Issues in Dentistry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Periodontal Approach of Impacted and Retained Maxillary Anterior Teeth

DOI: 10.1051/odfen/2018053 J Dentofacial Anom Orthod 2018;21:204 © The authors Periodontal approach of impacted and retained maxillary anterior teeth N. Henner1, M. Pignoly*2, A. Antezack*3, V. Monnet-Corti*4 1 Former University Hospital Assistant Periodontology – Private Practice, 30000 Nîmes 2 University Hospital Assistant Periodontology – Private Practice, 13012 Marseille 3 Oral Medicine Resident, 13005 Marseille 4. University Professor. Hospital practitioner. President of the French Society of Periodontology and Oral Implantology * Public Assistant for Marseille Hospitals (Timone-AP-HM Hospital, Odontology Department, 264 rue Saint-Pierre, 13385 Marseille) – Faculty of Odontology, Aix-Marseille University (27 boulevard Jean-Moulin, 13385 Marseille) ABSTRACT Treatment of the impacted and retained teeth is a multidisciplinary approach involving close coopera- tion between periodontist and orthodontist. Clinical and radiographic examination leading subsequently to diagnosis, remain the most important prerequisites permitting appropriate treatment. Several surgical techniques are available to uncover impacted/retained tooth according to their position within the osseous and dental environment. Moreover, to access to the tooth and to bond an orthodontic anchorage, the surgical techniques used during the surgical exposure must preserve the periodontium integrity. These surgical techniques are based on tissue manipulations derived from periodontal plastic surgery, permitting to establish and main- tain long-term periodontal health. KEYWORDS Mucogingival surgery, periodontal plastic surgery, impacted tooth, retained tooth, surgical exposure INTRODUCTION A tooth is considered as impacted when it eruption 18 months after the usual date of has not erupted after the physiological date eruption, when the root apices are edified and its follicular sac does not connect with and closed. -

Dantal College Inner Pages Vol-7 Issue-2.Cdr

JADCH ISSN 0976-2256 E-ISSN: 2249-6653 The journal is indexed with ‘Indian Science Abstract’ (ISA) (Published by National Science Library), www.ebscohost.com, www.indianjournals.com JADCH is available (full text) online: Website- www.adc.org.in/html/viewJournal.php This journal is an official publication of Ahmedabad Dental College and Hospital, published bi-annually in the month of March and September. The journal is printed on ACID FREE paper. Editor - in - Chief Dr. Darshana Shah Co - Editor Dr. Harsh Shah Editorial Board: DENTISTRY TODAY... The last decade has witnessed the most rapid advances in Dr. Mihir Shah the field of oral andmaxillofacial radiology. With the advent Dr. Vijay Bhaskar and acceptance of CBCT (3D) imaging invarious fields of dentistry; the dentists today are taking more accurate and Dr. Monali Chalishazar informeddecisions regarding complicated patients and their treatment planning. However, today’spatients demand more Dr. A. R. Chaudhary and more comfort and less intraoperative time; even if it comes Dr. Neha Vyas athigher treatment cost. With ever increasing patient affordability as well as expectations, the least should be left to Dr. Sonali Mahadevia dental surgeon’s imaginations. Dr. Shraddha Chokshi Welcome to the era of 3D printing; the next step after 3D Dr. Bhavin Dudhia imaging. With 3D printedmodels on hand, the dentist can actually perform a mock surgery on a model, whichrepresents Dr. Mahadev Desai the patient accurately in three dimensions; and hence reduces the intraoperative time. 3D printing, also called additive Dr. Darshit Dalal manufacturing; creates a physicalobject by layer by layer deposition of material. This technology can be helpful inpreparing surgical stents for implant placements, models for oral and maxillofacialtrauma and pathology cases, prosthetic rehabilitation cases, complicated endodontic casesas well as for orthodontic appliances. -

General Dentistry

QUINTESSENCE INTERNATIONAL GENERAL DENTISTRY Adrian Kasaj Root resective procedures vs implant therapy in the management of furcation-involved molars Adrian Kasaj, PD Dr med dent1 Therapeutic decision making and successful treatment of fur- ment, the clinician is increasingly confronted with the dilemma cation-involved molars has been a challenge for many clin- of whether to treat a furcated molar by traditional root resec- icians. Over recent decades, several techniques have been tive techniques or to extract the tooth and replace it with a advocated in the treatment of furcated molar teeth, including dental implant. This article reviews the outcomes of root resec- nonsurgical periodontal therapy, regenerative therapy, and tive therapy for the management of furcation-involved multi- resective surgical procedures. Today, root resection is consid- rooted teeth and discusses treatment alternatives including ered a relevant treatment modality in the management of fur- implant therapy. Treatment guidelines for root resective thera- cation-involved multirooted molars. However, root resective py, along with advantages and limitations, are presented to procedures are very technique-sensitive and require a high help the clinician in the decision-making process. level of periodontal, endodontic, and restorative expertise. (Quintessence Int 2014;45:521–529; doi: 10.3290/j.qi.a31806) Given the high documented success rates of implant treat- Key words: furcation involvement, furcations, molar, periodontal disease, root resection The management and long-term retention of furcated teeth without furcation involvement.3,4 Even with a molar teeth has always been a challenge for clinicians. surgical approach selected to improve access for root Furcation involvement is defined as interradicular bone surface debridement, complete calculus removal in the resorption and attachment loss in multirooted teeth furcation area is rare.5 The compromised results in fur- caused by periodontal disease. -

Endodontic Management of Central Incisor Associated with Large Periapical Lesion and Fused Supernumerary Root: a Conservative Approach

Restor Dent Endod. 2018 Nov;43(4):e44 https://doi.org/10.5395/rde.2018.43.e44 pISSN 2234-7658·eISSN 2234-7666 Case Report Endodontic management of central incisor associated with large periapical lesion and fused supernumerary root: a conservative approach Gautam P. Badole ,1* Pratima R. Shenoi ,1 Ameya Parlikar 2 1Department of Conservative Dentistry & Endodontics, VSPM's Dental College & Research Center, Nagpur, MH, India 2Department of Conservative Dentistry & Endodontics, Rangoonwala Dental College and Research Center, Pune, MH, India Received: Mar 19, 2018 ABSTRACT Accepted: Aug 21, 2018 Badole GP, Shenoi PR, Parlikar A Fusion and gemination are developmental anomalies of teeth that may require endodontic treatment. Fusion may cause various clinical problems related to esthetics, tooth spacing, and *Correspondence to other periodontal complications. Additional diagnostic tools are required for the diagnosis and Gautam P. Badole, MDS Reader, Department of Conservative Dentistry the treatment planning of fused tooth. The present case report describes a case of unilateral & Endodontics, VSPM's Dental College & fusion of a supernumerary root to an upper permanent central incisor with large periapical Research Center, Hingna Road, Digdoh Hills, lesion in which a conservative approach was used without extraction of supernumerary tooth Nagpur, MH 440019, India. and obturated with mineral trioxide aggregate to reach a favorable outcome. E-mail: [email protected] Keywords: Cone-beam computed tomography; Fused teeth; Mineral trioxide aggregate; Copyright © 2018. The Korean Academy of Supernumerary tooth Conservative Dentistry This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (https:// INTRODUCTION creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any Developmental tooth anomalies are deviation from the normal appearance in color, medium, provided the original work is properly shape, size and number of teeth. -

PERIODONTAL DISEASE Restoring the Health of Your Teeth and Gums

502 Jefferson Highway N. Champlin, MN 55316 763 427-1311 www.moffittrestorativedentistry.com TREATING PERIODONTAL DISEASE Restoring the Health of Your Teeth and Gums YOUR GUMS NEED SPECIAL CARE Today, infection of the gums and supportive tissues surrounding the teeth (periodontal disease) can be controlled and in some cases even reversed. A variety of effective periodontal therapies are available to treat this disease, whether it has developed slowly or quickly. That’s why Dr. Moffitt may refer you to a periodontist—a specialist who can give your gums and teeth the special care they require. Working as part of your treatment team, your periodontist can help restore your mouth to a healthier condition and improve the chances of preserving your teeth. Your Gums Are in Trouble There are many telltale signs of periodontal disease: swollen, painful, or bleeding gums, bad breath, and loose or sensitive teeth. But gums don’t always let you know they’re in trouble, even in the late stages of disease. Bacterial infection may be silently and progressively destroying the soft tissues and bone that support your teeth. Early diagnosis of periodontal disease, prompt treatment, and regular checkups bring the best results. Making a Lifelong Commitment Periodontal disease is a serious and often ongoing condition, so it takes a committed, on going treatment program to control it effectively. After a thorough evaluation, your periodontist will recommend the best course of professional treatment. Whether this means nonsurgical or surgical treatment, it always includes home care. The periodontal therapy you get in the office takes care of the infection you have now, and sets the stage for maintaining control. -

Periodontal Surgery in Furcation-Involved Maxillary Molars Revisited—An Introduction of Guidelines for Comprehensive Treatment

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by RERO DOC Digital Library Clin Oral Invest (2011) 15:9–20 DOI 10.1007/s00784-010-0431-9 REVIEW Periodontal surgery in furcation-involved maxillary molars revisited—an introduction of guidelines for comprehensive treatment Clemens Walter & Roland Weiger & Nicola Ursula Zitzmann Received: 1 November 2009 /Accepted: 1 June 2010 /Published online: 23 June 2010 # Springer-Verlag 2010 Abstract Maxillary molars with interradicular loss of overview, including what constitutes accurate diagnosis and periodontal tissue have an increased risk of additional what indications there are for the different surgical attachment loss with an impaired long-term prognosis. periodontal treatment options. Since accurate clinical analysis of furcation involvement is not feasible due to limited access, morphological variations Keywords Furcation involvement . Furcation surgery. and measurement errors, additional diagnostics, e.g., with Diagnosis . Decision making . 3D imaging cone-beam computed tomography, may be required. Surgi- cal treatment options have graduated from a less invasive Abbreviations and acronyms approach, i.e., keeping as much periodontal attachment as FI Furcation involvement possible, to a more invasive approach: (1) open flap PPD Probing pocket depth debridement with/without gingivectomy or apically reposi- PAL Probing attachment level tioned flap and/or tunnelling; (2) root separation; (3) Sc&Rp Scaling and root planning amputation/trisection of a root (with/without root separation RCT Root canal treatment or tunnel preparation); (4) amputation/trisection of two SPT Supportive periodontal treatment roots; and (5) extraction of the entire tooth. Tunnelling is FDP Fixed dental prosthesis indicated when the degree of root separation allows for RDP Removable dental prosthesis opening of the interradicular region. -

THE YOUNG and the OLD: NORMAL and VARIATIONS from NORMAL Judy Rochette DVM, FAVD, Dipl AVDC

THE YOUNG AND THE OLD: NORMAL AND VARIATIONS FROM NORMAL Judy Rochette DVM, FAVD, Dipl AVDC The majority of notable findings in the oral cavity of the young pet are related to its formation and development, as well as the development and eruption of teeth, whereas senior pet variations reflect the gradual aging of the dental hard tissues and their supporting structures. The head, face, and oral cavity are some of the first structures to manifest in the developing embryo. The upper face forms from the neural tube while the lower face forms from branchial arches. The oral mucosa and upper alimentary tract form from the ectodermal layers. The mesenchymal layer provides the cells which will become subcutaneous tissues and the bone and supporting apparatus for the teeth. The teeth themselves are both ectodermal and mesodermal in origin. Any phenotypic variation from the "wild type" of head, or any genetic anomaly which affects the ectoderm or mesodermal tissues will likely have an effect on the oral cavity. Some of these anomalies have been intentionally introduced to create new "breeds". BRACHYCEPHALIC SYNDROME Brachycephalic syndrome is a set of dysfunctional anatomical airway variations familiar to veterinarians who deal with Bulldogs, Pugs and Boston Terriers but this syndrome is also a problem in Persian, Himalayan and Burmese cats. Stenotic nares, an elongated soft palate, hypoplastic trachea and everted laryngeal saccules can all inhibit respiration. Mouth breathing, stertor, exercise intolerance and collapse after exercise can be seen. Early surgical intervention to open the nares and shorten the palate will often arrest the development of everted saccules, lower respiratory tract inflammation and cardiac stress. -

Rare Anatomical Variations of Third Molars: Two Cases Reported

Case Report DOI: 10.18231/2278-3784.2018.0021 Rare anatomical variations of third molars: Two cases reported Ashvini Vadane1,*, Hassaan Kazi2, Amit Sangle3 1Senior Lecturer, 2PG Student, 3Professor, Dept. of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, M.A. Rangoonwala College of Dental Sciences and Research Centre, Pune, Maharashtra, India *Corresponding Author: Ashvini Vadane Email: [email protected] Abstract The size of tooth and appearance are being easily noticed. The crown of the tooth is being affected by the majority of pathological variations in the morphology of tooth. Variations in the morphology of tooth have been a topic of interest to dentists since long time.1 We report here, two rare cases of four-rooted maxillary third molar and three-rooted mandibular third molar. Extraction of such type of teeth is considered to be a difficult task. We had managed extraction of these teeth with absence of any postoperative complications and teeth were being extracted in-toto. Keywords: Maxillary third molar, Mandibular third molar, Morphological variations, Three rooted molar, Four rooted molar. Introduction of Dental Sciences and Research Centre, Pune. Although In this article, we are reporting two rare cases .In the first these teeth were having abnormal and difficult root patterns, case, the maxillary third molar is having four roots and in the we had extracted these teeth in-toto with no postoperative second case, mandibular third molar is having three roots. complications. Fig. 1 shows extracted maxillary third molar Both these incidences are very rare. Extraction of these teeth tooth which is having four roots whereas Fig. 2 indicates is considered to be difficult because of abnormal root extracted mandibular third molar tooth which is having three patterns. -

Lasers in Periodontal Surgery 5 Allen S

Lasers in Periodontal Surgery 5 Allen S. Honigman and John Sulewski 5.1 Introduction The term laser, which stands for light amplification by stimulation of emitted radia- tion, refers to the production of a coherent form of light, usually of a single wave- length. In dentistry, clinical lasers emit either visible or infrared light energy (nonionizing forms of radiation) for surgical, photobiomodulatory, and diagnostic purposes. Investigations into the possible intraoral uses of lasers began in the 1960s, not long after the first laser was developed by American physicist Theodore H. Maiman in 1960 [1]. Reports of clinical applications in periodontology and oral surgery became evident in the 1980s and 1990s. Since then, the use of lasers in dental prac- tice has become increasingly widespread. 5.2 Laser-Tissue Interactions The primary laser-tissue interaction in soft tissue surgery is thermal, whereby the laser light energy is converted to heat. This occurs either when the target tissue itself directly absorbs the laser energy or when heat is conducted to the tissue from con- tact with a hot fiber tip that has been heated by laser energy. Laser photothermal reactions in soft tissue include incision, excision, vaporization, ablation, hemosta- sis, and coagulation. Table 5.1 summarizes the effects of temperature on soft tissue. A. S. Honigman (*) 165256 N. 105th St, Scottsdale, AZ 85255, AZ, USA J. Sulewski Institute for Advanced Laser Dentistry, Cerritos, CA, USA e-mail: [email protected] © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2020 71 S. Nares (ed.), Advances in Periodontal Surgery, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12310-9_5 72 A. -

What the General Dental Practitioner Should Know About Cone Beam Com- Puted Tomograph Technology

What the general dental practitioner should know about cone beam com- puted tomograph technology Magdalena Marinescu Gava1 1 D.D.S. Pirkanmaa Hospital District, Regional Imaging Centre, Tampere, Finland. Abstract Ionising radiation is used in health care for the diagnosis of diseases, for prevention (such as screening for breast can- cer) and for treatment (radiotherapy). The aim of radiation protection is to ensure that radiation is used safely and that exposure of the patient is kept to a minimum. The principles of radiation protection are based on the recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP). To be acceptable, the use of ionising radiation must be justified, optimal, and limited. Dental radiography has been used since the beginning of radiology and now accounts for nearly one-third of the total number of radiological examinations in the European Union. Pantomography is widely used because in one exposure it records the jaws, temporomandibular joints, maxillary sinuses, and dentition. However, when this technique is used, superimposition of structures in the dentomaxillofacial area has been a limitation in mak- ing reliable diagnoses due to the complexity of the anatomy in this region. These shortcomings have led to development of three-dimensional techniques. One of these techniques, cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), is now available for use in everyday general practice. The aim of this paper is to present CBCT’s advantages and limitations when com- pared with alternative imaging techniques and to stress how it may be used safely in general dental practice. Key Words: Medical Subjects, Radiation Protection, Dentistry, Cone-Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) Introduction the complicated human anatomy. -

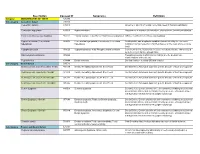

Description Concept ID Synonyms Definition

Description Concept ID Synonyms Definition Category ABNORMALITIES OF TEETH 426390 Subcategory Cementum Defect 399115 Cementum aplasia 346218 Absence or paucity of cellular cementum (seen in hypophosphatasia) Cementum hypoplasia 180000 Hypocementosis Disturbance in structure of cementum, often seen in Juvenile periodontitis Florid cemento-osseous dysplasia 958771 Familial multiple cementoma; Florid osseous dysplasia Diffuse, multifocal cementosseous dysplasia Hypercementosis (Cementation 901056 Cementation hyperplasia; Cementosis; Cementum An idiopathic, non-neoplastic condition characterized by the excessive hyperplasia) hyperplasia buildup of normal cementum (calcified tissue) on the roots of one or more teeth Hypophosphatasia 976620 Hypophosphatasia mild; Phosphoethanol-aminuria Cementum defect; Autosomal recessive hereditary disease characterized by deficiency of alkaline phosphatase Odontohypophosphatasia 976622 Hypophosphatasia in which dental findings are the predominant manifestations of the disease Pulp sclerosis 179199 Dentin sclerosis Dentinal reaction to aging OR mild irritation Subcategory Dentin Defect 515523 Dentinogenesis imperfecta (Shell Teeth) 856459 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; Autosomal dominant genetic disorder of tooth development Dentinogenesis Imperfecta - Shield I 977473 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; Autosomal dominant genetic disorder of tooth development Dentinogenesis Imperfecta - Shield II 976722 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; -

Treatment of Localized Gingival Recessions: Part I. Lateral Sliding

lus and root surface roughness. The subjects were given Treatment of Localized oral hygiene instruction including toothbrushing and dental flossing techniques. An appointment for the sur• Gingival Recessions gical procedure generally was arranged 7 to 10 days after Part I. Lateral Sliding Flap this initial procedure. At that time the following measurements were re• corded (Fig. 1): (1) From the cemento-enamel junction by (or apical margin of a restoration) to the gingival margin; (2) the crevice or pocket depth; (3) the width of keratin• EMILIO A. GUINARD, D.D.S., M.S.* ized gingiva (including the free and attached gingiva) RAUL G. CAFFESSE, D.D.S., M.S., DR. from the gingival margin to the mucogingival line; and (4) the width of the gingival recession at the cemento- ODONT.† enamel junction. Measurements 1, 2, and 3 also were recorded at the neighboring tooth. The tooth adjacent to the area of recession with the lesser clinical recession was A LOCALIZED GINGIVAL recession constitutes a special selected as a donor or control site. The measurements therapeutic problem that often requires some form of 1 always were taken at the midline of the facial aspect of mucogingival surgery. In 1956, Grupe and Warren in• the tooth. A Marquis M-l* periodontal probe, calibrated troduced the lateral sliding flap operation to gain at• in four color coded segments was used. The same mea• tached gingiva and to cover areas with localized gingival surements were repeated at 1, 3 and 6 months after recession. They reported that the lateral sliding flap surgery. Photographs also were taken pre- and postop• provided a satisfactory solution to the problem of de• nuded root surfaces.1 However, one of the essential fea• eratively (Fig.