa Sinhala - English 1977 November P.M. Thilakarathne Chilaw 0777892610 Sinhala - English P.M. Thilakarathne kirimathiyana East, Chilaw English - Sinhala Lunuwilla. S.D. Cyril Sadanayake 26, De silva Road, 331490350V Kalutara 0771926906 English - Sinhala Atabagoda, Panadura 1979 July D.A. vincent Colombo 0776738956 English - Sinhala 1 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 1992 July H.M.D.A. Herath 28, Kolawatta, veyangda 391842205V Gampaha 0332233032 Sinhala - English 2000 June W.A. Somaratna 12, sanasa Square, Gampaha 0332224351 English - Sinhala Gampaha 2004 July kalaichelvi Niranjan 465/1/2, Havelock Road, Colombo English - Tamil Colombo 06 2008 May saroja indrani weeratunga 1E9 ,Jayawardanagama, colombo English - battaramulla Sinhala - 2008 September Saroja Indrani Weeratunga 1/E/9, Jayawadanagama, Colombo Sinhala - English Battaramulla 2011 July P. Maheswaran 41/B, Ammankovil Road, Kalmunai English - Sinhala Kalmunai -2 Tamil - K.O. Nanda Karunanayake 65/2, Church Road, Gampaha 0718433122 Sinhala - English Gampaha 2011 November J.D. Gunarathna "Shantha", Kalutara 0771887585 Sinhala - English Kandawatta,Mulatiyana, Agalawatta. 2 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 2012 January B.P. Eranga Nadeshani Maheshika 35, Sri madhananda 855162954V Panadura 0773188790 English - French Mawatha, Panadura 0773188790 Sinhala - 2013 Khan.C.M.S. -

Tides of Violence: Mapping the Sri Lankan Conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre

Tides of violence: mapping the Sri Lankan conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre The Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC) is an independent, non-profit legal centre based in Sydney. Established in 1982, PIAC tackles barriers to justice and fairness experienced by people who are vulnerable or facing disadvantage. We ensure basic rights are enjoyed across the community through legal assistance and strategic litigation, public policy development, communication and training. 2nd edition May 2019 Contact: Public Interest Advocacy Centre Level 5, 175 Liverpool St Sydney NSW 2000 Website: www.piac.asn.au Public Interest Advocacy Centre @PIACnews The Public Interest Advocacy Centre office is located on the land of the Gadigal of the Eora Nation. TIDES OF VIOLENCE: MAPPING THE SRI LANKAN CONFLICT FROM 1983 TO 2009 03 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 09 Background to CMAP .............................................................................................................................................09 Report overview .......................................................................................................................................................09 Key violation patterns in each time period ......................................................................................................09 24 July 1983 – 28 July 1987 .................................................................................................................................10 -

The Impacts of Small Arms Availability and Misuse in Sri Lanka

In the Shadow of a Cease-fire: The Impacts of Small Arms Availability and Misuse in Sri Lanka by Chris Smith October 2003 A publication of the Small Arms Survey Chris Smith The Small Arms Survey The Small Arms Survey is an independent research project located at the Graduate Institute of International Studies in Geneva, Switzerland. It is also linked to the Graduate Institute’s Programme for Strategic and International Security Studies. Established in 1999, the project is supported by the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, and by contributions from the Governments of Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. It collaborates with research institutes and non-governmental organizations in many countries including Brazil, Canada, Georgia, Germany, India, Israel, Jordan, Norway, the Russian Federation, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Sweden, Thailand, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The Small Arms Survey occasional paper series presents new and substantial research findings by project staff and commissioned researchers on data, methodological, and conceptual issues related to small arms, or detailed country and regional case studies. The series is published periodically and is available in hard copy and on the project’s web site. Small Arms Survey Phone: + 41 22 908 5777 Graduate Institute of International Studies Fax: + 41 22 732 2738 47 Avenue Blanc Email: [email protected] 1202 Geneva Web site: http://www.smallarmssurvey.org Switzerland ii Occasional Papers No. 1 Re-Armament in Sierra Leone: One Year After the Lomé Peace Agreement, by Eric Berman, December 2000 No. 2 Removing Small Arms from Society: A Review of Weapons Collection and Destruction Programmes, by Sami Faltas, Glenn McDonald, and Camilla Waszink, July 2001 No. -

Jaffna's Media in the Grip of Terror

Fact-finding report by the International Press Freedom Mission to Sri Lanka Jaffna’s media in the grip of terror August 2007 Since fighting resumed in 2006 between the government and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), the Tamil-populated Jaffna peninsula has become a nightmare for journalists, human rights activists and the civilian population in general. Murders, kidnappings, threats and censorship have made Jaffna one of the world’s most dangerous places for journalists to work. At least seven media workers, including two journalists, have been killed there since May 2006. One journalist is missing and at least three media outlets have been physically attacked. Dozens of journalists have fled the area or abandoned the profession. None of these incidents has been seriously investigated despite government promises and the existence of suspects. Representatives of Reporters Without Borders and International Media Support visited Jaffna on 20 and 21 June as part of an international press freedom fact-finding mission to Sri Lanka. They met Tamil journalists, military officials, civil society figures and the members of the national Human Rights Commission (HRC). This report is also based on the day-by-day press freedom monitoring done by Reporters Without Borders and other organisations in the international mission. For security reasons, the names of most of the journalists and other people interviewed are not cited here. Since the attack on 2 May last year on the offices of the Jaffna district’s most popular daily paper, Uthayan, local journalists have lived and worked in fear. One paper shut down after its editor was murdered and only three dailies are now published. -

Impunity for Killing of 27 Inmates of the Welikada Prison Colombo in November 2012 (20Th June 2016)

Committee For Protecting Rights Of Prisoners 17, Berkka Lane, Colombo 2, Sri Lanka Tel: +94-112-430621/ +94-71-4453890 / +94-772817164 Fax: +94-11-2305963 Email: [email protected] Impunity for killing of 27 inmates of the Welikada Prison Colombo in November 2012 (20th June 2016) 1. Introduction & summary In November 2012, 27 inmates at the Welikada Prison, in Colombo, Sri Lanka, were reported as killed by the Army and the Special Task Force (STF) following what was reported as a search operation leading to a riot. 43 persons have also been reported as injured. Based on testimony of eyewitnesses, the Commissioner General of Prisons was seen inside the prison in the morning of 10th November (after midnight on 9th November) and thus, it is believed that he is aware of names of the Army officers present inside the prison during the massacre. According to two available Inquirer‟s Certificates of Deaths, cause of death is due to shooting. However, one indicated that shooting was from afar, while eyewitnesses affirmed that all victims were shot at close range. There were various investigations announced by the present and previous governments as well as the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka. But none of the reports have been published. Todate, no individual has been indicted. After the new government came into power on 8th January 2015, families of those killed witnesses and concerned lawyers and activists raised the profile of the campaign, with protests and press conferences demanding the publication of reports, relief for victim‟s families and justice. Witnesses and campaigners gave interviews to media and made fresh police complaints and appeals to the President and the Prime Minister.