Tripping with Synthetic Cannabinoids (“Spice”): Anecdotal and Experimental Observations in Animals and Man

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DEPARTMENT of JUSTICE Drug Enforcement

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 08/03/2021 and available online at DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICEfederalregister.gov/d/2021-16499, and on govinfo.gov Drug Enforcement Administration Bulk Manufacturer of Controlled Substances Application: Cerilliant Corporation [Docket No. DEA-873] AGENCY: Drug Enforcement Administration, Justice. ACTION: Notice of application. SUMMARY: Cerilliant Corporation has applied to be registered as a bulk manufacturer of basic class(es) of controlled substance(s). Refer to Supplemental Information listed below for further drug information. DATES: Registered bulk manufacturers of the affected basic class(es), and applicants therefore, may file written comments on or objections to the issuance of the proposed registration on or before [INSERT DATE 60 DAYS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER]. Such persons may also file a written request for a hearing on the application on or before [INSERT DATE 60 DAYS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER]. ADDRESS: Written comments should be sent to: Drug Enforcement Administration, Attention: DEA Federal Register Representative/DPW, 8701 Morrissette Drive, Springfield, Virginia 22152. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: In accordance with 21 CFR 1301.33(a), this is notice that on June, 24, 2021, Cerilliant Corporation, 811 Paloma Drive, Suite A, Round Rock, Texas 78665-2402, applied to be registered as a bulk manufacturer of the following basic class(es) of controlled substance(s): Controlled Substance Drug Code Schedule 3-Fluoro-N-methylcathinone -

Analysis of Synthetic Cannabinoids and Drugs of Abuse Amongst HIV-Infected Individuals

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Student Theses John Jay College of Criminal Justice Fall 12-2016 Analysis of synthetic cannabinoids and drugs of abuse amongst HIV-infected individuals Jillian M. Wetzel CUNY John Jay College, [email protected] How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_etds/2 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] i Analysis of synthetic cannabinoids and drugs of abuse amongst HIV-infected individuals A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Forensic Science John Jay College of Criminal Justice City University of New York Jillian Wetzel December 2016 ii Analysis of synthetic cannabinoids and drugs of abuse amongst HIV-infected individuals Jillian Michele Wetzel This thesis has been presented to and accepted by the Office of Graduate Studies, John Jay College of Criminal Justice in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Forensic Science Thesis Committee: Thesis Advisor: Marta Concheiro-Guisan, Ph.D. Second Reader: Shu-Yuan Cheng, Ph.D. External Reader: Richard Curtis, Ph.D. iii Acknowledgements My greatest and sincerest gratitude goes towards my thesis advisor, professor, and mentor, Dr. Marta Concheiro-Guisan. You have educated me in more ways I thought possible and I am so thankful for all the experiences you have provided me with. As an educator you not only have taught me, but also have inspired me inside and outside the classroom. -

Recommended Methods for the Identification and Analysis of Synthetic Cannabinoid Receptor Agonists in Seized Materials (Revised and Updated)

Recommended methods for the Identification and Analysis of Synthetic Cannabinoid Receptor Agonists in Seized Materials (Revised and updated) MANUAL FOR USE BY NATIONAL DRUG ANALYSIS LABORATORIES Photo credits: UNODC Photo Library; UNODC/Ioulia Kondratovitch; Alessandro Scotti. Laboratory and Scientific Section UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Recommended Methods for the Identification and Analysis of Synthetic Cannabinoid Receptor Agonists in Seized Materials (Revised and updated) MANUAL FOR USE BY NATIONAL DRUG ANALYSIS LABORATORIES UNITED NATIONS Vienna, 2020 Note Operating and experimental conditions are reproduced from the original reference materials, including unpublished methods, validated and used in selected national laboratories as per the list of references. A number of alternative conditions and substitution of named commercial products may provide comparable results in many cases, but any modification has to be validated before it is integrated into laboratory routines. Mention of names of firms and commercial products does not imply theendorsement of the United Nations. ST/NAR/48/REV.1 © United Nations, July 2020. All rights reserved, worldwide The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This publication has not been formally edited. Publishing production: English, Publishing and Library Section, United Nations Office at Vienna. Acknowledgements The Laboratory and Scientific Services of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) (LSS, headed by Dr. -

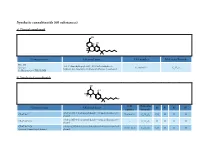

Synthetic Cannabinoids (60 Substances) A) Classical Cannabinoid

Synthetic cannabinoids (60 substances) a) Classical cannabinoid OH H OH H O Common name Chemical name CAS number Molecular Formula HU-210 3-(1,1’-dimethylheptyl)-6aR,7,10,10aR-tetrahydro-1- Synonym: 112830-95-2 C H O hydroxy-6,6-dimethyl-6H-dibenzo[b,d]pyran-9-methanol 25 38 3 11-Hydroxy-Δ-8-THC-DMH b) Nonclassical cannabinoids OH OH R2 R3 R4 R1 CAS Molecular Common name Chemical name R1 R2 R3 R4 number Formula rel-2[(1 S,3 R)-3- hydroxycyclohexyl]- 5- (2- methyloctan- 2- yl) CP-47,497 70434-82-1 C H O CH H H H phenol 21 34 2 3 rel-2[(1 S,3 R)-3- hydroxycyclohexyl]- 5- (2- methylheptan- 2- yl) CP-47,497-C6 - C H O H H H H phenol 20 32 2 CP-47,497-C8 rel-2- [(1 S,3 R)-3- hydroxycyclohexyl]- 5- (2- methylnonan- 2- yl) 70434-92-3 C H O C H H H H Synonym: Cannabicyclohexanol phenol 22 36 2 2 5 CAS Molecular Common name Chemical name R1 R2 R3 R4 number Formula rel-2[(1 S,3 R)-3- hydroxycyclohexyl]- 5- (2- methyldecan- 2- yl) CP-47,497-C9 - C H O C H H H H phenol 23 38 2 3 7 rel-2- ((1 R,2 R,5 R)-5- hydroxy- 2- (3- hydroxypropyl)cyclohexyl)- 3-hydroxy CP-55,940 83003-12-7 C H O CH H H 5-(2- methyloctan- 2- yl)phenol 24 40 3 3 propyl rel-2- [(1 S,3 R)-3- hydroxy-5,5-dimethylcyclohexyl]- 5- (2- Dimethyl CP-47,497-C8 - C H O C H CH CH H methylnonan-2- yl)phenol 24 40 2 2 5 3 3 c) Aminoalkylindoles i) Naphthoylindoles 1' R R3' R2' O N CAS Molecular Common name Chemical name R1’ R2’ R3’ number Formula [1-[(1- methyl- 2- piperidinyl)methyl]- 1 H-indol- 3- yl]- 1- 1-methyl-2- AM-1220 137642-54-7 C H N O H H naphthalenyl-methanone 26 26 2 piperidinyl -

Synthetic Cannabinoids Synthetic Cannabinoids-1

Synthetic Cannabinoids-1 Synthetic Cannabinoids ™ (HEIA ) For the detection of JWH-018, JWH-073, AM-2201 & their major metabolites Homogeneous Enzyme Immunoassay (HEIA™) K2-3 K2-2 K2-1 Assay Specifications Sensitivity: 100% LC-MS/MS Confirmation Specificity: 87.5% Methodology: Homogeneous Enzyme Immunoassay Accuracy: 96.9% Positive Negative Cutoff: 10 ng/mL HEIA Positive 48 2* Calibrator: JWH-018 N-pentanoic acid (10 ng/mL) Negative 0 14 *2 discrepant specimens that screened negative were borderline negative at 10 ng/mL cutoff. AB-PINACA ADB-PINACA UR-144 XLR11 JWH-018 JWH-073 AM-2201 Immunalysis now offers three distinct Synthetic Cannabinoid Homogeneous Enzyme Immunoassays (HEIA™) Cross-Reactivity N/D = Cross-Reactivity < 0.05% for the detection of Synthetic Cannabinoids in urine. Our assays, geared towards the detection of JWH-018, JWH-073, AM-2201, UR-144, XLR11 and their metabolites, are now complemented by a NEW assay targeted Analyte Analyte Concentration JWH-018 N-pentanoic acid Cross-Reactivity at the next generation, AB-PINACA and ADB-PINACA compounds found in the current Spice or K2 products. (ng/mL) Equivalent (ng/mL) (%) Together, these assays detect Schedule I controlled substances and provide the most comprehensive screening JWH-018 N-pentanoic acid 10 10 100 tool for your automated chemistry analyzer. JWH-018 N-(5-hydroxypentyl) 15 10 67 JWH-018 4-hydroxyindole 135 10 7.4 JWH-018 5-hydroxyindole 40 10 25 AM-2201 N-(4-hydroxypentyl) 12 10 83 Liquid Stable, Ready to Use AM-2201 6-hydroxyindole 20 10 50 JWH-073 N-(4-hydroxybutyl) -

2 Spice English Presentation

Spice Spice contains no compensatory substances Специи не содержит компенсационные вещества Spice is a mix of herbs (shredded plant material) and manmade chemicals with mind-altering effects. It is often called “synthetic marijuana” because some of the chemicals in it are similar to ones in marijuana; but its effects are sometimes very different from marijuana, and frequently much stronger. It is most often labeled “Not for Human Consumption” and disguised as incense. Eliminationprocess • The synthetic agonists such as THC is fat soluble. • Probably, they are stored as THC in cell membranes. • Some of the chemicals in Spice, however, attach to those receptors more strongly than THC, which could lead to a much stronger and more unpredictable effect. • Additionally, there are many chemicals that remain unidentified in products sold as Spice and it is therefore not clear how they may affect the user. • Moreover, these chemicals are often being changed as the makers of Spice alter them to avoid the products being illegal. • To dissolve the Spice crystals Acetone is used endocannabinoids synhtetic THC cannabinoids CB1 and CB2 agonister Binds to cannabinoidreceptor CB1 CB2 - In the brain -in the immune system Decreased avtivity in the cell ____________________ Maria Ellgren Since some of the compounds have a longer toxic effects compared to naturally THC, as reported: • negative effects that often occur the day after consumption, as a general hangover , but without nausea, mentally slow, confused, distracted, impairment of long and short term memory • Other reports mention the qualitative impairment of cognitive processes and emotional functioning, like all the oxygen leaves the brain. -

Retrospective Identification of Synthetic Cannabinoids in Forensic Toxicology Casework Using Archived High Resolution Mass Spectrometry Data Author(S): Alex J

The author(s) shown below used Federal funding provided by the U.S. Department of Justice to prepare the following resource: Document Title: Retrospective Identification of Synthetic Cannabinoids in Forensic Toxicology Casework using Archived High Resolution Mass Spectrometry Data Author(s): Alex J. Krotulski, Ph.D., Amanda L.A. Mohr, MSFS, D-ABFT-FT, Barry K. Logan, Ph.D., F-ABFT Document Number: 255668 Date Received: November 2020 Award Number: 2017-R2-CX-0021 This resource has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. This resource is being made publically available through the Office of Justice Programs’ National Criminal Justice Reference Service. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Title: Retrospective Identification of Synthetic Cannabinoids in Forensic Toxicology Casework using Archived High Resolution Mass Spectrometry Data Authors: Alex J Krotulski, PhD, Amanda LA Mohr, MSFS, D-ABFT-FT, and Barry K Logan, PhD, F-ABFT Organization: Center for Forensic Science Research and Education at the Fredric Rieders Family Foundation, Willow Grove, PA, USA Award Number: 2017-R2-CX-0021 This resource was prepared by the author(s) using Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Abstract Since 2008, synthetic cannabinoids have continued to proliferate and challenge the forensic science community due to rapid appearance and diverse chemistry. -

How Present Synthetic Cannabinoids Can Help Predict Symptoms in the Future

MOJ Toxicology Mini Review Open Access How present synthetic cannabinoids can help predict symptoms in the future Abstract Volume 2 Issue 1 - 2016 New synthetic cannabinoids appear regularly in the illicit drug market, often in response to Melinda Wilson-Hohler,1 Wael M Fathy,2 legal restrictions. These compounds are characterized by increasing binding affinities (Ki) 3 to CB1 and CB2 receptors. Increasing affinity to CB receptors can occur by substitution of a Ashraf Mozayani 1Consultant, The Forensic Sciences, USA halogen on the terminal position of the pentyl chain of the classical synthetic cannabinoids. 2Post-Doctoral Fellowship, Texas Southern University, USA & Fluorination of the aliphatic side chain of established cannabinoid agonists is a popular Toxicologist, Ministry of Justice, Egypt pathway of modifying existing active drugs and synthesizing novel drugs to increase 3Professor, Barbara Jordan-Mickey Leland School of Public potency. Biological impacts of these compounds that have been reported include seizures, Affairs, Texas Southern University, USA body temperature losses that may lead to cardiac distress, as well as cases reporting delirium and severe neural incapacities. These symptoms have been reported in case Correspondence: Ashraf Mozayani, Executive Director of reports with evidence that like their cannabinoid counterparts, these compounds distribute Forensic Science and Professor, Barbara Jordan-Mickey Leland post-mortem into a variety of tissues, especially adipose tissue. Researchers have detected School of Public Affairs, Texas Southern University, USA, and identified certain synthetic cannabinoid compounds on botanicals using a variety of Tel17132526556, Email [email protected] separation and detection systems such as GC-FID and GC-MS, as well as LC-MS/MS and NMR. -

Model Scheduling New/Novel Psychoactive Substances Act (Third Edition)

Model Scheduling New/Novel Psychoactive Substances Act (Third Edition) July 1, 2019. This project was supported by Grant No. G1799ONDCP03A, awarded by the Office of National Drug Control Policy. Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the Office of National Drug Control Policy or the United States Government. © 2019 NATIONAL ALLIANCE FOR MODEL STATE DRUG LAWS. This document may be reproduced for non-commercial purposes with full attribution to the National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws. Please contact NAMSDL at [email protected] or (703) 229-4954 with any questions about the Model Language. This document is intended for educational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice or opinion. Headquarters Office: NATIONAL ALLIANCE FOR MODEL STATE DRUG 1 LAWS, 1335 North Front Street, First Floor, Harrisburg, PA, 17102-2629. Model Scheduling New/Novel Psychoactive Substances Act (Third Edition)1 Table of Contents 3 Policy Statement and Background 5 Highlights 6 Section I – Short Title 6 Section II – Purpose 6 Section III – Synthetic Cannabinoids 13 Section IV – Substituted Cathinones 19 Section V – Substituted Phenethylamines 23 Section VI – N-benzyl Phenethylamine Compounds 25 Section VII – Substituted Tryptamines 28 Section VIII – Substituted Phenylcyclohexylamines 30 Section IX – Fentanyl Derivatives 39 Section X – Unclassified NPS 43 Appendix 1 Second edition published in September 2018; first edition published in 2014. Content in red bold first added in third edition. © 2019 NATIONAL ALLIANCE FOR MODEL STATE DRUG LAWS. This document may be reproduced for non-commercial purposes with full attribution to the National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws. -

Appendix-2Final.Pdf 663.7 KB

North West ‘Through the Gate Substance Misuse Services’ Drug Testing Project Appendix 2 – Analytical methodologies Overview Urine samples were analysed using three methodologies. The first methodology (General Screen) was designed to cover a wide range of analytes (drugs) and was used for all analytes other than the synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists (SCRAs). The analyte coverage included a broad range of commonly prescribed drugs including over the counter medications, commonly misused drugs and metabolites of many of the compounds too. This approach provided a very powerful drug screening tool to investigate drug use/misuse before and whilst in prison. The second methodology (SCRA Screen) was specifically designed for SCRAs and targets only those compounds. This was a very sensitive methodology with a method capability of sub 100pg/ml for over 600 SCRAs and their metabolites. Both methodologies utilised full scan high resolution accurate mass LCMS technologies that allowed a non-targeted approach to data acquisition and the ability to retrospectively review data. The non-targeted approach to data acquisition effectively means that the analyte coverage of the data acquisition was unlimited. The only limiting factors were related to the chemical nature of the analyte being looked for. The analyte must extract in the sample preparation process; it must chromatograph and it must ionise under the conditions used by the mass spectrometer interface. The final limiting factor was presence in the data processing database. The subsequent study of negative MDT samples across the North West and London and the South East used a GCMS methodology for anabolic steroids in addition to the General and SCRA screens. -

Cannabinoid-Like Effects of Five Novel Carboxamide Synthetic Cannabinoids T ⁎ Michael B

Neurotoxicology 70 (2019) 72–79 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Neurotoxicology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/neuro Full Length Article Cannabinoid-like effects of five novel carboxamide synthetic cannabinoids T ⁎ Michael B. Gatch , Michael J. Forster Department of Pharmacology and Neuroscience, Center for Neuroscience Discovery, University of North Texas Health Science Center, 3500 Camp Bowie Blvd, Fort Worth, TX, 76107-2699, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: A new generation of novel cannabinoid compounds have been developed as marijuana substitutes to avoid drug Drug discrimination control laws and cannabinoid blood tests. 5F-MDMB-PINACA (also known as 5F-ADB, 5F-ADB-PINACA), MDMB- Locomotor activity CHIMICA, MDMB-FUBINACA, ADB-FUBINACA, and AMB-FUBINACA (also known as FUB-AMB, Rat MMB-FUBINACA) were tested for in vivo cannabinoid-like effects to assess their abuse liability. Locomotor Mouse activity in mice was tested to screen for locomotor depressant effects and to identify behaviorally-active dose Abuse liability ranges and times of peak effect. Discriminative stimulus effects were tested in rats trained to discriminate Δ9- tetrahydrocannabinol (3 mg/kg, 30-min pretreatment). 5F-MDMB-PINACA (ED50 = 1.1 mg/kg) and MDMB- CHIMICA (ED50 = 0.024 mg/kg) produced short-acting (30 min) depression of locomotor activity. ADB-FUBINACA (ED50 = 0.19 mg/kg), and AMB- FUBINACA (ED50 = 0.19 mg/kg) depressed locomotor activity for 60–90 min; whereas MDMB-FUBINACA (ED50 = 0.04 mg/kg) depressed locomotor activity for 150 min. AMB-FUBINACA produced tremors at the highest dose tested. 5F-MDMB-PINACA (ED50 = 0.07), MDMB- CHIMICA (ED50 = 0.01 mg/kg), MDMB-FUBINACA (ED50 = 0.051 mg/kg), ADB-FUBINACA (ED50 = 0.075 mg/ 9 kg) and AMB-FUBINACA (ED50 = 0.029) fully substituted for the discriminative stimulus effects of Δ -THC following 15-min pretreatment. -

Alcohol and Drug Abuse Subchapter 9

Chapter 8 – Alcohol and Drug Abuse Subchapter 9 Regulated Drug Rule 1.0 Authority This rule is established under the authority of 18 V.S.A. §§ 4201 and 4202 which authorizes the Vermont Board of Health to designate regulated drugs for the protection of public health and safety. 2.0 Purpose This rule designates drugs and other chemical substances that are illegal or judged to be potentially fatal or harmful for human consumption unless prescribed and dispensed by a professional licensed to prescribe or dispense them and used in accordance with the prescription. The rule restricts the possession of certain drugs above a specified quantity. The rule also establishes benchmark unlawful dosages for certain drugs to provide a baseline for use by prosecutors to seek enhanced penalties for possession of higher quantities of the drug in accordance with multipliers found at 18 V.S.A. § 4234. 3.0 Definitions 3.1 “Analog” means one of a group of chemical components similar in structure but different with respect to elemental composition. It can differ in one or more atoms, functional groups or substructures, which are replaced with other atoms, groups or substructures. 3.2 “Benchmark Unlawful Dosage” means the quantity of a drug commonly consumed over a twenty-four-hour period for any therapeutic purpose, as established by the manufacturer of the drug. Benchmark Unlawful dosage is not a medical or pharmacologic concept with any implication for medical practice. Instead, it is a legal concept established only for the purpose of calculating penalties for improper sale, possession, or dispensing of drugs pursuant to 18 V.S.A.