The Trials of Creativity: a Rhetorical Analysis of a View from the Bridge and the Crucible by Arthur Miller

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 2019

Vol. 11 december 2019 — issue 12 issue iNSIDE: ‘10s roundup - OK BOOMER - HOW TO LEAVE A CONCERT - SALACIOUS VEGAN CRUMbS - DRUNK DETECTIVE STARKNESS - ANARCHY FROM THE GROUND UP - places to poo - STILL NERDY - small bizness Saturday - ASK CREEPY HORSE - record reviewS - concert calendar Ok boomer It is amazing to me how quick the Inter- net is to shoot down some ageist, gener- ational bullshit in a way that completely 979Represent is a local magazine crawls under the skin of old people. I am referring to the “OK Boomer” memes flying around these days. The for the discerning dirtbag. comment refers to Baby Boomers, the septuagenarian generation whose cultural and economic thumb we have Editorial bored lived under my entire life. As a solid Gen X’er I have been told that I was really born too late, that everything cool Kelly Menace - Kevin Still that could possibly happen already happened in the ‘60s Art Splendidness and too bad for me because I wasn’t there. Boomers Katie Killer - Wonko Zuckerberg single handedly made casual sex cool, had the rad drugs, had the best rock & roll, and their peace and love Print jockey changed the world. Too bad for you, ’70s kid. You get to Craig WHEEL WERKER grow up under Reagan, high interest rates, single parent latchkey homes, the destruction of pensions, the threat of nuclear annihilation, “Just Say No”, doing a drug once Folks That Did the Other Shit For Us could get you hooked for life, and having sex once could CREEPY HORSE - MIKE L. DOWNEY - JORGE goyco - TODD doom you to death. -

October 18 - November 28, 2019 Your Movie! Now Serving!

Grab a Brew with October 18 - November 28, 2019 your Movie! Now Serving! 905-545-8888 • 177 SHERMAN AVE. N., HAMILTON ,ON • WWW.PLAYHOUSECINEMA.CA WINNER Highest Award! Atwood is Back at the Playhouse! Cannes Film Festival 2019! - Palme D’or New documentary gets up close & personal Tiff -3rd Runner - Up Audience Award! with Canada’ international literary star! This black comedy thriller is rated 100% on Rotten Tomatoes. Greed and class discrimination threaten the newly formed symbiotic re- MARGARET lationship between the wealthy Park family and the destitute Kim clan. ATWOOD: A Word After a Word “HHHH, “Parasite” is unquestionably one of the best films of the year.” After a Word is Power. - Brian Tellerico Rogerebert.com ONE WEEK! Nov 8-14 Playhouse hosting AGH Screenings! ‘Scorcese’s EPIC MOB PICTURE is HEADED to a Best Picture Win at Oscars!” - Peter Travers , Rolling Stone SE LAYHOU 2! AGH at P 27! Starts Nov 2 Oct 23- OPENS Nov 29th Scarlett Johansson Laura Dern Adam Driver Descriptions below are for films playing at BEETLEJUICE THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI Dir.Tim Burton • USA • 1988 • 91min • Rated PG. FEAT. THE VOC HARMONIC ORCHESTRA the Playhouse Cinema from October 18 2019, Dir. Paul Downs Colaizzo • USA • 2019 • 103min • Rated STC. through to and including November 28, 2019. TIM BURTON’S HAUNTED CLASSIC “Beetlejuice, directed by Tim Burton, is a ghost story from the LIVE MUSICAL ACCOMPANIMENT • CO-PRESENTED BY AGH haunters' perspective.The drearily happy Maitlands (Alec Baldwin and Iconic German Expressionist silent horror - routinely cited as one of Geena Davis) drive into the river, come up dead, and return to their the greatest films ever made - presented with live music accompani- Admission Prices beloved, quaint house as spooks intent on despatching the hideous ment by the VOC Silent Film Harmonic, from Kitchener-Waterloo. -

A View from the Bridge Arthur Miller

A View from the Bridge Arthur Miller Tuesday 19 January 2021 Module Introduction: • To develop analysis of contemporary drama texts • To analyse dramatic devices, language and structure and how they contribute to character and theme. • To explore characters, context and themes Learning Purposes this lesson ➢Consider contextual factors to help understand influences on the writer/text ➢Consider how dramatists use dramatic devices for particular effects ➢Consider how the use of setting and stage directions contribute to characterisation. Recap from previous learning Future Learning 1. What play did you recently study? ➢To study Arthur Miller’s A View ➢2. What helps define a tragedy? from the Bridge. ➢3. What are the conventions you ➢To analyse elements of the play associate with a play? such as characterisation, themes and stagecraft. Reading task • Read the worksheet about the writer and the play and then answer the questions on the task sheet. • You have up to 30 minutes for this task • Work in silence (make sure your microphone is muted) • If you have any questions type them into the chat Context and setting Section 1: Arthur Miller 1. Which event affected Arthur Miller’s parents’ business? 2. What did Miller study at university that influenced his life? 3. After his graduation, what work did Miller do apart from writing? 4. What was Miller’s first successful play? 5. For which play did Miller win the Pulitzer Prize? 6. Do you think Miller was considered a political writer? Provide a quotation to support your answer. 7. Which famous actress did Arthur Miller marry? 8. There are a number of references to Timebends. -

Presseinformation Cinedom Zeigt Depeche Mode Konzertfilm „Spirits in the Forest“ Mit Kinoexklusivem Bonusmaterial

Presseinformation Cinedom zeigt Depeche Mode Konzertfilm „Spirits in the forest“ mit kinoexklusivem Bonusmaterial • Wegen starker Nachfrage: Konzertfilm wird in drei Vorstellungen gezeigt • Preisgekrönter Regisseur Anton Corbijn dokumentiert besondere Augenblicke der Global Spirit Tour • Dokumentation mit Live-Impressionen und emotionalen Fan-Geschichten Köln, 18. November 2019 – Der Kölner Cinedom präsentiert in drei Vorstellungen den Konzert- und Dokumentarfilm „Spirits in the forest“ der britischen Synthie-Pop-Band Depeche Mode. Diese finden am 21.11. (20 Uhr), 24.11. (17 Uhr) und als Zusatztermin am 26.11. (20 Uhr) statt. Depeche Mode haben 2017 und 2018 im Rahmen ihrer „Global Spirit Tour“ insgesamt 115 Shows gespielt und sind vor über drei Millionen Fans weltweit aufgetreten. Den Abschluss der Tournee bildeten die Konzerte in der Berliner Waldbühne. „Spirit in the Forest“ ist damit eine Anspielung auf den englischen Namen der Berliner Waldbühne – Forest Stage. Die einzigartigen Auftritte der Band in der deutschen Hauptstadt wurden dabei filmisch von dem preisgekrönten Regisseur Anton Corbijn, der die Band langjährig begleitete, festgehalten. In seinem Film zeigt der Niederländer zudem sechs Fans und ihre emotionalen Geschichten zu Depeche Mode. „Depeche Mode gehören seit Jahrzehnten zu den erfolgreichsten Bands der Welt. Deshalb wollten wir den Konzertfilm unbedingt im Cinedom zeigen. Aufgrund der hohen Nachfrage, bieten wir eine weitere Vorstellung an, damit auch jeder Fan die Chance erhält, die wunderbare Musik und die außergewöhnlichen Live-Shows dieser Band zu feiern“ sagt Cinedom-Geschäftsführer Ralf Schilling. Tickets sind wie gewohnt an der Kinokasse oder online erhältlich. ___________________________________________________________________________________ Kontakt: Cinedom Kinobetriebe GmbH, Im MediaPark 1, 50670 Köln Über den Cinedom Der Cinedom ist ein Multiplex-Kino in der Kölner Innenstadt und wurde 1991 eröffnet. -

Recognising Talent in Fiction, Film and Art

EMERGING VOICES RECOGNISING TALENT IN FICTION, FILM AND ART SUPPORTED BY: Emerging Voices 2015 Today we celebrate the voices of tomorrow. OppenheimerFunds and the Financial Times would like to congratulate the 2015 Emerging Voices Awards winners and say thank you to all the writers, filmmakers and artists in emerging markets who continue to inspire us every day. Art, Cristina Planas Fiction, Chigozie Obioma Film, Yuhang Ho For more information about the Emerging Voices Awards, visit emergingvoicesawards.com and join the conversation with #EmergingVoices. ©2015 OppenheimerFunds Distributor, Inc. FOREWORD ‘THESE AWARDSFULFILLED ALL THE ORD HOPESWEHAD WHENWESTARTED’ REW FO hy aset of awards for artists, Elif Shafak and Alaa Al Aswany, celebrated film-makers and writers from novelists from Turkey and Egypt respectively, emerging market countries? debating the nature of literature, we knew we When Justin Leverenz, director were privileged to be present. Wof emerging market equities at In the art category, the judges were most OppenheimerFunds, approached the Financial impressed by Lima-based Cristina Planas, Times with the idea, we were intrigued. whose work took in environmental, politicaland The FT has long been following the rise to religious themes. The tworunners-up, Fabiola prominence of those countries challenging the MenchelliTejeda, wholives in Mexico City, and financial, strategic and political dominance Pablo Mora Ortega, born in Medellín, Colombia, of the hitherto wealthyworld. What did their submitted strikingly different works. Menchelli artists have to teach us? This would be a Tejeda’s photographs showedthe interaction chance to find out. of light and shadow. Ortega’s installation, It would be disingenuous not to pointout sculptures and video showedwhat he called “the that there were financial motivations too. -

Announcing a VIEW from the BRIDGE

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, PLEASE “One of the most powerful productions of a Miller play I have ever seen. By the end you feel both emotionally drained and unexpectedly elated — the classic hallmark of a great production.” - The Daily Telegraph “To say visionary director Ivo van Hove’s production is the best show in the West End is like saying Stonehenge is the current best rock arrangement in Wiltshire; it almost feels silly to compare this pure, primal, colossal thing with anything else on the West End. A guileless granite pillar of muscle and instinct, Mark Strong’s stupendous Eddie is a force of nature.” - Time Out “Intense and adventurous. One of the great theatrical productions of the decade.” -The London Times DIRECT FROM TWO SOLD-OUT ENGAGEMENTS IN LONDON YOUNG VIC’S OLIVIER AWARD-WINNING PRODUCTION OF ARTHUR MILLER’S “A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE” Directed by IVO VAN HOVE STARRING MARK STRONG, NICOLA WALKER, PHOEBE FOX, EMUN ELLIOTT, MICHAEL GOULD IS COMING TO BROADWAY THIS FALL PREVIEWS BEGIN WEDNESDAY EVENING, OCTOBER 21 OPENING NIGHT IS THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 12 AT THE LYCEUM THEATRE Direct from two completely sold-out engagements in London, producers Scott Rudin and Lincoln Center Theater will bring the Young Vic’s critically-acclaimed production of Arthur Miller’s A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE to Broadway this fall. The production, which swept the 2015 Olivier Awards — winning for Best Revival, Best Director, and Best Actor (Mark Strong) —will begin previews Wednesday evening, October 21 and open on Thursday, November 12 at the Lyceum Theatre, 149 West 45 Street. -

Two Tendencies Beyond Realism in Arthur Miller's Dramatic Works

Inês Evangelista Marques 2º Ciclo de Estudos em Estudos Anglo-Americanos, variante de Literaturas e Culturas The Intimate and the Epic: Two Tendencies beyond Realism in Arthur Miller’s Dramatic Works A critical study of Death of a Salesman, A View from the Bridge, After the Fall and The American Clock 2013 Orientador: Professor Doutor Rui Carvalho Homem Coorientador: Professor Doutor Carlos Azevedo Classificação: Ciclo de estudos: Dissertação/relatório/Projeto/IPP: Versão definitiva 2 Abstract Almost 65 years after the successful Broadway run of Death of a Salesman, Arthur Miller is still deemed one of the most consistent and influential playwrights of the American dramatic canon. Even if his later plays proved less popular than the early classics, Miller’s dramatic output has received regular critical attention, while his long and eventful life keeps arousing the biographers’ curiosity. However, most of the academic works on Miller’s dramatic texts are much too anchored on a thematic perspective: they study the plays as deconstructions of the American Dream, as a rebuke of McCarthyism or any kind of political persecution, as reflections on the concepts of collective guilt and denial in relation to traumatizing events, such as the Great Depression or the Holocaust. Especially within the Anglo-American critical tradition, Miller’s plays are rarely studied as dramatic objects whose performative nature implies a certain range of formal specificities. Neither are they seen as part of the 20th century dramatic and theatrical attempts to overcome the canons of Realism. In this dissertation, I intend, first of all, to frame Miller’s dramatic output within the American dramatic tradition. -

Title Diversity of Ritual Spirit Performances Among the Baka

Diversity of Ritual Spirit Performances among the Baka Title Pygmies in Southeastern Cameroon Author(s) TSURU, Daisaku African study monographs. Supplementary issue (1998), 25: Citation 47-84 Issue Date 1998-03 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/68392 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, Suppl. 25: 47 - 84, March 1998 47 DIVERSITY OF RITUAL SPIRIT PERFORMANCES AMONG THE BAKA PYGMIES IN SOUTHEASTERN CAMEROON Daisaku TSURU Graduate School ofScience, Kyoto University ABSTRACT Ritual spirit performances among the Baka of Southeast Cameroon were studied. Through an extensive survey, characteristics and distribution pattern of the performances were described and classified. The social background of the diversification was also analyzed. The kinds and combinations of spirit performances practiced in bands are different among the bands. Such diversity is derived through two processes. (1) Guardianship for organizing spirit rituals is transmitted individually, which generates different combinations of spirit performances practiced in each band. (2) New spirit performances are created by indi viduals and practiced in the limited number of bands. As well as diversification in ritual practices, tendency toward standardization also takes place. Limited versions of new spirit performance are adopted by the Baka. Furthermore, creators of spirit perfonnances often incorporate the elements of existing spirit performance. Through these processes, the performances are eventually standardized. The variety of Baka spirit performance is maintained by a balance between diversification and standardization, which may reflect the present-day Baka need to establish social identity in a transition from the flexible and loosely organized nomadic society to a more sedentarized life in recent years. -

Skupina Depeche Mode Predvedie V Cykle Music & Film V Kine Lumičre

TLAČOVÁ SPRÁVA 22. november 2019 Skupina Depeche Mode predvedie v cykle Music & Film v Kine Lumière unikátnu koncertnú šou Kino Lumière v cykle Music & Film uvedie originálny a vizuálne pôsobivý koncertný film kultovej britskej kapely Depeche Mode: SPIRITS in the Forest (2019). Zachytáva minuloročnú vzrušujúcu šou kapely v amfiteátri Waldbühne v Berlíne a zároveň ponúka pohľad do života šiestich jej fanúšikov. Kino Lumière uvedie film na dvoch projekciách, prvá, naplánovaná na 26. novembra 2019, sa hneď po zverejnení vypredala, druhá sa uskutoční v piatok 29. novembra 2019 o 20.30 hod. Depeche Mode počas rokov 2017 – 2018 odohrali na svojom Global Spirit Tour k svojmu 14. štúdiovému albumu 115 koncertov pre viac než 3 milióny fanúšikov po celom svete. Na koncert v amfiteátri Waldbühne v Berlíne zavolali svojho dlhoročného spolupracovníka, režiséra Antona Corbijna, autora klipov ich svetoznámych hitov ako Personal Jesus alebo Enjoy the Silence, aby zachytil neskrotnú energiu ich vystúpení a spolu s ňou aj príbehy šiestich najvernejších fanúšikov. Okrem jedinečnej koncertnej šou tak film ponúka aj veľmi intímny pohľad na to, ako sa tvorba Depeche Mode premieta do osobných životov ich priaznivcov. "Je až neuveriteľné, ako dokážu Depeche Mode ovplyvňovať životy ľudí,“ povedal o filme režisér Anton Corbijn. „Títo fanúšikovia majú rozmanité príbehy a pochádzajú z odlišných kultúrnych prostredí, takže sme si stanovili plán, že ich budeme Filmovať v ich domácom prostredí a následne ich všetkých dostaneme na miesto koncertu." Corbijn sa domnieva, že tak rôznorodú skupinu ľudí spájajú práve texty skladieb Martina Gora. "Témy Martinových piesní oslovujú množstvo ľudí, ktorí majú pocit, že potrebujú sprievodcu alebo pomocnú ruku.“ „Na rozdiel od filmu Depeche Mode: 101 z roku 1989, ktorý sleduje amerických Fanúšikov kapely, tento dokument prezentuje dojímavé príbehy šiestich Fanúšikov Depeche Mode z rôznych krajín a kontinentov,“ približuje snímku Miro Ulman, dramaturg cyklu Music & Film. -

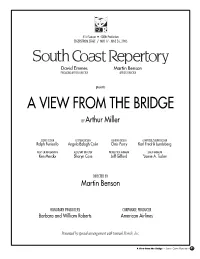

A View from the Bridge

41st Season • 400th Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / MAY 17 - JUNE 26, 2005 David Emmes Martin Benson PRODUCING ARTISTIC DIRECTOR ARTISTIC DIRECTOR presents A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE BY Arthur Miller SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN COMPOSER/SOUND DESIGN Ralph Funicello Angela Balogh Calin Chris Parry Karl Fredrik Lundeberg FIGHT CHOREOGRAPHER ASSISTANT DIRECTOR PRODUCTION MANAGER STAGE MANAGER Ken Merckx Sharyn Case Jeff Gifford *Jamie A. Tucker DIRECTED BY Martin Benson HONORARY PRODUCERS CORPORATE PRODUCER Barbara and William Roberts American Airlines Presented by special arrangement with Samuel French, Inc. A View from the Bridge • SOUTH COAST REPERTORY P1 CAST OF CHARACTERS (In order of appearance) Alfieri ....................................................................................... Hal Landon Jr.* Eddie ........................................................................................ Richard Doyle* Louis .............................................................................................. Sal Viscuso* Mike ............................................................................................ Mark Brown* Catherine .................................................................................... Daisy Eagan* Beatrice ................................................................................ Elizabeth Ruscio* Marco .................................................................................... Anthony Cistaro* Rodolpho .......................................................................... -

William & Mary Theatre Main Stage Productions

WILLIAM & MARY THEATRE MAIN STAGE PRODUCTIONS 1926-1927 1934-1935 1941-1942 The Goose Hangs High The Ghosts of Windsor Park Gas Light Arms and the Man Family Portrait 1927-1928 The Romantic Age The School for Husbands You and I The Jealous Wife Hedda Gabler Outward Bound 1935-1936 1942-1943 1928-1929 The Unattainable Thunder Rock The Enemy The Lying Valet The Male Animal The Taming of the Shrew The Cradle Song *Bach to Methuselah, Part I Candida Twelfth Night *Man of Destiny Squaring the Circle 1929-1930 1936-1937 The Mollusc Squaring the Circle 1943-1944 Anna Christie Death Takes a Holiday Papa is All Twelfth Night The Gondoliers The Patriots The Royal Family A Trip to Scarborough Tartuffe Noah Candida 1930-1931 Vergilian Pageant 1937-1938 1944-1945 The Importance of Being Earnest The Night of January Sixteenth Quality Street Just Suppose First Lady Juno and the Paycock The Merchant of Venice The Mikado Volpone Enter Madame Liliom Private Lives 1931-1932 1938-1939 1945-1946 Sun-Up Post Road Pygmalion Berkeley Square RUR Murder in the Cathedral John Ferguson The Pirates of Penzance Ladies in Retirement As You Like It Dear Brutus Too Many Husbands 1932-1933 1939-1940 1946-1947 Outward Bound The Inspector General Arsenic and Old Lace Holiday Kind Lady Arms and the Man The Recruiting Officer Our Town The Comedy of Errors Much Ado About Nothing Hay Fever Joan of Lorraine 1933-1934 1940-1941 1947-1948 Quality Street You Can’t Take It with You The Skin of Our Teeth Hotel Universe Night Must Fall Blithe Spirit The Swan Mary of Scotland MacBeth -

A View from the Bridge Study Guide

STATE THEATRE COMPANY SOUTH AUSTRALIA AND AUSTRALIAN GAS NETWORKS PRESENT A View from the Bridge BY ARTHUR MILLER Study with State SYNOPSIS A View from the Bridge is a two-act play set in Red Hook, a working class shipping port in Brooklyn, New York. Narrated by a lawyer, Alfieri, the story centres on the Carbone family – dock worker Eddie, his wife Beatrice and their niece Catherine. The arrival of Beatrice’s cousins, Rodolpho and Marco, propels the action of the play. As the cousins illegally seek work and a better life in the United States, their presence brings to light the hidden desires of each member of the Carbone family. For more, watch the trailer for the show online: statetheatrecompany.com.au/shows/a-view-from-the-bridge RUNNING TIME Approximately 140 minutes (including 20 minute interval). SHOW WARNINGS Contains adult themes, sexual references, mild coarse language, strong violence and the use of herbal cigarettes. Contents INTRODUCING THE PLAY Creative team ............................... 4-5 An interview with the director ............................... 6-7 An introduction to the life of Arthur Miller ............................... 8-9 Director’s note from Kate Champion ................................ 10 What next? ................................. 11 CHARACTERS & CHARACTERISATION Who is Eddie Carbone?: interview ........................... 12-13 Speaking up: interview ........................... 14-15 Cast Q&A: interviews ........................... 16-17 Exploring the characters ........................... 18-21 What