Hoover's FBI the Inside Story by Hoover's Trusted Lieutenant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Was Lee Harvey Oswald in North Dakota

Chapter 28 Lee Harvey Oswald; North Dakota and Beyond John Delane Williams and Gary Severson North Dakota would become part of the JFK assassination story subsequent to a letter, sent by Mrs. Alma Cole to President Johnson. That letter [1] follows (the original was in Mrs. Cole’s handwriting): Dec 11, 1963 President Lyndon B. Johnson Dear Sir, I don’t know how to write to you, and I don’t know if I should or shouldn’t. My son knew Lee Harvey Oswald when he was at Stanley, North Dakota. I do not recall what year, but it was before Lee Harvey Oswald enlisted in the Marines. The boy read communist books then. He told my son He had a calling to kill the President. My son told me, he asked him. How he would know which one? Lee Harvey Oswald said he didn’t know, but the time and place would be laid before him. There are others at Stanley who knew Oswald. If you would check, I believe what I have wrote will check out. Another woman who knew of Oswald and his mother, was Mrs. Francis Jelesed she had the Stanley Café, (she’s Mrs. Harry Merbach now.) Her son, I believe, knew Lee Harvey Oswald better than mine did. Francis and I just thought Oswald a bragging boy. Now we know different. We told our sons to have nothing to do with him (I’m sorry, I don’t remember the year.) This letter is wrote to you in hopes of helping, if it does all I want is A Thank You. -

"Oracles": 2009

Oracles Previous postings from the William Thomas Sherman Info Page 2009. By William Thomas Sherman 1604 NW 70th St. Seattle, WA 98117 206-784-1132 [email protected] http://www.gunjones.com ~~~~~~*~~~~~~ TENETS *If we ever experienced a problem anywhere, it came about, in some degree, due to certain wrong assumptions, either co-present with, or just prior to the given problem’s actually taking place. * Unless you believe in God, the One, and or the infinite, every assumption is contingent. * PROCESS (or if you prefer spirit, or activity) PRECEDES IMAGE. Image may, to some extent, (and sometimes almost perfectly) represent process. But process is always superior to and always more real than image. If process precedes image this might suggest also that mind precedes matter and energy. * Everything we believe, or say we know, is based on a factual or value judgment. Both kinds of judgment always entail the other to some extent, and nothing can be known or exists for us without them. * No fact or purported fact is true or false without someone to assert and believe it to be such. If an assertion or claim is deemed true or false then, and we are thorough, we should ask who is it that says so (or has said so), and what criteria are (were) they using? There is no such thing as "faceless" truth or reality -- at least none we are capable of knowing. * You can't escape reason. If you aren't rational yourself, someone else will be rational for you; nor do their intentions toward you need to be friendly or benevolent. -

Kennedy Assassination

Page B-4 THE POST, Frederick, Maryland Friday, November 23, 1973 The Tragic Days Kennedy Assassination - By ROBERT E. FORD Associated Press Writer DALLAS, Tex. (AP) — "My God! I am hit!" the first man triree years oetore. cried. Yet some in Dallas were "Oh, no, no, no! My God, fearful. they are going to kill us all!" The Secret Service had asked cried the second man. for extra Dallas policemen to And so began 48 hours and 37 help. Chief Jesse Curry gave minutes of trauma and tragedy the Service all it asked and a decade ago . called in still more men. The dead: Some thought the militant President John F. Kennedy. right wing might try a demon- Police officer J. D. Tippit. stration. United Nations Am- Lee Harvey Oswald. bassador Adlai Stevenson had The wounded: been spat upon here a month Texas Gov. John B., Con- before. Scurrilous handbills had nally. been circulated on the eve of A decade ago in Lime, but Kennedy's arrival. still vivid in the mind of a na- And there were all those tion. Still terrible, the details of thousands of windows in the that November day in Dallas ... tall buildings from which an as- The air was sharp and a sault could he launched. bright sun beamed out of a The motorcade crawled west cloudless sky when Air Force. on Main. Turn right. One block One landed at Dallas' Love along Houston. Left onto Elm Field at 11:37 a.m. on Nov. 22, at a nondescript old brick 1963. structure seven stories high. -

Lobster 69 Summer 2015

www.lobster-magazine.co.uk Summer 2015 The View from the Bridge Lobster by Robin Ramsay Julian Assange and the European Arrest Warrant by Bernard Porter 69 Holding pattern by Garrick Alder The CIA, torture, history and American exceptionalism by Michael Carlson Chauncey Holt and the three ‘tramps’ on Dealey Plaza by Robin Ramsay JFK’s assassination: two stories about fingerprints by Garrick Alder Apocryphilia by Simon Matthews Book Reviews The Secret War Between the Wars by Kevin Quinlan Reviewed by Robin Ramsay Method and Madness: The hidden story of Israel’s assaults on Gaza by Norman G. Finkelstein Reviewed by Robin Ramsay The News Machine: Hacking,The Untold Story by James Hanning with Glenn Mulcaire Reviewed by Tom Easton The JFK Assassination Diary by Edward Jay Epstein Reviewed by Robin Ramsay Deception in High Places by Nicholas Gilby Reviewed by Robin Ramsay The 2001 Anthrax Deception: The Case for a Domestic Conspiracy by Graeme MacQueen Reviewed by Tom Easton That option no longer exists: Britain 1974-76 by John Medhurst Reviewed by Robin Ramsay The American deep state: Wall Street, big oil and the attack on U.S. democracy by Peter Dale Scott Reviewed by Robin Ramsay The EU: A Corporatist Racket: How the European Union was created by global corporatism for global corporatism, by David Barnby Reviewed by Robin Ramsay Race to Revolution: The United States and Cuba During Slavery and Jim Crow, by Gerald Horne Reviewed by Dr. T. P. Wilkinson Sailing Close To The Wind: Confessions of a Labour Loyalist, by Dennis Skinner and Kevin Maguire Reviewed by John Newsinger www.lobster-magazine.co.uk The view from the bridge Robin Ramsay Kincora, Blunt and......JFK? Because it is difficult to distinguish the shit from the shinola among the allegations and rumours, thus far I have avoided trying to make sense of the Kincora scandal’s place in the Elm House-Savile-paedos-in-high-places thicket. -

Assassination: Truth Compromised? the GLOBAL VILLAGE PROJECT ©

COLLECTORS' EDITION THE J F K assassination: truth compromised? THE GLOBAL VILLAGE PROJECT © CONTENTS profile: PAGE 10/COVER JFK Who killed JFK? Why was President Kennedy killed? Was President Kennedy's murder thresult of a calculated conspiracy? The Global Village Project addresses these much-debated by analyzing and reviewing the 60's evidence, conspiracy theories, and controversies surrounding the Kennedy assassination. facets: PAGE 61/DOES HISTORY REPEAT ITSELF? A look at the similarities that exist between the assassinations of Am rican Presidents Abraham Lincoln and John F. Kennedy. PAGE 64/THE MARRIAGE OF ABSTRACT AND ABSOLUTE might come across as "artsy- fartsy" and taking monstrous liberties with poetic license - but, so what! PAGE 67/THE ME IACRACY OF THE REAGAN PRESIDENCY highlights or lowlights the tempest-tost vitriol o the Reagan Presidency. Media was to Reagan as a violin was to Heifetz: a tool to be mastere PAGE 80/COLLEC i E OWNERSHIP: THE LIGHT AT THE END OF THE TUNNEL. With the collapse of the Soviet economy, the United States, in certain industrial centres, is experimenting with 'Collective Ownership" of industry. Go figure! We illustrate a working model. PAGE 85/INTELLIi ENCE TESTS? WHAT INTELLIGENCE TESTS? Is the idea of genetic inheritance of intelli ence dwindling? Popular belief shows that the "yeas" have it. PAGE 88/THE CA ADIAN PERSPECTIVE gives you the chance to sound-off on the many social/political/ethic questions and dilemmas that surround us as Canadians and global villagers. Departments: Opinions & Things - 99/Simply Cerebral or Grey Matter or Think About Publisher : ditor: (J.), Frank Konto Syntax Edi or: Chris J. -

The Rambler Man

THE RAMBLER MAN One wouldn't consider it much of an obituary. A life reduced to eleven paragraphs in The Dallas Morning News. The commentary is not remarkable for a person of the prominence of ex-deputy sheriff Roger Craig. Not for the employee the Dallas County sheriff's office proclaimed "Man of the Year" in 1960. Roger Craig's popularity grew among Kennedy assassination investigators when he maintained he witnessed an event involving a Nash Rambler station wagon in Dealey Plaza on November 22, 1963. He spoke freely about the incident, disputed details of the assassination with superior officers, lost his job, aided in Jim Garrison's probe of Clay Shaw, became the friend of several researchers' and died by his own hand on May 15, 1975. Sadly, Craig's father discovered the body in a back bedroom of the small house on Luna Road in Dallas, this a few minutes after the old man had returned from mowing his lawn. There was a note. The physical and mental anguish resulting from a car wreck in 1973 and a shotgun wound to the shoulder sustained in 1974 was too much. Roger was sorry for what he had to do but he just "couldn't stand the pain." In the quiet of the Dallas Public Library I reviewed the eighteen year old obituary. I remembered the story of Craig's sighting of the Nash Rambler station wagon in front of the Texas School Book Depository on November 22nd. His account became important when a claim arose that Marina Oswald's friend and confidant, Ruth Paine, owned a similar vehicle. -

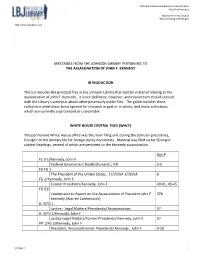

Materials from the Johnson Library Pertaining to the Assassination of John F

National Archives and Records Administration http://archives.gov National Archives Catalog https://catalog.archives.gov http://www.lbjlibrary.org MATERIALS FROM THE JOHNSON LIBRARY PERTAINING TO THE ASSASSINATION OF JOHN F. KENNEDY INTRODUCTION This list includes the principal files in the Johnson Library that contain material relating to the assassination of John F. Kennedy. It is not definitive, however, and researchers should consult with the Library's archivists about other potentially useful files. The guide includes those collections which have been opened for research in part or in whole, and those collections which are currently unprocessed or unavailable. WHITE HOUSE CENTRAL FILES (WHCF) This permanent White House office was the main filing unit during the Johnson presidency, though not the primary file for foreign policy documents. Material was filed under 60 major subject headings, several of which are pertinent to the Kennedy assassination. Box # FE 3-1/Kennedy, John F. Federal Government Deaths/Funerals, JFK 3-5 EX FG 1 The President of the United States, 11/22/64-1/10/64 9 FG 2/Kennedy, John F. Former Presidents/Kennedy, John F. 40-41, 43-45 FG 635 Commission to Report on the Assassination of President John F. 376 Kennedy (Warren Commission) JL 3/FG 1 Justice - Legal Matters/Presidential Assassinations 37 JL 3/FG 2/Kennedy, John F. Justice Legal Matters/Former Presidents/ Kennedy, John F. 37 PP 1/FG 2/Kennedy, John F. President, Personal/Former Presidents/ Kennedy, John F. 9-10 02/28/17 1 National Archives and Records Administration http://archives.gov National Archives Catalog https://catalog.archives.gov http://www.lbjlibrary.org (Cross references and letters from the general public regarding the assassination.) PR 4-1 Public Relations - Support after the Death of John F. -

The Death of a President, Minority of One, Jan 1964

This document is online at: http://ratical.org/ratville/JFK/DeathOfPres.html “In the Coils of the Spider” THE DEATH OF A PRESIDENT A review of the many inconsistencies and mysteries involved in the investigation of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. The reaction of a stunned world: Was it a conspiracy? by Eric Norden THE MINORITY OF ONE January 1964, pp. 16-23 “Woe to the hand that shed this costly blood! . A curse shall light upon the limbs of men; Domestic fury and fierce civil strife shall comber all the parts of Italy; And Caesar’s spirit, ranging for revenge With Ate by his side come hot from hell, Shall in these confines with a monarch’s voice Cry havoc, and let slip the dogs of war.” —Julius Caesar, Act III, Scene I When the mighty fall, they do not fall alone. The sniper’s bullet that snuffed out the life of John F. Kennedy on a bright autumn noon in Dallas, Texas has shaken the United States of America to its moral and political foundations. As the fabric of John Kennedy’s life shattered and dissolved into nothingness, the continuity and stability of American political life suffered a wound as grave, and perhaps as irrevocable. The murder of John Kennedy was a personal, human tragedy of monumental proportions; his death may portend disaster for all men. If John Kennedy were an ordinary man, it would be possible to restrict our reaction to his death to grief. But the nature of his office and the circumstances of his death deny us even this solace. -

Evidence & Investigations

Evidence & Investigations Books - Articles - Videos - Collections - Oral Histories - YouTube - Websites Visit our Library Catalog for complete list of books, magazines, and videos. Books Bloomgarden, Henry S. The Gun: A "Biography" of the Gun that Killed John F. Kennedy. New York: Bantam Books, 1975. Bonner, Judy Whitson. Investigation of a Homicide; the Murder of John F. Kennedy. Droke House, 1969. Bugliosi, Vincent. Reclaiming History: the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2007. Chambers, G. Paul. Head Shot: the Science behind the John F. Kennedy Assassination. New York: Prometheus Books, 2010. Commission on Physical Sciences, Mathematics, and Applications. Report of the Committee on Ballistic Acoustics. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1982. Cutler, Robert Bradley. Two Flightpaths: Evidence of Conspiracy. Massachusetts: Minutemen Press, 1988. Curry, Jesse E. Retired Dallas Police Chief, Jesse Curry, Reveals His Personal JFK Assassination File. Dallas: 1969. Garrison, Jim. On the Trail of the Assassins: My Investigation and Prosecution of the Murder of President Kennedy. New York: Sheridan Square Press, 1988. Horn, Douglas P. Inside the Assassination Records Review Board: The U.S. Government's Final Attempt to Reconcile the Conflicting Medical Evidence in the Assassination of JFK. Falls Church, VA: 2009. Marcus, Raymond. The HSCA, the Zapruder Film and the Single-Bullet Theory. [S.l.]: Raymond Marcus, 1992. Meagher, Sylvia and Gary Owens. Master Index to the J.F.K. Assassination Investigations the reports and supporting volumes of the House Select Committee on Assassinations and the Warren Commission. New Jersey: Scarecrow Press, 1980. Rockefeller, Nelson A. Report to the President by the Commission on CIA Activities Within the United States. -

Some Observations Regarding the JFK Assassination

Some Observations Regarding the JFK Assassination By Wm. Thomas Sherman Last updated: 29 May 2017 The following are a series of casual commentaries carried on at my website http://www.gunjones.com, originally posted in 2008 and 2009, and which pertain to the assassination of Pres. John F. Kennedy. At my website, the subject of the scientifically verifiable existence of spirit people; such as what we normally think of as ghosts, demons, angels, etc., is a common theme and subject; so that my remarks and analysis of the JFK murder to some extent are tied in with that. While I certainly don’t expect that someone just being introduced to my work to readily or out of hand accept my hypothesis and claim regarding “spirit people,” let it at least be said here that I explore that same topic at greater length and depth at my website, and to which I would refer you for further explanation of where I am coming from.1 This said, my comments regarding Nov. 22, 1963 can, to a significant extent, can be assessed on their own merit without any reference or association to my asseverations with respect to spirit people; so that in this document before you are extracts from those website postings that focus exclusively on the Kennedy case. These observations of mine are fairly random, desultory, and as I said casual (including some occasionally humorous in purpose and character), and I don’t claim to be deeply informed expert on the JFK assassination but rather an amateur. However, using what facts and reasoning I do have available to me, I do think that some who are more informed on the subject will, nevertheless, perhaps find some value in them; hence, my gathering them together in one document for their and others’ possible use and benefit. -

Curry Ex 5313

F1 (Rep . .-302 3-3-59) FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION Dote 11/25/63 Chief JESSE CURRY stated that the plan for removal of LEE HARVEY OSWALD from the Dallas City Jail to the Dallas County Jail, was left to the discretion of Homicide Captain WILL FRITZ, who was in charge of investigating the murder of Officer J . Z' . TIPPITT of the Dallas Police Department by OSWALD on November 22, 1963 and the murder of President JOIN F . KENNEDY and the shooting of Governor JOHN CONNALLY . He stated that FRITZ told him he planned to remove OSWALD sometime during the following day to the Dallas County Jail . fa stated that he did not specify any time and that was left to the discretion of FRITZ . He stated that FRITZ was' lncharge - a of the plans for removal of OSWALD to the Dallas County i Jail . ' Chief CURRY stated at no time did he give the press a specific time as to when OSWALD would be removed to the Dallas County Jail from the Dallas City Jail . He ~._ Is tatad on the night of November 23, he was asked by the ;- f +1,.epress when they should be back and he told them 10 ;00 next morning . He stated that he was tired and worn gout and that the press was tired . He stated that he did not at any time give the press a specific time as to when OSWALD would be removed at that time because he, himself, did not know . He stated that FRITZ was in charge of the plans of the removal of OSWALD to the Dallas County Jail and that the time was strictly up to FRITZ as to when he was to move him. -

Dealey Plaza Eyewitnesses

Dealey Plaza Eyewitnesses Books - Articles - Videos - Collections - Oral Histories - YouTube - Websites Visit our Library Catalog for complete list of books, magazines, and videos. Books Aynesworth, Hugh. November 22, 1963: Witness to History. Dallas: Brown Books, 2013. Brennan, Howard L. Eyewitness to History: The Kennedy Assassination as Seen by Howard L. Brennan. Waco, TX: Texian Press, 1987. Bugliosi, Vincent. Reclaiming History: The Assassination of President John F. Kennedy. New York: W.W. Norton, 2007. Connally, John B. In History's Shadow: An American Odyssey. New York: Hyperion, 1993. Connally, Nellie. From Love Field: Our Final Hours with President John F. Kennedy. New York: Rugged Land, 2003. Crenshaw, Charles A., Jens Hensen and Gary Shaw. JFK Conspiracy of Silence. New York: Signet, 1992. Curry, Jesse E. Retired Dallas Police Chief, Jesse Curry, Reveals His Personal JFK Assassination File. Dallas: 1969. Dallas Morning News. JFK Assassination: The Reporter’s Notes. Canada: Pediment, 2013. Hampton, Wilborn. Kennedy Assassinated! The World Mourns: A Reporter's Story. Cambridge, MA: Candlewick Press, 1997. Hill, Clint and Lisa McCubbin. Five Days in November. New York: Gallery Books, 2013. Hlavach, Laura. Reporting the Kennedy Assassination: Journalists Who Were There Recall Their Experiences. Dallas, TX: Three Forks Press, 1996. Oliver, Beverly. Nightmare in Dallas. Pennsylvania: Starburst Publishers, 1994. Read, Julian. JFK’s Final Hours in Texas: An Eyewitness Remembers the Tragedy and Its Aftermath. Austin: University of Texas at Austin, 2013. Smith, Merriman. The Murder of the Young President. Washington D.C.: United Press International, 1963. Sneed, Larry A. No More Silence: An Oral History of the Assassination of President Kennedy.