The Pirates' Who's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPD Investigates Hazing

SERVING SAN JOSE STATE UNIVERSITY SINCE 1934 SPA TAN DAILY WWW.THESPARTANDAII,Y.COM VOLUME 122, NUMBER 61 WEDNESDAY, MAY 5, 2004 Beloved alum UPD investigates hazing hospitalized By Tony Burchyns and brawl that resulted in the death of one 33 cm. on April 21, when University legs, and was eventually treated at by student, the Pi Alpha Phi fraternity Police officers responded to Royce Hall Valley Medical Center, the document Maria Villalobos or what's left of it is once again on "medical aid to assist a resident states. Daily Managing Editor and under the gun. This time, the issue is who "was apparently intoxicated and The press release goes on to state, Daily Staff Writer hazing, and according to some wit- unconscious, according to a recent 'Other witnesses at the scene said it drunk driver nesses, members of the now-unofficial UPD press release. was rumored that (the student) was More than a year after its indefinite fraternity were involved. The student had abrasions and suspension for its part in an off-campus The investigation started at 12: swelling on his torso, face, arms and SJSU graduate in serious condition see HAZING, page 4 after being knocked off her bike swim team, the Mountain View flea market By Daniel DeBolt Array of goods found at local Daily Stall Writer Masters. They were visiting Liu's Mother in Santa Rosa at the time A trust fund has been set up of the accident. for Jill Mason, a San Jose State "I saw her in January, and she was talking about how she was fir liganiE1111111111111111E. -

The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse 1

The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse 1 The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Pirates' Who's Who Giving Particulars Of The Lives and Deaths Of The Pirates And Buccaneers Author: Philip Gosse Release Date: October 17, 2006 [EBook #19564] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE PIRATES' WHO'S WHO *** Produced by Suzanne Shell, Christine D. and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net Transcriber's note. Many of the names in this book (even outside quoted passages) are inconsistently spelt. I have chosen to retain the original spelling treating these as author error rather than typographical carelessness. THE PIRATES' The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse 2 WHO'S WHO Giving Particulars of the Lives & Deaths of the Pirates & Buccaneers BY PHILIP GOSSE ILLUSTRATED BURT FRANKLIN: RESEARCH & SOURCE WORKS SERIES 119 Essays in History, Economics & Social Science 51 BURT FRANKLIN NEW YORK Published by BURT FRANKLIN 235 East 44th St., New York 10017 Originally Published: 1924 Printed in the U.S.A. Library of Congress Catalog Card No.: 68-56594 Burt Franklin: Research & Source Works Series 119 Essays in History, Economics & Social Science -

Personnages Marins Historiques Importants

PERSONNAGES MARINS HISTORIQUES IMPORTANTS Années Pays Nom Vie Commentaires d'activité d'origine Nicholas Alvel Début 1603 Angleterre Actif dans la mer Ionienne. XVIIe siècle Pedro Menéndez de 1519-1574 1565 Espagne Amiral espagnol et chasseur de pirates, de Avilés est connu Avilés pour la destruction de l'établissement français de Fort Caroline en 1565. Samuel Axe Début 1629-1645 Angleterre Corsaire anglais au service des Hollandais, Axe a servi les XVIIe siècle Anglais pendant la révolte des gueux contre les Habsbourgs. Sir Andrew Barton 1466-1511 Jusqu'en Écosse Bien que servant sous une lettre de marque écossaise, il est 1511 souvent considéré comme un pirate par les Anglais et les Portugais. Abraham Blauvelt Mort en 1663 1640-1663 Pays-Bas Un des derniers corsaires hollandais du milieu du XVIIe siècle, Blauvelt a cartographié une grande partie de l'Amérique du Sud. Nathaniel Butler Né en 1578 1639 Angleterre Malgré une infructueuse carrière de corsaire, Butler devint gouverneur colonial des Bermudes. Jan de Bouff Début 1602 Pays-Bas Corsaire dunkerquois au service des Habsbourgs durant la XVIIe siècle révolte des gueux. John Callis (Calles) 1558-1587? 1574-1587 Angleterre Pirate gallois actif la long des côtes Sud du Pays de Galles. Hendrik (Enrique) 1581-1643 1600, Pays-Bas Corsaire qui combattit les Habsbourgs durant la révolte des Brower 1643 gueux, il captura la ville de Castro au Chili et l'a conserva pendant deux mois[3]. Thomas Cavendish 1560-1592 1587-1592 Angleterre Pirate ayant attaqué de nombreuses villes et navires espagnols du Nouveau Monde[4],[5],[6],[7],[8]. -

Nurturing Nature During the Golden Age of Piracy Thomas R

The Purdue Historian Volume 8 Article 5 2017 Nurturing Nature During the Golden Age of Piracy Thomas R. Meeks Jr. Purdue University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/puhistorian Part of the History Commons, and the Life Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Meeks, Thomas R. Jr.. "Nurturing Nature During the Golden Age of Piracy." The Purdue Historian 8, 1 (2017). http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/puhistorian/vol8/iss1/5 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Nurturing Nature During the Golden Age of Piracy Cover Page Footnote A special thanks to Heidi and Jordan. This article is available in The urP due Historian: http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/puhistorian/vol8/iss1/5 Meeks: Nurturing Nature During the Golden Age of Piracy Nurturing Nature During the Golden Age of Piracy Thomas Meeks Jr. History 395 [email protected] (847) 774-0721 Published by Purdue e-Pubs, 2017 1 The Purdue Historian, Vol. 8 [2017], Art. 5 th On June 7 , 1692, a cataclysmic earthquake ravaged the flourishing English town of Port Royal, Jamaica. Emmanuel Heath, a local reverend, described the event, “I found the ground rowling [growling] and moving under my feet... we heard the Church and Tower fall... and made toward Morgan’s Fort, which being a wide open place, I thought to be there securest from the falling houses; But as I made toward it, I saw the Earth open and swallow up a multitude of people, and the sea 1 mounting in upon us over the fortifications.” This historic natural disaster caused two-thirds of the city to be swallowed into the Caribbean Sea, killing an estimated 2,000 people at the time of the earthquake, and another 2,000 from injury, disease, and extreme lawlessness in the days following. -

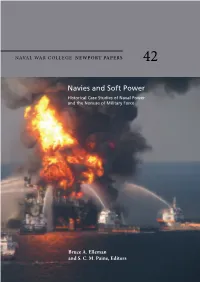

Navies and Soft Power Historical Case Studies of Naval Power and the Nonuse of Military Force NEWPORT PAPERS

NAVAL WAR COLLEGE NEWPORT PAPERS 42 NAVAL WAR COLLEGE WAR NAVAL Navies and Soft Power Historical Case Studies of Naval Power and the Nonuse of Military Force NEWPORT PAPERS NEWPORT 42 Bruce A. Elleman and S. C. M. Paine, Editors U.S. GOVERNMENT Cover OFFICIAL EDITION NOTICE The April 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil-rig fire—fighting the blaze and searching for survivors. U.S. Coast Guard photograph, available at “USGS Multimedia Gallery,” USGS: Science for a Changing World, gallery.usgs.gov/. Use of ISBN Prefix This is the Official U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identified to certify its au thenticity. ISBN 978-1-935352-33-4 (e-book ISBN 978-1-935352-34-1) is for this U.S. Government Printing Office Official Edition only. The Superinten- dent of Documents of the U.S. Government Printing Office requests that any reprinted edition clearly be labeled as a copy of the authentic work with a new ISBN. Legal Status and Use of Seals and Logos The logo of the U.S. Naval War College (NWC), Newport, Rhode Island, authenticates Navies and Soft Power: Historical Case Studies of Naval Power and the Nonuse of Military Force, edited by Bruce A. Elleman and S. C. M. Paine, as an official publica tion of the College. It is prohibited to use NWC’s logo on any republication of this book without the express, written permission of the Editor, Naval War College Press, or the editor’s designee. For Sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402-00001 ISBN 978-1-935352-33-4; e-book ISBN 978-1-935352-34-1 Navies and Soft Power Historical Case Studies of Naval Power and the Nonuse of Military Force Bruce A. -

Life Under the Jolly Roger: Reflections on Golden Age Piracy

praise for life under the jolly roger In the golden age of piracy thousands plied the seas in egalitarian and com- munal alternatives to the piratical age of gold. The last gasps of the hundreds who were hanged and the blood-curdling cries of the thousands traded as slaves inflated the speculative financial bubbles of empire putting an end to these Robin Hood’s of the deep seas. In addition to history Gabriel Kuhn’s radical piratology brings philosophy, ethnography, and cultural studies to the stark question of the time: which were the criminals—bankers and brokers or sailors and slaves? By so doing he supplies us with another case where the history isn’t dead, it’s not even past! Onwards to health-care by eye-patch, peg-leg, and hook! Peter Linebaugh, author of The London Hanged, co-author of The Many-Headed Hydra This vital book provides a crucial and hardheaded look at the history and mythology of pirates, neither the demonization of pirates as bloodthirsty thieves, nor their romanticization as radical communitarians, but rather a radical revisioning of who they were, and most importantly, what their stories mean for radical movements today. Derrick Jensen, author of A Language Older Than Words and Endgame Stripping the veneers of reactionary denigration and revolutionary romanti- cism alike from the realities of “golden age” piracy, Gabriel Kuhn reveals the sociopolitical potentials bound up in the pirates’ legacy better than anyone who has dealt with the topic to date. Life Under the Jolly Roger is important reading for anyone already fascinated by the phenomena of pirates and piracy. -

Pirate Articles and Their Society, 1660-1730

‘Piratical Schemes and Contracts’: Pirate Articles and their Society, 1660-1730 Submitted by Edward Theophilus Fox to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Maritime History In May 2013 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. 1 Abstract During the so-called ‘golden age’ of piracy that occurred in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans in the later seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, several thousands of men and a handful of women sailed aboard pirate ships. The narrative, operational techniques, and economic repercussions of the waves of piracy that threatened maritime trade during the ‘golden age’ have fascinated researchers, and so too has the social history of the people involved. Traditionally, the historiography of the social history of pirates has portrayed them as democratic and highly egalitarian bandits, divided their spoil fairly amongst their number, offered compensation for comrades injured in battle, and appointed their own officers by popular vote. They have been presented in contrast to the legitimate societies of Europe and America, and as revolutionaries, eschewing the unfair and harsh practices prevalent in legitimate maritime employment. This study, however, argues that the ‘revolutionary’ model of ‘golden age’ pirates is not an accurate reflection of reality. -

The Conquest of the Great Northwest; Being the Story of the Adventurers Of

THE CONQUEST OF.' THE GREAT NORTHWEST Collier's famous picture of Hudson's Last Hours. THE CONQUEST OF THE GREAT NORTHWEST Being the story of the ADVENTURERS OF ENGLAND kno'wn as THE HUDSON'S BA COMPANr. Ne'w pages in the history of the Canadian North'west and Western State; BY AGNES C. LAUT Author of "Lords of Me Nor/h," "Pathfinders of the West," et,. TWO VOLUMES IN ONE NEW YORK MOFFAT, YARD AND COMPANY MCMXI Copyright, 190$, by THE OUTXNG PUI3LISHING COMPANI1 Entered at Stationers' Hall, London, England AU Rit: Rmrved NEW EDITION IN ONE VOLUME Ocrosaz. 1911 Th5 OWNN I 100111 00. PIlls M011y, N. 4. TO G. C. L. and C M. A. CONTENTS OF VOLUME I PART I CHAPTER I PAGE Henry Hudson's First Voyage 3 CHAPTER II Hudson's Second Voyage CHAPTER III Hudson's Third Voyage CHAPTER IV Hudson's Fourth Voyage 49 CHAPTER V The Adventures of the Danes on Hudson BayJens Munck's Crew . 72 PART II CHAPTER VI Radisson, the Pathfinder, Discovers Hudson Bay and Founds the Company of Gentlemen Adventurers 97 CHAPTER VII The Adventures of the First VoyageRadisson Driven Back Organizes the Hudson's Bay Company and Writes his Journals of Four VoyagesThe Charter and the First ShareholdersAdventures of Radisson on the BayThe Coming of the French and the Quarrel. Contents CHAPTER VIII PAGE Gentlemen Adventurers ofEngland"LordS of the Outer MarchesTwo Centuriesof Company Rule Secret OathsThe Use ofWhiskeyThe Matrimonial OfficesThe Part the Company Played in theGame of International JugglingHow Tradeand Voyages 132 Were Conducted - CHAPTER IX If Radisson Can Do Without the Adventurers,the Adven- turers Cannot Do Without RadissonTheEruption of the French on the BayThe Beginningof the 162 Raiders . -

Seiter Timothy 2019URD.Pdf (3.760Mb)

KARANKAWAS: REEXAMINING TEXAS GULF COAST CANNIBALISM _______________ An Honors Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in Major _______________ By Timothy F. Seiter May, 2019 i KARANKAWAS: REEXAMINING TEXAS GULF COAST CANNIBALISM ______________________________ Timothy F. Seiter APPROVED: ______________________________ David Rainbow, Ph.D. Committee Chair ______________________________ Matthew J. Clavin, Ph.D. ______________________________ Andrew Joseph Pegoda, Ph.D. ______________________________ Mark A. Goldberg, Ph.D. ______________________________ Antonio D. Tillis, Ph.D. Dean, College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences Department of Hispanic Studies ii KARANKAWAS: REEXAMINING TEXAS GULF COAST CANNIBALISM _______________ An Abstract of An Honors Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in Major _______________ By Timothy F. Seiter May, 2019 iii ABSTRACT In 1688, the Karankawa Peoples abducted and adopted an eight-year-old Jean-Baptiste Talon from a French fort on the Texas Gulf Coast. Talon lived with these Native Americans for roughly two and a half years and related an eye-witness account of their cannibalism. Despite his testimony, some present-day scholars reject the Karankawas’ cannibalism. Because of an abundance of farfetched and grisly accounts made by Spanish priests, bellicose Texans, and sensationalist historians, these academics believe the custom of anthropophagy is a colonial fabrication. Facing a sea of outrageously prejudicial sources, these scholars have either drowned in them or found no reason to wade deeper. -

Navies and Soft Power

U.S. Naval War College U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons Newport Papers Special Collections 6-2015 Navies and Soft Power Bruce A. Elleman S.C.M. Paine Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/usnwc-newport-papers Recommended Citation Elleman, Bruce A. and Paine, S.C.M., "Navies and Soft Power" (2015). Newport Papers. 42. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/usnwc-newport-papers/42 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Newport Papers by an authorized administrator of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NAVAL WAR COLLEGE NEWPORT PAPERS 42 NAVAL WAR COLLEGE WAR NAVAL Navies and Soft Power Historical Case Studies of Naval Power and the Nonuse of Military Force NEWPORT PAPERS NEWPORT 42 Bruce A. Elleman and S. C. M. Paine, Editors U.S. GOVERNMENT Cover OFFICIAL EDITION NOTICE The April 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil-rig fire—fighting the blaze and searching for survivors. U.S. Coast Guard photograph, available at “USGS Multimedia Gallery,” USGS: Science for a Changing World, gallery.usgs.gov/. Use of ISBN Prefix This is the Official U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identified to certify its au thenticity. ISBN 978-1-935352-33-4 (e-book ISBN 978-1-935352-34-1) is for this U.S. Government Printing Office Official Edition only. The Superinten- dent of Documents of the U.S. -

La Piraterie En Guadeloupe Dans Les Années 1720 Kevin Porcher

Document generated on 09/28/2021 1:07 a.m. Bulletin de la Société d'Histoire de la Guadeloupe La piraterie en Guadeloupe dans les années 1720 Kevin Porcher Number 183, May–August 2019 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1064935ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1064935ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Société d'Histoire de la Guadeloupe ISSN 0583-8266 (print) 2276-1993 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Porcher, K. (2019). La piraterie en Guadeloupe dans les années 1720. Bulletin de la Société d'Histoire de la Guadeloupe, (183), 15–38. https://doi.org/10.7202/1064935ar Tous droits réservés © Société d'Histoire de la Guadeloupe, 2019 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ La piraterie en Guadeloupe dans les années 1720 Kevin PORCHER1 « Dans un travail honnête, il n’y a que de maigres rations, des salaires bas et un dur labeur. Chez nous, c’est l’abondance et la jouissance, le plaisir et les aises, la liberté et le pouvoir ; qui hésiterait à nous rejoindre quand tout ce que l’on risque, dans le pire des cas, c’est la triste allure que l’on a au bout d’une corde. -

The Literary Lineage of Charles Johnson's A

OF PYRATES AND PICAROS: THE LITERARY LINEAGE OF CHARLES JOHNSON’S A GENERAL HISTORY OF THE PYRATES _____________ A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English Sam Houston State University _____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts _____________ by Adam R. Morris December, 2017 OF PYRATES AND PICAROS: THE LITERARY LINEAGE OF CHARLES JOHNSON’S A GENERAL HISTORY OF THE PYRATES by Adam R. Morris ______________ APPROVED: Jason M. Payton, PhD Thesis Director Paul W. Child, PhD Committee Member Michael T. Demson, PhD Committee Member Abbey Zink, PhD Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated, first and foremost, to my parents, Bobby and Donna. Without the loving and stimulating environment in which you raised me and your continued support, none of my successes would have been possible. It is also dedicated to my former, current, and future students. You all are the very reason I do what I do. iii ABSTRACT Morris, Adam R., Of pyrates and picaros: the literary lineage of Charles Johnson’s A General History of the Pyrates. Master of Arts (English), December, 2017, Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, Texas. Charles Johnson’s A General History of the Pyrates is a text that exists at the nexus of Atlantic history, Atlantic literary studies, and oceanic studies. Though the study of Johnson’s work has most often been the province of historians, this thesis establishes the need to reconsider it as a literary artefact and explores its literary legacy and lineage through the use of material history and genre theories.