General Dentistry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dantal College Inner Pages Vol-7 Issue-2.Cdr

JADCH ISSN 0976-2256 E-ISSN: 2249-6653 The journal is indexed with ‘Indian Science Abstract’ (ISA) (Published by National Science Library), www.ebscohost.com, www.indianjournals.com JADCH is available (full text) online: Website- www.adc.org.in/html/viewJournal.php This journal is an official publication of Ahmedabad Dental College and Hospital, published bi-annually in the month of March and September. The journal is printed on ACID FREE paper. Editor - in - Chief Dr. Darshana Shah Co - Editor Dr. Harsh Shah Editorial Board: DENTISTRY TODAY... The last decade has witnessed the most rapid advances in Dr. Mihir Shah the field of oral andmaxillofacial radiology. With the advent Dr. Vijay Bhaskar and acceptance of CBCT (3D) imaging invarious fields of dentistry; the dentists today are taking more accurate and Dr. Monali Chalishazar informeddecisions regarding complicated patients and their treatment planning. However, today’spatients demand more Dr. A. R. Chaudhary and more comfort and less intraoperative time; even if it comes Dr. Neha Vyas athigher treatment cost. With ever increasing patient affordability as well as expectations, the least should be left to Dr. Sonali Mahadevia dental surgeon’s imaginations. Dr. Shraddha Chokshi Welcome to the era of 3D printing; the next step after 3D Dr. Bhavin Dudhia imaging. With 3D printedmodels on hand, the dentist can actually perform a mock surgery on a model, whichrepresents Dr. Mahadev Desai the patient accurately in three dimensions; and hence reduces the intraoperative time. 3D printing, also called additive Dr. Darshit Dalal manufacturing; creates a physicalobject by layer by layer deposition of material. This technology can be helpful inpreparing surgical stents for implant placements, models for oral and maxillofacialtrauma and pathology cases, prosthetic rehabilitation cases, complicated endodontic casesas well as for orthodontic appliances. -

Endodontic Management of Central Incisor Associated with Large Periapical Lesion and Fused Supernumerary Root: a Conservative Approach

Restor Dent Endod. 2018 Nov;43(4):e44 https://doi.org/10.5395/rde.2018.43.e44 pISSN 2234-7658·eISSN 2234-7666 Case Report Endodontic management of central incisor associated with large periapical lesion and fused supernumerary root: a conservative approach Gautam P. Badole ,1* Pratima R. Shenoi ,1 Ameya Parlikar 2 1Department of Conservative Dentistry & Endodontics, VSPM's Dental College & Research Center, Nagpur, MH, India 2Department of Conservative Dentistry & Endodontics, Rangoonwala Dental College and Research Center, Pune, MH, India Received: Mar 19, 2018 ABSTRACT Accepted: Aug 21, 2018 Badole GP, Shenoi PR, Parlikar A Fusion and gemination are developmental anomalies of teeth that may require endodontic treatment. Fusion may cause various clinical problems related to esthetics, tooth spacing, and *Correspondence to other periodontal complications. Additional diagnostic tools are required for the diagnosis and Gautam P. Badole, MDS Reader, Department of Conservative Dentistry the treatment planning of fused tooth. The present case report describes a case of unilateral & Endodontics, VSPM's Dental College & fusion of a supernumerary root to an upper permanent central incisor with large periapical Research Center, Hingna Road, Digdoh Hills, lesion in which a conservative approach was used without extraction of supernumerary tooth Nagpur, MH 440019, India. and obturated with mineral trioxide aggregate to reach a favorable outcome. E-mail: [email protected] Keywords: Cone-beam computed tomography; Fused teeth; Mineral trioxide aggregate; Copyright © 2018. The Korean Academy of Supernumerary tooth Conservative Dentistry This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (https:// INTRODUCTION creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any Developmental tooth anomalies are deviation from the normal appearance in color, medium, provided the original work is properly shape, size and number of teeth. -

THE YOUNG and the OLD: NORMAL and VARIATIONS from NORMAL Judy Rochette DVM, FAVD, Dipl AVDC

THE YOUNG AND THE OLD: NORMAL AND VARIATIONS FROM NORMAL Judy Rochette DVM, FAVD, Dipl AVDC The majority of notable findings in the oral cavity of the young pet are related to its formation and development, as well as the development and eruption of teeth, whereas senior pet variations reflect the gradual aging of the dental hard tissues and their supporting structures. The head, face, and oral cavity are some of the first structures to manifest in the developing embryo. The upper face forms from the neural tube while the lower face forms from branchial arches. The oral mucosa and upper alimentary tract form from the ectodermal layers. The mesenchymal layer provides the cells which will become subcutaneous tissues and the bone and supporting apparatus for the teeth. The teeth themselves are both ectodermal and mesodermal in origin. Any phenotypic variation from the "wild type" of head, or any genetic anomaly which affects the ectoderm or mesodermal tissues will likely have an effect on the oral cavity. Some of these anomalies have been intentionally introduced to create new "breeds". BRACHYCEPHALIC SYNDROME Brachycephalic syndrome is a set of dysfunctional anatomical airway variations familiar to veterinarians who deal with Bulldogs, Pugs and Boston Terriers but this syndrome is also a problem in Persian, Himalayan and Burmese cats. Stenotic nares, an elongated soft palate, hypoplastic trachea and everted laryngeal saccules can all inhibit respiration. Mouth breathing, stertor, exercise intolerance and collapse after exercise can be seen. Early surgical intervention to open the nares and shorten the palate will often arrest the development of everted saccules, lower respiratory tract inflammation and cardiac stress. -

Rare Anatomical Variations of Third Molars: Two Cases Reported

Case Report DOI: 10.18231/2278-3784.2018.0021 Rare anatomical variations of third molars: Two cases reported Ashvini Vadane1,*, Hassaan Kazi2, Amit Sangle3 1Senior Lecturer, 2PG Student, 3Professor, Dept. of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, M.A. Rangoonwala College of Dental Sciences and Research Centre, Pune, Maharashtra, India *Corresponding Author: Ashvini Vadane Email: [email protected] Abstract The size of tooth and appearance are being easily noticed. The crown of the tooth is being affected by the majority of pathological variations in the morphology of tooth. Variations in the morphology of tooth have been a topic of interest to dentists since long time.1 We report here, two rare cases of four-rooted maxillary third molar and three-rooted mandibular third molar. Extraction of such type of teeth is considered to be a difficult task. We had managed extraction of these teeth with absence of any postoperative complications and teeth were being extracted in-toto. Keywords: Maxillary third molar, Mandibular third molar, Morphological variations, Three rooted molar, Four rooted molar. Introduction of Dental Sciences and Research Centre, Pune. Although In this article, we are reporting two rare cases .In the first these teeth were having abnormal and difficult root patterns, case, the maxillary third molar is having four roots and in the we had extracted these teeth in-toto with no postoperative second case, mandibular third molar is having three roots. complications. Fig. 1 shows extracted maxillary third molar Both these incidences are very rare. Extraction of these teeth tooth which is having four roots whereas Fig. 2 indicates is considered to be difficult because of abnormal root extracted mandibular third molar tooth which is having three patterns. -

What the General Dental Practitioner Should Know About Cone Beam Com- Puted Tomograph Technology

What the general dental practitioner should know about cone beam com- puted tomograph technology Magdalena Marinescu Gava1 1 D.D.S. Pirkanmaa Hospital District, Regional Imaging Centre, Tampere, Finland. Abstract Ionising radiation is used in health care for the diagnosis of diseases, for prevention (such as screening for breast can- cer) and for treatment (radiotherapy). The aim of radiation protection is to ensure that radiation is used safely and that exposure of the patient is kept to a minimum. The principles of radiation protection are based on the recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP). To be acceptable, the use of ionising radiation must be justified, optimal, and limited. Dental radiography has been used since the beginning of radiology and now accounts for nearly one-third of the total number of radiological examinations in the European Union. Pantomography is widely used because in one exposure it records the jaws, temporomandibular joints, maxillary sinuses, and dentition. However, when this technique is used, superimposition of structures in the dentomaxillofacial area has been a limitation in mak- ing reliable diagnoses due to the complexity of the anatomy in this region. These shortcomings have led to development of three-dimensional techniques. One of these techniques, cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), is now available for use in everyday general practice. The aim of this paper is to present CBCT’s advantages and limitations when com- pared with alternative imaging techniques and to stress how it may be used safely in general dental practice. Key Words: Medical Subjects, Radiation Protection, Dentistry, Cone-Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) Introduction the complicated human anatomy. -

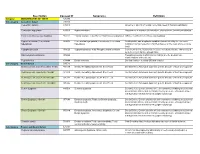

Description Concept ID Synonyms Definition

Description Concept ID Synonyms Definition Category ABNORMALITIES OF TEETH 426390 Subcategory Cementum Defect 399115 Cementum aplasia 346218 Absence or paucity of cellular cementum (seen in hypophosphatasia) Cementum hypoplasia 180000 Hypocementosis Disturbance in structure of cementum, often seen in Juvenile periodontitis Florid cemento-osseous dysplasia 958771 Familial multiple cementoma; Florid osseous dysplasia Diffuse, multifocal cementosseous dysplasia Hypercementosis (Cementation 901056 Cementation hyperplasia; Cementosis; Cementum An idiopathic, non-neoplastic condition characterized by the excessive hyperplasia) hyperplasia buildup of normal cementum (calcified tissue) on the roots of one or more teeth Hypophosphatasia 976620 Hypophosphatasia mild; Phosphoethanol-aminuria Cementum defect; Autosomal recessive hereditary disease characterized by deficiency of alkaline phosphatase Odontohypophosphatasia 976622 Hypophosphatasia in which dental findings are the predominant manifestations of the disease Pulp sclerosis 179199 Dentin sclerosis Dentinal reaction to aging OR mild irritation Subcategory Dentin Defect 515523 Dentinogenesis imperfecta (Shell Teeth) 856459 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; Autosomal dominant genetic disorder of tooth development Dentinogenesis Imperfecta - Shield I 977473 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; Autosomal dominant genetic disorder of tooth development Dentinogenesis Imperfecta - Shield II 976722 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; -

Dental and Temporomandibular Joint Pathology of the Walrus (Odobenus Rosmarus)

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works Title Dental and Temporomandibular Joint Pathology of the Walrus (Odobenus rosmarus). Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/05z8k86z Journal Journal of comparative pathology, 155(2-3) ISSN 0021-9975 Authors Winer, JN Arzi, B Leale, DM et al. Publication Date 2016-08-13 DOI 10.1016/j.jcpa.2016.07.005 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California J. Comp. Path. 2016, Vol. -,1e12 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect www.elsevier.com/locate/jcpa DISEASE IN WILDLIFE OR EXOTIC SPECIES Dental and Temporomandibular Joint Pathology of the Walrus (Odobenus rosmarus) J. N. Winer*, B. Arzi†, D. M. Leale†,P.H.Kass‡ and F. J. M. Verstraete† *William R. Pritchard Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital, † Department of Surgical and Radiological Sciences and ‡ Department of Population Health and Reproduction, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis, CA, USA Summary Maxillae and/or mandibles from 76 walruses (Odobenus rosmarus) were examined macroscopically according to predefined criteria. The museum specimens were acquired between 1932 and 2014. Forty-five specimens (59.2%) were from male animals, 29 (38.2%) from female animals and two (2.6%) from animals of unknown sex, with 58 adults (76.3%) and 18 young adults (23.7%) included in this study. The number of teeth available for examination was 830 (33.6%); 18.5% of teeth were absent artefactually, 3.3% were deemed to be absent due to acquired tooth loss and 44.5% were absent congenitally. The theoretical complete dental formula was confirmed to be I 3/3, C 1/1, P 4/3, M 2/2, while the most probable dental formula is I 1/0, C 1/1, P 3/3, M 0/0; none of the specimens in this study possessed a full complement of theoretically possible teeth. -

Prevalence and Distribution of Dental Anomalies in a Paediatric

Prevalence and distribution of dental V.P. Wagner1, T. Arrué2, E. Hilgert2, N. A. Arús3, H. L. D. da Silveira3, anomalies in a paediatric M. D. Martins4, J. A. Rodrigues2 1Academic Unit of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, School of Clinical Dentistry - population based on University of Sheffield, UK 2Paediatric Dentistry Division, School of Dentistry, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil panoramic radiographs 3Oral Radiology Division, School of Dentistry, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil 4Oral Pathology Division, School of Dentistry, analysis Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil DOI 10.23804/ejpd.2020.21.04.7 e-mail: [email protected] Abstract considered to be the main aetiological factors. Variations in the dental morphology and structure, for example, typically result from disturbances during embryological development. Aim To evaluate the frequency and distribution of dental Nevertheless, environmental factors that occur during the anomalies (DA) in a paediatric population. prenatal and postnatal development period can also trigger the Material and methods Panoramic digital radiographs of children between 6 and 12 years old performed at a reference centre development of DA, particularly positional abnormalities or for radiographic exams were accessed. Two calibrated examiners disorders in the eruption chronology [Vani et al., 2016; Laganà evaluated the radiographs. The association between variables and et al., 2017]. The identification of DA is important once they outcomes was assessed using non-parametric tests. The significance can cause disturbances such as malocclusion, increased level was set at 5%. susceptibility to caries and aesthetic issues [Mukhopadhyay and Results Five hundred and twelve individuals were included Mitra, 2014]. -

Indian Dental Association Contents

INDIAN DENTAL ASSOCIATION CONTENTS Dr. Siddharth Bansal Prosthetic Rehabilitation of Maxillary Flabby Dr. Meena A. Aras Dr. Vidya Chitre Ridge Using Liquid Supported Denture: Dr. Rajiv Kumar Gupta Dr. Anil K. Jain A Case Report Dr. D Kabi Abstract : Flabby ridges commonly occur in edentulous patients. Inadequate retention and stability of a complete denture are the often encountered problems in these patients. A liquid supported denture due to its flexible tissue surface allows better distribution of stress and hence provides an alternate treatment modality in such cases. This case report presents the use of a liquid supported denture in a patient with completely edentulous maxillary arch with flabby tissue in anterior region opposing a completely edentulous mandibular arch. Furthermore, Esthetics was improved by characterizing the dentures to match with patient lip color. Running Title: Liquid Supported Denture Key Words: Liquid Supported Denture, Flabby ridge, Glycerin, Polyethylene sheet Corresponding Author: Dr. Siddharth Bansal, Senior Lecturer, Department of Prosthodontics, I.T.S Centre for Dental Studies and Research, Delhi-Meerut Road, Murad Nagar, U.P., India Corresponding Author's Mailing Address: 346, Street no. 11, Near Jharkhandi Mandir, Bhola Nath Nagar, Shahdara, Delhi 110032 Corresponding Author's email: [email protected] Mobile phone no. to which sms / call with regards to the article can be sent: +91-9643084022 Dr. Meena A. Aras, Professor and Head, Department of Prosthodontics, Goa Dental College and Hospital, Bambolim, Goa, India. Dr. Vidya Chitre, Professor, Department of Prosthodontics, Goa Dental College and Hospital, Bambolim, Goa, India. Dr. Rajiv Kumar Gupta, Assistant Professor, Dental Department, VMMC & Safdarjang Hospital, New Delhi-110029. -

II BDS Curriculum

CURRICULUM FOR II BDS COURSE PROPOSED FOR SHRI DHARMASTHALA MANJUNATHESHWARA UNIVERSITY 1 GENERAL PATHOLOGY 1. Aims and Objectives: Student must be competent to apply and correlate the study of disease processes resulting in morphological and functional alteration in cells, tissues and organs to study of Pathology and Dentistry practice. O BJECTIVES: Enabling the student a. To demonstrate and apply basic facts, concepts and theories in the field of Pathology. b. To recognize and analyze pathological changes at macroscopic and microscopy levels and explain their observations in terms of disease processes. c. To integrate knowledge from the basic sciences, clinical medicine and dentistry in the study of Pathology. d. To demonstrate understanding of the capabilities and limitations of morphological Pathology in its contribution to medicine, dentistry and biological research. 2. Teaching hours: Lecture Hours – 55 hrs. Practical Hours – 55 hrs. Total – 110 hrs. 3. Teaching schedule for Theory -55 hrs. Teaching SL. Learning Content Distribution Topic hours No. Must know Desirable to know 1 Introduction to pathology - Techniques Evolution of 02 evolution of modern used in the modern pathology, subdivisions in study of pathology pathology, techniques used in pathology and the study of pathology and terms used in pathology. terms used in Normal cell structure pathology. Cell structure. 2 2 Disturbances of metabolism Intra cellular 03 of cells- accumulations - Intra cellular accumulations, Fatty change Fatty change, Hyaline change, Pathologic Accumulation of lipids, proteins and glycogen. calcification Cellular swelling, Disorders of pigmentation and pathologic calcification. 3 Cell injury and cell death - Necrosis - 04 Causes, Types, mechanism, definitions, types intracellular changes, of necrosis with morphology with examples, examples Cell death. -

What Is Your Diagnosis and Treatment Plan?

1 Verstraete FJ, Kass PH, Terpak CH. Diagnostic value of full-mouth Radiography in dogs. Am J Vet Res 1998:59(6):686-691. Verstraete FJ, Kass PH, Terpak CH. Diagnostic value of full-mouth Radiography in cats. Am J Vet Res 1998:59(6):692-695. Normal periodontal anatomy PDL PDL Apex * Supernumerary root * * Root canal Dentin Dentin * Crown Enamel Enamel * Alveolar bone 2 Stages of Periodontal Disease • Stage I: Gingivitis - No Attachment Loss (AL) • Stage II: Early PD - Up to 25% AL • Stage III: Moderate PD - 25%-50% AL • Stage IV: Severe PD - greater than 50% AL 3 Note mild plaque & dental calculus & associated gingivitis in 2-year-old patient. Note periodontal pocket on mesial aspect of mesial root of mandibular 2nd molar. Less than 25% of the total periodontal attachment of both roots of tooth has been lost resulting in Stage II periodontal disease. 4 Note furcation exposure of premolar tooth. Radiograph demonstrates 25-50% of attachment has been lost resulting in Stage III periodontal disease. Bone loss around mesial roots of mandibular first molars 5 6 Potential Sequelae Associated with Failure to Treat Teeth Affected with Endodontic Disease Discolored tooth Abscess formation Cutaneous and mucosal fistula formation Chronic rhinitis Ocular signs This radiograph demonstrates periapical lysis, apical lysis, and an asymmetric and wide root canal 7 Apical lysis/resorption in a cat secondary to chronic pulpal exposure Resorptive Lesions •Odontoclastic attack on teeth •No etiology has been confirmed yet, so treatment is aimed at minimizing -

Radix Entomolaris)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences (2014) 9(1), 81–84 Taibah University Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences www.sciencedirect.com Case Report Clinical management of amandibular first molar with supernumerary distal root (radix entomolaris) Mothanna Alrahabi, PhD Department of Restorative Dentistry, College of Dentistry, Taibah University, Medina, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Received 14 August 2013; revised 28 October 2013; accepted 1 November 2013 ﺍﻟﻤﻠﺨﺺ Keywords: Anatomy; Mandibular; Molar; Radix entomolares; Root canal ﻳﻌﺘﺒﺮ ﺍﻟﺠﺬﺭ ﺍﻟﺮﺣﻮﻱ ﺍﻟﺰﺍﺋﺪ ﻓﻲ ﺍﻟﺠﻬﺔ ﺍﻟﻠﺴﺎﻧﻴﺔ ﺍﻟﻘﺎﺻﻴﺔ ﺃﺣﺪ ﺍﻻﺧﺘﻼﻓﺎﺕ ﺍﻟﺘﺸﺮﻳﺤﻴﺔ ﻓﻲ ﺍﻟﺮﺣﻰ ﺍﻷﻭﻟﻰ ﺑﺎﻟﻔﻚ ﺍﻟﺴﻔﻠﻲ، ﻭﻳﺤﺘﺎﺝ ﻫﺬﺍ ﺍﻻﺧﺘﻼﻑ ﺍﻟﺘﺸﺮﻳﺤﻲ ﺇﻟﻰ ﻋﻨﺎﻳﺔ ﺧﺎﺻﺔ Ó 2014 Taibah University. Production and hosting by Elsevier ﻭﺫﻟﻚ ﻟﻠﺤﻔﺎﻅ ﻋﻠﻰ ﻣﺴﺘﻮﻯ ﻧﺠﺎﺡ ﻋﺎﻝ ﻟﻤﻌﺎﻟﺠﺔ ﺃﻧﻔﺎﻕ ﺟﺬﻭﺭ ﺍﻷﺳﻨﺎﻥ. ﺗﺼﻒ ﻫﺬﻩ .Ltd. All rights reserved ﺍﻟﻤﻘﺎﻟﺔ ﺍﻹﺟﺮﺍﺀﺍﺕ ﺍﻟﻌﻼﺟﻴﺔ ﻟﻠﺮﺣﻰ ﺍﻷﻭﻟﻰ ﺑﺎﻟﻔﻚ ﺍﻟﺴﻔﻠﻲ ﺑﺜﻼﺛﺔ ﺟﺬﻭﺭ (ﺟﺬﺭ ﺇﻧﺴﻲ ﻭﺟﺬﺭﺍﻥ ﻗﺎﺻﻴﺎﻥ) ﻭﺃﺭﺑﻌﺔ ﻗﻨﻮﺍﺕ (ﻗﻨﺎﺗﺎﻥ ﻓﻲ ﺍﻟﺠﺬﺭ ﺍﻹﻧﺴﻲ ﻭﻗﻨﺎﺓ ﻓﻲ ﺍﻟﺠﺬﺭ ﺍﻟﻠﺴﺎﻧﻲ ﺍﻟﻘﺎﺻﻲ ﻭﻗﻨﺎﺓ ﻓﻲ ﺍﻟﺠﺬﺭ ﺍﻟﺸﺪﻗﻲ ﺍﻟﻘﺎﺻﻲ) ﻳﻈﻬﺮ ﺗﻘﺮﻳﺮ ﻫﺬﻩ ﺍﻟﺤﺎﻟﺔ ﺃﻫﻤﻴﺔ Introduction ﻣﻌﺮﻓﺔ ﺗﺸﺮﻳﺢ ﺍﺍﻟﻘﻨﻮﺍﺕ ﺍﻟﺠﺬﺭﻳﺔ ﻭﺃﻫﻤﻴﺔ ﺍﻟﺘﺼﻮﻳﺮ ﺍﻟﺸﻌﺎﻋﻲ ﻗﺒﻞ ﻣﻌﺎﻟﺠﺔ ﺍﻟﺠﺬﻭﺭ ﺟﺮﺍﺣﻴﺎ. Thorough knowledge of root canal anatomy, both normal and ﺍﻟﻜﻠﻤﺎﺕ ﺍﻟﻤﻔﺘﺎﺡ: ﺍﻟﺠﺬﺭ ﺍﻟﺮﺣﻮﻱ ﺍﻟﺰﺍﺋﺪ; ﺍﻟﺮﺣﻰ; ﺍﻟﻔﻚ ﺍﻟﺴﻔﻠﻲ; ﻗﻨﺎﺓ ﺍﻟﺠﺬﺭ; ﻋﻠﻢ ﺍﻟﺘﺸﺮﻳﺢ abnormal, is essential for successful root canal treatment.1 The Abstract mandibular first molar typically has two well-defined roots: a mesial root characterised by a flattened mesiodistal surface and widened buccolingual surface, and a distal root, which is Radix entomolares, a supernumerary root on a mandibular 2 molar, located distolingually, is an anatomical variation of usually straight with a wide oval canal or two round canals.