An Exegetical Exposition of Psalm 132

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

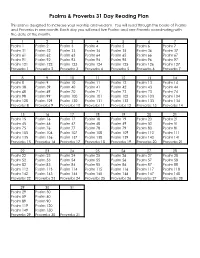

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan This plan is designed to increase your worship and wisdom. You will read through the books of Psalms and Proverbs in one month. Each day you will read five Psalms and one Proverb coordinating with the date of the month. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Psalm 1 Psalm 2 Psalm 3 Psalm 4 Psalm 5 Psalm 6 Psalm 7 Psalm 31 Psalm 32 Psalm 33 Psalm 34 Psalm 35 Psalm 36 Psalm 37 Psalm 61 Psalm 62 Psalm 63 Psalm 64 Psalm 65 Psalm 66 Psalm 67 Psalm 91 Psalm 92 Psalm 93 Psalm 94 Psalm 95 Psalm 96 Psalm 97 Psalm 121 Psalm 122 Psalm 123 Psalm 124 Psalm 125 Psalm 126 Psalm 127 Proverbs 1 Proverbs 2 Proverbs 3 Proverbs 4 Proverbs 5 Proverbs 6 Proverbs 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Psalm 8 Psalm 9 Psalm 10 Psalm 11 Psalm 12 Psalm 13 Psalm 14 Psalm 38 Psalm 39 Psalm 40 Psalm 41 Psalm 42 Psalm 43 Psalm 44 Psalm 68 Psalm 69 Psalm 70 Psalm 71 Psalm 72 Psalm 73 Psalm 74 Psalm 98 Psalm 99 Psalm 100 Psalm 101 Psalm 102 Psalm 103 Psalm 104 Psalm 128 Psalm 129 Psalm 130 Psalm 131 Psalm 132 Psalm 133 Psalm 134 Proverbs 8 Proverbs 9 Proverbs 10 Proverbs 11 Proverbs 12 Proverbs 13 Proverbs 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Psalm 15 Psalm 16 Psalm 17 Psalm 18 Psalm 19 Psalm 20 Psalm 21 Psalm 45 Psalm 46 Psalm 47 Psalm 48 Psalm 49 Psalm 50 Psalm 51 Psalm 75 Psalm 76 Psalm 77 Psalm 78 Psalm 79 Psalm 80 Psalm 81 Psalm 105 Psalm 106 Psalm 107 Psalm 108 Psalm 109 Psalm 110 Psalm 111 Psalm 135 Psalm 136 Psalm 137 Psalm 138 Psalm 139 Psalm 140 Psalm 141 Proverbs 15 Proverbs 16 Proverbs 17 Proverbs 18 Proverbs 19 Proverbs 20 Proverbs 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Psalm 22 Psalm 23 Psalm 24 Psalm 25 Psalm 26 Psalm 27 Psalm 28 Psalm 52 Psalm 53 Psalm 54 Psalm 55 Psalm 56 Psalm 57 Psalm 58 Psalm 82 Psalm 83 Psalm 84 Psalm 85 Psalm 86 Psalm 87 Psalm 88 Psalm 112 Psalm 113 Psalm 114 Psalm 115 Psalm 116 Psalm 117 Psalm 118 Psalm 142 Psalm 143 Psalm 144 Psalm 145 Psalm 146 Psalm 147 Psalm 148 Proverbs 22 Proverbs 23 Proverbs 24 Proverbs 25 Proverbs 26 Proverbs 27 Proverbs 28 29 30 31 Psalm 29 Psalm 30 Psalm 59 Psalm 60 Psalm 89 Psalm 90 Psalm 119 Psalm 120 Psalm 149 Psalm 150 Proverbs 29 Proverbs 30 Proverbs 31. -

1 Refine Women's Ministry Psalm 120 – 134: Songs of Ascent- Part 2

Refine Women’s Ministry Psalm 120 – 134: Songs of Ascent- Part 2 March 31, 2021 by Kim Peelen Man’s chief work is the praise of God. Augustine How lovely is the sanctuary in the eyes of those who are truly sanctified! Matthew Henry Today we complete a brief ‘fly-over’ of Psalms 120 – 134, known as Songs of Ascent or the Songs of Degrees. Easton’s Bible Dictionary gives this definition: “song of steps, a title given to each of these fifteen psalms, 120-134 inclusive. The probable origin of this name is the circumstance that these psalms came to be sung by the people on the ascents or goings up to Jerusalem to attend the three great festivals (Deut. 16:16). They were well fitted for being sung by the way from their peculiar form, and from the sentiments they express. They are characterized by brevity, by a key-word, by epanaphora [i.e., repetition], and by their epigrammatic style...More than half of them are cheerful, and all of them hopeful." Also called "Pilgrim Songs”, David wrote four, Solomon one (127), and the rest are anonymous. The pilgrims were commanded in the Law to celebrate these festivals in the place where the LORD chooses to establish His name, and at the time of Moses it was the Tabernacle, during King David it was Mt. Zion because the Ark of the Covenant rested there, and later, it was Solomon’s Temple. These physical spaces became significant because it represented where God chose to dwell among His people. The three annual holidays, also called ‘pilgrim feasts’ because all adult males in Israel were required to travel to the sanctuary in order to participate, are Passover (Feast of Unleavened Bread), Feast of Weeks (Pentecost), and Feast of Tabernacles (Ingathering). -

Royal Psalms Holy One to Supply by by Sister Michelle Mohr the Help of Grace

Oblates Newsletter for Oblates of the Sisters of St. Benedict of Ferdinand, Indiana July 2012 First of all, every time you begin a good work, you must pray to God most earnestly to bring it to perfection…. what “is not possible to us by nature, let us ask the Royal Psalms Holy One to supply by By Sister Michelle Mohr the help of grace. In his book, “Praying the Psalms,” Walter Bruggemann poses two considerations when we pray the psalms. The first —Rule of St. Benedict Prologue 4, 41 consideration is: What do we find in the psalms that is already there, and the second is: What do we bring to the psalms out of our own lives. The royal psalms, our topic today, are categorized according to their subject matter of kingship. Specifically the royal psalms A recipe for success deal with the spiritual role of kings in the worship of God. “Begin with a prayer, The Royal Psalms live and work in God’s Psalm 2, Psalm 18, Psalm 20, Psalm 21, Psalm 45, Psalm 72, Psalm 101, Psalm 110, Psalm 132, Psalm 144 presence, His” grace will strengthen you, and God Each of these psalms makes explicit references to the subject, the king. Although will be glorified in all it is possible that other psalms which do not mention the king directly, may have things.” been written for royalty, e. g. Psalm 22, they are not labeled royal psalms. In the book of Samuel we have the account of the people going to Samuel and demanding him to appoint a king to rule over them. -

Daily Seeking God Seeking God in His Word Seeking God “He Awakens Me Morning by Morning, He Awakens My Ear to Hear As the Sharing the Everlasting Gospel Learned

Village Church Daily Seeking God Seeking God in His Word Seeking God “He awakens me morning by morning, He awakens my ear to hear as the Sharing the Everlasting Gospel learned. The Lord has opened my ears.” Isaiah 50:4 Serving Others Ask - God to be present before your devotion time. Invite Him to speak to June 2021 you through His Word by bringing to your attention something He wants you Date Old Test. New Test. Psalms Proverbs P & K to understand, learn or practice. Tue 1-Jun Numbers 21 Revelation 12 Psalm 131 Proverbs 21:13 Chapter 19 Wed 2-Jun Numbers 22 Revelation 13 Psalm 132 Proverbs 21:14 Chapter 20 Read - selected section of Scripture deliberately. Take note of the words and Thu 3-Jun Numbers 23 Revelation 14 Psalm 133 Proverbs 21:15 Ch. 21, p. 254-259 phrases that catch your attention and/or intrigue you. Read them a second Fri 4-Jun Numbers 24 Revelation 15 Psalm 134 Proverbs 21:16 Ch. 21, p. 260-264 time (or more). Sat 5-Jun Numbers 25 Revelation 16 Psalm 135 Proverbs 21:17 Ch. 22, p. 265-270 Reflect - on what grabs your attention. What connections are there with our Sun 6-Jun Numbers 26 Revelation 17 Psalm 136 Proverbs 21:18 Ch. 22, p. 271-278 life? How might God be speaking to you through these words? Stop long Mon 7-Jun Psalm 137 Proverbs 21:19 Ch. 23, p. 279-284 Numbers 27 Revelation 18 enough to let this take root. Thank God for speaking to your heart. -

Psalm 131-133

Book of Psalms Psalms 131-133 Psalms 120-134 are called “songs of degrees” or “songs of ascent.” God’s people sang them as they traveled to Jerusalem for the three sacred feasts (Passover, Pentecost, and Tabernacles). They are called “songs of ascent or degrees” because Jerusalem is about 2,700 feet in elevation. Jewish worshipers sang these jubilant songs as they made their pilgrimage upward to Jerusalem. Four of the songs were written by David (Ps. 122, 124, 131, and 133). Psalm 131 – A Childlike Faith in God The Bible calls us to be childlike in our faith (Matt. 18:3). As a believer matures spiritually, he becomes more childlike in his faith. In the same way a child depends on his parents to meet his needs, we should look to God in simple dependence. 1. A childlike humility before God (vs. 1) David rejects pride, haughtiness, and selfish ambition. God resists the proud, but gives grace to the humble (Jas. 4:6). 2. A childlike hush before God (vs. 2) David describes himself as a child who is old enough to be weaned, yet not old enough to care for himself. He has learned to be quietly submissive while relying on God. 3. A childlike hope in God (vs. 3) David urges God’s people to hope in Him. Hope is the assurance that God is working all things for the ultimate good of His people (Rom. 8:28). Steven Lawson comments: “This psalm should be the confession of all believers. Every saint should have a childlike faith in God. -

A Zeal for Worship and the Oath of God

A Zeal for Worship and the Oath of God Psalm 132 Sunday, May 17, 2020 These Psalms of Ascent speak to our hearts in this season. In Psalm 132 we find a reminder of our heart for worship. We also get to look again at the promises of God. Psalm 132 is about the desire to see the Ark of the Covenant placed in the temple in Jerusalem. The first half of the Psalm (vs. 1–10) is about David’s oath in which he promised to bring the Ark into a permanent temple. The second half (vs. 11–18) records God’s corresponding oath of an everlasting dynasty. Charles Spurgeon said: “A joyful song indeed: let all pilgrims to the New Jerusalem sing it often. The degrees or ascents are very visible; the theme ascends step by step from “afflictions” to a “crown,” from “remember David,” to “I will make the horn of David to bud.” The latter half is like the over-arching sky bending above “the fields of the wood” which are found in the resolves and prayers of the former portion.” I. Be thoughtful of God’s presence (1-10) David’s joy and delight in his God made him long for a home for the Ark of the Lord, the symbolic presence of God. Let’s read together the historical account of David’s thoughtfulness of God’s presence in 2 Samuel 7:8b-17 What seems so striking to me is the way that David is depicted as a person enduring hardship but not being preoccupied by his hardship but preoccupied by a desire to honor the Lord. -

Psalms of Ascent

“Your word is a lamp to my feet, a light for my path” (Ps. 119:105) 51st International Jewish-Christian Bible Week Psalms 119 to 134 28th July to 4th August 2019 PSALMS OF ASCENT Shani Tzoref I am excited to be joining you here at Osnabruck for the Jewish-Christian Bible week. I am very grateful for the kind invitation and for the opportunity that it has given me to think about the Psalms of Ascent. Since my expertise is in Hebrew Bible and Jewish texts, I have decided to focus this talk on biblical and rabbinic texts, and I am looking forward to learning more from you about Christian exegesis and reception in the coming days. In my study of the Psalms, I have found a most useful rubric to be Hermann Gunkel’s form-critical approach. I would even say that it has served me as a key to deciphering the corpus, helping me discern sense and structure amidst the poetic language. My personal religious experience of Tehillim as prayer had given me an early appreciation of the biblical Psalter, but in a way that was quite atomized—individual phrases had strong resonances for me; I had less sensitivity to larger blocs of text and literary cohesion. I’d like to use our time together to consider the Psalms of As- cent through two of Gunkel’s form-critical lenses, Sitz-im-Leben and Gattung, and concluding with an intertextual glance at Solomon’s prayer at the dedication of the Temple in 1 Kings 8 and 2 Chronicles 6. -

1 and 2 Samuel

1 and 2 Samuel INFORMATION FOR SMALL GROUP LEADERS GOING DEEP: Author and Title (Information gathered from the ESV study Bible) The Hebrew title “Samuel” refers to Samuel as the key figure in 1–2 Samuel, the one who established the monarchy in Israel by anointing first Saul and then David; Samuel was the kingmaker in the history of ancient Israel. In the Hebrew Bible, the first and second books of Samuel are counted among the “Former Prophets” (Joshua–2 Kings). The Greek translation, the Septuagint, divides Samuel and Kings into the four “Books of Kingdoms”; thus 1–2 Samuel are 1–2 Kingdoms. In the Latin Vulgate and Douay Bible they are called 1–2 Kings. The author or authors of 1–2 Samuel are not known. First Chronicles 29:29–30 implies that Samuel (or perhaps his disciples) left written records, but because his death is mentioned in 1 Samuel 25, he could not have written most of Samuel. Theme The central theme of the books of Samuel is God’s exercising of his cosmic kingship by inaugurating a Davidic dynasty (“house”) in Israel (2 Samuel 7; Psalm 89), not a Saulide one (1 Sam. 13:13–14; 15:28), and by electing the holy city Zion (Jerusalem; 2 Samuel 6; Psalm 132) as the place where David’s successor will establish the temple (“house”) for the worship of the divine King Yahweh (see 2 Sam. 24:18). The Davidic “covenant” (2 Samuel 7; Ps. 89:3) entitled 1 Matthew to put David at the center of the genealogical history of the divine plan of salvation (Matt. -

Prayer Guide 1 2 Pray First Table of Contents

Prayer Guide 1 2 Pray First Table of Contents Lifestyle Prayer ...................................................................... 1 The Lord’s Prayer .................................................................. 3 Tabernacle Prayer ................................................................. 7 Prayer and Scripture Devotional ................................... 13 Warfare Prayers ..................................................................... 17 Personal Prayer Targets ..................................................... 23 My Prayer Journal ................................................................. 30 One-Year Bible Reading Plan........................................... 33 Prayer Guide 3 PRAY FIRST Dear Reader, Since the beginning of our church, prayer has been a lifeline. One of our core values is that we are Spirit-led, so in every situation, our motto has simply been- pray first. We not only pray first, but we pray last and pray in the middle. This has been the secret to all of our decisions and has brought health not only to the church but peace in my own personal life. I’ve discovered however, many times people act first then want God to rescue them out of that situation, but prayer should be our premier choice, not our last settled scheme. Recognizing the value of prayer is not enough. In order for it to become a part of our life, it needs to become something we look forward to doing, something that doesn’t give us a headache or makes us feel bad doing, but something that rejuvenates us, giving us hope and tangible peace. I’m convinced most people don’t enjoy prayer because honestly, they’ve never been taught how to pray or they don’t know the power of prayer. That’s where this simple prayer journal can help. Using several prayer models out of the Bible and having some guides to make prayer more personal, this booklet is designed to bring joy into your time with God. -

Psalm 132 "Yahweh's Revelation, in Response to Prayer, of His Choice to Reside in Zion, Blessing It Through His Davidic Messiah"

Psalm 132 "Yahweh's Revelation, in Response to Prayer, of His Choice to Reside in Zion, Blessing It Through His Davidic Messiah" (A Song of Ascents.)1 Scripture taken from the NEW AMERICAN STANDARD BIBLE ®, Copyright © 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by the Lockman Foundation. Used by permission. (www.Lockman.org) A1 A PRAYER TO YAHWEH TO REMEMBER DAVID'S PASSION, DESPITE OPPOSITION, TO BUILD HIM A HOUSE 132:1-5 B1 A Request to Yahweh to Remember David's Trials 132:1 C1 {1} Remember, O LORD, on David's behalf, C2 All his affliction; B2 A Request to Yahweh to Remember David's Passion Oath to Build Him a House 132:2-5 C1 The Evidence of David's Passion – An Oath 132:2 D1 To Yahweh: {2} How he swore to the LORD D2 To the Mighty One of Jacob: And vowed to the Mighty One 2 of Jacob, C2 The Content of David's Oath 132:3-5 D1 He will not prepare to rest 132:3 E1 {3} "Surely I will not enter my house, E2 Nor lie on my bed; D2 He will not sleep 132:4 E1 {4} I will not give sleep to my eyes E2 Or slumber to my eyelids, 1 Psalm132 Superscription - Song of Ascents: See note on Psalm 120. 2 Psalm 132:2, 5 - Mighty One of Jacob: Mighty One ('abiyr, 46) - used only six times in the Bible, twice here in Ps. 132, five times in connection with Jacob (Gen. 49:24; Ps.132:2, 5; Isa. -

A STUDY of the HEBREW TEXT of PSALM 132 a Thesis Presented In

A STUDY OF THE HEBREW TEXT OF PSALM 132 A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Kathryn Ruth Bartley, B.A. ***** The Ohio State University . 2004 Master's Examination Committee: Dr. Sam Meier, Adviser Dr. Rueben Ahroni Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures ABSTRACT This paper is an exegetical study of Psalm 132, the most frequently discussed psalm among the Songs of Ascents, Psalms 120-134. Psalm 132 stands out from its collection mainly in terms of its length: it is twice the length of any of the other Songs of Ascents. My intent was to compile past and present scholarship and research on this particular psalm and provide a state of the field survey of the psalm. The title over each psalm of the collection, šīr hamma ‘ălōt, is typically seen as the key to understanding the Songs of Ascents as a whole, and thus each psalm individually. In this study, I provide a history of interpretation of the collection and a summary of the early interpretation of Psalm 132. While not certain, it seems that Psalm 132 and the remainder of the šīrē hamma ‘ălōt were pilgrimage songs of some sort. This paper then provides a thorough exegetical study of Psalm 132. I mention problematic and anomalous words and phrases, and provide possible solutions. Whenever possible, the Hebrew Bible and other ancient near eastern texts are used to clarify words and concepts in the psalm. A translation is proposed based upon this study. -

43. Psalms 132-135 Praying Psalm 132 with Jesus

43. Psalms 132-135 Praying Psalm 132 with Jesus Psalm 132 is a ceremonial chant recalling the transfer of the ark to David’s city (2 Samuel 6) and then to the temple (1 Kings 8). It recalls the link between David’s desire to build God a house and God’s promise to build a house (that is, a dynasty) for David (2 Samuel 7). The transfer of the Ark to Jerusalem is being recalled, and perhaps ceremonially re-enacted. ‘Ephrathah’ (verse 6) is the region of Bethlehem, just south of Jerusalem (see 1 Chronicles 4:4). David came from this area. ‘Yearim’ (verse 6) refers to Kiriath- yearim where the ark was installed after being captured back from the Philistines (1 Samuel 6:21 - 7:2). 1O GOD, remember David and the many hardships he endured; 2and how he swore an oath to you, O Mighty One of Jacob: 3‘I will not enter my house or lie down on my bed; 4I will not close my eyes, nor will I sleep, 5till I find a place for GOD, a dwelling place for the Mighty One of Jacob.’ 6We heard of the ark in Ephrathah; we found it in the fields of Yearim. 7‘Let us go to GOD’s house; let us kneel at GOD’s footstool.’ 8Rise up, O GOD, and go to your resting place, you and the ark of your might. 9Let your priests be properly attired, and your faithful shout for joy. 10For your servant David’s sake do not deny audience to your anointed one.