Changes in the Location and Compostion of Major Shopping

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

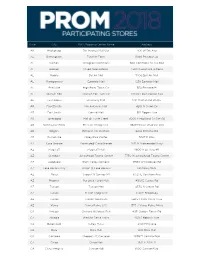

Prom 2018 Event Store List 1.17.18

State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address AK Anchorage 5th Avenue Mall-Sur 406 W 5th Ave AL Birmingham Tutwiler Farm 5060 Pinnacle Sq AL Dothan Wiregrass Commons 900 Commons Dr Ste 900 AL Hoover Riverchase Galleria 2300 Riverchase Galleria AL Mobile Bel Air Mall 3400 Bell Air Mall AL Montgomery Eastdale Mall 1236 Eastdale Mall AL Prattville High Point Town Ctr 550 Pinnacle Pl AL Spanish Fort Spanish Fort Twn Ctr 22500 Town Center Ave AL Tuscaloosa University Mall 1701 Macfarland Blvd E AR Fayetteville Nw Arkansas Mall 4201 N Shiloh Dr AR Fort Smith Central Mall 5111 Rogers Ave AR Jonesboro Mall @ Turtle Creek 3000 E Highland Dr Ste 516 AR North Little Rock Mc Cain Shopg Cntr 3929 Mccain Blvd Ste 500 AR Rogers Pinnacle Hlls Promde 2202 Bellview Rd AR Russellville Valley Park Center 3057 E Main AZ Casa Grande Promnde@ Casa Grande 1041 N Promenade Pkwy AZ Flagstaff Flagstaff Mall 4600 N Us Hwy 89 AZ Glendale Arrowhead Towne Center 7750 W Arrowhead Towne Center AZ Goodyear Palm Valley Cornerst 13333 W Mcdowell Rd AZ Lake Havasu City Shops @ Lake Havasu 5651 Hwy 95 N AZ Mesa Superst'N Springs Ml 6525 E Southern Ave AZ Phoenix Paradise Valley Mall 4510 E Cactus Rd AZ Tucson Tucson Mall 4530 N Oracle Rd AZ Tucson El Con Shpg Cntr 3501 E Broadway AZ Tucson Tucson Spectrum 5265 S Calle Santa Cruz AZ Yuma Yuma Palms S/C 1375 S Yuma Palms Pkwy CA Antioch Orchard @Slatten Rch 4951 Slatten Ranch Rd CA Arcadia Westfld Santa Anita 400 S Baldwin Ave CA Bakersfield Valley Plaza 2501 Ming Ave CA Brea Brea Mall 400 Brea Mall CA Carlsbad Shoppes At Carlsbad -

State City Shopping Center Address

State City Shopping Center Address AK ANCHORAGE 5TH AVENUE MALL SUR 406 W 5TH AVE AL FULTONDALE PROMENADE FULTONDALE 3363 LOWERY PKWY AL HOOVER RIVERCHASE GALLERIA 2300 RIVERCHASE GALLERIA AL MOBILE BEL AIR MALL 3400 BELL AIR MALL AR FAYETTEVILLE NW ARKANSAS MALL 4201 N SHILOH DR AR FORT SMITH CENTRAL MALL 5111 ROGERS AVE AR JONESBORO MALL @ TURTLE CREEK 3000 E HIGHLAND DR STE 516 AR LITTLE ROCK SHACKLEFORD CROSSING 2600 S SHACKLEFORD RD AR NORTH LITTLE ROCK MC CAIN SHOPG CNTR 3929 MCCAIN BLVD STE 500 AR ROGERS PINNACLE HLLS PROMDE 2202 BELLVIEW RD AZ CHANDLER MILL CROSSING 2180 S GILBERT RD AZ FLAGSTAFF FLAGSTAFF MALL 4600 N US HWY 89 AZ GLENDALE ARROWHEAD TOWNE CTR 7750 W ARROWHEAD TOWNE CENTER AZ GOODYEAR PALM VALLEY CORNERST 13333 W MCDOWELL RD AZ LAKE HAVASU CITY SHOPS @ LAKE HAVASU 5651 HWY 95 N AZ MESA SUPERST'N SPRINGS ML 6525 E SOUTHERN AVE AZ NOGALES MARIPOSA WEST PLAZA 220 W MARIPOSA RD AZ PHOENIX AHWATUKEE FOOTHILLS 5050 E RAY RD AZ PHOENIX CHRISTOWN SPECTRUM 1727 W BETHANY HOME RD AZ PHOENIX PARADISE VALLEY MALL 4510 E CACTUS RD AZ TEMPE TEMPE MARKETPLACE 1900 E RIO SALADO PKWY STE 140 AZ TUCSON EL CON SHPG CNTR 3501 E BROADWAY AZ TUCSON TUCSON MALL 4530 N ORACLE RD AZ TUCSON TUCSON SPECTRUM 5265 S CALLE SANTA CRUZ AZ YUMA YUMA PALMS S C 1375 S YUMA PALMS PKWY CA ANTIOCH ORCHARD @SLATTEN RCH 4951 SLATTEN RANCH RD CA ARCADIA WESTFLD SANTA ANITA 400 S BALDWIN AVE CA BAKERSFIELD VALLEY PLAZA 2501 MING AVE CA BREA BREA MALL 400 BREA MALL CA CARLSBAD PLAZA CAMINO REAL 2555 EL CAMINO REAL CA CARSON SOUTHBAY PAV @CARSON 20700 AVALON -

2019 Property Portfolio Simon Malls®

The Shops at Clearfork Denver Premium Outlets® The Colonnade Outlets at Sawgrass Mills® 2019 PROPERTY PORTFOLIO SIMON MALLS® LOCATION GLA IN SQ. FT. MAJOR RETAILERS CONTACTS PROPERTY NAME 2 THE SIMON EXPERIENCE WHERE BRANDS & COMMUNITIES COME TOGETHER SIMON MALLS® LOCATION GLA IN SQ. FT. MAJOR RETAILERS CONTACTS PROPERTY NAME 2 ABOUT SIMON Simon® is a global leader in retail real estate ownership, management, and development and an S&P 100 company (Simon Property Group, NYSE:SPG). Our industry-leading retail properties and investments across North America, Europe, and Asia provide shopping experiences for millions of consumers every day and generate billions in annual sales. For more information, visit simon.com. · Information as of 12/16/2019 3 SIMON MALLS® LOCATION GLA IN SQ. FT. MAJOR RETAILERS CONTACTS PROPERTY NAME More than real estate, we are a company of experiences. For our guests, we provide distinctive shopping, dining, and entertainment. For our retailers, we offer the unique opportunity to thrive in the best retail real estate in the best markets. From new projects and redevelopments to acquisitions and mergers, we are continuously evaluating our portfolio to enhance the Simon experience—places where people choose to shop and retailers want to be. 4 LOCATION GLA IN SQ. FT. MAJOR RETAILERS CONTACTS PROPERTY NAME WE DELIVER: SCALE A global leader in the ownership of premier shopping, dining, entertainment, and mixed-use destinations, including Simon Malls®, Simon Premium Outlets®, and The Mills® QUALITY Iconic, irreplaceable properties in great locations INVESTMENT Active portfolio management increases productivity and returns GROWTH Core business and strategic acquisitions drive performance EXPERIENCE Decades of expertise in development, ownership, and management That’s the advantage of leasing with Simon. -

Denny's 5700 W. Kellogg Drive Wichita, KS 67209

5700 W Kellogg Drive Wichita, KS 67209 OFFERING MEMORANDUM ™ Exclusively Listed By Chuck Evans Keegan Mulcahy Kyle Matthews Senior Associate Associate Broker of Record [email protected] [email protected] LIC #77576 (KS) DIR: (310) 919-5841 DIR: (310) 955-1782 MOB: (925) 323-2263 MOB: (415) 847-5588 LIC #01963473 (CA) LIC #02067187 (CA) 2 | DENNY’S Executive Overview Investment Highlights • Long Operating History - Denny’s has operated in this location since 1973 • Two (2) Five (5) Year Options • Hedge Against Inflation - 5% Rental increases in options • Below market rent • Experienced Operator - Strong history of success • Strong retail corridor with national tenants such as Walmart, Best Buy, Burlington, Boot Barn, Texas Roadhouse, Golden Corral, Cracker Barrel and many more. • Across the street from Dwight D. Eisenhower International Airport, which has approximately 1,600,000 passengers per year. Wichita, KS | 3 Financial Overview EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Property Name Denny’s 5700 W Kellogg Drive FINANCIAL OVERVIEW Address Wichita, KS 67209 Year Built 1973 APN 138-27-0-14-04-002.00 GLA ±3,510 LIST PRICE CAP RATE TERM REMAINING Lot Size ±0.90 Acres $805,714 7.00% ±4.75 Years TENANT SUMMARY ANNUALIZED OPERATING DATA Tenant Trade Name Denny’s Type of Ownership Fee Simple Monthly Annual Lease Guarantor Franchisee Rent/SF Cap Rate Rent Rent Lease Type NNN Current $4,700.00 $56,400 $16.07 7.00% Roof & Structure Tenant Responsible Option 1 $4,935.00 $59,220 $16.87 7.35% Original Lease Term 10 Years Option 2 $5,181.75 $62,181 $17.72 7.72% Rent Commencement Date 6/28/2013 Lease Expiration Date 6/27/2023 Term Remaining ±4.75 Years Increases 5% Every 5 Years Options Two, 5-Year Options 4 | DENNY’S Tenant Overview Parent Company Trade Name Headquartered No. -

New Natural Grocers

New natural grocers metro area location ACTUAL STORE New 15 year net lease For more info on this opportunity please contact: RICK SANNER BOB SANNER [email protected] | (415) 274-2709 [email protected] | (415) 274-2717 rental increases CA BRE# 01792433 CA BRE# 00869657 JOHN ANDREINI CHRIS KOSTANECKI $85K Average incomes [email protected] | (415) 274-2715 [email protected] | (415) 274-2701 CA BRE# 01440360 CA BRE# 01002010 1401 North Maize Road, Wichita, KS 67212 In conjunction with KS Licensed Broker: Mark McPherson, Equity Ventures Commercial, Inc Capital Pacific collaborates. Click here to meet the rest of our San Francisco team. (720) 502-5190 | [email protected] BRAND NEW NATURAL GROCERS IN WICHITA, THE Investment Highlights LARGEST CITY IN KANSAS PRICE: $4,828,430 RENTABLE SF . 15,000 SF CAP: 6.25% LAND AREA . 1.58 Acres LEASE TYPE . NNN New 15 year net lease with rental increases, high growth public company tenant Freestanding site with additional signage and access on highly trafficked Maize Road $85,000 average household incomes within a one mile radius February 24, 2015, grand opening ACTUAL STORE NATUral GROCERS | 2 Income & Expense PRICE $4,828,430 Capitalization Rate: 6.25% Total Rentable Area (SF): 15,000 Lot Size (Acres): 1.58 STABILIZED INCOME Per Square Foot Scheduled Rent $20.12 $301,777 LESS Per Square Foot Taxes Tenant Expense $0.00 Insurance Tenant Expense $0.00 EQUALS NET OPERATING INCOME $301,777 The landlord is responsible for structure (but not roof). All other expenses (including roof) are a tenant responsibility. The store will open February 24, 2015. -

In the Superior Court of the State of Delaware Simon

EFiled: Jun 02 2020 05:08PM EDT Transaction ID 65668754 Case No. N20C-06-034 EMD CCLD IN THE SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE SIMON PROPERTY GROUP, L.P., ) on behalf of itself and its affiliated ) landlord entities, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) C.A. No. (CCLD) ) THE GAP, INC., OLD NAVY, LLC, ) INTERMIX HOLDCO, INC., ) BANANA REPUBLIC, LLC, AND ) ATHLETA LLC, ) ) Defendants. ) COMPLAINT Plaintiff Simon Property Group, L.P. (“Simon”), on behalf of itself and as assignee of its various landlord entities (“Simon Landlords”), by and through its undersigned counsel, and as for its Complaint against The Gap, Inc., Old Navy, LLC, Intermix HoldCo, Inc., Banana Republic, LLC, and Athleta LLC (collectively, “Defendants” or “The Gap Entities”), alleges and states as follows: NATURE OF THE ACTION 1. Simon seeks monetary damages from The Gap Entities for failure to pay more than $65.9 million in rent and other charges due and owing under certain retail Leases (defined below) plus attorneys’ fees and expenses incurred in connection with this suit. 2. The Gap Entities are in default on each of the Leases for failure to pay rent for April, May and June, 2020. As of the date of this filing (June 2, 2020), there is due and owing approximately $65.9 million in unpaid rent to each of the Landlord entities. The amounts due and owing will continue to accrue each month, with interest, and The Gap Entities are expected to fall even further behind in rent and other charges due to be paid to the Simon Landlords. PARTIES 3. Simon, a Delaware limited partnership, is the principal operating partnership for Simon Property Group, Inc., a publicly-held Delaware corporation and Simon’s sole general partner. -

Target Anchored Pad Sites Maple Street West of Ridge Road Wichita, KS

Target Anchored Pad Sites Maple Street West of Ridge Road Wichita, KS Presented By: InSite Real Estate Group Parcel 4 Parcel 3 0.91 Acres 0.86 Acres Real � SiteEstate � Group Aerial Photo Parcel 4 Parcel 3 Parcel 2 .91 Acres .86 Acres SOLD!1.01 Acres Real � SiteEstate � Group Project Summary The site consists of (2) two retail/restaurant pad sites located in front of a new Target store situated near the intersection of Maple Street and Ridge Road in Wichita, KS. Parcel 3 is 0.86 acres with 205 feet of frontage along Maple Street. Parcel 4 is 0.91 acres with 206 feet of frontage along Maple Street. These parcels can be purchased separately or together. This is an excellent location for restaurant/retail uses with the advantage of being in an established and proven trade area with such well-known neighbors as: Target Wal-Mart Kohl’s Department Store Sam’s Wholesale Club Golden Corral I-Hop Lowe’s Home Improvement The Home Depot Circuit City OfficeMax Best Buy TJ Maxx Outback Steakhouse Carlos O’Kelly’s Mexican Cafe Office Depot Sheplers Western Wear Michael’s McDonald’s Texas Roadhouse Petco Burlington Coat Factory McAlister’s Deli and many more ... Towne West Square Mall, the largest shopping mall in west Wichita, is located on Maple Street approximately 2.5 miles east of the site. Towne West Square is anchored by Dillard’s, JCPenney, and Sears. The site is ideally located near several restaurants and directly west from Lowe’s Home Improve- ment Center. The Maple and Ridge Road intersection (44,923 cars/day) provides the primary access to the pad sites with additional traffic also coming from Kellogg (US-54) and Ridge Road (76,573 cars/day). -

Robo-Expo Planning Guide

ROBO-EXPO PLANNING GUIDE PVC PIRATES TEAM 1058 FIRST ROBOTIC COMPETITION LONDONDERRY HIGH SCHOOL LONDONDERRY, NEW HAMPSHIRE ROBO-EXPO SEPTEMBER 6, 2014 PHEASANT LANE MALL, NASHUA, NH March 2015 Congratulations on your decision to host a Robo-Expo event in your area. This manual is a guideline of steps to assist you in hosting a successful event. It is not required that you follow these exact steps. During the planning process for your event, record notes in this manual to reference for next year. It will be easier to have all the information in one binder. You can even bring the information to the event for easy reference. If you need assistance or have questions, please contact us. PVC PIRATES FRC TEAM 1058 LONDONDERRY HIGH SCHOOL 295 MAMMOTH ROAD LONDONDERRY, NEW HAMPSHIRE 03053-3095 (603) 432-6941 ROBO-EXPO Robo-Expo is an all-encompassing public outreach effort designed to showcase FIRST and all the programs it has to offer. Utilizing the high-traffic nature of a shopping mall, teams from all disciplines of FIRST demonstrate their robots to gain the attention and excitement of shoppers, and then engage spectators in discussion about FIRST, and how it can play a role in inspiring students to pursue careers in science and technology. In short, Robo-Expo is… A HIGH-VISIBILITY, HIGH-VOLUME, LOW-COST OUTREACH EVENT TO INSPIRE OTHERS WITH OUR REAL-WORLD APPLICATION OF ROBOT BUILDING AND PROBLEM SOLVING SKILLS. IT’S AN OPPORTUNITY TO SHOW WHY WE LOVE FIRST, AND HOW IT FOSTERS A PASSION FOR SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY, ENGINEERING AND MATH, WHILE ALSO TEACHING REAL WORLD SKILLS THAT LAST A LIFETIME. -

Tihen Notes from 1979 Wichita Eagle, P

WICHITA STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES’ DEPARTMENT OF SPECIAL COLLECTIONS Tihen Notes from 1979 Wichita Eagle, p. 1 Dr. Edward N. Tihen (1924-1991) was an avid reader and researcher of Wichita newspapers. His notes from Wichita newspapers -- the “Tihen Notes,” as we call them -- provide an excellent starting point for further research. They present brief synopses of newspaper articles, identify the newspaper -- Eagle, Beacon or Eagle-Beacon -- in which the stories first appeared, and give exact references to the pages on which the articles are found. Microfilmed copies of these newspapers are available at the Wichita State University Libraries, the Wichita Public Library, or by interlibrary loan from the Kansas State Historical Society. TIHEN NOTES FROM 1979 WICHITA EAGLE Wichita Eagle Thursday, January 4, 1979 page 4B. Southern Pacific Company and its subsidiaries have filed an application to purchase a 965 mile segment of the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad Company between Santa Rosa, New Mexico and St. Louis via Kansas City, for $57 million. Details. Saturday, January 6, 1979 page 8C. Report of death yesterday of Leo J. Dondlinger, 72, of 220 Morningside, retired secretary- treasurer of Dondlinger and Sons Construction Company. The firm was founded in 1925 by Nick Dondlinger, a carpenter who moved here from Claflin, Kansas. With the help of his four sons the firm expanded and built major projects such as Cessna Stadium and Henry Levitt Arena at Wichita State University, Kapaun High School, and the Kansas Gas and Electric Building. Leo joined the firm in 1940 and retired in 1977. Survivors include his widow, Euna Mae, two sons, Patrick and John and a step-son, Jeff Craddock, Jr., of Wichita, a daughter, Mrs. -

In the United States Bankruptcy Court for the District of Delaware

Case 18-11780-BLS Doc 408 Filed 09/20/18 Page 1 of 3 IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE ) CHAPTER 11 In re: ) ) Case No. 18-11780 (BLS) Brookstone Holdings Corp, et al., ) (Jointly Administered) ) Debtors. ) Objection Deadline: September 24, 2018 at 4:00 p.m. (ET) ) Hearing Date: October 1, 2018 at 10:00 a.m. (ET) ) ) Related to Docket No. 345 LIMITED OBJECTION OF SIMON PROPERTY GROUP, L.P. TO DEBTORS’ NOTICE OF POSSIBLE ASSUMPTION AND ASSIGNMENT OF CERTAIN EXECUTORY CONTRACTS AND UNEXPIRED LEASES IN CONNECTION WITH SALE Simon Property Group, L.P. as Landlord and/or Managing Agent (“Simon”), by its undersigned attorney, hereby files its Limited Objection to the Debtors’ Notice of Possible Assumption and Assignment of Certain Executory Contracts and Unexpired Leases in Connection with Sale [Docket No. 345] (the “Notice”). In support of the same, Simon states as follows: BACKGROUND 1. Brookstone Holdings Corp., and its affiliated debtors and debtors-in-possession (collectively, the “Debtors”), filed voluntary petitions for relief under Chapter 11 of the United States Bankruptcy Code on August 2, 2018 (the “Petition Date”). 2. The Debtors continue to operate their business and manage their properties as debtors-in-possession pursuant to 11 U.S.C. §§ 1107(a) and 1108. 3. On September 10, 2018 Debtors filed their Notice of Possible Assumption and Assignment of Certain Executory Contracts and Unexpired Leases in Connection with Sale. This notice includes the proposed cure amounts believed to be due per the Debtors [Docket No. 345] (the “Cure Notice”). Case 18-11780-BLS Doc 408 Filed 09/20/18 Page 2 of 3 4. -

Wichita Travels

Wichita Travels Wichita Regional Transit Plan Easy-to-use routes Connections to other communities Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) on Douglas Ave May 2010 Prepared For Wichita Transit By The University of Kansas Urban Planning Department Graduate Transportation Planning Implementation Class (BRT, HNTB Corp.) ii iii Table of Contents Contents Chapter I: INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 1 A. Purpose and Need ............................................................................................................... 1 B. Goals and Objectives ........................................................................................................... 1 C. Study Area ........................................................................................................................... 2 D. Comparison to Peer Cities ................................................................................................... 4 E. Public Perception ................................................................................................................. 5 F. Study Team and Process ....................................................................................................... 8 Chapter II: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................. 11 Chapter III: EXISTING CONDITIONS ........................................................................................... 15 A. Introduction ................................................................................................................. -

Printed on 03/24/2015 State City Customer Location Name Location

printed on 03/24/2015 State City Customer Location Name Location Zip Phone AK Anchorage Nordstrom Anchorage 603 D Street 99501 907-279-7622 AL Hoover Von Maur Riverchase Galleria 2400 Riverchase Galleria 35244 205-982-4337 AZ Chandler Nordstrom Chandler Fashion Center 3199 West Chandler Boulevard 85226 480-855-2500 CA Cerritos Nordstrom Los Cerritos 300 Los Cerritos Center 90703 562-924-0940 CA Corte Madera Nordstrom Corte Madera 1870 Redwood Highway 94925 415-927-1690 CA Escondido Nordstrom Escondido 270 East Via Rancho Parkway 92025 760-740-0170 CA Glendale Nordstrom Nordstrom at the Americana at Brand 102 Caruso Avenue 91210 818-502-9922 CA Irvine Nordstrom Irvine Spectrum 101 Fortune Drive 92618 949-255-2800 CA Los Angeles Bloomingdales Century City Century City Shopping Center 90067 310-772-2100 CA Los Angeles Nordstrom Westside Pavilion 10830 West Pico Boulevard 90064 310-470-6155 CA Montclair Nordstrom Montclair Plaza 5015 Montclair Plaza Lane 91763 909-625-0821 CA Newport Beach Bloomingdales Newport Beach Fashion Island 92660 949-729-6600 CA Palo Alto Bloomingdales Stanford 1 Stanford Shopping Center 94304 650-463-2000 CA Riverside Nordstrom Tyler 3601 The Galleria at Tyler 92503 951-351-3170 CA Roseville Nordstrom Galleria at Roseville 1131 Galleria Boulevard 95678 916-780-7300 CA Sacramento Nordstrom Arden Fair 1651 Arden Way 95815 916-646-2400 CA San Francisco Bloomingdales Union Square 845 Market Street 94103 415-856-5300 CA San Francisco Nordstrom Stonestown 285 Winston Drive 94132 415-753-1344 CA San Francisco Nordstrom