Bannow Bay Special Protection Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

67Th. Annual Agricultural Show

Bannow & Rathangan Show Society (Affiliated to Irish Shows Association, Show Jumping Ireland and Irish Pony Society) Schedule of 67th. Annual Agricultural Show At Killag, Duncormick, Co. Wexford. on Thursday 14th. July, 2016. Judging of Ponies at 9.30 a.m. (Ring 6 at 10 a.m.) Judging of Horse Classes 10.00 a.m. Jumping Events start in Arena 1 at 10.00 a.m. Arenas 2 & 3 - 11.00 a.m. Arena 4 - 10.30 a.m. Dressage at 9. a.m. Dog Show at 2.00 p.m. Entries Close With Hon. Sec. on 1st. July. Secretary: Anne White, Killag, Duncormick, Co. Wexford. Mob: 087 6121008 Tel: 053 9148847 Asst. Secretary: Elizabeth Freeman, The Ballagh, Mob: 087 7560871 Tel: 053 9136588 Secretary, Home Industry Section: Tel: 085 1741236 Treasurers: Eileen Cullen, Pembrokestown, Duncormick. Ronald Scanlon, Balloughton, Wellingtonbridge. Safety Officers: Neil Murphy, Nick Sinnott, Peter Hayes, John Furlong, David Furlong, Fintan Ffrench, Donal Keane, Peadar Keane, George Whitehead, Martin Goff, Joe Scallan, Kevin Roche, Pat White, Nick White, Rory Hannigan, Matty Reville. www.bannowrathanganshow.com email: [email protected] Important Safety Notice Bannow & Rathangan Show Society will endeavor to assist and co-oper- ate with exhibitors regarding safety, however exhibitors shall accept absolute responsibility in respect of the control and behaviour of all their exhibits at the show. Exhibitors shall be solely responsible for all legal liability arising as a result of any injury or damage caused by an animal, their property or under their control at the show. Therefore, the exhibitor and trader must effect appropriate policies of insurance to indemnify the Bannow & Rathangan Show Society, its Officers and Members against any claim, action or proceedings brought against it as a result of the negligence or breach of duty of the Exhibitor or Trader. -

AP8 2018 Technical Advisors Report

Technical Advisors Report AP8 / 2018 Bannow Bay Oyster Aquaculture and Foreshore Licence Application Appeal Report prepared by MERC Consultants on behalf of Aquaculture Licences Appeals Board www.mercenvironmental.ie MERC Consultants Loughaunbeg Inverin. Co Galway [email protected] Tel: +353-91-442523 April 2019 ALAB AP8 Bannow Bay Appeal against Decision to Refuse Appeal Ref No. AP8/2018 Aquaculture Licences Appeals Board Technical Advisor’s Report Description: Assessment of the appeal against the Minister’s decision to refuse aquaculture and foreshore licences for the cultivation of pacific oysters at site reference T3/96 within Bannow Bay, Co. Wexford. Licence Application Department Ref No: AP8/2018 Applicant: AG Oysters Ltd Minister’s Decision: Licence Applications Refused to Grant Appeal Type of Appeal: Appeal against the decision of the Minister for Agriculture, Food and the Marine to refuse to grant an Aquaculture and Foreshore Licence to AG Oysters Ltd., for the cultivation of Pacific Oysters using bags and trestles at Bannow Bay, Co. Wexford on Site T03/96A Appellant(s): AG Oysters Ltd Observers: Fitzpatrick Oysters Ltd., Tomás Ffrench. Technical Advisor MERC Consultants Ltd. Date of site Inspection 03/04/2019 2 April 2019 ALAB AP8 Bannow Bay Appeal against Decision to Refuse Table of Contents 1.0 General Matters / Appeal Details ................................................................................. 4 1.1 Appeal Details & Observer Comments / Submissions ............................................. 4 1.2 Name -

County Wexford Biodiversity Action Plan 2013-2018

County Wexford Biodiversity Action Plan 2013-2018 Endorsed by the Elected Members of Wexford County Council on the 11 th November 2013 Protecting County Wexford’s Biodiversity Through Actions and Raising Awareness COUNTY WEXFORD BIODIVERSITY ACTION PLAN 2013-2018 Endorsed by the Elected Members of Wexford County Council on the 11 th November 2013 To Protect County Wexford’s Biodiversity Through Actions and Raising Awareness ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to gratefully acknowledge all those who made a submission to the plan and the members of the Wexford Biodiversity Working Group for their valuable contribution to the plan. Thanks are also extended to the Steering Committee members, which included Cliona O’Brien from the Heritage Council and Lorcan Scott, NPWS. Thanks are also extended to Dr.Amanda Browne & Padraic Fogarty who prepared the audit and review of the biological resource. Art and photography credits are paid to the entrants of the 2011 Biodiversity Art and Photography competitions. ACRONYMS BAP – Biodiversity Action Plan BoCCI - Birds of Conservation Concern in Ireland BWG – Biodiversity Working Group cSACs - Candidate Special Areas of Conservation Flora Protection Order - Flora (Protection) Order, S.I. No. 94 of 1999. Habitats Directive - 1992 EU Directive on the Conservation of Natural Habitats and of Wild Fauna and Flora IUCN - International Union for the Conservation of Nature NBAP – National Biodiversity Action Plan, (. National Biodiversity Action Plan, Dúchas. 2002, and ‘Actions for Biodiversity 2011-2016, Ireland’s National Biodiversity Plan’, Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht, 2011. NHA – Natural Heritage Area SAC – Special Area of Conservation SPA – Special Protection Area The Convention – UN Convention on Biological Diversity, signed at Rio Earth Summit 1992 The Guidelines – Guidelines for the Production of Local Biodiversity Action Plans, Heritage Council, 2003. -

1 1 Also...Dawn Chorus Walks in May Site Guide: The

Number 93 Summer 2019 • ISSN 1393-3434 Featuring.... Also.... BirdWatch Ireland history: Dawn chorus walks in May the landmark achievements Site Guide: The east midland lakes of theWINGS 1990s SUMMERSPRING and 2016 2019 2000s Barn Owl deaths on motorways1 Feeding Stations, Nestbox Everyday Feeding Station €20.00. (Feeders not included) Ideal for hanging Deluxe Bird Station €45.00. seed, peanut or Tom Chambers feeding station, other types of bird feed, including bird handcrafted from steel. The cakes. The pole is Build Your Own Nest components screw together to easy to place in the Box €10.00. For tits or make a sturdy stand. With three Classic Bird Station €30.00. ground or in a sparrows. With pre- separate feeders, water dish All-in-one feeding, watering container on your cut wood sections, and wire-mesh feeding tray. and bathing station. Suitable balcony or patio. screws, nails, washers A heavy-duty ground spike for use with patio base (sold Height 234 cm. and hanger. Adult ensures stability. Height 234 cm. separately). Height 220 cm. supervision required. Bird Feeders Kew Burton Square Cake Hanging Square Feeding Table Orangery Peanut Feeder London Squirrel-resistant London Squirrel-resistant Feeder €12.00. Slate-roofed €18.00. Ideal for gardens with €20.00. Slate-roofed wooden Peanut Feeder €22.00. Seed Feeder €22.00. wooden FSC feeder, specially limited space or to keep out of FSC feeder with attractive, Metal cage denies access Metal cage denies access to designed to hold one square reach of pets. Stainless steel mesh rustic design. With self- to squirrels, Jackdaws. -

County Council Meeting Minutes 8Th March 2021

County Council Meeting 08.03.21 WEXFORD COUNTY COUNCIL Minutes of Meeting of Wexford County Council Held Monday 8 March, 2021 (via MS TEAMS) Attendance: In the Chair: Cllr. Ger Carthy, Cathaoirleach. Councillors: BARDEN PAT FARRELL MARY MOORE JIM BARBARA- BELL MAURA FLEMING JOHN MURPHY ANNE BOLGER ANDREW FORDE TOM MURPHY BRIDIN BREEN PIP HEGARTY JOHN O’ROURKE JOHN BROWNE AIDAN HYNES DAVID O'SUILLEABHAIN FIONNTAIN BYRNE CATHAL KAVANAGH WILLIE OWENS JACKSER CODD JIM KELLY LEONARD SHEEHAN MICHAEL CODD-NOLAN KATHLEEN KENNY DONAL STAPLES FRANK CONNICK ANTHONY LAFFAN GARY SULLIVAN JOE DEVEREUX DIARMUID LAWLOR GEORGE WALSH OLIVER DONOHOE ANTHONY MCDONALD LISA WHELAN MICHAEL Officials: Mr. T. Larkin, Director of Services Mr. E. Hore, Director of Services Ms. A. O’Neill, Head of Finance Ms. A. Byrne, A/Director of Services Ms. C. Godkin, A/Director of Services Mr. D. Minogue, County Secretary Mr. Sean Dobbs, Project Manager, Roads Department Apologies: Mr. T. Enright, Chief Executive Page 1 of 10 County Council Meeting 08.03.21 Votes of Sympathy: The Council expressed sympathy to the families of the following recently deceased: o Ms. Leona Reville, Bannow o Mr. Patsy Bennett, Clonroche o Ms. Helen McGreevy, Clonroche o Mr. James Doran, Tintern o Ms. Brigid Murphy, Wellington Bridge o Mrs. Betty Donovan, Wexford Town o Mr. Ken O’Hara, Rosslare Harbour o Ms. Dympna Donohoe, Curracloe o Ms. Margaret Jackman, Killlurin o Ms. Stacia Ryan, New Ross o Mr. Martin O’Neill, New Ross o Mr. Patrick (Nicko) Hamilton, New Ross o Mr. John Doyle, New Ross o Mr. Denis North, New Ross o Mr. -

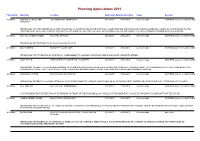

Planning Applications 2015

Planning Applications 2015 Planning No Applicant Location Application Date Decision Date Stage Decision 20150001 THOMAS & CAROL ANN CULLENSTOWN, HORETOWN 05/01/2015 25/02/2015 Decision made GRANTED subject to CONDITIONS DONOVAN PERMISSION FOR THE RETENTION OF THE FOLLOWING: (A) ALTERATIONS TO THE EXISTING FLOOR PLAN AND ELEVATIONS OF EXISTING DWELLING HOUSE, (B) ALTERATIONS TO THE EXISTING FOUL TREATMENT SYSTEM 90 MINOR ALTERATIONS TO THE EXISTING LOCATION OF DWELLING ALL PREVIOUSLY APPROVED UNDER PLANNING REGISTER 20063496 20150002 MICHAEL & TOMAS CODD KILLIANE, DRINAGH 05/01/2015 25/02/2015 Decision made GRANTED subject to CONDITIONS PERMISSION TO CONSTRUCT A MILKING PARLOUR FACILITY 20150003 OLIVIA BYRNE KILMURRY, COURTOWN 06/01/2015 25/02/2015 Decision made GRANTED subject to CONDITIONS PERMISSION FOR RETENTION OF EXISTING 84.4 SQ/M DOMESTIC GARAGE/ WORKSHOP AND ASSOCIATED CONCRETE APRON 20150004 TONY KELCH PARKANNESLEY LOWER, BALLYGARRETT 06/01/2015 25/02/2015 Decision made GRANTED subject to CONDITIONS PERMISSION TO ERECT A 65.09 SQ/M EXTENSION TO 63.4SQ/M SINGLE STOREY DWELLING HOUSE COMPRISING OF A DORMER ROOF TO ACCOMMODATE KITCHEN-LIVING ROOM AND PROVISION OF FRONT PORCH AND ALTERATIONS TO EXISTING GROUND FLOOR LAYOUT AND CONSTRUCTION OF NEW DOMESTIC GARAGE 20150005 DESMOND HATTON BALLINROAD, KILCORMICK 06/01/2015 27/02/2015 Decision made GRANTED subject to CONDITIONS PERMISSION TO ERECT A 41.4SQ/M EXTENSION TO EXISTING DOMESTIC GARAGE COMPRISING OF AN OPEN CAR PORT, GARDEN EQUIPMENT AND FUEL STORE AND UTILITY AREA 20150006 REV. JIM FINN BALLYREGAN, ROSSMINOGE 07/01/2015 27/02/2015 Decision made GRANTED subject to CONDITIONS 1) PERMISSION FOR THE ERECTION OF EXTENSION TO FRONT OF EXISTING DWELLING HOUSE 2) PERMISSION FOR CHANGE OF WINDOW TO DOOR ON FRONT ELEVATION. -

RTP Route Listing Per TCU Wexford TCU Route Name Route Number

RTP Route listing per TCU Wexford DRT ROUTES RRS ROUTES TCU Route Name Route Number TCU Route Name Route Number Wexford Askamore to Gorey 421 Wexford R 387 Wexford - Rosslare 387 Wexford Ballinaboola to Wexford 7415 Wexford R 389 Riverchapel to Gorey 389 Wexford Balliniry to New Ross 430 Wexford R388 Carrig on Bannow to Wexford 388 Wexford Ballycullane to Fethard on Sea 9492 Wexford R368 Tullow -Enniscorthy - New Ross 368 Wexford Ballyhogue to Enniscorthy 432 Wexford R369 Bunclody - Enniscorthy 369 Wexford Ballymitty to Wexford 409 Wexford Ballywilliam to Enniscorthy 433 Wexford Boolavogue to Enniscorthy 3180 Wexford Bridgetown to Wexford 414 Wexford Buffers Alley Rural Connect 4782 Wexford Campile to Wexford 429 Wexford Camross to Wexford 2207 Wexford Carne to Wexford 412 Wexford Carrig on Bannow Rural Connect 465 Wexford Carrig on Bannow to Waterford. 434 Wexford Carrowreagh School 447 Wexford Castlegardens to Enniscorthy Mon 3170 Wexford Castletown to Gorey 416 Wexford Clongeen to Carrig on Bannow 464 Wexford Clongeen to Waterford College Svc 426 Wexford Clongeen to Wexford 431 Wexford Collect & Connect to R387 2269 Wexford Courtown Rural Connect 4781 Wexford Crossabeg to Wexford 413 Wexford Duncormick Area DRT 9554 Wexford Enniscorthy to Ballon 4778 Wexford Enniscorthy to Wexford Tues 3172 Wexford Fethard on Sea to Waterford College Svc 425 Wexford Foulksmills to Wexford 2206 Wexford Friday Community Link 446 Wexford Gorey Rural Connect 4779 Wexford Grantstown to New Ross 427 Wexford Hook Area to Wexford 2205 Wexford Hook Rural Connect 466 Wexford Kilmore 420 Wexford Kilmuckridge to Gorey 419 Wexford Loreto Village to Enniscorthy 411 Wexford Monamolin to Gorey 418 Wexford New Ross Rural Service 4726 Wexford Oulart to Wexford 415 Wexford Piercestown AR 449 Wexford Rosslare to Wexford 407 Wexford Rural Commute to Wexford 4785 Wexford The Ballagh to Wexford 7137 Wexford The Ballagh/Glenbrien to Wexford 7653. -

Numbers I to XIV DECIES Is Published by the OLD WATERFORD

Number XV September 1980 INDEX -Numbers I to XIV DECIES is published by the OLD WATERFORD SOCIETY and is sent free to members in January, May and September. USE 0 F INDEX This index is in three sections,as follows: PRIMARY INDEX SECONDARY INDEX Persons and Pls.ces Relating to South-ERSt Ireland. 11 SUPPLEYEiiTRRY INDEX Contributors 38 An index of subjects has not been ~ttempted- it is nssumed that topics covered can be gleaned from scanning the Primary Index. The context in which persons and places listed in the Second2.ry Index occur may be gauged from referring issue and page number back to Primary Index. Throughout, Roman numerals nre used for issue number (even though letters or Arabic numbers had been Used in the actual issues) and Ar~bicnumbers indicate the pages. Thus, X 11 refers to issue number ten -(January 1979) page eleven. THANKS T 0 The tedious job of indexing Persons snd Places in each issue was undertaken by the following members of the OVS (with pfirts of issues done, in brackets) : Miss Y.A.Brennan-Smith,XIII ; Fx. J.S. Carroll, IX ( XIV); Mr. L. E~chthiqheirn,~JII;Mrs. L.Gallagher 111, IV (%XIV)gMr.F.Heylin, VI; Yz.J.Hodge, 1,II (kXIV); Nr.J.Yulholland VIII; Mr.T.Xolan,XI, (V1 ~~XIV);?Xss S.01Neil19XII (& XIV); Miss E.OtReilly ,X; Mrs. E. Webster , V. Together they accumulated s 264 inch pile of index cards and the formidable task of translating them into typescript fell largely on Mrs. Eileen Johnston. PRIMARY INDEX TABU 0 CQIJrniTs Omitted from this table are editorials, reports of 0.W.S , A.G.M.s, short questions, and progpmmes of O.W.S. -

“The Black /Fitzhenry's Castle” Clonmines Wexford 'Garderobe

“The Black /Fitzhenry’s Castle” Clonmines Wexford ‘Garderobe Chute’ Proposed structural repair/restoration of garderobe chute opening – East Elevation SMR No.: WX045 - 012001 Grid Ref: E. 684359; N. 613028 (ITM) On behalf of the Codd Family 10th October 2014 Arnaud De Volder BA MSc (Author) Paul Murphy BA MA H.Dip. “Black Castle”, Clonmines, Wexford – Garderobe Chute 1 Abstract This report provides an overview of the “Black” or “FitzHenry’s Castle” with a particular emphasis on the question of if the fracture visible on the east face of the tower-house is the location of the discharge for the garderobe/waste chute. It also makes a number of recommendations based on the conclusion that this is not the discharge point, a conclusion which is reached on the basis of the available evidence outlined in the report, as-well-as similar tower houses in the region. Figure 1. East Elevation "Black Castle", Clonmines, Wexford. Scale bar is in 20cm segments. (Photo: Author & Paul Murphy) 10 October 2014 “Black Castle”, Clonmines, Wexford – Garderobe Chute 2 Contents Abstract 1 Table of Figures 3 1. Summary 4 2. Introduction 5 3. The Tower-house “Black” or “FitzHernry’s Castle” 6 4. Description of “Black” or “FitzHernry’s Castle” - garderobe and chute 7 5. Discussion 8 6. Conclusions & Recommendations 11 Appendix 1 – General Site Topography 13 Appendix 2 – Floor Plans 14 Appendix 3 – East Elevation 16 Appendix 4 – North Elevation 17 Appendix 5 – Site Photographs (First and Second Floor over Vault) 18 Appendix 6 – Site Photographs (Loft under Vault & Ground Floor) 19 Appendix 7 – Site Photographs (East elevation) 21 Appendix 9 – Comparative Material 23 Bibliography 25 10 October 2014 “Black Castle”, Clonmines, Wexford – Garderobe Chute 3 Table of Figures FIGURE 1. -

St Vincent De Paul Wexford Calling on All Businesses and Householders to Donate Their Old Newspapers

St Vincent de Paul Wexford Calling on all Businesses and Householders to Donate their Old Newspapers St Vincent de Paul has announced a new project; the charity is appealing to the households and businesses of County Wexford to donate old newspapers by bringing them to a local St Vincent de Paul Newspaper Recycling Bin. St Vincent de Paul has partnered with Wexford community enterprise project, Recycling 2000, for this initiative. Recycling 2000 will recycle the newspapers making a donation to St Vincent de Paul for all newspapers collected at the nominated recycling points. All funds generated from this initiative will go directly to helping the people in need within our communities. “We are very excited about this initiative and are confident that the people of Wexford will again get behind us. Our goal is that Recycling 2000 will collect 50% more newspapers than they did last year which will translate into a sizable donation to the St Vincent de Paul.” commented Mary Dempsey, Wexford Area President, Society of St Vincent de Paul. The good work does not end there. Recycling 2000, a community based recycling project has an environmentally friendly ethos. All old newspapers collected will be used to produce environmentally based products. In addition, by sourcing a larger proportion of newspapers locally the level of handling and unnecessary transportation of old newspapers will be significantly reduced, thus reducing the carbon footprint of all involved. “The majority of households and businesses throughout the country are now segregating their waste and have adopted excellent recycling habits. We are now looking for these same people to make one more change and to bring their newspapers to a SVP Newspaper Recycle Bin. -

Bibliomara: an Annotated Indexed Bibliography of Cultural and Maritime Heritage Studies of the Coastal Zone in Ireland

BiblioMara: An annotated indexed bibliography of cultural and maritime heritage studies of the coastal zone in Ireland BiblioMara: Leabharliosta d’ábhar scríofa a bhaineann le cúltúr agus oidhreacht mara na hÉireann (Stage I & II, January 2004) Max Kozachenko1, Helen Rea1, Valerie Cummins1, Clíona O’Carroll2, Pádraig Ó Duinnín3, Jo Good2, David Butler1, Darina Tully3, Éamonn Ó Tuama1, Marie-Annick Desplanques2 & Gearóid Ó Crualaoich 2 1 Coastal and Marine Resources Centre, ERI, UCC 2 Department of Béaloideas, UCC 3 Meitheal Mara, Cork University College Cork Department of Béaloideas Abstract BiblioMara: What is it? BiblioMara is an indexed, annotated bibliography of written material relating to Ireland’s coastal and maritime heritage; that is a list of books, articles, theses and reports with a short account of their content. The index provided at the end of the bibliography allows users to search the bibliography using keywords and authors’ names. The majority of the documents referenced were published after the year 1900. What are ‘written materials relating to Ireland’s coastal heritage’? The BiblioMara bibliography contains material that has been written down which relates to the lives of the people on the coast; today and in the past; their history and language; and the way that the sea has affected their way of life and their imagination. The bibliography attempts to list as many materials as possible that deal with the myriad interactions between people and their maritime surroundings. The island of Ireland and aspects of coastal life are covered, from lobster pot making to the uses of seaweed, from the fate of the Spanish Armada to the future of wave energy, from the sailing schooner fleets of Arklow to the County Down herring girls, from Galway hookers to the songs of Tory Islanders. -

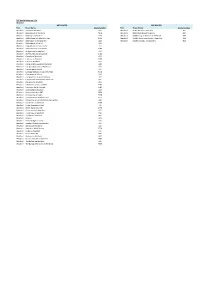

2021 Community Enhancement Programme Return Wexford.Xlsx

Name of AMOUNT GROUP / ORGANISATION TOWN/VILLAGE AWARDED AREA by LCDC Kilmore Scope Group Kilmore € 2,000 Oulart Community Centre Oulart € 1,000 The Boolavogue Bi Centennial development Co Operative society limited T/A Fr Murphy Centre Boolavogue € 1,000 South West Wexford Family Resource Centre Ramsgrange € 2,377 Ramsgrange Men's Group Ramsgrange € 275 Enniscorthy Swim Club Enniscorthy € 728 Tomhaggard Womens Shed Tomhaggard € 500 Ramsgrange Mens Shed Ramsgrange € 1,000 Coolgreany/Ballyfad woods walking trails Coolgreany/Ballyfad € 500 Ballyhogue Camogie Club Ballyhogue € 1,500 High Meadows Community Hub CLG Wexford Town € 3,000 Clongeen Community Development Group Clongeen € 2,000 Kilmuckridge Community & Family Resource Centre Kilmuckridge € 3,000 Cois Mara Community House Rosslare Strand € 2,000 Ballycullane Tidy Towns Ballycullane € 500 Ballymitty Community Development CLG Ballymitty € 2,000 Kilmuckridge Men's Shed Kilmuckridge € 1,000 St. Kevins Community Centre Tombrack Tombrack € 1,200 Southend Family Resource Centre / Southend Community Development Group Maudlintown € 1,000 Bridgetown Steering Group Bridgetown € 2,000 Tomhaggard Social Centre AKA Tomhaggard Community Development Group Tomhaggard € 2,000 Monageer Parish Grotto Group Monageer € 3,000 The May Byrne Community House Coolgreany € 1,600 Wexford Volunteer Centre Wexford Town € 2,000 Adamstown Tidy Towns Adamstown € 1,000 Camross Hall Ltd Camross € 2,500 Shamrocks GAA Club Enniscorthy € 2,000 Seashell Girl Guides Ballygarrett € 933 Ballygarrett Realt Na Mara GAA Club