A Soldier's Play Study Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 Annual Report

Annual 2017 Report Our ongoing investment into increasing services for the senior In 2017, The Actors Fund Dear Friends, members of our creative community has resulted in 1,474 senior and helped 13,571 people in It was a challenging year in many ways for our nation, but thanks retired performing arts and entertainment professionals served in to your generous support, The Actors Fund continues, stronger 2017, and we’re likely to see that number increase in years to come. 48 states nationally. than ever. Our increased activities programming extends to Los Angeles, too. Our programs and services With the support of The Elizabeth Taylor AIDS Foundation, The Actors Whether it’s our quick and compassionate response to disasters offer social and health services, Fund started an activities program at our Palm View residence in West ANNUAL REPORT like the hurricanes and California wildfires, or new beginnings, employment and training like the openings of The Shubert Pavilion at The Actors Fund Hollywood that has helped build community and provide creative outlets for residents and our larger HIV/AIDS caseload. And the programs, emergency financial Home (see cover photo), a facility that provides world class assistance, affordable housing 2017 rehabilitative care, and The Friedman Health Center for the Hollywood Arts Collective, a new affordable housing complex and more. Performing Arts, our brand new primary care facility in the heart aimed at the performing arts community, is of Times Square, The Actors Fund continues to anticipate and in the development phase. provide for our community’s most urgent needs. Mission Our work would not be possible without an engaged Board as well as the efforts of our top notch staff and volunteers. -

West Virginia State College Lou Myers

"A century of academic excellence" West Virginia State College presents Lou Myers Artist in Residence February 15 - 19, 1991 "CentenniaL Artists Series" Lou Myers partment. In addition, he earned an M.A. in sociology from New York University. Myers made his Broadway debut in the Negro Ensemble Company's production of The First Breeze of Summer. He re- ceived the Audience Develop- ment Committee's Audelco Award for his performance in the Off-Off Broadway production of Fat Tuesday. He has also per- formed in August Wilson's Ma Rainey's Black Bottom (on Broadway) and Fences. Myers also reprised his role of "The Rev. Mosley" in the televised ver- Currently moving effortlessly sion of The First Breeze of Sum- betweenthe disparate roles of the mer, and has guest starred on The irascible "Vernon Gaines" in the Cosby Show. hit NBC-TB series A Different Myers has toured throughout World and the piano-playing the Far East and Africa and to "Winning Boy" in August more than 75 United States Col- Wilson's acclaimed play, The lege campuses with his one man Piano Lesson, Lou Myers is an cabaret act, Me and the Blues. He actor of uncommon versatility is the organizer and director of and range. the Tshaka Ensemble, which has Myers' love of performing performed Greek tragedies and began while he was growing up in Shakespearean dramas in an Af- his native Charleston, WV, where rican setting at universities and he appeared in Sunday school, performing arts centers nation- church and high school drama wide, including the Lincoln Cen- productions. -

CORT THEATER, 138-146 West 48Th Street, Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission November 17, 1987; Designation List 196 LP-1328 CORT THEATER, 138-146 West 48th Street, Manhattan. Built 1912-13; architect, Thomas Lamb . Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1000, Lot 49. On June 14 and 15, 1982, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Cort Theater and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 24). The hearing was continued to October 19, 1982. Both hearings had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Eighty witnesses spoke or had statements read into the record in favor of designation. One witness spoke in opposition to designation. The owner, with his representatives, appeared at the hearing, and indicated that he had not formulated an opinion regarding designation. The Commission has received many letters and other expressions of support in favor of this designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The Cort Theater survives today as one of the historic theaters that symbolize American theater for both New York and the nation. Built in 1912- 13, the Cort is among the oldest surviving theaters in New York. It was designed by arc hi teet Thomas Lamb to house the productions of John Cort , one of the country's major producers and theater owners. The Cort Theater represents a special aspect of the nation's theatrical history. Beyond its historical importance, it is an exceptionally handsome theater, with a facade mode l e d on the Petit Trianon in Versailles. Its triple-story, marble-faced Corinthian colonnade is very unusual among the Broadway theater s. -

LONGACRE THEATER, 220-228 West 48Th Street , Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission December 8, 1987; Designation List 197 LP-1348 LONGACRE THEATER, 220-228 West 48th Street , Manhattan. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1019, Lot 50. Built 1912-13; architect, Henry B. Herts. On June 14 and 15, 1982 , the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a pub 1 ic hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Longacre Theater and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No.44). The hearing was continued to October 19, 1982. Both hearings had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Eighty witnesses spoke or had statements read into the record in favor of designation. One witness spoke in opposition to designation. The owner, with his representatives, appeared at the hearing, and indicated that he had not formulated an opinion regarding designation. The Commission has received many letters and other expressions of support in favor of this designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The Longacre Theater survives today as one of the historic playhouses that symbolize American theater for both New York and the nation. Constructed in 1912-13, the Longacre was built to house the productions of Broadway producer and baseball magnate Harry H. Frazee . Designed for Frazee by Henry Herts, prominent theater architect, the Longacre is among the earliest surviving Broadway theaters, and has an exceptionally handsome facade. Like most Broadway playhouses built before World War I, the Longacre was designed by a leading theater architect to house the offices and theatrical productions of its owner. Though known as a baseball magnate, and at one time the owner of the Boston Red Sox, Frazee was also an influential Broadway producer who, besides building the Longacre theater, at one time also owned two other Broadway houses (the Harris and the Lyric). -

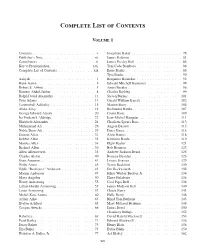

Complete List of Contents

Complete List of Contents Volume 1 Contents. v Josephine Baker . 78 Publisher’s Note . vii James Baldwin. 81 Contributors . xi James Presley Ball. 84 Key to Pronunciation. xvii Toni Cade Bambara . 86 Complete List of Contents . xix Ernie Banks . 88 Tyra Banks. 90 Aaliyah . 1 Benjamin Banneker . 92 Hank Aaron . 3 Edward Mitchell Bannister . 94 Robert S. Abbott . 5 Amiri Baraka . 96 Kareem Abdul-Jabbar . 8 Charles Barkley . 99 Ralph David Abernathy . 11 Steven Barnes . 101 Faye Adams . 14 Gerald William Barrax . 102 Cannonball Adderley . 15 Marion Barry . 104 Alvin Ailey . 18 Richmond Barthé. 107 George Edward Alcorn . 20 Count Basie . 109 Ira Frederick Aldridge. 22 Jean-Michel Basquiat . 111 Elizabeth Alexander . 24 Charlotta Spears Bass . 113 Muhammad Ali . 26 Angela Bassett . 115 Noble Drew Ali . 29 Daisy Bates. 116 Damon Allen . 31 Alvin Batiste . 118 Debbie Allen . 33 Kathleen Battle. 119 Marcus Allen . 34 Elgin Baylor . 121 Richard Allen . 36 Bob Beamon . 123 Allen Allensworth . 38 Andrew Jackson Beard. 125 Charles Alston . 40 Romare Bearden . 126 Gene Ammons. 41 Louise Beavers . 129 Wally Amos . 43 Tyson Beckford . 130 Eddie “Rochester” Anderson . 45 Jim Beckwourth . 132 Marian Anderson . 47 Julius Wesley Becton, Jr. 134 Maya Angelou . 50 Harry Belafonte . 136 Henry Armstrong . 53 Cool Papa Bell . 138 Lillian Hardin Armstrong . 55 James Madison Bell . 140 Louis Armstrong . 57 Chuck Berry . 141 Molefi Kete Asante . 60 Halle Berry . 144 Arthur Ashe . 63 Blind Tom Bethune . 145 Evelyn Ashford . 65 Mary McLeod Bethune . 148 Crispus Attucks . 66 James Bevel . 150 Chauncey Billups . 152 Babyface. 69 David Harold Blackwell . 153 Pearl Bailey . 71 Edward Blackwell . -

An Interview with Elaine Jackson

The Journal of American Drama and Theatre (JADT) https://jadtjournal.org An Interview with Elaine Jackson by Nathaniel G. Nesmith The Journal of American Drama and Theatre Volume 33, Number 2 (Spring 2021) ISNN 2376-4236 ©2021 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center Elaine Jackson, born in Detroit (1938), began her career in the theatre as an actress. In the early 1970s, she established her career as a playwright with her first produced play, Toe Jam (1971). She went forward to write some of the most provocative dramas of the 1970s and 1980s, always offering a celebratory vision of women and their advancements. Her most well-known plays are Cockfight (1976), Paper Dolls (1979), Birth Rites (1987), and Puberty Rites (2011). She has received several notable awards and honors, including the Rockefeller Award for Playwriting for 1978–1979; the Langston Hughes Playwriting Award (1979); and the National Endowment for the Arts Award for playwriting (1983). In addition to serving as Playwright in Residence at Lake Forest College (1990) and at Wayne State University (1991), where she earned her undergraduate degree, Ms. Jackson is an educator who has taught at various institutions. I had an opportunity to sit down with Ms. Jackson to discuss her career and her continued efforts in the theatre. The initial interview took place during the spring of 2019, and we continued our conversation via telephone through the summer of 2020. Nathaniel G. Nesmith: I read that you have been involved in theatre since you were ten. Could you contextualize your early theatre involvement? Elaine Jackson: At the age of ten, I was in elementary school and that was my first adventure on the stage. -

Portraying the Soul of a People: African Americans Confront Wilson’S Legacy from the Washington Stage

Portraying the Soul of a People: African Americans Confront Wilson’s Legacy From the Washington Stage BLAIR A. RUBLE CONTENTS African Americans Confront Wilson’s Legacy 3 From the Washington Stage 6 From Mask to Mirror The Washington 8 Antilynching Plays A Child of Howard 10 University Returns Confronting Racist 12 Stage Traditions 14 Singing Our Song From Drama Club to 17 Theater Company A Theater Born at 20 Howard A University-based Strategy for a 23 New Theater Universities over 24 Commerce 27 Playing before the World 30 The Emperor Jones 34 University Drama 38 The New Negro 41 Board Intrigues Campus and 45 Community Plays of Domestic 50 Life 53 Saturday Night Salons Changing of the 55 Guard A Scandinavian Prince of Another 59 Hue 64 Curtain Call 65 About the Author 66 Acknowledgements 68 Notes Still there is another kind of play: the play that shows the soul of a people; and the soul of this people is truly worth showing. —Willis Richardson, 19191 2 PORTRAYING THE SOUL OF A PEOPLE Portraying the Soul of a People: African Americans Confront Wilson’s Legacy From the Washington Stage BLAIR A. RUBLE | Distinguished Fellow n 1903, a twenty-year-old journalist who would go on to a distinguished career in journalism, diplomacy, and politics—future US minister to Liberia, Lester Aglar Walton—excitedly told the readers of The Colored I 2 American Magazine of African American successes on stage. “The outlook for the Negro on the stage is particularly bright and encouraging,” Walton began. “At no time have colored stage folk been accorded such consideration and loyal support from show managers, the press and the general public… Heretofore, colored shows have only found their way to New York theatres of minor importance; and the crowded houses invariable in evidence where ‘coon’ shows have played have been occasioned more by reason of the meritorious work of the performers than by the popularity of the playhouses.” To Walton’s mind, “catchy music, mirth-provoking dialogue and mannerisms void of serious lines” had ensured the success of recently produced “coon”shows.