Steven Stucky

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coa-Program-For-Web.Pdf

HOUSTON GRAND OPERA AND SID MOORHEAD, CHAIRMAN WELCOME YOU TO THE TAMARA WILSON, LIVESTREAM HOST E. LOREN MEEKER, GUEST JUDGE FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 5, 2021 AT 7 P.M. BROADCAST LIVE FROM THE WORTHAM THEATER CENTER TEXT TO VOTE TEXT TO GIVE Text to vote for the Audience Choice Award. On page Support these remarkable artists who represent 9, you will see a number associated with each finalist. the future of opera. Text the number listed next to the finalist’s name to 713-538-2304 and your vote will be recorded. One Text HGO to 61094 to invest in the next generation vote per phone number will be registered. of soul-stirring inspiration on our stage! 2 WELCOME TO CONCERT OF ARIAS 2021 SID MOORHEAD Chairman A multi-generation Texan, Sid Moorhead is the owner of in HGO’s Overture group and Laureate Society, and he serves Moorhead’s Blueberry Farm, the first commercial blueberry on the company’s Special Events committee. farm in Texas. The farm, which has been in the Moorhead family for three generations, sits on 28 acres in Conroe and Sid was a computer analyst before taking over the family boasts over 9,000 blueberry plants. It is open seasonally, from business and embracing the art of berry farming. He loves to the end of May through mid-July, when people from far and travel—especially to Europe—and has joined the HGO Patrons wide (including many fellow opera-lovers and HGO staffers) visit on trips to Italy and Vienna. to pick berries. “It’s wonderful. -

American Academy of Arts and Letters

NEWS RELEASE American Academy of Arts and Letters Contact: Ardith Holmgrain 633 WEST 155 STREET, NEW YORK, NY 10032 [email protected] www.artsandletters.org (212) 368-5900 http://www.artsandletters.org/press_releases/2010music.php THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ARTS AND LETTERS ANNOUNCES 2010 MUSIC AWARD WINNERS Sixteen Composers Receive Awards Totaling $170,000 New York, March 4, 2010—The American Academy of Arts and Letters announced today the sixteen recipients of this year's awards in music, which total $170,000. The winners were selected by a committee of Academy members: Robert Beaser (chairman), Bernard Rands, Gunther Schuller, Steven Stucky, and Yehudi Wyner. The awards will be presented at the Academy's annual Ceremonial in May. Candidates for music awards are nominated by the 250 members of the Academy. ACADEMY AWARDS IN MUSIC Four composers will each receive a $7500 Academy Award in Music, which honors outstanding artistic achievement and acknowledges the composer who has arrived at his or her own voice. Each will receive an additional $7500 toward the recording of one work. The winners are Daniel Asia, David Felder, Pierre Jalbert, and James Primosch. WLADIMIR AND RHODA LAKOND AWARD The Wladimir and Rhoda Lakond award of $10,000 is given to a promising mid-career composer. This year the award will go to James Lee III. GODDARD LIEBERSON FELLOWSHIPS Two Goddard Lieberson fellowships of $15,000, endowed in 1978 by the CBS Foundation, are given to mid-career composers of exceptional gifts. This year they will go to Philippe Bodin and Aaron J. Travers. WALTER HINRICHSEN AWARD Paula Matthusen will receive the Walter Hinrichsen Award for the publication of a work by a gifted composer. -

In T H E W O R

I N T IN THE WORKS: FREE ORCHESTRA CONCERT Wednesday, August 5, 5:30pm | Santa Cruz Civic Auditorium You’ll find yourself at the very center of contemporary music-making with a special concert featuring new works by three young composers—Brendan Faegre, Takuma Itoh, H and Emily Praetorius—conducted in rotation by seven emerging conductors. All are studying in the prestigious Conductors/Composers Workshop. E W Don’t miss the excitement when the creative sparks fly! O R K S IN THE WORKS COMPOSERS BRENDAN FAEGRE TAKUMA ITOH EMILY PRAETORIUS Brendan Faegre is a Takuma Itoh spent his Emily Praetorius is composer, educator, early childhood in Japan a composer and b and l e ader, and before moving to Palo clarinetist from Ojai, percussionist whose Alto, California, where California. She holds music draws inspiration he grew up. His music a Master of Music from jazz and rock has been described as in composition from drumming, Hindustani “brashly youthful and Manhattan School of classical music, and fresh” (New York Times). Music (2014) and a contemporary concert Featured amongst one Bachelor of Music in music. Faegre’s works have been programmed of “100 Composers Under 40” on NPR Music, clarinet performance and composition from at festivals around the world, including Itoh has been the recipient of an award from the University of Redlands (2008). Praetorius Huddersfield (UK), Gaudeamus (NL), TRANSIT the American Academy of Arts and Letters; a has written for a variety of different instrumental Leuven (BE), Dark Music Days (IS), Beijing Charles Ives Scholarship; a Music Alive: New combinations, from clarinet duo with live Modern (CN), and Bang on a Can (US). -

German Jews in the United States: a Guide to Archival Collections

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 24 GERMAN JEWS IN THE UNITED STATES: AGUIDE TO ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS Contents INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 ABOUT THE EDITOR 6 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS (arranged alphabetically by state and then city) ALABAMA Montgomery 1. Alabama Department of Archives and History ................................ 7 ARIZONA Phoenix 2. Arizona Jewish Historical Society ........................................................ 8 ARKANSAS Little Rock 3. Arkansas History Commission and State Archives .......................... 9 CALIFORNIA Berkeley 4. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library, Archives .................................................................................................. 10 5. Judah L. Mages Museum: Western Jewish History Center ........... 14 Beverly Hills 6. Acad. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Margaret Herrick Library, Special Coll. ............................................................................ 16 Davis 7. University of California at Davis: Shields Library, Special Collections and Archives ..................................................................... 16 Long Beach 8. California State Library, Long Beach: Special Collections ............. 17 Los Angeles 9. John F. Kennedy Memorial Library: Special Collections ...............18 10. UCLA Film and Television Archive .................................................. 18 11. USC: Doheny Memorial Library, Lion Feuchtwanger Archive ................................................................................................... -

THE CLEVELAN ORCHESTRA California Masterwor S

����������������������� �������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������ �������������������������������������� �������� ������������������������������� ��������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������� �������������������� ������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������ ������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������� ����������������������������� ����� ������������������������������������������������ ���������������� ���������������������������������������� ��������������������������� ���������������������������������������� ��������� ������������������������������������� ���������� ��������������� ������������� ������ ������������� ��������� ������������� ������������������ ��������������� ����������� �������������������������������� ����������������� ����� �������� �������������� ��������� ���������������������� Welcome to the Cleveland Museum of Art The Cleveland Orchestra’s performances in the museum California Masterworks – Program 1 in May 2011 were a milestone event and, according to the Gartner Auditorium, The Cleveland Museum of Art Plain Dealer, among the year’s “high notes” in classical Wednesday evening, May 1, 2013, at 7:30 p.m. music. We are delighted to once again welcome The James Feddeck, conductor Cleveland Orchestra to the Cleveland Museum of Art as this groundbreaking collaboration between two of HENRY COWELL Sinfonietta -

Jeu De Timbres Steven Stucky

Jeu de timbres Steven Stucky (1949–2016) Written: 2003 Movements: One Style: Contemporary Duration: Four minutes Steven Stucky has an extensive catalogue of compositions ranging from large-scale orchestral works to a cappella miniatures for chorus. He is also active as a conductor, writer, lecturer, and teacher, and for 21 years he enjoyed a close partnership with the Los Angeles Philharmonic: In 1988 André Previn appointed him composer-in-residence of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, and later he became the orchestra’s consulting composer for new music, working closely with Esa-Pekka Salonen. Commissioned by the orchestra, his Second Concerto for Orchestra brought him the Pulitzer Prize in music in 2005. Steven Stucky taught at Cornell University from 1980 to 2014. He provides the following notes for Jeu de timbres: According to one rule of thumb for categorizing 20th-century music, works that emphasize thematic development and counterpoint are "German," while those that emphasize color, atmosphere and the beauty of individual harmonies are "French." Look at it closely enough, of course, and such a simplistic dichotomy fails right away—just think of the thematic development in Debussy, or the harmonic sorcery in Schoenberg or even (on a good day) Hindemith—but still it has its uses. If by "French" we mean music that follows Debussy's example in prizing the rich harmonic sonority or the delicate instrumental effect for its own sake (as opposed to valuing it mostly for its logical function in the musical grammar), then I am happily a composer of "French" music. Among my household gods are not only Debussy but also several other composers for whom sonority and color are not cosmetic frills but fundamental building blocks, including Stravinsky, Ravel, Varese, Messiaen, and Lutoslawski. -

Women Pioneers of American Music Program

Mimi Stillman, Artistic Director Women Pioneers of American Music The Americas Project Top l to r: Marion Bauer, Amy Beach, Ruth Crawford Seeger / Bottom l to r: Jennifer Higdon, Andrea Clearfield Sunday, January 24, 2016 at 3:00pm Field Concert Hall Curtis Institute of Music 1726 Locust Street, Philadelphia Charles Abramovic Mimi Stillman Nathan Vickery Sarah Shafer We are grateful to the William Penn Foundation and the Musical Fund Society of Philadelphia for their support of The Americas Project. ProgramProgram:: WoWoWomenWo men Pioneers of American Music Dolce Suono Ensemble: Sarah Shafer, soprano – Mimi Stillman, flute Nathan Vickery, cello – Charles Abramovic, piano Prelude and Fugue, Op. 43, for Flute and Piano Marion Bauer (1882-1955) Stillman, Abramovic Prelude for Piano in B Minor, Op. 15, No. 5 Marion Bauer Abramovic Two Pieces for Flute, Cello, and Piano, Op. 90 Amy Beach (1867-1944) Pastorale Caprice Stillman, Vickery, Abramovic Songs Jennifer Higdon (1962) Morning opens Breaking Threaded To Home Falling Deeper Shafer, Abramovic Spirit Island: Variations on a Dream for Flute, Cello, and Piano Andrea Clearfield (1960) I – II Stillman, Vickery, Abramovic INTERMISSION Prelude for Piano #6 Ruth Crawford Seeger (1901-1953) Study in Mixed Accents Abramovic Animal Folk Songs for Children Ruth Crawford Seeger Little Bird – Frog He Went A-Courtin' – My Horses Ain't Hungry – I Bought Me a Cat Shafer, Abramovic Romance for Violin and Piano, Op. 23 (arr. Stillman) Amy Beach June, from Four Songs, Op. 53, No. 3, for Voice, Violin, and -

Richard O'neill

Richard O’Neill 1276 Aikins Way Boulder, CO 80305 917.826.7041 [email protected] www.richard-oneill.com Education University of North Carolina School of the Arts 1997 High School Diploma University of Southern California, Thornton School of Music 2001 Bachelor of Music, magna cum laude The Juilliard School 2003 Master of Music The Juilliard School 2005 Artist Diploma Teaching University of Colorado, Boulder, College of Music 2020 - present Experience Artist in Residence, Takacs Quartet University of California Los Angeles, Herb Alpert School of Music 2007 - 2016 Lecturer of Viola University of Southern California, Thornton School of Music 2008 Viola Masterclasses Hello?! Orchestra (South Korea) 2012 - present Multicultural Youth Orchestra Founder, conductor and teacher Music Academy of the West, Santa Barbara 2014 - present Viola and Chamber Music Florida International University 2014 Viola Masterclass Brown University 2015 Viola Masterclass Hong Kong Academy of Performing Arts. 2016, 2018 Viola Masterclasses Scotia Festival 2017 Viola Masterclasses Asia Society, Hong Kong 2018 Viola and Chamber Music Masterclasses Mannes School of Music 2018 Viola Masterclass The Broad Stage, Santa Monica 2018 - 2019 Artist-in-residence, viola masterclasses, community events Affiliations Sejong Soloists 2001 - 2007 Principal Viola The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center 2003 - present CMS Two/Bowers YoungArtist from 2004-06 CREDIA International Artist Management 2004 - present Worldwide manager, based in South Korea Seattle Chamber Music Society -

Interview with David Alan Miller

The Classical Beat By Stephen Dankner INTERVIEW WITH MAESTRO DAVID ALAN MILLER Looking as if a few choice, slightly seedy blocks were snatched up from Greenwich Village and plunked down in Albany’s central city district, Lark Street is a fascinating, hip place. With a row of laid-back watering holes, eateries and latte dens, it was a good place to sit down for awhile with David Alan Miller, the conductor and Music Director of the Albany Symphony Orchestra over a cup of coffee. Miller is a young and energetic man, charming and likeable, irrepressible and ardent. He has the same messianic zeal that Leonard Bernstein had – a mission to convince you of his love for music – all kinds of it – and to prove to you, through the force of his high strung but always cheerful personality, that classical music is really important – it’s not just entertainment or an indulgence for an elite class of sedate listeners. No, it’s absolutely necessary. Listen to him for just a few minutes and you’ll be convinced; I have rarely encountered a more articulate spokesman for the cause. Miller has a talent for speaking off the cuff; his knowledge of music history and the full repertoire of classical music enable him to fire off facts, figures and opinions at his popular pre-concert conversations. It’s clear that audiences love him, judging by the filled seats for the talks one hour before the ASO concerts. Right about now he’s thinking seriously about next season. All orchestras have to schedule their programs at least a year in advance. -

Ojai North Music Festival

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS Thursday–Saturday, June 19–21, 2014 Hertz Hall Ojai North Music Festival Jeremy Denk Music Director, 2014 Ojai Music Festival Thomas W. Morris Artistic Director, Ojai Music Festival Matías Tarnopolsky Executive and Artistic Director, Cal Performances Robert Spano, conductor Storm Large, vocalist Timo Andres, piano Aubrey Allicock, bass-baritone Kim Josephson, baritone Dominic Armstrong, tenor Ashraf Sewailam, bass-baritone Rachel Calloway, mezzo-soprano Peabody Southwell, mezzo-soprano Keith Jameson, tenor Jennifer Zetlan, soprano The Knights Eric Jacobsen, conductor Brooklyn Rider Uri Caine Ensemble Hudson Shad Ojai Festival Singers Kevin Fox, conductor Ojai North is a co-production of the Ojai Music Festival and Cal Performances. Ojai North is made possible, in part, by Patron Sponsors Liz and Greg Lutz. Cal Performances’ – season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. CAL PERFORMANCES 13 FESTIVAL SCHEDULE Thursday–Saturday, June 19–21, 2014 Hertz Hall Ojai North Music Festival FESTIVAL SCHEDULE Thursday, June <D, =;<?, Cpm Welcome : Cal Performances Executive and Artistic Director Matías Tarnopolsky Concert: Bay Area première of The Classical Style: An Opera (of Sorts) plus Brooklyn Rider plays Haydn Brooklyn Rider Johnny Gandelsman, violin Colin Jacobsen, violin Nicholas Cords, viola Eric Jacobsen, cello The Knights Aubrey Allicock, bass-baritone Dominic Armstrong, tenor Rachel Calloway, mezzo-soprano Keith Jameson, tenor Kim Josephson, baritone Ashraf Sewailam, bass-baritone Peabody Southwell, mezzo-soprano Jennifer Zetlan, soprano Mary Birnbaum, director Robert Spano, conductor Friday, June =;, =;<?, A:>;pm Talk: The creative team of The Classical Style: An Opera (of Sorts) —Jeremy Denk, Steven Stucky, and Mary Birnbaum—in a conversation moderated by Matías Tarnopolsky PLAYBILL FESTIVAL SCHEDULE Cpm Concert: Second Bay Area performance of The Classical Style: An Opera (of Sorts) plus Brooklyn Rider plays Haydn Same performers as on Thursday evening. -

Berkeley Symphony 2012-13 Season

% #!"$ ! % ! ! $ Berkeley Symphony 2012-13 Season 5 Message from the Music Director 7 Message from the Executive Director 9 Board of Directors & Advisory Council 10 Orchestra 13 Program 15 Program Notes 29 Music Director: Joana Carneiro 31 Guest Artists 37 Berkeley Symphony 41 Music in the Schools 43 Under Construction 45 Young People’s Symphony Orchestra 47 Contributed Support 66 Advertiser Index Season Sponsors: Kathleen G. Henschel and Official Wine Sponsor of Berkeley Symphony: Presentation bouquets are graciously provided by Jutta’s Flowers, the official florist of Berkeley Symphony. Berkeley Symphony is a member of the League of American Orchestras and the Association of California Symphony Orchestras. No photographs or recordings of any part of tonight’s performance may be made without the written consent of the management of Berkeley Symphony. Program subject to change. Berkeley Symphony, 1942 University Ave., Ste. 207, Berkeley, CA 94704 510.841.2800 • Fax: 510.841.5422 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.berkeleysymphony.org To advertise: 510.652.3879 March 28, 2013 3 SAVE THE DATE Friday, May 10, 2013 The Claremont Hotel Berkeley Symphony’s Defiantly Original Benefit Gala Held at the historic Claremont Hotel, this year’s Gala promises to be an unforgettable event with new surprises and special guests! The night includes an elegant wine and hors d’oeuvres reception, world class cuisine, live music and entertainment, and exciting silent and live auctions with a bevy of unique items available. Be sure to keep an eye out for the 2013 Auction catalog to be available online soon! For more information, visit www.berkeleysymphony.org/support/ special-events. -

Orchestra Repertoire by Composer

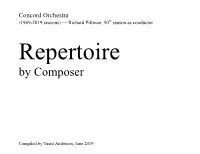

Concord Orchestra (1969-2019 seasons) –– Richard Pittman, 50th season as conductor by Composer Compiled by Grant Anderson, June 2019 1 Concord Orchestra Repertoire by Composer (1969-2019 seasons) — Richard Pittman, conductor Composer Composition Composed Soloists Groups Concert Adams John (1947 – ) Nixon in China: The Chairman Dances 1985 May 2000 Adams John (1947 – ) ShortA Short Ride in a Fast Machine (Fanfare for 1986 December 1990 Great Woods) Adams John (1947 – ) AShort Short Ride in a Fast Machine (Fanfare for 1986 December 2000 Great Woods) Adler Samuel (1928 – ) TheFlames Flames of Freedom: Ma’oz Tzur (Rock 1982 Lexington High School December 2015 of Ages), Mi y’mallel (Who Can Retell?) Women’s Chorus (Jason Iannuzzi) Albéniz Isaac (1860 – 1909) Suite española, Op. 47: Granada & Sevilla 1886 May 2016 Albert Stephen (1941 – 1992) River-Run: Rain Music, River's End 1984 October 1986 Alford, born Kenneth, born (1881 – 1945) Colonel Bogey March 1914 May 1994 Ricketts Frederick Anderson Leroy (1908 – 1975) Belle of the Ball 1951 May 1998 Anderson Leroy (1908 – 1975) Belle of the Ball 1951 July 1998 Anderson Leroy (1908 – 1975) Belle of the Ball 1951 May 2003 Anderson Leroy (1908 – 1975) Blue Tango 1951 May 1998 Anderson Leroy (1908 – 1975) Blue Tango 1951 May 2007 Anderson Leroy (1908 – 1975) Blue Tango 1951 May 2011 Anderson Leroy (1908 – 1975) BuglerA Bugler's Holiday 1954 Norman Plummer, April 1971 Thomas Taylor, Stanley Schultz trumpet Anderson Leroy (1908 – 1975) BuglerA Bugler's Holiday 1954f John Ossi, James May 1979 Dolham,