Mobile Call Termination Market Review 2018-2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Code Compliance Panel Tribunal Decision

Code Compliance Panel Tribunal Decision Tribunal meeting number 185 / Case 1 Case reference: 72402 Level 2 provider: VisionSMS Ltd (UK) Type of service: “Ursexybabes.com” glamour video subscription service Level 1 provider: Veoo Ltd (UK); IMImobile Europe Limited (UK); Fonix Mobile Ltd (UK) Network operator: All Mobile Network operators THIS CASE WAS BROUGHT AGAINST THE LEVEL 2 PROVIDER UNDER PARAGRAPH 4.4 OF THE CODE BACKGROUND The case concerned a glamour video subscription service, charged at £3 per week, under the brand name “Ursexybabes.com”, operating on dedicated shortcodes 69119, 85085 and 89880 (the “Service”). The Level 2 provider for the Service was VisionSMS Ltd (the “Level 2 provider”). The Level 2 provider had been registered with PhonepayPlus since 17 August 2011. The Level 1 provider for Service shortcode 69119 was IMImobile Europe Limited (“IMImobile”). The Level 1 provider for Service shortcode 85085 was Fonix Mobile Limited (“Fonix”). The Level 1 provider for Service shortcodes 89880 was Veoo Ltd (“Veoo”). The Service The Service was stated to be a glamour video subscription service charged at £3 per week. The Level 2 provider confirmed that the Service commenced operation in October 2011, and remained operational as at 11 May 2016. IMImobile stated the Service commenced operation on shortcode 69119 in June 2010. Fonix stated that the Service commenced operation on shortcode 85085 on 28 June 2014. Veoo stated that the Service commenced operation on shortcode 89880 on 24 October 2014. The table below sets out the shortcodes on which the Service(s) operated and the Level 1 providers for each shortcode: Service name Shortcode Level 1 provider Cost per week ‘ursexybabes.com’ 69119 IMImobile Europe £3 Limited 85085 Fonix Mobile Limited 89880 Veoo Ltd The Level 2 provider supplied the following summary of the promotion of the Service: Code Compliance Panel Tribunal Decision “We advertise our service online using banner adverts which link to our site containing videos. -

Fonix Mobile Plc (Incorporated Under the Companies Act 2006 and Registered in England and Wales with Registered Number 05836806)

THIS DOCUMENT IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION. If you are in any doubt about the contents of this document or as to the action you should take, you are recommended to seek your own personal financial advice immediately from your stockbroker, bank manager, solicitor, accountant or other independent financial adviser authorised under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (as amended), who specialises in advising on the acquisition of shares and other securities if you are resident in the UK or, if not, from another appropriately authorised independent adviser. This document, which comprises an AIM admission document prepared in accordance with the AIM Rules for Companies, has been issued in connection with the application for admission of the entire issued ordinary share capital of the Company to trading on AIM. This document contains no offer of transferable securities to the public within the meaning of sections 85 and 102B of the FSMA, the Act or otherwise. Accordingly, this document does not constitute a prospectus within the meaning of section 85 of the FSMA and has not been drawn up in accordance with the Prospectus Regulation Rules or approved by, or filed with, the FCA or any other competent authority. Application has been made for the ordinary share capital of the Company to be admitted to trading on AIM. No application has been, or is currently intended to be, made for the Ordinary Shares to be admitted to listing or trading on any other stock exchange. It is expected that Admission will become effective and that dealings will commence in the Ordinary Shares on 12 October 2020. -

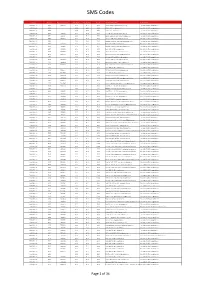

Vas Shortcode Pricing

SMS Codes Company Shortcode Shortcode reply number Pay Monthly Pay As you Go Reply cost End user contact details Esclation details Fonix Mobile Ltd 60016 700032653 £0.10 £0.12 £1.00 Isomob, 08000356780, [email protected] Fonix, 0208 114 7001, [email protected] Fonix Mobile Ltd 60019 £0.00 £0.00 £0.00 0208 1147001, [email protected] Fonix, 0208 114 7001, [email protected] Fonix Mobile Ltd 60020 £0.00 £0.00 £0.00 0208 1147001, [email protected] Fonix, 0208 114 7001, [email protected] Fonix Mobile Ltd 60039 700026651 £0.10 £0.12 £0.50 1st 4 PRS, 0161 956 3505, [email protected] Fonix, 0208 114 7001, [email protected] Fonix Mobile Ltd 60061 700046144 £0.10 £0.12 £4.50 Braniq Products B.V, 0203 734 9251, [email protected] Fonix, 0208 114 7001, [email protected] Fonix Mobile Ltd 60082 700010229 £0.10 £0.12 £0.10 Infomedia, 0800 1512392, [email protected] Fonix, 0208 114 7001, [email protected] Fonix Mobile Ltd 60088 £0.00 £0.00 £0.00 Messagebird, 0208 114 7001, [email protected] Fonix, 0208 114 7001, [email protected] Fonix Mobile Ltd 60096 700046066 £0.10 £0.12 £4.50 Fonix, 0208 114 7001, [email protected] Fonix, 0208 114 7001, [email protected] Fonix Mobile Ltd 60180 700010367 £0.10 £0.12 £0.12 Messagebird, 0800 0776990, [email protected] Fonix, 0208 114 7001, [email protected] Fonix Mobile Ltd 60201 700010386 £0.10 £0.12 £0.10 Fonix, 0208 114 7001, [email protected] Fonix, 0208 114 7001, [email protected] Fonix Mobile Ltd 60345 700035632 £0.10 £0.12 £1.50 Cellcast, 0333 335 0298, [email protected] Fonix, 0208 114 7001, [email protected] Fonix Mobile Ltd 60445 700046123 £0.10 -

20190201VAS Pricing.Xlsx

SMS Codes Company Shortcode Shortcode reply number Pay Monthly Pay As you Go Reply cost End user contact details Esclation details Fonix Mobile Ltd 60016 700032653 £0.10 £0.12 £1.00 Isomob, 08000356780, [email protected] Fonix, 0208 114 7001, [email protected] Fonix Mobile Ltd 60019 £0.00 £0.00 £0.00 0208 1147001, [email protected] Fonix, 0208 114 7001, [email protected] Fonix Mobile Ltd 60020 £0.00 £0.00 £0.00 0208 1147001, [email protected] Fonix, 0208 114 7001, [email protected] Fonix Mobile Ltd 60039 700026651 £0.10 £0.12 £0.50 1st 4 PRS, 0161 956 3505, [email protected] Fonix, 0208 114 7001, [email protected] Fonix Mobile Ltd 60061 700046144 £0.10 £0.12 £4.50 Braniq Products B.V, 0203 734 9251, [email protected] Fonix, 0208 114 7001, [email protected] Fonix Mobile Ltd 60082 700010229 £0.10 £0.12 £0.10 Infomedia, 0800 1512392, [email protected] Fonix, 0208 114 7001, [email protected] Fonix Mobile Ltd 60088 £0.00 £0.00 £0.00 Messagebird, 0208 114 7001, [email protected] Fonix, 0208 114 7001, [email protected] Fonix Mobile Ltd 60096 700046066 £0.10 £0.12 £4.50 Fonix, 0208 114 7001, [email protected] Fonix, 0208 114 7001, [email protected] Fonix Mobile Ltd 60180 700010367 £0.12 £0.12 £0.12 Messagebird, 0800 0776990, [email protected] Fonix, 0208 114 7001, [email protected] Fonix Mobile Ltd 60201 700010386 £0.10 £0.12 £0.10 Fonix, 0208 114 7001, [email protected] Fonix, 0208 114 7001, [email protected] Fonix Mobile Ltd 60345 700035632 £0.10 £0.12 £1.50 Cellcast, 0333 335 0298, [email protected] Fonix, 0208 114 7001, [email protected] Fonix Mobile Ltd 60445 700046123 £0.10 -

In This Issue

monetizing connected consumers ISSUE 57 | £4.99 IPRN weathers the storm Messaging mad Mobility 14 International Premium Rate Messaging is Using mobile to Services (IPRN) are on the starting to become travel – what up as new markets look for a monetisable could be more ways to pay for content and delivery channel. mobile. As the apps – despite coronavirus Take a look at how world opens up find hitting call centres it is developing out how it works IN THIS ISSUE 16 20 TELECOMS & NETWORK PROVIDERS IN THIS ISSUE Voice and IPRN 06 GAMING: LET US PLAY The world has gone content crazy traffic: how during lockdown and games lead the coronavirus has way. What are the opportunities? 08 AFFILIATES DRIVE RETAIL shifted telecoms More peopel than ever are shopping on line and on mobile – and this is proving to be aboon to affilaites 10 PAYMENTS BOOM Payments are top of the agenda across ecomemrce and mobile content - we take a look at who is winning 10 GAMBLING GOES GLOBAL With our white paper on DCB for The coronavirus pandemic and the CONTENT gambling going live, we assess how attendant lockdown around the world Content services – particularly games, gam- gambling has exploded in 2020 has had a profound impact on telemedia bling, eSports and chat services – have all markets: content services and the billing had a huge boost over the lockdown, with a 22 FRAUD IN A TIME OF CRISIS that goes with it have rocketed, while a study by Bango into what people in coun- We take an in depth look at how the voice traffic has gone up. -

Mobile Call Termination Market Review 2015-18 Draft Decision

Mobile call termination market review 2015-18 Draft decision Draft Statement Date of notification to EC: 6 February 2015 MCT Review 2015-18 About this document This document sets out in draft the conclusion of our review of the wholesale ‘mobile call termination’ (MCT) markets for the period 1 April 2015 – 31 March 2018. MCT is a wholesale service provided by a mobile communications provider (MCP) to connect a call to a recipient on its network. When fixed or mobile communications providers enable their customers to call a UK mobile number, they pay the terminating MCP a wholesale charge, called a ‘mobile termination rate’ (MTR). MTRs are set on a per-minute basis and are currently subject to regulation. We published a consultation document on 4 June 2014 outlining our regulatory proposals for MCT markets. We have taken account of points raised by stakeholders and new information received since the consultation. In this document we set out our decisions, including the regulation that we conclude is appropriate for this market. The regulation we have decided to impose includes a charge control on the MTRs of all MCPs offering MCT and is designed to promote competition and further the interests of consumers. This draft statement is today being notified to the European Commission. Once this notification process is complete, we will publish a final statement to bring our decisions into effect. MCT Review 2015-18 Contents Section Page 1 Summary 1 2 Introduction and background 4 3 Product and geographic market definition 21 4 SMP assessment 52 5 Remedies 64 6 Cost standard for the MTR charge control 92 7 Calculating the efficient costs of MCT 141 8 Implementation of the charge control 150 MCT Review 2015-18 Section 1 1 Summary 1.1 This draft statement sets out the conclusions of our review of the wholesale ‘mobile call termination’ (MCT) markets for the period 1 April 2015 – 31 March 2018.