Education and Training MONITOR 2018 Netherlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Participants

List of participants Conference of European Statisticians 69th Plenary Session, hybrid Wednesday, June 23 – Friday 25 June 2021 Registered participants Governments Albania Ms. Elsa DHULI Director General Institute of Statistics Ms. Vjollca SIMONI Head of International Cooperation and European Integration Sector Institute of Statistics Albania Argentina Sr. Joaquin MARCONI Advisor in International Relations, INDEC Mr. Nicolás PETRESKY International Relations Coordinator National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INDEC) Elena HASAPOV ARAGONÉS National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INDEC) Armenia Mr. Stepan MNATSAKANYAN President Statistical Committee of the Republic of Armenia Ms. Anahit SAFYAN Member of the State Council on Statistics Statistical Committee of RA Australia Mr. David GRUEN Australian Statistician Australian Bureau of Statistics 1 Ms. Teresa DICKINSON Deputy Australian Statistician Australian Bureau of Statistics Ms. Helen WILSON Deputy Australian Statistician Australian Bureau of Statistics Austria Mr. Tobias THOMAS Director General Statistics Austria Ms. Brigitte GRANDITS Head International Relation Statistics Austria Azerbaijan Mr. Farhad ALIYEV Deputy Head of Department State Statistical Committee Mr. Yusif YUSIFOV Deputy Chairman The State Statistical Committee Belarus Ms. Inna MEDVEDEVA Chairperson National Statistical Committee of the Republic of Belarus Ms. Irina MAZAISKAYA Head of International Cooperation and Statistical Information Dissemination Department National Statistical Committee of the Republic of Belarus Ms. Elena KUKHAREVICH First Deputy Chairperson National Statistical Committee of the Republic of Belarus Belgium Mr. Roeland BEERTEN Flanders Statistics Authority Mr. Olivier GODDEERIS Head of international Strategy and coordination Statistics Belgium 2 Bosnia and Herzegovina Ms. Vesna ĆUŽIĆ Director Agency for Statistics Brazil Mr. Eduardo RIOS NETO President Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística - IBGE Sra. -

Annual Report 2013

Annual Report for 2013 Annual Report for 2013 Publisher Statistics Netherlands Henri Faasdreef 312, 2492 JP The Hague www.cbs.nl Prepress: Statistics Netherlands, Grafimedia Design: Edenspiekermann Information Telephone +31 88 570 70 70, fax +31 70 337 59 94 Via contact form: www.cbs.nl/information © Statistics Netherlands, The Hague/Heerlen 2013. Reproduction is permitted, provided Statistics Netherlands is quoted as the source. The original financial statements were drafted in Dutch. This document is an English translation of the original. In the case of any discrepancies between the English and the Dutch text, the latter will prevail. Contents 1. Report of the Director General of Statistics Netherlands 4 2. Central Commission for Statistics 9 3. General 12 3.1 International trends 13 3.2 Collaborative arrangements 14 3.3 Services and communication 18 4. Statistical programme 21 4.1 Programme renewal 22 4.2 Standard statistical programme 22 4.3 New European obligations in 2013 34 5. Methodology, quality and process renewal 35 5.1 Methodology and research 36 5.2 Innovation 37 5.3 Process renewal 38 5.4 Quality and quality assurance 39 6. Operations 41 6.1 Human resources 42 6.2 Risk management 44 6.3 Performance indicators 46 6.4 Reduction of response burden for industry 48 6.5 External accounting model 49 7. Financial statements for 2013 53 Appendix 81 Appendix A Programme Renewal 82 Appendix B Actual output per theme 90 Appendix C Advisory Boards 91 Appendix D Organisation (31 December 2013) 92 Appendix E Guide 93 Appendix F List of Dutch and international abbreviations 95 Contents 3 1. -

Muslim Fertility , Religion and Religiousness

1 02/21/07 Fertility and Religiousness Among European Muslims Charles F. Westoff and Tomas Frejka There seems to be a popular belief that Muslim fertility in Europe is much higher than that of non-Muslims. Part of this belief stems from the general impression of high fertility in some Muslim countries in the Middle East, Asia and Africa. This notion is typically transferred to Muslims living in Europe with their increasing migration along with concerns about numbers and assimilability into European society. I The first part of this paper addresses the question of how much difference there is between Muslim and non-Muslim fertility in Europe (in those countries where such information is available). At the beginning of the 21 st century, there are estimated to be approximately 40 – 50 million Muslims in Europe. Almost all of the Muslims in Central and Eastern Europe live in the Balkans. (Kosovo, although formally part of Serbia, is listed as a country in Table 1). In Western Europe the majority of Muslims immigrated after the Second World War. The post-war economic reconstruction and boom required considerably more labor than was domestically available. There were two principal types of immigration to Western Europe: (a) from countries of the respective former colonial empires; and (b) from Southern Europe, the former Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and Turkey. As much of this immigration took place during the 1950s and 1960s large proportions of present-day Muslims are second and third generation descendants. Immigrants to France came mostly from the former North African colonies Algeria (± 35 percent), Morocco (25 percent) and Tunisia (10 percent), and also from Turkey (10 percent). -

Celebrating the Establishment, Development and Evolution of Statistical Offices Worldwide: a Tribute to John Koren

Statistical Journal of the IAOS 33 (2017) 337–372 337 DOI 10.3233/SJI-161028 IOS Press Celebrating the establishment, development and evolution of statistical offices worldwide: A tribute to John Koren Catherine Michalopouloua,∗ and Angelos Mimisb aDepartment of Social Policy, Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences, Athens, Greece bDepartment of Economic and Regional Development, Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences, Athens, Greece Abstract. This paper describes the establishment, development and evolution of national statistical offices worldwide. It is written to commemorate John Koren and other writers who more than a century ago published national statistical histories. We distinguish four broad periods: the establishment of the first statistical offices (1800–1914); the development after World War I and including World War II (1918–1944); the development after World War II including the extraordinary work of the United Nations Statistical Commission (1945–1974); and, finally, the development since 1975. Also, we report on what has been called a “dark side of numbers”, i.e. “how data and data systems have been used to assist in planning and carrying out a wide range of serious human rights abuses throughout the world”. Keywords: National Statistical Offices, United Nations Statistical Commission, United Nations Statistics Division, organizational structure, human rights 1. Introduction limitations to this power. The limitations in question are not constitutional ones, but constraints that now Westergaard [57] labeled the period from 1830 to seemed to exist independently of any formal arrange- 1849 as the “era of enthusiasm” in statistics to indi- ments of government.... The ‘era of enthusiasm’ in cate the increasing scale of their collection. -

The Netherlands's Effort to Phase out and Rationalise Its Fossil-Fuel

The Netherlands’s Effort to Phase Out and Rationalise its Fossil-Fuel Subsidies An OECD/IEA review of fossil-fuel subsidies in the Netherlands PUBE 2 This report was prepared by Assia Elgouacem (OECD) and Peter Journeay-Kaler (IEA) under the supervision of Nathalie Girouard, Head of the Environmental Performance and Information Division in Environmental Directorate of the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development and Aad van Bohemen, Head of the Energy Policy and Security Division at the International Energy Agency. The authors are grateful for valuable feedback from colleagues at the OECD, Kurt Van Dender, Justine Garrett, Rachel Bae and Mark Mateo. Stakeholder comments from Laurie van der Burg (Oil Change International) and Ronald Steenblik (International Institute for Sustainable Development), Herman Volleberg (Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving) were also taken into account. THE NETHERLANDS’S EFFORT TO PHASE OUT AND RATIONALISE ITS FOSSIL-FUEL SUBSIDIES © OECD 2020 3 Table of contents The Netherlands’s Effort to Phase Out and Rationalise its Fossil-Fuel Subsidies 1 Acronyms and Abbreviations 4 Executive Summary 6 1. Introduction 8 2. Energy sector overview 11 3. Fossil-fuel subsidies in the Netherlands 21 4. Assessments and Recommendations 35 References 41 Tables Table 1. Indicative 2030 emission reduction targets, by sector 19 Table 2. The Netherlands’ 2020 and 2030 energy targets and 2018 status (EU definitions and data) 20 Table 3. The 13 fossil-fuel subsidies identified in the self-report of the Netherlands 22 Table 4. Scope and tax preferences of identified fossil-fuel subsidies in the EU ETD 23 Table 5. Energy tax and surcharge for renewable energy, 2019 and 2020 31 Table 6. -

Participants

Name Country Organisation Email Address Eden Brinkley Australia Australian Bureau of Statistics eden .brinkley@abs .gov.au Francesca Peressini Australia Central Statistics Office francesca .peressini@cso .ie until 9/2000 then Australian Bureau of Statistics f.pressini@abs .gov.au Armin Braslins (Canada Statistics Canada [email protected] Gaetan St. Louis Canada Statistics Canada [email protected] Menard Mario Canada !Statistics Canada mario.menard@statcan .ca Carsten Pedersen Denmark Statistics Denmark [email protected] Leif Bochis Denmark Statistics Denmark [email protected] Pirjo Hyytiainen Finland Statistics Finland [email protected] Jarmo Lauri Finland Statistics Finland [email protected] Matti Simpanen Finland Statistics Finland [email protected] Timo Narvanen Finland Statistics Finland [email protected] Vasa Kuusela Finland Statistics Finland [email protected] Rene Paux France INSEE France rene.paux@insee .fr Dominique Maire France INSEE France [email protected] Gilles LucianiFrance INSEE France [email protected] Philippe Meunier (France INSEE France [email protected] Christophe Alviset France INSEE France [email protected] Elmar Wain Germany Federal Statistical Office [email protected] Sylvia von Wrisberg Germany Hajnalka Bertok Hungary Hungarian Central Statistical Office [email protected] .hu Zsolt Papp Hungary (Hungarian Central Statistical Office zsolt.papp@office .ksh.hu Rut Jonsdottir Iceland Statistics Iceland [email protected] David Davidson Iceland -

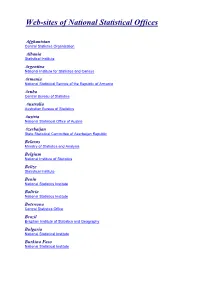

Web-Sites of National Statistical Offices

Web-sites of National Statistical Offices Afghanistan Central Statistics Organization Albania Statistical Institute Argentina National Institute for Statistics and Census Armenia National Statistical Service of the Republic of Armenia Aruba Central Bureau of Statistics Australia Australian Bureau of Statistics Austria National Statistical Office of Austria Azerbaijan State Statistical Committee of Azerbaijan Republic Belarus Ministry of Statistics and Analysis Belgium National Institute of Statistics Belize Statistical Institute Benin National Statistics Institute Bolivia National Statistics Institute Botswana Central Statistics Office Brazil Brazilian Institute of Statistics and Geography Bulgaria National Statistical Institute Burkina Faso National Statistical Institute Cambodia National Institute of Statistics Cameroon National Institute of Statistics Canada Statistics Canada Cape Verde National Statistical Office Central African Republic General Directorate of Statistics and Economic and Social Studies Chile National Statistical Institute of Chile China National Bureau of Statistics Colombia National Administrative Department for Statistics Cook Islands Statistics Office Costa Rica National Statistical Institute Côte d'Ivoire National Statistical Institute Croatia Croatian Bureau of Statistics Cuba National statistical institute Cyprus Statistical Service of Cyprus Czech Republic Czech Statistical Office Denmark Statistics Denmark Dominican Republic National Statistical Office Ecuador National Institute for Statistics and Census Egypt -

Netherlands Official Statistics

Netherlands Official Statistics Volume 14, Summer 1999 Voorburg Heerlen Prinses Beatrixlaan 428 Kloosterweg 1 P.O. Box 4000 P.O. Box 4481 2270 JM Voorburg (Netherlands) 6401 CZ Heerlen (Netherlands) Telephone : . .31 (070) 337 38 00 Telephone : . .31 (045) 570 60 00 Fax : . .31 (070) 387 74 29 Fax : . .31 (045) 572 74 40 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.cbs.nl Key figure A-125/1999 © Statistics Netherlands, Voorburg/Heerlen 1999. Quotation of source is compulsory. Reproduction is permitted for own use or internal use. Subscription: Dfl. 42.00 per year Price per copy: Dfl. 20.00 ISSN 0920-2048 Postage will be charged. Contents Business cycle surveys for the manufacturing industry 4 Ad Abrahamse and Thom Werkhoven Testing effects of incentives and a condensed questionnaire on response rates 9 Jan van den Brakel and Robbert Renssen Digital topographical maps as a source for the compilation of area-based statistics 13 Mathieu Vliegen and Niek van Leeuwen Household scenarios for the European Union: methodology and main results 17 Maarten Alders and Dorien Manting Analysing well-being in relation to characteristics of the population 28 Gerda Gringhuis and Abby Israëls Atlas of plant communities in the Netherlands 34 Lodewijk van Duuren, Joop Schaminée and Eddy Weeda (amendment) International papers and contributions published by Statistics Netherlands staff in 1998 37 Editor in chief Jeroen Pannekoek Coordinating editor Lieneke Hoeksma Editors Bart F.M. Bakker Gert P. den Bakker Ruud A.A.J. Luijendijk Cornelis J. Veenstra Business cycle surveys for the manufacturing industry Ad Abrahamse and Thom Werkhoven releases are published in the main national newspapers every month, even when things are relatively quiet on the economic front. -

City Data from LFS and Big Data

City data from LFS and big data Project 2016CE16BAT107 Final report February 2019 EUROPEAN COMMISSION Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy Directorate Policy Unit Policy Development and Economic Analysis. Contact: Moray Gilland E-mail: [email protected] European Commission B-1049 Brussels Manuscript completed in February 2019. This document has been prepared for the European Commission however, it reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use, which may be made of the information contained therein. The European Commission is not liable for any consequence stemming from the reuse of this publication. More information on the European Union is available on the internet (http://europa.eu). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2019 PDF ISBN 978-92-76-08678-9 doi:10.2776/120066 KN-02-19-484-EN-N © European Union, 2019 Reuse is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. The reuse policy of European Commission documents is regulated by Decision 2011/833/EU (OJ L 330, 14.12.2011, p. 39). EUROPEAN COMMISSION City data from LFS and Big Data Project 2016CE16BAT107 Final report Prepared by Johan van der Valk, Martijn Souren, Martijn Tennekes, Shan Shah, May Offermans, Edwin de Jonge, Jan van der Laan, Yvonne Gootzen, Sander Scholtus, Anna Mitriaieva (Statistics Netherlands) Benjamin Sakarovitch (INSEE) Sandra Hadam, Markus Zwick, Martina Rengers (Destatis) Alex Kowarik, Marlene Weinauer, Johannes Gussenbauer (Statistics Austria) Marc Debusschere, Anja Termote (Statbel) Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy 2019 EN Contents SUMMARY .................................................................................................................... 1 1. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 3 2. LABOUR FORCE SURVEY ........................................................................................ -

Statistical Yearbook of the Netherlands 2004

Statistical Yearbook of the Netherlands 2004 Statistics Netherlands Preface Statistics Netherlands has a long tradition in the publication of annual figures and yearbooks. The Statistical Yearbook has been the most popular publication by Statistics Netherlands for decades. This latest edition again provides facts and figures on virtually all aspects of Dutch society. It is an invaluable resource for a quick exploration of the economy, population issues, education, health care, crime, culture, the environment, housing, and many other topics. This year’s volume is structured in exactly the same way as last year. It contains the data available at the end of November 2003. For current updates please check the Statline Database at Statistics Netherlands, which is in the process of being translated into English. It can be accessed free of charge at www.cbs.nl. G. van der Veen Director General of Statistics Voorburg / Heerlen, April 2004 Preface Statistical Yearbook 2004 3 Published by Explanation of symbols Statistics Netherlands Prinses Beatrixlaan 428 . = figure not available 2273 XZ Voorburg * = provisional figure The Netherlands x = publication prohibited (confidential figure) Lay out – = nil Statistics Netherlands 0 (0.0) = less than half of unit concerned Facility services department blank = not applicable < = fewer / less / smaller than > = more / greater than Cover design ≤ = fewer / less / smaller than or equal to WAT ontwerpers (Utrecht) ≥ = more / greater than or equal to 2003-2004 = 2003 to 2004 inclusive Print 2003/2004 = average of 2003 up to and Opmeer | De Bink | TDS v.o.f., The Hague including 2004 2003/’04 = crop year, financial year, school Translation year etc. beginning in 2003 and Statistics Netherlands ending in 2004 Rita Gircour Due to rounding, some totals may not correspond with Information the sum of the separate figures E-mail [email protected] How to order Obtainable from The Sdu publishers P.O. -

Kim | Cycling Facts

Cycling Facts Netherlands Institute for Transport Policy Analysis | KiM Lucas Harms & Maarten Kansen Contents 1 Facts and figures on bicycle use 2 Trends in bicycle use 3 Possession and use of e-bikes 4 Effects of bicycle use Netherlands Institute for Transport Policy Analysis | Cycling Facts 1 Facts and figures on bicycle use 2 Trends in bicycle use 3 Possession and use of e-bikes 4 Effects of bicycle use 1 Facts and figures on bicycle use Bicycles account for 25% of daily mobility1 Distribution of trips by Distribution of bicycle kilometres mode of travel, by purpose, • More than one-quarter of all trips made by Dutch residents are travelled by bicycle. % • 2016 saw a total of 4.5 billion bicycle trips, spanning a distance of % % 15.5 billion bicycle kilometres. % • More than one-third of all bicycle kilometres are travelled for % leisure purposes; one-quarter involve work-related trips. % % % Bicycle Bus, tram, subway Leisure Shopping Car Walking Work Other Train Other Education 1 Statistics Netherlands (CBS) (Netherlands Travel Survey (OViN) 2016 – data adapted by KiM). Netherlands Institute for Transport Policy Analysis | Cycling Facts 1 Facts and figures on bicycle use 2 Trends in bicycle use 3 Possession and use of e-bikes 4 Effects of bicycle use In the Netherlands, bicycles outnumber residents2 The Netherlands is the unrivalled number one bicycling nation4 • The Netherlands accommodates 17 million inhabitants and Figure: Proportion of bicycle use as a percentage of total number of trips in several countries. 23 million bicycles. • Increasingly more Dutch residents own an e-bike; of the 30 23 million bicycles, 2 million are e-bikes. -

The System of Social Statistical Datasets of Statistics Netherlands: an Integral Approach to the Production of Register-Based Social Statistics

Statistical Journal of the IAOS 30 (2014) 411–424 411 DOI 10.3233/SJI-140803 IOS Press The System of social statistical datasets of Statistics Netherlands: An integral approach to the production of register-based social statistics Bart F.M. Bakkera,b,∗, Johan van Rooijena and Leo van Toora aStatistics Netherlands, Den Haag, The Netherlands bVU University Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Abstract. More and more countries are using register data to replace traditional Censuses. Moreover, official statistics as well as research are increasingly based on register data or combinations of survey and register data. Register-based statistics offer wonderful new opportunities. At the same time, they require a new approach to how data are processed and managed. In this article, we present the System of social statistical datasets (SSD), a system of interlinked and standardized registers and surveys. All production processes within Statistics Netherlands that pertain to social or spatial statistics converge in the SSD, which thus constitutes a shared output-oriented system. The SSD contains a wealth of information on persons, households, jobs, benefits, pensions, education, hospitalizations, crime reports, dwellings, vehicles and more. In the Netherlands it is the most important source for official social statistics and, because the data are available on request by means of remote access, also very popular in the social sciences. This article describes the contents of the SSD as well as the underlying process and organization, and demonstrates its possibilities. Keywords: Registers, administrative data, data processing, micro-integration 1. Introduction ables to correct for non-response bias, or to replace sample survey data altogether.