Elizabeth Cady Stanton's Address on Woman's Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Founding Mother The Seneca Falls Convention began a six decade career of women’s rights activism by Elizabeth Cady Stanton. “It has been said that I forged the thunderbolts and she fired them.” Elizabeth Cady Stanton on her partnership with Susan B. Anthony Young Susan B. Anthony Elizabeth Cady sometimes helped in the Stanton and Stanton household. “Susan daughter Harriot, stirs the pudding, Elizabeth 1856. Harriot stirs up Susan, and Susan would also become stirs up the world,” explained a leading advocate Elizabeth’s husband of women’s rights. Henry Stanton. Elizabeth Cady Stanton grew up in a home Project Gutenberg with twelve servants. Early in her marriage Cady Stanton had a more modest lifestyle in A Unique Partnership Seneca Falls, New York. Kenneth C. Zirkel When her children were older Cady Stanton toured eight months She has been called the “outstanding philosopher” of the each year as a paid lecturer. One winter she traveled forty to fifty women’s movement. Even in childhood Elizabeth Cady miles a day by sleigh, often in sub-zero temperatures, when west- Stanton had a passion for equality. In order to compete ern railroads were not running. with boys she studied the “books they read and the games they played,” beginning a lifelong habit of intellectual cu- riosity. Later, as the mother of seven children, she some- times felt like a “caged lioness.” Elizabeth wrote speeches and prepared arguments for her friend Susan B. Anthony Boston to deliver on the lecture circuit. As a young couple Elizabeth Cady Stanton and husband On the Road Henry lived for a time in Massa- chusetts, a center of nineteenth Cady Stanton took to the century reform. -

Darwin and the Women

COMMENT BOOKS & ARTS division of the “eight-hour husband” work- ing outside the home and the “fourteen-hour wife” within it. Feminist intellectual Charlotte Perkins Gilman drew on Darwin’s sexual- TTMANN/CORBIS selection theory to argue that women’s eco- BE nomic dependence on men was unnaturally skewing evolution to promote “excessive sex- ual distinctions”. She proposed that economic and reproductive freedom for women would restore female autonomy in choice of mate — which Darwin posited was universal in nature, except in humans — and put human evolutionary progress back on track. L LIB. OF CONGRESS; R: TIME LIFE PICTURES/GETTY; Darwin himself opposed birth control and Women’s advocates (left to right) Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Antoinette Brown Blackwell and Maria Mitchell. asserted the natural inferiority of human females. The adult female, he wrote in The EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY Descent of Man (1871), is the “intermediate between the child and the man”. Neverthe- less, appeals to Darwinist ideas by birth-con- trol advocates such as Margaret Sanger led Darwin and one critic to bemoan in 1917 that “Darwin was the originator of modern feminism”. Feminism in the late nineteenth century was marked by the racial and class politics the women of the era’s reform movements. Blackwell’s and Gilman’s views that women should work outside the home, for example, depended on Sarah S. Richardson relishes a study of how nineteenth- the subjugated labour of lower-class minor- century US feminists used the biologist’s ideas. ity women to perform household tasks. And Sanger’s birth-control politics appealed to contemporary fears of race and class ‘sui- wo misplaced narratives dominate physician Edward cide’. -

19Th Amendment Conference | CLE Materials

The 19th Amendment at 100: From the Vote to Gender Equality Center for Constitutional Law at The University of Akron School of Law Friday, Sept. 20, 2019 CONTINUING EDUCATION MATERIALS More information about the Center for Con Law at Akron available on the Center website, https://www.uakron.edu/law/ccl/ and on Twitter @conlawcenter 001 Table of Contents Page Conference Program Schedule 3 Awakening and Advocacy for Women’s Suffrage Tracy Thomas, More Than the Vote: The 19th Amendment as Proxy for Gender Equality 5 Richard H. Chused, The Temperance Movement’s Impact on Adoption of Women’s Suffrage 28 Nicole B. Godfrey, Suffragist Prisoners and the Importance of Protecting Prisoner Protests 53 Amending the Constitution Ann D. Gordon, Many Pathways to Suffrage, Other Than the 19th Amendment 74 Paula A. Monopoli, The Legal and Constitutional Development of the Nineteenth Amendment in the Decade Following Ratification 87 Keynote: Ellen Carol DuBois, The Afterstory of the Nineteth Amendment, Outline 96 Extensions and Applications of the Nineteenth Amendment Cornelia Weiss The 19th Amendment and the U.S. “Women’s Emancipation” Policy in Post-World War II Occupied Japan: Going Beyond Suffrage 97 Constitutional Meaning of the Nineteenth Amendment Jill Elaine Hasday, Fights for Rights: How Forgetting and Denying Women’s Struggles for Equality Perpetuates Inequality 131 Michael Gentithes, Felony Disenfranchisement & the Nineteenth Amendment 196 Mae C. Quinn, Caridad Dominguez, Chelsea Omega, Abrafi Osei-Kofi & Carlye Owens, Youth Suffrage in the United States: Modern Movement Intersections, Connections, and the Constitution 205 002 THE CENTER FOR CONSTITUTIONAL LAW AT AKRON th The 19 Amendment at 100: From the Vote to Gender Equality Friday, September 20, 2019 (8am to 5pm) The University of Akron School of Law (Brennan Courtroom 180) The focus of the 2019 conference is the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. -

Wesleyan Chapel

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Women’s Rights Women’s Rights National Historical Park The Wesleyan Chapel 72 years after ‘The Declaration of Independence’ was signed, 300 people met at the Wesleyan Chapel to protest the laws and customs that discriminated against women. Here they signed a new document, ‘The Declaration of Sentiments’. Both of these documents challenged the status quo and both of them were just the beginning of a years-long struggle for freedom. It would take another 72 years after the convention before women were given the right to vote. Like the movement, the chapel underwent many changes, but its significance as a cradle of liberty was not forgotten. Origins In 1843 a small group of reform-minded Seneca Falls residents declared they were forming a Wesleyan Methodist church. This followed a national trend that had begun several years earlier when antislavery members of the Meth- odist Episcopal Church decided to break away and organize a new church that condemned slavery. The Seneca Falls Wesleyan Methodists set to work building their new church, and by October 1843 the building was completed. An article about the church published in the True Wesleyan described its appearance: “[The Cha- pel is] of brick, 44 x 64, with a gallery on three sides, and is well finished, though, as it should be, it is plain.” The spirit of reform that inspired the Seneca Falls First Woman’s Rights Convention was already present in the early use of the chapel. Antoinette Brown, the first ordained female minister in America, spoke about the violence in Kansas Territory at the chapel in May 1855. -

The Journey to Seneca Falls: Mary Wollstonecraft, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the Legal Emancipation of Women

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of St. Thomas, Minnesota University of St. Thomas Law Journal Volume 10 Article 9 Issue 4 Spring 2013 2013 The ourJ ney to Seneca Falls: Mary Wollstonecraft, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the Legal Emancipation of Women Charles J. Reid Jr. [email protected] Bluebook Citation Charles J. Reid, Jr., The Journey to Seneca Falls: Mary Wollstonecraft, lE izabeth Cady Stanton and the Legal Emancipation of Women, 10 U. St. Thomas L.J. 1123 (2013). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UST Research Online and the University of St. Thomas Law Journal. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLE THE JOURNEY TO SENECA FALLS: MARY WOLLSTONECRAFT, ELIZABETH CADY STANTON AND THE LEGAL EMANCIPATION OF WOMEN DR. CHARLES J. REID, JR.* ABSTRACT “[T]he star that guides us all,” President Barack Obama declared in his Second Inaugural, is our commitment to “human dignity and justice.”1 This commitment has led us “through Seneca Falls and Selma and Stone- wall”2 towards the equality that we enjoy today. This Article concerns the pre-history to the Seneca Falls Convention of Women’s Rights, alluded to by President Obama. It is a journey that began during the infancy of the common law in medieval England. It leads through the construction, by generations of English lawyers and religious figures, of a strong and im- posing monolith of patriarchal rule. By marriage women lost their indepen- dent legal personality and were, for purposes of law, incorporated into their husband in accord with the legal doctrine known as coverture. -

The Women's Suffrage Movement

Name _________________________________________ Date __________________ The Women’s Suffrage Movement Part 1 The Women’s Suffrage Movement began with the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848. The idea for the Convention came from two women: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott. Both were concerned about women’s issues of the time, specifically the fact that women did not have the right to vote. Stanton felt that this was unfair. She insisted that women needed the power to make laws, in order to secure other rights that were important to women. The Convention was designed around a document that Stanton wrote, called the “Declaration of Sentiments”. Using the Declaration of Independence as her guide, she listed eighteen usurpations, or misuses of power, on the part of men, against women. Stanton also wrote eleven resolutions, or opinions, put forth to be voted on by the attendees of the Convention. About three hundred people came to the Convention, including forty men. All of the resolutions were eventually passed, including the 9th one, which called for women’s suffrage, or the right for women to vote. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott signed the Seneca Falls Declaration and started the Suffrage Movement that would last until 1920, when women were finally granted the right to vote by the 19th Amendment to the Constitution. 1. What event triggered the Women’s Suffrage Movement? ___________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________ 2. Who were the two women -

The Seneca Falls Convention

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archivo Digital para la Docencia y la Investigación END OF DEGREE PROJECT THE ORIGINS OF WOMEN’S RIGHTS MOVEMENT IN THE UNITED STATES: THE SENECA FALLS CONVENTION Anne Ruiz Ulloa Translation & Interpreting 2018-2019 Supervisor: Jose Mª Portillo Valdés Department of Contemporary History Abstract: In the 19th century, women had very limited or almost inexistent rights. They lived in a male dominated world where they had restricted access to many fields and they were considered to be an ornament of their husband in public life, and as a domestic agent to the interior of the family, as the Spanish contemporary expression ángel del hogar denotes. In the eyes of the law, they were civilly dead. They were considered fragile and delicate, because they were dependent on a man from birth to death. Tired of being considered less than their male companions, a women’s rights movement emerged in the small town of Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848. Women gathered for the first time in history at the Wesleyan Chapel to discuss women’s rights and to find a solution to the denigration they had suffered by men and society during the years. Around 300 people gathered in Seneca Falls, both men and women. As an attempt to amend the wrongs of men, these women created the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments, a document based on the Declaration of Independence, expressing their discontent with how the society had treated them and asking for a change and equal rights, among which there was the right for suffrage. -

Seneca Falls Convention

Seneca Falls Convention http://www.npg.si.edu/col/seneca/senfalls1.htm The seed for the first Woman's Rights Convention was planted in 1840, when Elizabeth Cady Stanton met Lucretia Mott at the World Anti- Slavery Convention in London. The conference had refused to seat Mott and other women delegates from America because of their sex. Stanton, the young bride of an antislavery agent, and Mott, a Quaker preacher and veteran of reform, talked then of calling a convention to address the condition of women. Eight years later, it came after a spontaneous social event. In July 1848, Mott was visiting her sister, Martha C. Wright, in Waterloo, New York. Stanton, now the restless mother of three small sons, was living in nearby Seneca Falls. A social visit brought together Mott, Stanton, Wright, Mary Ann McClintock, and Jane Hunt. All except Stanton were Quakers. Quakers (or Friends) were strong supporters of abolition and also afforded women some measure of equality. All five women were well acquainted with antislavery and temperance meetings. Fresh in their minds was the April passage of the long-deliberated New York Married Woman's Property Rights Act, a significant but far from comprehensive piece of legislation. The time had come, Stanton argued, for women's wrongs to be laid before the public, and women themselves must shoulder the responsibility. Before the afternoon was out, the women decided on a call for a convention "to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of woman." To Stanton fell the task of drawing up the Declaration of Sentiments that would define the meeting. -

Elizabeth Cady Stanton “Paved the Path for the Passage of the 19Th Amendment” November 12, 1815—October 26, 1902

Elizabeth Cady Stanton “Paved the Path for the Passage of the 19th Amendment” November 12, 1815—October 26, 1902 Elizabeth Cady Stanton was born in Johnstown, New York on November 12, 1815 to one of the city’s most promi- nent and respected couples. As a child, her father showed clear preference for his son over Stanton, so from a young age she showed the determination to excel in typically “male” fields of the time. In 1832, Stanton graduated from Emma Willard’s Troy Female Seminary, then becoming an active member of the abolitionist, temperance, and women’s rights movements through her cousin, reformer Gerrit Smith. In 1840, Stanton married another reformer, Henry Stanton, and they immediately travelled to the World’s Anti-Slavery Convention in London, where she and several other women objected their exclusion from the conference. After their time in London, the Stantons returned to Seneca Falls, New York. In July 1848, Stanton, Lucretia Mott, and several other women convened the Seneca Falls Convention. Together, those in attendance wrote the “Declaration of Sentiments” and spearheaded the movement to propose women be granted suffrage. Stanton continued to be a prolific writer and lecturer on women’s rights and other reform topics, and after meeting Susan B. Anthony in the early 1850s, she became one of the national leaders promoting women’s rights, especially the right to vote. During the Civil War, Stanton focused on abolition work, but after the end of the war, she became even more ardent in her work supporting women’s suffrage, working with Susan B. -

Elizabeth Cady Stanton Biography (1815–1902) Elizabeth Cady

Elizabeth Cady Stanton Biography (1815–1902) Elizabeth Cady Stanton was an early leader of the woman's rights movement, writing the Declaration of Sentiments as a call to arms for female equality. Who Was Elizabeth Cady Stanton? Elizabeth Cady Stanton was an abolitionist and leading figure of the early woman's movement. An eloquent writer, her Declaration of Sentiments was a revolutionary call for women's rights across a variety of spectrums. Stanton was the president of the National Woman Suffrage Association for 20 years and worked closely with Susan B. Anthony. Early Life Elizabeth Cady Stanton was born on November 12, 1815, in Johnstown, New York. The daughter of a lawyer who made no secret of his preference for another son, she early showed her desire to excel in intellectual and other "male" spheres. She graduated from Emma Willard's Troy Female Seminary in 1832, and then was drawn to the abolitionist, temperance and women's rights movements through visits to the home of her cousin, the reformer Gerrit Smith. In 1840, Elizabeth Cady Stanton married a reformer Henry Stanton (omitting “obey” from the marriage oath), and they went at once to the World's Anti-Slavery Convention in London, where she joined other women in objecting to their exclusion from the assembly. On returning to the United States, Stanton and Henry had seven children while he studied and practiced law, and eventually, they settled in Seneca Falls, New York. Women's Rights Movement With Lucretia Mott and several other women, Stanton held the famous Seneca Falls Convention in July 1848. -

Iroquois Native American Cultural Influences in Promoting Women's

Iroquois Native American Cultural Influences in Promoting Women’s Rights Ideologies Leading Up to the First Women’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls on the 19th and 20th of July, 1848 Willow Michele Hagan To what extent did Iroquois Native American culture and policies influence the establishment of the first ever women’s rights convention at Seneca Falls on the 19th and 20th of July, 1848? Abstract In Iroquois culture women have always shared equal treatment with men. They regard women with respect and authority; women can participate in equal labor and can own their own property. With these ideals so close in proximity to Seneca Falls, to what extent did Iroquois Native American culture and policies influence the establishment of the Seneca Falls Convention and the arguments for women’s rights it proposed? To answer this question, Iroquois relationships between women’s rights activists and other leaders in American society will be examined; including the spread of matrilineal thought into the minds of those who had ties to the Iroquois, predominantly with the leaders of the Seneca Falls Convention. The proposals put forth by the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments will also be addressed to look at the parallels between the thoughts promoted for women’s rights and those ideologies of Iroquois culture. Newspaper articles, as well as other primary and secondary sources, will be consulted in order to interpret this relationship. Through the exploration of the association between Iroquois culture and the Seneca Falls Convention, it can be determined that the culture of the Iroquois did have influence over the Seneca Falls Convention. -

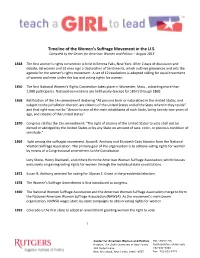

Timeline of the Women's Suffrage Movement in the U.S

Timeline of the Women’s Suffrage Movement in the U.S. Compiled by the Center for American Women and Politics – August 2014 1848 The first women's rights convention is held in Seneca Falls, New York. After 2 days of discussion and debate, 68 women and 32 men sign a Declaration of Sentiments, which outlines grievances and sets the agenda for the women's rights movement. A set of 12 resolutions is adopted calling for equal treatment of women and men under the law and voting rights for women. 1850 The first National Women's Rights Convention takes place in Worcester, Mass., attracting more than 1,000 participants. National conventions are held yearly (except for 1857) through 1860. 1868 Ratification of the 14th amendment declaring “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside” and that right may not be “denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens of the United States” 1870 Congress ratifies the 15th amendment: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” 1869 Split among the suffragist movement. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton form the National Woman Suffrage Association. The primary goal of the organization is to achieve voting rights for women by means of a Congressional amendment to the Constitution.