Internal Migration and Regional Population Dynamics in Estonia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Working Together for Better Health and Well-Being for All Fifth High-Level Meeting of Small Countries Reykjavik, Iceland, 26–27 June 2018

Working Together for Better Health and Well-being for All Fifth High-level Meeting of Small Countries Reykjavik, Iceland, 26–27 June 2018 Working Together for Better Health and Well-being for All Fifth High-level Meeting of Small Countries Reykjavik, Iceland, 26–27 June 2018 Abstract The Small Countries Initiative was established in 2013, and has developed into a platform through which the eight Member States in the WHO European Region with populations of less than 1 million – Andorra, Cyprus, Iceland, Luxembourg, Malta, Monaco, Montenegro and San Marino – share their experiences in implementing Health 2020, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its Sustainable Development Goals and the WHO European roadmap to implement the 2030 Agenda. Members meet yearly to take stock of their progress, experience and challenges in improving population health and reducing health inequities. Fully resonating with the very essence of both Health 2020 and the 2030 Agenda, the Fifth High-level Meeting of the Small Countries, with the theme of working together for better health and well-being for all, addressed a technical agenda informed by the latest European and global events, positioning the Initiative as a unique, forward-thinking platform. Keywords Healthy People Programs Health Plan Implementation Health Policy International Cooperation Conservation of Natural Resources Europe Address requests about publications of the WHO Regional Office for Europe to: Publications WHO Regional Office for Europe UN City, Marmorvej 51 DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark Alternatively, complete an online request form for documentation, health information, or for permission to quote or translate, on the Regional Office web site (http://www.euro.who.int/ pubrequest). -

LIST of CONTACTS / LISTE DES CONTACTS (Up-Dated on / Mise À Jour Le : 20 September 2017 / 20 Septembre 2017) COUNCIL of EUROPE

LIST OF CONTACTS / LISTE DES CONTACTS (up-dated on / mise à jour le : 20 September 2017 / 20 septembre 2017) COUNCIL OF EUROPE / CONSEIL DE L’EUROPE Directorate of Democratic Citizenship and Participation/Direction de la Citoyenneté Démocratique et de la Participation Division for co-operation and capacity building/Division de la coopération et du renforcement des capacités Pestalozzi Programme, Training Programme for education professionals Programme Pestalozzi, Programme de formation pour les professionnels de l’éducation Direction Générale II, Conseil de l'Europe, 67075 STRASBOURG CEDEX Mr Josef HUBER Head of Unit / Chef de l’Unité E-mail: [email protected] Language/Langues : English + Français + Deutsch Ms Isabelle LACOUR Assistant for the management of the Pestalozzi Programme Assistante à la gestion du programme Pestalozzi E-mail: [email protected] Language/Langues : Français + English + Deutsch + Elsässisch Mr Didier FAUCHEZ Assistant for the social networking platform and for the web site of the Pestalozzi Programme Assistant plate-forme du réseau social et pour le site web du Programme Pestalozzi E-mail: [email protected] Language/Langues: Français + English Ms Bogdana BUZARNESCU Assistant for the Pestalozzi Programme E-mail: [email protected] Language/Langues : English + Français +Română + Español Ms Tara HULLEY Assistant for the Pestalozzi Programme E-mail: [email protected] Language/Langues : English + Français Ms Manola GAVAZZI Seconded by the Italian Authorities to the Pestalozzi Programme (October -

List of Participants 7Th Meeting of the Task Force on Access to Information Under the Aarhus Convention

Task Force on Access to Information under the Aarhus Convention List of participants 7th meeting of the Task Force on Access to Information under the Aarhus Convention Start Date: Monday, November 16, 2020 End Date: Tuesday, November 17, 2020 Chair H.E. Ms. Tatiana MOLCEAN Geneva Switzerland Ambassador Permanent Mission of the Republic of Moldova to the United Nations Office in Geneva Governments (UNECE Bodies) - ECE Member States Albania Ms. Edlira DERSHA Tirane Albania Public Relation Officer Email: edlira.dersha[at]turizmi.gov.al Ministry of Tourism and Environment Austria Mr. Florian WOLF-OTT Vienna Austria Desk officer Email: florian.ott[at]umweltbundesamt.at Environment Agency Austria Ms. Renate MUELLNER-SPARBER Vienna Austria Member Email: renate.muellner- Federal Ministry of Climate Affairs sparber[at]bmk.gv.at Belarus Ms. Alena MELIASHKOVA Minsk Belarus Deputy Head of the Department of Email: alen-me[at]yandex.ru Analytical Work, Science and Information Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Task Force on Access to Information under the Aarhus Convention Ms. Galina MOZGOVA Minsk Belarus Head of the National Co-ordination Biosafety Centre Email: g.mozgova[at]yandex.ru Institute of Genetics and Cytology of the National Academy of Sciences of Belarus Ms. Volha ZAKHARAVA Minsk Belarus Manager Email: aarhus.by[at]gmail.com Aarhus centre Cyprus Ms. Valentina MICHAEL Nicosia Cyprus W.P.C Officer Email: Department of Environment vmichael[at]environment.moa.gov.cy Estonia Ms. Mari-Liis KUPRI Tallinn Estonia Adviser Email: mari-liis.kupri[at]envir.ee Ministry of Environment Finland Ms. Marja RUOHONEN-LEHTO Helsinki Finland Senior Adviser Email: marja.ruohonen- Finnish Environment Institute lehto[at]ymparisto.fi France Mr. -

Agencies and Other Bodies 31/08/2021

EUROPEAN UNION EU WHOISWHO OFFICIAL DIRECTORY OF THE EUROPEAN UNION AGENCIES AND OTHER BODIES 14/09/2021 Managed by the Publications Office © European Union, 2021 FOP engine ver:20180220 - Content: Anninter export. Root entity 1, all languages. - X15splt1,v170601 - X15splt2,v161129 - Just set reference language to EN (version 20160818) - Removing redondancy and photo for xml for pdf(ver 20201206,execution:2021-09-14T18:36:02.373+02:00 ) - convert to any LV (version 20170103) - NAL countries.xml ver (if no ver it means problem): 20210616-0 - execution of xslt to fo code: 2021-09-14T18:36:15.478+02:00- linguistic version EN - NAL countries.xml ver (if no ver it means problem):20210616-0 rootentity=AGEN_OTH_SLASH_AGEN_OTH Note to the reader: The personal data in this directory are provided by the institutions, bodies and agencies of EU. The data are presented following the established order where there is one, otherwise by alphabetical order, barring errors or omissions. It is strictly forbidden to use these data for direct marketing purposes. If you detect any errors, please report them to: [email protected] Managed by the Publications Office © European Union, 2021 Reproduction is authorised. For any use or reproduction of individual photos, permission must be sought directly from the copyright holders. Agencies and other bodies Agencies 5 ACER — Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators 5 ENISA — European Union Network and Information Security Agency 5 FRA — European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights 5 GSA — European -

Section of Genetics (GEN)

Pixabay SECTION OF GENETICS (GEN) THE SECTION OF GENETICS (GEN) COMPRISES THE GENETIC EPIDEMIOLOGY GROUP Section head (GEP), THE GENETIC CANCER SUSCEPTIBILITY GROUP (GCS), AND THE BIOstATIstICS Dr Paul Brennan GROUP (BST). THE WORK OF THE SECTION COMBINES LARGE POPULATION-BASED stUDIES WITH LABORATORY AND BIOINFORMATICS EXPERTISE TO IDENTIFY SPECIFIC GENES AND GENETIC PROFILES THAT CONTRIBUTE TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF CANCER AND ELUCIDATE HOW THEY EXERT THEIR EFFECT ALONG WITH ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS. THE SECTION ALSO TRIES TO IDENTIFY INDIVIDUALS WHO ARE AT HIGH ENOUGH RISK THAT THEY ARE LIKELY TO BENEFIT FROM EXIstING RISK REDUCTION stRATEGIES. GEN’s projects usually involve extensive may have a larger effect than common fieldwork in collaboration with external single-nucleotide polymorphisms but investigators in order to develop large- that are not sufficiently frequent to scale epidemiological studies with be captured by current genome-wide appropriate clinical and exposure data, association genotyping arrays. GCS’s as well as biosample collection. This approach has been to use genomic and typically occurs within GEP, which bioinformatic techniques to complement has a primary interest in the analysis more traditional approaches for the study and identification of common genetic of rare genetic variants. GCS also uses susceptibility variants and their interaction genomics to explore how the variants with non-genetic risk factors. Genetic may be conferring genetic susceptibility analysis comprises either candidate to cancer. Thus, the research programme gene or genome-wide genotyping of GCS complements that of GEP, studies, as well as sequencing work. and also provides a facility for high- GEP studies also assess non-genetic throughput genomic techniques and the exposures, partly in recognition of the related bioinformatics to support GEN’s importance of non-genetic factors in large-scale molecular epidemiology driving cancer incidence, and also to projects and other IARC genomics facilitate accurate assessment of gene– projects. -

Les Responsables Des Jumelages Des Sections Nationales Du CCRE

COUNCIL OF EUROPEAN MUNICIPALITIES AND REGIONS CONSEIL DES COMMUNES ET REGIONS D’EUROPE 24.10.2011 Les responsables des jumelages du CCRE et de ses associations nationales Twinning Officers of CEMR and its national associations GROUPE DE TRAVAIL DU CCRE SUR LES JUMELAGES / CEMR WORKING GROUP ON TWINNING Président / Chairman : Mr Janusz MARSZAŁEK Maire d’Oświęcim (Pologne) / Mayor of Oświęcim (Poland) Secrétariat Général / Secretariat General Secrétaire Général / Secretary General : M. Frédéric VALLIER Directrice Citoyenneté et Coopération internationale / Director of Citizenship and International Cooperation : Mme Sandra CECIARINI Chargée de Projet Citoyenneté / Project Officer Citizenship : Mlle Manuella PORTIER 15 rue de Richelieu - 75001 PARIS (F) Tel.: 00 33-1-44 50 59 59 Fax: 00 33-1-44 50 59 60 E-mail: [email protected] ____________________ Albanie / Albania Belgique / Belgium Mr Fatos HODAJ Ms Betty DE WACHTER Director General Coordinator Albanian Association of Municipalities Association of Flemish Cities and Municipalities Rr Ismail Qemali, Pall Fratarit n° 27, Tirana Paviljoenstraat 7-9, 1030 BRUSSEL Tel.: 355-4-225 76 03 / Fax: 355-4-225 76 06 Tel +32.2.211 56 14 / Fax +32.2.211 56 00 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail : [email protected] Ms Isabelle COMPAGNIE Allemagne / Germany Chef de service - Europe – international Ms Elisabeth MANTEAU Ms Ines SPENGLER Secrétaire - Europe – international Coordinator Union des Villes et Communes de Wallonie (UVCW) Rat der Gemeinden und Regionen Europas / Deutsche Sektion Rue de l'Etoile, -

Velkommen Til

2015 TA’ med Hanstholm Rejser på ferie med oplevelser og hygge www.hanstholm-rejser.dk Velkommen til ... Velkommen i bussen Så er vi igen klar med et nyt katalog for sommeren 2015 med busrejser til hele Europa. Som noget nyt kan vi i år tilbyde kombinationsrejser med fly og bus, til to af Europas helt store metropoler; Paris og London. Som altid har vi rejseleder med hele vejen – også i flyet. Derudover tilbyder vi kør-selv på udvalgte desti- nationer, så kan du rejse når det passer dig. Vi kan tilbyde næsten 80 forskellige destinationer og håber dermed at du finder den rejse som passer lige netop til dig. Vi ser frem til at kunne byde dig velkommen. Vi vil gøre vort bedste til, du får en positiv og god ferieople- velse med hjem igen. Hos os følger bus, chauffør og rejseleder vore rejsegæster på hele rejsen, vi sætter service, kvalitet og tryghed i højsædet. Vi mener, det er vigtige forudsætninger for en tryg, god og spæn- dende rejse. Kig nærmere på de næste mange sider. Som altid er vi klar ved telefonen eller på mailen, hvis du skulle have spørgsmål. Tag et kig på vores hjemmeside – vi har netop lavet en ny. Her vil du kunne finde alle vores rejser og mere til. Nye rejser, tilbud, billeder og meget mere. Er du klar på nye oplevelser – vi er, og glæder os til det sammen med dig. På gensyn ! Chauffører & rejseledere, Susan & Michael Jeppesen Din ferie – vores arbejde, vi glæder os 2 Indholdsfortegnelse Bestil online 24 timer i døgnet – 7 dage om ugen Har du lyst til at sidde i ro og mag på det tidspunkt af døgnet, der passer dig bedst, kan du benytte dig af vort online booking- system. -

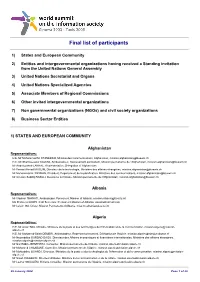

Final List of Participants

Final list of participants 1) States and European Community 2) Entities and intergovernmental organizations having received a Standing invitation from the United Nations General Assembly 3) United Nations Secretariat and Organs 4) United Nations Specialized Agencies 5) Associate Members of Regional Commissions 6) Other invited intergovernmental organizations 7) Non governmental organizations (NGOs) and civil society organizations 8) Business Sector Entities 1) STATES AND EUROPEAN COMMUNITY Afghanistan Representatives: H.E. Mr Mohammad M. STANEKZAI, Ministre des Communications, Afghanistan, [email protected] H.E. Mr Shamsuzzakir KAZEMI, Ambassadeur, Representant permanent, Mission permanente de l'Afghanistan, [email protected] Mr Abdelouaheb LAKHAL, Representative, Delegation of Afghanistan Mr Fawad Ahmad MUSLIM, Directeur de la technologie, Ministère des affaires étrangères, [email protected] Mr Mohammad H. PAYMAN, Président, Département de la planification, Ministère des communications, [email protected] Mr Ghulam Seddiq RASULI, Deuxième secrétaire, Mission permanente de l'Afghanistan, [email protected] Albania Representatives: Mr Vladimir THANATI, Ambassador, Permanent Mission of Albania, [email protected] Ms Pranvera GOXHI, First Secretary, Permanent Mission of Albania, [email protected] Mr Lulzim ISA, Driver, Mission Permanente d'Albanie, [email protected] Algeria Representatives: H.E. Mr Amar TOU, Ministre, Ministère de la poste et des technologies -

National Data Protection Authorities Austria Belgium

National Data Protection Authorities (updated on 19 April 2018) Austria Österreichische Datenschutzbehörde Wickenburggasse 8 1080 Wien Tel. +43 1 52152-0 e-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.dsb.gv.at/ Art 29 WP Member: Dr Andrea JELINEK, Director, Österreichische Datenschutzbehörde Belgium Commission de la protection de la vie privée Commissie voor de bescherming van de persoonlijke levenssfeer Rue de la Presse 35 / Drukpersstraat 35 1000 Bruxelles / 1000 Brussel Tel. +32 2 274 48 00 Fax +32 2 274 48 35 e-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.privacycommission.be/ Art 29 WP Vice-President: Willem DEBEUCKELAERE, President of the Belgian Privacycommission Bulgaria Commission for Personal Data Protection 2, Prof. Tsvetan Lazarov blvd. Sofia 1592 Tel. +359 2 915 3580 Fax +359 2 915 3525 e-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.cpdp.bg/ Art 29 WP Member: Mr Ventsislav KARADJOV, Chairman of the Commission for Personal Data Protection Curriculum Vitae (293 kB) Art 29 WP Alternate Member: Ms Mariya MATEVA Croatia Croatian Personal Data Protection Agency Martićeva 14 10000 Zagreb Tel. +385 1 4609 000 Fax +385 1 4609 099 e-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] Website: http://www.azop.hr/ Art 29 WP Member: Mr Anto RAJKOVAČA, Director of the Croatian Data Protection Agency Curriculum vitae (214 kB) Cyprus Commissioner for Personal Data Protection 1 Iasonos Street, 1082 Nicosia P.O. Box 23378, CY-1682 Nicosia Tel. +357 22 818 456 Fax +357 22 304 565 e-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.dataprotection.gov.cy/ Art 29 WP Member: Ms Irene LOIZIDOU NIKOLAIDOU Curriculum vitae (230 kB) Art 29 WP Alternate Member: Mr Constantinos GEORGIADES Czech Republic The Office for Personal Data Protection Urad pro ochranu osobnich udaju Pplk. -

Fahrplan & Preisliste Zur Verfügung Gestellt Von Sunnidays Fernflug

Fahrplan & Preisliste zur Verfügung gestellt von sunnidays fernflug & seetour e.K. Wir empfehlen für bessere Lesbarkeit, gegebenenfalls die jeweils interessanten Seiten oder alles auszudrucken. Als zusätzlichen Service bieten wir Ihnen Informationen wie Preislisten und Fahrpläne zum Überblick als PDF Dateien an, die Sie auf den folgenden Seiten finden. Sie können Ihre Buchung über unser Internetformular (< hier klicken) oder über das an dieser Datei hängende Faxformular an uns senden. Alles zu kompliziert? Sie können sich von uns auch ein Angebot erstellen lassen: über unser Anfrageformular (< hier klicken) Für den von Ihnen gewünschten Zeitraum sind noch keine Daten vorhanden ? Tragen Sie sich in unser Newslettersystem ein das nach Zielgebieten untergliedert ist. Sie werden automatisch informiert wenn es Neuigkeiten gibt und / oder ein Zeitraum zur Buchung freigegeben wird. Weitere Infos und Anmeldung auf unserer Webseite über http://www.newsletter.seetour24.de sunnidays fernflug & seetour e.K. — Tel/Fax: 0700 0700 2202 - Email: [email protected] www.seetour24.de www.stpeterline.de Willkommen an Bord! Einfach entspannt zu den in der Region vergleichbar. Sie bieten neben der Unterbringung in komfortablen Kabinen ein umfangreiches kulinarisches Angebot, Metropolen der Ostsee und sowie Unterhaltungs- und Wellness - Angebote. VISAFREI nach St. Petersburg! Von der 4-Bett Kabine, als günstigste Variante, über 2-Bett Innen- und Aussenkabinen bis hin zur luxuriösen Suite bieten die Schiffe Willkommen an Bord von St. Peter Line! Die Reederei St. Peter Line verschiedene Kategorien an Übernachtungsmöglichkeiten. Auch wurde 2009 gegründet. Nach dem großen Erfolg der Fährverbin- für das leibliche Wohl ist gesorgt: von einem Bistro für den kleinen dung zwischen Helsinki und St. Petersburg, wurde 2011 die zweite Hunger und der Sushi Bar, über das große Buffetrestaurant, bis Route als “Minicruise” Stockholm - Tallinn - St. -

JPO Alumni Association Directory

o o o UNDP Office of Human Resources, JPO Service Centre, Marmorvej 51, 2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark - www.jposc.undp.org The JPO Alumni Association (JAA) .............................................................................................................. 1 The Yearly JAA Member Directory ............................................................................................................. 1 JAA Overview ............................................................................................................................................. 4 JAA Members by Gender ....................................................................................................................... 4 JAA Members by Nationality .................................................................................................................. 4 JAA Members by JPO Agency ................................................................................................................. 6 JAA Members by last Year of JPO Assignment ....................................................................................... 7 JAA Members by post-JPO UN Status .................................................................................................... 8 JAA Members by current Sector of Activity ........................................................................................... 9 JAA Members by current Region of Residence .................................................................................... 10 JAA Alphabetical Directory...................................................................................................................... -

LIST of PARTICIPANTS Officielle Sans

MED-24-5 FINAL 29 April 2013 Council of Europe Standing Conference of Ministers of Education “Governance and Quality Education” 24 th session Helsinki, Finland, 26-27 April 2013 Conférence permanente du Conseil de l’Europe des Ministres de l'Education « Gouvernance et Education de qualité » 24 e session Helsinki, Finlande, 26-27 avril 2013 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS LISTE DES PARTICIPANTS PARTIES TO THE EUROPEAN CULTURAL CONVENTION / PARTIES A LA CONVENTION CULTURELLE Ms Margot ALEIX MATA EUROPEENNE Deputy to the Permanent Representative PERMANENT REPRESENTATION OF ALBANIA / ALBANIE ANDORRA TO THE COUNCIL OF EUROPE 10, av. du Président Robert Schuman Head of Delegation 67000 STRASBOURG, FRANCE Mr Myqerem TAFAJ Working Language: English/French Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Education and Science ARMENIA / ARMÉNIE MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE Rruga e Durresit, No. 23 Head of Delegation Mr Armen ASHOTYAN 1001 TIRANA, ALBANIA Working Language: English Minister of Education and Sciences MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE Mr Tidita ABDURRAHMANI Main Avenue, Government House 3 General Director 0010 YEREVAN, ARMENIA INSTITUE OF EDUCATIONAL DEVELOPMENT Working Language: English Mr Ermal ELEZI Mr Robert SOUKIASSYAN Director, Department for Policies and Head of the Higher and Post-Graduate International Programmes Education Department MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE Rruga e Durresit, No. 23 Main Avenue, Government House 3 1001 TIRANA, ALBANIA 0010 YEREVAN, ARMENIA Working Language: English Working Language: English ANDORRA / ANDORRE Mr Arshaluys TARVERDYAN Rector of State Agrarian University Head of Delegation ARMENIAN NATIONAL AGRARIAN Ms Roser SUÑÉ UNIVERSITY Minister of Education and Youth 74 Teryan Street MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND YOUTH 0009 YEREVAN, ARMENIA Av.