Growing up and Doing Time in an English Young Offender Institution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright Statement

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 2020 Black Male Representations in Non-Urban Settings in The UK Turner, Nathaniel http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/15777 University of Plymouth All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. Copyright Statement This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author's prior consent. BLACK MALE REPRESENTATIONS IN NON-URBAN SETTINGS IN THE UK by NATHANIEL TURNER A thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth in partial fulfilment for the degree of RESEARCH MASTERS School of Humanities and Performing Arts February 2020 ii Acknowledgements I would firstly like to thank Dr Victor Ramirez Ladron De Guevara (University of Plymouth) and Dr Lee Miller. Thank you for your guidance and support throughout this research process. I feel I have developed not only as a researcher but also as a person through this journey and I could not have better supervisors to steer me in the right direction when I lost my way. -

Instructions

MY DETAILS My Name: Jong B. Mobile No.: 0917-5877-393 Movie Library Count: 8,600 Titles / Movies Total Capacity : 36 TB Updated as of: December 30, 2014 Email Add.: jongb61yahoo.com Website: www.jongb11.weebly.com Sulit Acct.: www.jongb11.olx.ph Location Add.: Bago Bantay, QC. (Near SM North, LRT Roosevelt/Munoz Station & Congressional Drive Capacity & Loadable/Free Space Table Drive Capacity Loadable Space Est. No. of Movies/Titles 320 Gig 298 Gig 35+ Movies 500 Gig 462 Gig 70+ Movies 1 TB 931 Gig 120+ Movies 1.5 TB 1,396 Gig 210+ Movies 2 TB 1,860 Gig 300+ Movies 3 TB 2,740 Gig 410+ Movies 4 TB 3,640 Gig 510+ Movies Note: 1. 1st Come 1st Serve Policy 2. Number of Movies/Titles may vary depends on your selections 3. SD = Standard definition Instructions: 1. Please observe the Drive Capacity & Loadable/Free Space Table above 2. Mark your preferred titles with letter "X" only on the first column 3. Please do not make any modification on the list. 3. If you're done with your selections please email to [email protected] together with the confirmaton of your order. 4. Pls. refer to my location map under Contact Us of my website YOUR MOVIE SELECTIONS SUMMARY Categories No. of titles/items Total File Size Selected (In Gig.) Movies (2013 & Older) 0 0 2014 0 0 3D 0 0 Animations 0 0 Cartoon 0 0 TV Series 0 0 Korean Drama 0 0 Documentaries 0 0 Concerts 0 0 Entertainment 0 0 Music Video 0 0 HD Music 0 0 Sports 0 0 Adult 0 0 Tagalog 0 0 Must not be over than OVERALL TOTAL 0 0 the Loadable Space Other details: 1. -

New Bfi Research Reveals Representation of Black Actors in Uk Film Over Last 10 Years

NEW BFI RESEARCH REVEALS REPRESENTATION OF BLACK ACTORS IN UK FILM OVER LAST 10 YEARS 13% of UK films have a black actor in a leading role; 59% have no black actors in any role Noel Clarke is most prolific black actor in UK film, followed by Ashley Walters, Naomie Harris and Thandie Newton Decade sees little change in the number of roles for black actors; only 4 black actors feature in the list of the 100 most prolific actors 50% of all lead roles played by black actors are clustered in 47 films, potentially limiting opportunities for audiences to see diverse representation; these 47 films represent LESS than 5% of the total number of films Horror, drama and comedy films LEAST likely to cast black actors Crime, sci-fi and fantasy films MOST likely to cast black actors LONDON – Thursday 6 October, 2016: The BFI today announced ground-breaking new research that explores the representation of black actors in UK films over the last 10 years (January 2006 - August 2016) and reveals that out of the 1,172 UK films made and released in that period, 59% (691 films) did not feature any black actors in either lead or named roles1. The proportion of UK films2,3 which credited at least one black actor4 in a lead role was 13%, or 157 films in total. The new research provides an early indicator of what is set to be the most comprehensive set of data about UK films from 1911 to the present day – the BFI Filmography, launching in 2017. -

Members Newsletter 2014 Autumn

the autumn newsletter 2014 for our members, our patients and the public ‘The Unsaid’, collage & ink pen, Size 25.4x17.8cm, by Natalie Abadzis what’s in this edition? a new name for one of patient stories pledging our support Camden’s services our up and coming annual Tottenham thinking space bid for better 2014 general meeting project The Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust contents our artwork angela and paul’s chosen by young tip-top welcome message people, for young organisation joins people 100 club page 2 page 3 page 4 page 4 patient stories i dream in autism our information teaching staff and london skills trainer complete UEL triathlon scheme page 5 page 6 page 7 page 7 time to change anxiety: tend it like portman clinic, improving our and Tottenham Beckham and bid young people accommodation, thinking space for better 2014 meet Akala patient poems page 8 page 9 page 10 pages 11 and 12 our artwork Natalie Abadzis is an artist, teacher and life archivist based in London. Her artworks span drawing, collage, and photography. She has also written and illustrated three craft books with Scholastic UK publishing. Natalie’s exhibition of new art opens at our artspace on 17 October 2014. Please join us at the Tavistock Centre to enjoy Natalie’s playful and exuberant work, for more information and images you can visit: natalie-abadzis.tumblr.com and www.natalieabadzis.com/ SAVE THE DATE: Wednesday 22 October This year’s Annual General Meeting (AGM) is on Wednesday 22 October and will feature a keynote presentation from one of our award winning services: City and Hackney Primary Care Psychotherapy Consultation Service (PCPCS). -

Title ID Titlename D0043 DEVIL's ADVOCATE D0044 a SIMPLE

Title ID TitleName D0043 DEVIL'S ADVOCATE D0044 A SIMPLE PLAN D0059 MERCURY RISING D0062 THE NEGOTIATOR D0067 THERES SOMETHING ABOUT MARY D0070 A CIVIL ACTION D0077 CAGE SNAKE EYES D0080 MIDNIGHT RUN D0081 RAISING ARIZONA D0084 HOME FRIES D0089 SOUTH PARK 5 D0090 SOUTH PARK VOLUME 6 D0093 THUNDERBALL (JAMES BOND 007) D0097 VERY BAD THINGS D0104 WHY DO FOOLS FALL IN LOVE D0111 THE GENERALS DAUGHER D0113 THE IDOLMAKER D0115 SCARFACE D0122 WILD THINGS D0147 BOWFINGER D0153 THE BLAIR WITCH PROJECT D0165 THE MESSENGER D0171 FOR LOVE OF THE GAME D0175 ROGUE TRADER D0183 LAKE PLACID D0189 THE WORLD IS NOT ENOUGH D0194 THE BACHELOR D0203 DR NO D0204 THE GREEN MILE D0211 SNOW FALLING ON CEDARS D0228 CHASING AMY D0229 ANIMAL ROOM D0249 BREAKFAST OF CHAMPIONS D0278 WAG THE DOG D0279 BULLITT D0286 OUT OF JUSTICE D0292 THE SPECIALIST D0297 UNDER SIEGE 2 D0306 PRIVATE BENJAMIN D0315 COBRA D0329 FINAL DESTINATION D0341 CHARLIE'S ANGELS D0352 THE REPLACEMENTS D0357 G.I. JANE D0365 GODZILLA D0366 THE GHOST AND THE DARKNESS D0373 STREET FIGHTER D0384 THE PERFECT STORM D0390 BLACK AND WHITE D0391 BLUES BROTHERS 2000 D0393 WAKING THE DEAD D0404 MORTAL KOMBAT ANNIHILATION D0415 LETHAL WEAPON 4 D0418 LETHAL WEAPON 2 D0420 APOLLO 13 D0423 DIAMONDS ARE FOREVER (JAMES BOND 007) D0427 RED CORNER D0447 UNDER SUSPICION D0453 ANIMAL FACTORY D0454 WHAT LIES BENEATH D0457 GET CARTER D0461 CECIL B.DEMENTED D0466 WHERE THE MONEY IS D0470 WAY OF THE GUN D0473 ME,MYSELF & IRENE D0475 WHIPPED D0478 AN AFFAIR OF LOVE D0481 RED LETTERS D0494 LUCKY NUMBERS D0495 WONDER BOYS -

News Release. 2016 Toronto International Film Festival Unveils Its

July 26, 2016 .NEWS RELEASE. 2016 TORONTO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL UNVEILS ITS FIRST SLATE OF GALAS AND SPECIAL PRESENTATIONS Featuring World Premieres from filmmakers including Oliver Stone, Mira Nair, Ewan McGregor, Konkona Sensharma, Lone Scherfig, Raja Amari, Jonathan Demme, Baltasar Kormákur, Amma Asante, Christopher Guest, Feng Xiaogang, Rob Reiner, J.A. Bayona, Arnaud des Pallières, Kiyoshi Kurosawa and many more TORONTO — Piers Handling, CEO and Director of TIFF, and Cameron Bailey, Artistic Director of the Toronto International Film Festival, announced the first round of titles premiering in the Gala and Special Presentations programmes of the 41st Toronto International Film Festival®. Of the 18 Galas and 49 Special Presentations announced, this initial lineup includes films from such celebrated directors as Werner Herzog, Denis Villeneuve, Jim Jarmusch, Mia Hansen-Løve, Rebecca Zlotowski, Tom Ford, François Ozon, Andrea Arnold, Maren Ade, Park Chan-wook, Kim Jee woon, Kenneth Lonergan, Antoine Fuqua, Damien Chazelle, Pablo Larraín, and Paul Verhoeven. “Revealing the first round of films offers a highly anticipated glimpse into the Festival’s lineup this year,” said Handling. “Bold and adventuresome work by established and emerging filmmakers from Canada, France, South Africa, Ireland, the UK, Australia, USA, South Korea, Iceland, Germany, Denmark, Chile, India, and China will illuminate Toronto screens and red carpets over another remarkable 11 days this September.” “The global voices, transformative stories and diverse perspectives of these films capture the cinematic climate of today,” said Bailey. “New films featuring cinema’s brightest talents promise to captivate and entertain the world’s film community and audiences alike.” The 41st Toronto International Film Festival runs from September 8 to 18, 2016. -

Damian Jones Producer

Damian Jones Producer Agents Natasha Galloway Associate Agent Talia Tobias [email protected] + 44 (0) 20 3214 0860 Credits Film Production Company Notes UNTITLED ROM COM Searchlight / BBC / BFI Dir: Raine Ann Miller 2021 UNTITLED MURDER MYSTERY Searchlight Dir: Tom George (with Saoirse 2020 Ronan, Sam Rockwell and David Oyelowo) BRIAN & CHARLES Film 4 / BFI As: Executive Producer. 2020 BOXING DAY Warner Bro.s / Film 4 / BFI (with Aml Ameen) 2020 THIS NAN'S LIFE Warners Bros Pictures / Catherine Tate 2019 Great Point Media BLUE STORY Paramount/BBC Rapman 2019 AMULET EdgeBox/AMP As: Executive Producer. Dir: 2019 Romola Garai. Starring: Imelda Staunton. MONDAY Farlo House/Protagonist As: Producer. Dir: Argyris 2019 Papadimitropoulos. Starring: Sebastian Stan, Denise Gough. GREED Sony/Film4 As: Producer. Dir: Michael 2019 Winterbottom. Starring: Steve Coogan, Isla Fisher, Asa Butterfield United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes GOODBYE CHRISTOPHER ROBIN DJ Films/Fox Searchlight As: Producer 2016 Dir: Simon Curtis (with Margot Robbie, Domhnall Gleeson, Kelly Macdonald) ABSOLUTELY FABULOUS: THE DJ Films/Fox As Producer MOVIE Searchlight/BBC Films Dir: Mandie Fletcher 2015 (With Jennifer Saunders, Joanna Lumley, Jane Horrocks) A STREETCAT NAMED BOB Prescience / Shooting As Executive Producer 2015 Script Films (With Ruta Gedmintas, Luke Treadaway) THE RECEPTIONIST Dark Horse Image / As Executive Producer 2015 Uncanny Films Dir: Jenny Lu Prods: Peter J Kirby, Chiou Zi Ning, Shuang Teng (With Teresa Daley, Chen Shiang Chyi, Josh Whitehouse) DAD'S ARMY Universal / Screen Yorkshire Dir: Oliver Parker 2015 (With Catherine Zeta-Jones, Bill Nighy, Toby Jones) LADY IN THE VAN Tristar / BBC Dir: Nicholas Hytner 2015 Written by Alan Bennett (With Maggie Smith, Alex Jennings) POWDER ROOM DJ Films / Universal Dir. -

(IN)VISIBLE ENTREPRENEURS: CREATIVE ENTERPRISE in the URBAN MUSIC ECONOMY Joy White

(IN)VISIBLE ENTREPRENEURS: CREATIVE ENTERPRISE IN THE URBAN MUSIC ECONOMY Joy White A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Greenwich for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2014 DECLARATION “I certify that this work has not been accepted in substance for any degree, and is not concurrently being submitted for any degree other than that of Doctor of Philosophy being studied at the University of Greenwich. I also declare that this work is the result of my own investigations except where otherwise identified by references and that I have not plagiarised another’s work”. Signed: Signed: Dated: June 2014 ! "" ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge the unwavering support of my supervisors, Dr Gauti Sigthorsson and Dr Stephen Kennedy. In particular, for letting me know that this research project had value and that it was a worthwhile object of study. Also, Dawn, Maxine, Dean and Alvin who proofread the final drafts - without complaining and resisted the temptation to ask whether I’d finished it yet. Lindsey and Gamze, for their encouragement and support throughout all of the economic and social ups and downs during the life of this project. My mum, Ivaline White whose three-week journey in 1954 from Jamaica to London provided the foundation, and gave me the courage, to start and to finish this. My daughter Karis, who once she had embraced her position as a ‘PhD orphan’, grew up with the project, accompanied me while I presented at an academic conference in Turkey, matured and evolved into an able research assistant, drawing my attention to significant events, music and debates. -

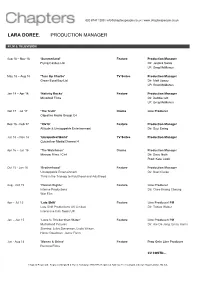

Lara Doree. Production Manager

020 8747 1203 | [email protected] | www.chapterspeople.co.uk LARA DOREE. PRODUCTION MANAGER FILM & TELEVISION Aug 18 – Nov 18 ‘Summerland’ Feature Production Manager Flying Castles Ltd Dir: Jessica Swale LP: Greg McManus May 18 – Aug 18 ‘Turn Up Charlie’ TV Series Production Manager Green Eyed Boy Ltd Dir: Matt Lipsey LP: Greg McManus Jan 18 – Apr 18 ‘Nativity Rocks’ Feature Production Manager Mirrorball Films Dir: Debbie Isitt LP: Greg McManus Apr 17 – Jul 17 ‘The Truth’ Drama Line Producer Objective Media Group/ C4 Dec 16 - Feb 17 ‘10x10’ Feature Production Manager Altitude & Unstoppable Entertainment Dir: Suzi Ewing Jun 16 – Nov 16 ‘Unreported World’ TV Series Production Manager Quicksilver Media/Channel 4 Apr 16 – Jun 16 ‘The Watchman’ Drama Production Manager Minnow Films / Ch4 Dir: Dave Nath Prod: Kate Cook Oct 15 - Jan 16 ‘Brotherhood’ Feature Production Manager Unstoppable Entertainment Dir: Noel Clarke Third in the Triology to Kidulthood and Adulthood Aug - Oct 15 ‘Human Rights’ Feature Line Producer Intense Productions Dir: Chee Keong Cheung War Film Apr – Jul 15 ‘Late Shift’ Feature Line Producer/ PM Late Shift Productions UK Limited Dir: Tobias Weber Interactive Film Swiss UK Jan – Apr 15 ‘Love Is Thicker than Water’ Feature Line Producer/ PM Mulholland Pictures Dir: Ate De Jong, Emily Harris Starring: Juliet Stevenson, Lydia Wilson, Henry Goodman, Jonny Flynn Jun - Aug 14 ‘Money & Grime’ Feature Prep Only Line Producer Running Films CV CONTD… Chapters People Ltd. Registered England & Wales. Company: 07003175. Registered Address: The Courtyard, 4 Evelyn Road, London, W4 5JL. 020 8747 1203 | [email protected] | www.chapterspeople.co.uk Aug - Oct 14 ‘Deny Everything’ Feature Line Producer Reality Shift Productions Director: Michael Eden Jul 14/ Dec 15 ‘Falling Piano’ Art Piece Line Producer/ PM Arts Council Project/ Catherine Yass Aug-14 ‘Dumpee’ Feature PM (extended shoot) Dumpee Ltd Dir: Sasha Collington. -

Sket Press Pack

PRESENTS From GUNSLINGER, the producers of ANUVAHOOD and SHANK, A GUNSLINGER FILMS Production A GATEWAY FILMS Co-Production in association with AV PICTURES, CREATIVITY MEDIA and AQUARIUM PRESS PACK Released Nationwide on: 28TH OCTOBER 2011 Running Time: 83 Mins Certificate: TBC FOR FURTHER INFORMATION, INTERVIEW REQUESTS AND SCREENINGS, PLEASE CONTACT: Monica Macasieb – [email protected] – Tel: 020 7243 4300 Tracey Zetter – [email protected] – Tel: 07980 611312 FOR ONLINE QUERIES, PLEASE CONTACT: Jamie Danan – [email protected] – Tel: 07885 670 294 www.revolvergroup.com www.sketmovie.com The rise in the proliferation of girl gangs is symptomatic of some of the major problems facing modern society. SKET takes a controversial look at this phenomenon sweeping the streets of Britain. ‘SKET’ is a derogatory term, defined in urban street culture as a woman with no regard or care for morals or dignity. This fast paced retribution thriller provides a hard hitting front row seat of UK girl gangs and the adrenaline fuelled criminality they run on. There is a distinct lack of public knowledge about female gang culture, which results in a high level of fascination – yet not one film has dared to explore it – until now. I met with various members of male and female gangs in order to learn why young women were now, more than ever, adopting aggressive male behaviour. The more I immersed myself in their ideologies the more I realised that their shift in behaviour could be explained as progressive adaptation, a theme that is at the very heart of ‘Sket’: society is changing, and girls and women must change with it in order to survive. -

Black-British : Regards Masculins Sur Des Destins De Femmes (Burning an Illusion, 1981 ; Elphida, 1987 ; Babymother, 1998)

Genre en séries Cinéma, télévision, médias 8 | 2018 Femmes et féminité en évolution dans le cinéma et les séries anglophones Les héroïnes noires du cinéma black-british : regards masculins sur des destins de femmes (Burning an Illusion, 1981 ; Elphida, 1987 ; Babymother, 1998) Émilie Herbert Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ges/509 DOI : 10.4000/ges.509 ISSN : 2431-6563 Éditeur Presses universitaires de Bordeaux Référence électronique Émilie Herbert, « Les héroïnes noires du cinéma black-british : regards masculins sur des destins de femmes (Burning an Illusion, 1981 ; Elphida, 1987 ; Babymother, 1998) », Genre en séries [En ligne], 8 | 2018, mis en ligne le 01 décembre 2018, consulté le 18 février 2021. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/ges/509 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ges.509 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 18 février 2021. La revue Genre en séries est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Les héroïnes noires du cinéma black-british : regards masculins sur des desti... 1 Les héroïnes noires du cinéma black-british : regards masculins sur des destins de femmes (Burning an Illusion, 1981 ; Elphida, 1987 ; Babymother, 1998) Émilie Herbert 1 Lors du référendum sur le retrait du Royaume-Uni de l’Union Européenne en juin 2016, une majorité de citoyen.ne.s britanniques votait pour le Brexit. Si certains “brexiters” voient dans le rejet de l’Europe la possibilité de nouer des liens – notamment économiques – plus étroits avec les pays du Commonwealth (Howell, 2016), ce vote semble néanmoins révéler une vision nationaliste et xénophobe d’une britannicité tournant le dos au multiculturalisme qui l’a pendant longtemps définie (MacShane, 2017). -

Nominees Are Unveiled for the Orange Wednesdays Rising Star Award in 2012

NOMINEES ARE UNVEILED FOR THE ORANGE WEDNESDAYS RISING STAR AWARD IN 2012 • The Orange Wednesdays Rising Star Award is the only award at the Orange British Academy Film Awards to be voted for by the British public • Orange Wednesdays customers have selected the shortlist of five from a long list of eight determined by the award jurors • The winner will be announced at the awards on 12 February 2012 • Previous winners include: James McAvoy, Eva Green, Shia LaBeouf, Noel Clarke, Kristen Stewart and Tom Hardy London 11 January 2012. Today at BAFTA’s headquarters, Pippa Harris, award jury chair, Deputy Chair of BAFTA’s Film Committee and producing partner of Sam Mendes, announced the hotly anticipated nominees for the Orange Wednesdays Rising Star Award 2012 as selected by Orange Wednesdays customers from a long list of eight. The nominations recognise five international actors and actresses whose talent has captured the imagination of the British public. The nominees are: • ADAM DEACON - Hackney-born Adam rose to fame in Noel Clarke’s KIDULTHOOD, before reprising the role in the follow-up ADULTHOOD and again working with Clarke in 4321 . Adam then went onto mark his own mark on the film industry by co-writing, directing and starring in Brit comedy and box office success ANUVAHOOD. • CHRIS HEMSWORTH - Australian actor Chris became an overnight success after landing the title role in film version of the Marvel comic THOR and he will reprise the role in THE AVENGERS next year. Chris is next starring in SNOW WHITE AND THE HUNTSMAN opposite Kirsten Stewart and Charlize Theron and will play Formula One driver James Hunt in Ron Howard’s RUSH.