JE,Itia {)Izabeth ~Ndon (1802-1838)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issues) and Begin with the Summer Issue

VOLUME 22 NUMBER 3 WINTER 1988/89 ■iiB ii ••▼•• w BLAKE/AN ILLUSTRATED QUARTERLY WINTER 1988/89 REVIEWS 103 William Blake, An Island in the Moon: A Facsimile of the Manuscript Introduced, Transcribed, and Annotated by Michael Phillips, reviewed by G. E. Bentley, Jr. 105 David Bindman, ed., William Blake's Illustrations to the Book of Job, and Colour Versions of William- Blake 's Book of job Designs from the Circle of John Linnell, reviewed by Martin Butlin AN ILLUSTRATED QUARTERLY VOLUME 22 NUMBER 3 WINTER 1988/89 DISCUSSION 110 An Island in the Moon CONTENTS Michael Phillips 80 Canterbury Revisited: The Blake-Cromek Controversy by Aileen Ward CONTRIBUTORS 93 The Shifting Characterization of Tharmas and Enion in Pages 3-7 of Blake's Vala or The FourZoas G. E. BENTLEY, JR., University of Toronto, will be at by John B. Pierce the Department of English, University of Hyderabad, India, through November 1988, and at the National Li• brary of Australia, Canberra, from January-April 1989. Blake Books Supplement is forthcoming. MARTIN BUTLIN is Keeper of the Historic British Col• lection at the Tate Gallery in London and author of The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake (Yale, 1981). MICHAEL PHILLIPS teaches English literature at Edinburgh University. A monograph on the creation in J rrfHRurtfr** fW^F *rWr i*# manuscript and "Illuminated Printing" of the Songs of Innocence and Songs ofExperience is to be published in 1989 by the College de France. JOHN B. PIERCE, Assistant Professor in English at the University of Toronto, is currently at work on the manu• script of The Four Zoas. -

How the Tomb Becomes a Womb by Eric Howell

© 2013 Center for Christian Ethics at Baylor University 11 How the Tomb Becomes a Womb BY ERIC HOWELL By baptism “you died and were born,” a fourth-century catechism teaches. “The saving water was your tomb and at the same time a womb.” When we are born to new life in those ‘maternal waters,’ we celebrate and receive grace that shapes how we live and die. ollowing an extended argument in which the grace given to us through Christ is set over against the sinful nature we inherit from Adam, the FApostle Paul asks: “What shall we say then?” (Romans 6:1, ESV)1 and the implied answer is clear: grace wins. This is especially clear in the crescendo of his argument: “but where sin increased, grace abounded all the more, so that, as sin reigned in death, grace also might reign through righteousness leading to eternal life through Jesus Christ our Lord” (5:20b-21, ESV). Immediately Paul recognizes that his argument sets a dangerous theological trap to be sprung. He must now disarm the derivation from his premise of a devious conclusion: namely, since more sin equals more grace, therefore, sin more! Before the trap can be sprung, Paul spins on the point and asks, “What shall we say then? Are we to continue in sin that grace may abound?” (6:1, ESV) No way! How can we who died to sin still live in it? For Paul, the gift of God’s grace is an invitation to a new way of life, a radical discipleship to Jesus Christ that puts to death the old life and gives birth to new life. -

A Manuscript Poem by Letitia Elizabeth Landon ("L.E.L.")

Connotations Vol. 3.2 (1993/94) Christmas as Humbug: A Manuscript Poem by Letitia Elizabeth Landon ("L.E.L.") F. J. SYPHER "L.E.L." -as she signed her work-enjoyed great popularity and esteem during the 1820s and 1830s, not only in England, but also in the United States and on the European Continent.1 Landon was a literary prodigy, who started to compose poems as a child and began publishing in March 1820, when she was seventeen years old. She died at the age of thirty-six, in West Africa, where she had gone to live after her marriage in June 1838 to George Maclean, governor of the British post at Cape Coast (in present-day Ghana). In her remarkably productive career, Landon wrote seventeen volumes of poetry, three substantial novels, two books of short stories, a tragedy, countless reviews and critical articles, and many other works, in addition to journals and letters. In fact, considering the quantity and variety of her work, and the high regard accorded it by contempora- ries, one might make a case for Landon as one of the most prominent English poets during the period between the death of Byron in 1824 and the emergence of the great Victorians. Among specific reasons why her poetry is not better known today, is perhaps her early predilection for the now-obsolete genre of romantic verse narrative as, for instance, in The Improvisatrice (1824), or The Troubadour (1825), which were inspired by Sir WaIter Scott's poems. Furthermore, many of Landon's poems appeared in annual volumes like Forget Me Not, The Keepsake, or Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book-gift-books which enjoyed a great vogue at the time but went out of fashion in the 1840s, when Landon's work went out too, as if by association with an outmoded cultural phenomenon. -

Blake's Critique of Enlightenment Reason in the Four Zoas

Colby Quarterly Volume 19 Issue 4 December Article 3 December 1983 Blake's Critique of Enlightenment Reason in The Four Zoas Michael Ackland Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 19, no.4, December 1983, p.173-189 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Ackland: Blake's Critique of Enlightenment Reason in The Four Zoas Blake's Critique of Enlightenment Reason in The Four Zoas by MICHAEL ACKLAND RIZEN is at once one of Blake's most easily recognizable characters U and one of his most elusive. Pictured often as a grey, stern, hover ing eminence, his wide-outspread arms suggest oppression, stultifica tion, and limitation. He is the cruel, jealous patriarch of this world, the Nobodaddy-boogey man-god evoked to quieten the child, to still the rabble, to repress the questing intellect. At other times in Blake's evolv ing mythology he is an inferior demiurge, responsible for this botched and fallen creation. In political terms, he can project the repressive, warmongering spirit of Pitt's England, or the collective forces of social tyranny. More fundamentally, he is a personal attribute: nobody's daddy because everyone creates him. As one possible derivation of his name suggests, he is "your horizon," or those impulses in each of us which, through their falsely assumed authority, limit all man's other capabilities. Yet Urizen can, at times, earn our grudging admiration. -

New Risen from the Grave: Nineteen Unknown Watercolors by William Blake

ARTICLE New Risen from the Grave: Nineteen Unknown Watercolors by William Blake Martin Butlin Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 35, Issue 3, Winter 2002, pp. 68-73 Cromek. Suffice it to say that John Flaxman, in a letter of 18 ARTICLES October 1805, wrote that "Mr. Cromak has employed Blake to make a set of 40 drawings from Blair's poem of the Grave New Risen from the Grave: 20 of which he proposes [to] have engraved by the Designer ..." (Bentley (2001) 279). Blake himself, in a letter to Will- Nineteen Unknown Watercolors iam Hayley of 27 November 1805, wrote that about two by William Blake months earlier "my Friend Cromek" had come "to me de- siring to have some of my Designs, he namd his Price & wishd me to Produce him Illustrations to The Grave A Poem BY MARTIN BUTLIN by Robert Blair, in consequence of this I produced about twenty Designs which pleasd so well that he with the same hat is certainly the most exciting Blake discovery since liberality with which he set me about the Drawings, has now WI began work on the artist, and arguably the most set me to Engrave them."2 Cromek, in the first version of important since Blake began to be appreciated in the sec- his Prospectus, dated November 1805, advertised "A NEW AND ond half of the nineteenth century, started in a deceptively ELEGANT EDITION OF BLAIR'S GRAVE, ILLUSTRATED WITH FIFTEEN low-key way. A finished watercolor for the engraving of "The PRINTS FROM DESIGNS INVENTED AND TO BE ENGAVED BY WILLIAM Soul Hovering over the Body," published in Robert Cromek's BLAKE .. -

COLLECTION NAME: Landon (Letitia) Collection. DETAILED CONTENTS: SECTION A. TEXTS. A:1. "The Legacy of the Lute." [Poe

MS COLLECTION NAME: Landon (Letitia) collection. 223 Page 3 DETAILED CONTENTS: SECTION A. TEXTS. • A:1. "The Legacy of the Lute." [poec --draft] 4 pieces. p. 1: "The <Legacy of the> Lute. Come take the lute-- the lute I touch ••• " p. 2: "The Minstrel lute! oh, touch it not •.• " p. 3: "Away upon the autumn wind; • • • \-/hose only music was thy nan:e. L.E.L." p. 3[b]: "The shades of past delight Fling down the wreath, and break the lute They mock our souls tonight. L.E.L". [This scrap is tipped onto the foot of p. 3, and is also marked 3.] p. 3 docketed: "L.E.L. -- Poetry. ~~g WJ Early proof" A:2. The Sailor. [poem -- late draft] 2 pieces. p. [1]: "The Sailor~e-LePe [?]. He was their last and their only child ••• p. [2]: "That night it was a servant's hand ••• And the wan waves were breaking. L.E.L." Originally written on a long "galley-proof" slip (20.5 x 4.5"); then cut into 2 pieces ca 10" high. p. 2 docketed: "The Sailor's [illegible]" Published as "The Sailor" in Friendship's Offering 25:238, ace. to Boyle. A:3. [The Altered River.] [poe~-- fair copy.] 1 p., in two columns. {1 piece) "Thou lovely river, thou ar't now .•. and when have dreams not flown. L.E.L." • Marked in pencil "310" and "3[4?]3". Published as "The Altered River" in Keepsake 29:310, ace. to Eoyle. A:4. "Farewell." [poem-- gift copy.] 1 p. and docketing. -

Empire and Melancholy in Romantic India

“Doleful Records”: Empire and Melancholy in Romantic India by Tara McDonald A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English University of Toronto © Copyright by Tara McDonald (2015) “Doleful Records”: Empire and Melancholy in Romantic India Tara McDonald Doctor of Philosophy Department of English University of Toronto 2015 Abstract This dissertation considers how the feelings unleashed by death – namely mourning and melancholy – were harnessed to understand, organize, and legitimate imperial power in India during the British Romantic period. The project examines the writing of women authors such as Mariana Starke, Phebe Gibbes, Elizabeth Hamilton, Letitia Elizabeth Landon, Felicia Hemans, Sydney Owenson, and Emma Roberts alongside contemporary political debates to demonstrate how the affective strategies surrounding death were performing the labour of empire in the literary topography and psychogeography of the late eighteenth to mid-nineteenth centuries. Faced with personal, political, and national losses on a grand scale, Britons had to reimagine grief as a force to be mobilized and deployed, rather than one acting upon them. The difficulty of dealing with death from the distance and difference of a foreign outpost, where the traditional networks of consolation could not be accessed, demanded new forms of sympathy, sociability, and a reconstitution of communal identity in response to losses that could not be confronted. While the bodies of the dead grounded the imperial project in India, the mobility of their printed afterlives reconnected them to a sympathetic national body at home. The first chapter of this dissertation demonstrates how Elizabeth Hamilton exploits melancholy as ii a rhetorical strategy that provides women with access to political discourse and posits mourning as an affective branch of the imperial project. -

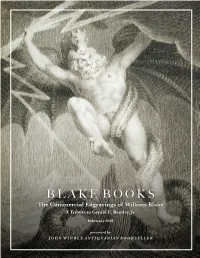

Blake Books, Contributed Immeasurably to the Understanding and Appreciation of the Enormous Range of Blake’S Works

B L A K E B O O K S The Commercial Engravings of William Blake A Tribute to Gerald E. Bentley, Jr. February 2018 presented by J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R T H E W I L L I A M B L A K E G A L L E R Y B L A K E B O O K S The Commercial Engravings of William Blake A Tribute to Gerald E. Bentley, Jr. February 2018 Blake is best known today for his independent vision and experimental methods, yet he made his living as a commercial illustrator. This exhibition shines a light on those commissioned illustrations and the surprising range of books in which they appeared. In them we see his extraordinary versatility as an artist but also flashes of his visionary self—flashes not always appreciated by his publishers. On display are the books themselves, objects that are far less familiar to his admirers today, but that have much to say about Blake the artist. The exhibition is a small tribute to Gerald E. Bentley, Jr. (1930 – 2017), whose scholarship, including the monumental bibliography, Blake Books, contributed immeasurably to the understanding and appreciation of the enormous range of Blake’s works. J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R 49 Geary Street, Suite 205, San Francisco, CA 94108 www.williamblakegallery.com www.johnwindle.com 415-986-5826 - 2 - B L A K E B O O K S : C O M M E R C I A L I L L U S T R A T I O N Allen, Charles. -

The Book of Copper and the Anvil of Death: Gothic Elements of William Blake’S Creation Myth

6/17/2019 Blake Thesis, Final Draft - Google Docs Joint Master’s Degree in European, American and Postcolonial Language and Literature Ca’ Foscari University of Venice Final Thesis The Book of Copper and the Anvil of Death: Gothic Elements of William Blake’s Creation Myth Supervisor Professor Michela Vanon Alliata Student Claire Burgess 864825 Academic Year 2018/2019 https://docs.google.com/document/d/19-a1eJAqtzUA1vtbP9u6Uy6glwF_BLZCVKku-noOLHo/edit 1/90 6/17/2019 Blake Thesis, Final Draft - Google Docs 1 Table of Contents Preludium………………….…………………….…………………….….………….….…….2 I: The Seeker After Forbidden Knowledge………………….……….………….………….14 II: The Divine Gift of Language …………………….………….…………………..….…….19 III: The World as Holy Book ………………….………………….……....…………….…….23 IV: Polysemous Language …………………….…………………...…….…………..……….27 V: The Grave as the Source of Knowledge……………………...……………….….………32 VI: The Grave as Realm of Disorientation………………….…………..……..……….……37 VII: Marrying the Sister Arts in Illuminated Printing……………….…….………………43 VIII: The Word as Graven Image………………….………………….…….……………….48 IX: Prosedy & Song………………….………………….……………....…….………………51 X: Oral Storytelling………………….………………….……………..……….………….….58 XI: The Narrative Contract………………….………………….……………….……..….…60 XII: Riddles, Charms, & Magic………………….………………….………………..……….62 XIII: The Three Fates………………….………………….…………………....….…………66 XIV: Monstrous Men………………….………………….………....…………..…………….70 Finis …………………….…………………….………………..……….…….……………….79 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………....84 https://docs.google.com/document/d/19-a1eJAqtzUA1vtbP9u6Uy6glwF_BLZCVKku-noOLHo/edit -

Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century British Women Writers University Libraries--University of South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Irvin Department of Rare Books & Special Rare Books & Special Collections Publications Collections 3-1996 Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century British Women Writers University Libraries--University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/rbsc_pubs Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation University of South Carolina, "University of South Carolina Libraries - Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century British Women Writers, March 1996". http://scholarcommons.sc.edu/rbsc_pubs/22/ This Catalog is brought to you by the Irvin Department of Rare Books & Special Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Rare Books & Special Collections Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Eighteenth & Nineteenth Century BRiTISH WOMEN WRITERS Mezzanine Exhibit Area Thomas Cooper Library University oESouth Carolina This special exhibition, selected from the University's Department of Special Collections, marks the occasion of the fifth Conference on Eighteenth & Nineteenth Century British Women Writers, to be held in Columbia on March 21st-24th 1996. The exhibition covers a full chronological spectrum, from Margaret Cavendish's Poems and phancies, 1664, and Ann Finch's "The Spleen" in its first edition of 1701 to an inscribed volume by 'Violet Fane' from 1896, where she descibes herself semi-ironically as "an obscure poet." Many of the "collector's high points" of literature by women are displayed, including first editions of WoUstonecraft's Vindication, Shelley's Frankenstein, Emily Bronte's Wuthering Heights, and Rossetti's Goblin Market, as well as first editions by Austen, Charlotte and Ann Bronte, George Eliot and other well-known names. -

William Blake in Context Edited by Sarah Haggarty Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-14491-0 — William Blake in Context Edited by Sarah Haggarty Frontmatter More Information WILLIAM BLAKE IN CONTEXT William Blake, poet and artist, is a figure often understood to have ‘created his own system’. Combining close readings and detailed analysis of a range of Blake’s work, from lyrical songs to later myth, from writing to visual art, this collection of thirty-eight lively and authoritative essays examines what Blake had in common with his contemporaries, the writers who influenced him, and those he influ- enced in turn. Chapters from an international team of leading scho- lars also attend to his wider contexts: material, formal, cultural, and historical, to enrich our understanding of, and engagement with, Blake’s work. Accessibly written, incisive, and informed by original research, William Blake in Context enables readers to appreciate Blake anew, from both within and outside of his own idiom. sarah haggarty is Lecturer in the Faculty of English and Fellow of Queens’ College, at the University of Cambridge. She has published three previous books about Blake: Blake’s Gifts: Poetry and the Politics of Exchange (Cambridge, 2010); William Blake: Songs of Innocence and of Experience (1794) (with Jon Mee, 2013); and Blake and Conflict (with Jon Mee, 2009). © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-14491-0 — William Blake in Context Edited by Sarah Haggarty Frontmatter More Information © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org -

THE UNIVERSITY of HULL Four Literary Protegees of the Lake

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL Four Literary Protegees of the Lake Poets: Caroline Bowles, Maria Gowen Brooks, Sara Coleridge and Maria Jane Jewsbury being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Hull by Dennis Jun-Yu Low, SA (Oxon) March 2003 Therefore, although it be a history Homely and rude, I will relate the same For the delight of a few natural hearts: And, with yet fonder feeling, for the sake Of youthful Poets, who among these hills Will be my second self when I am gone. Wordsworth Contents Contents ......................................................................................................................................... 1 Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................ 2 List of Abbreviations ....................................................................................................................... 4 Preface ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Chapter 1: The Lake Poets and 'The Era of Accomplished Women' ............................................ 13 Chapter 2: Caroline Bowles .......................................................................................................... 51 Chapter 3: Maria Gowen Brooks ................................................................................................ 100 Chapter 4: Sara Coleridge .........................................................................................................