A Postscript to the Meredith Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Texas Observer APRIL 17, 1964

The Texas Observer APRIL 17, 1964 A Journal of Free Voices A Window to The South 25c A Photograph Sen. Ralph Yarborough • • •RuBy ss eII lee we can be sure. Let us therefore recall, as we enter this crucial fortnight, what we iciaJ gen. Jhere know about Ralph Yarborough. We know that he is a good man. Get to work for Ralph Yarborough! That is disputed, for some voters will choose to We know that he is courageous. He has is the unmistakable meaning of the front believe the original report. not done everything liberals wanted him to page of the Dallas Morning News last Sun- Furthermore, we know, from listening to as quickly as we'd hoped, but in the terms day. The reactionary power structure is Gordon McLendon, that he is the low- of today's issues and the realities in Texas, out to get Sen. Yarborough, and they will, downest political fighter in Texas politics he has been as courageous a defender of unless the good and honest loyal Demo- since Allan Shivers. Who but an unscrupu- the best American values and the rights of crats of Texas who have known him for lous politician would call such a fine public every person of every color as Sam Hous- the good and honest man he is lo these servant as Yarborough, in a passage bear- ton was; he has earned a secure place in many years get to work now and stay at it ing on the assassination and its aftermath, Texas history alongside Houston, Reagan, until 7 p.m. -

Edwin Walker, Controversial General, Dies at 83

THE _N$W YORK TIMES OBITUARIES 'TUESDAY. NOVEMBER 2, 199.1 Edwin Walker, Controversial General, Dies at 83 By ERIC PACE The general was relieved of his com- A vociferous mand while the Inquiry was conducted.. Mal. Gen. Edwin A. Walker, whose In June Nal. the Army said the right-wing political activities led 10 an investigation showed that the general's; official rebuke and his resignation anti-Communist Information program was "not Mirth- from the Army in 1981, died Ulf Sunday utuble to any program of the John, at his home in Dallas. lie was 83 who was a target Birch Society." But it admonished the The cause was lung disease, the Dal- general "far taking injudicious =lanai las County medical examiner's office of Oswald. and for making derogatory public! sold in a report yesterday. statements about prominent Ainerl-' General Walker, a lanky, much-deco- cans." rated Texan who led combat units In evidence of Mr. Oswald's capacity for He resigned on Non. 2, 1961, contend.' World War 11 and the Korean War, violence. big that he "must be free from the ended his 30-year Army career be- puwer of little men who, hr the name of cause, he said, he "could no longer The Issue that led to Geueral Walk- er's resignation begun In April 1961 my country, punish loyal service to It," serve In uniform and be a collabore tar when Overseas Weekly, a privately By resigning rather than retiring, he with the release of United States saver. passed up retirement pay that at the manly to the United Notions" owned newspaper circulated among members of the armed forces over- time would have amounted to $12000 a On April 10, 1863, a aniper fired at seas, accused the general at using an year. -

Group Research, Inc. Records, 1955-1996 MS# 0525 ©2007 Columbia University Library

Group Research, Inc. Records, 1955-1996 MS# 0525 ©2007 Columbia University Library This document is converted from a legacy finding aid. We provide this Internet-accessible document in the hope that users interested in this collection will find this information useful. At some point in the future, should time and funds permit, this finding aid may be updated. SUMMARY INFORMATION Creator Group Research, Inc. Title and dates Group Research, Inc. Records, 1955-1996 Abstract Founded by Wesley McCune and based in Washington DC until ceasing operations in the mid-1990s, Group Research Inc. collected materials that focus on the right-wing and span four decades. The collection contains correspondence, memos, reports, card files, audio-visual material, printed matter, clippings, etc. Size 215 linear ft. (512 document boxes; Map Case 14/16/05 and flat box #727) Call number MS# 0525 Location Columbia University Butler Library, 6th Floor Rare Book and Manuscript Library 535 West 114th Street Page 1 of 142 Group Research Records Box New York, NY 10027 Language(s) of material English History of Group Research, Inc. A successful journalist for such magazines as Newsweek, Time, Life and Changing Times as well as a staff member of several government agencies and government-related organizations, Wesley McCune founded Group Research Inc. in 1962. Based in Washington DC until ceasing operations in the mid-1990s Group Research Inc. collected materials that focus on the right--wing and span four decades. The resulting Group Research archive includes information about and by right-wing organizations and activists in the form of publications correspondence pamphlets reports newspaper Congressional Record and magazine clippings and other ephemera. -

Warden: Prison Life and Death from the Inside out (Review) Mitchel P

Warden: Prison Life and Death from the Inside Out (review) Mitchel P. Roth Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Volume 110, Number 1, July 2006, pp. 156-157 (Review) Published by Texas State Historical Association DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/swh.2006.0029 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/203061 [ This content has been declared free to read by the pubisher during the COVID-19 pandemic. ] 156 Southwestern Historical Quarterly July George Phenix remembers the volatile political climate of Dallas. On assign- ment one week before Kennedy’s shooting while covering Alabama Gov. George Wallace’s speech before approximately two thousand right-wingers at Dallas’s Baker Hotel, Phenix was physically assaulted and twice thrown to the ground by the ultraconservative Gen. Edwin Walker. The conservative crowd robustly applauded Walker’s efforts; no one yet knew that one month earlier Lee Harvey Oswald had attempted to assassinate Walker in his Dallas home. Bill Mercer writes about the chaotic conditions at police headquarters after the capture of Lee Harvey Oswald, focusing on the impromptu midnight press conference with Oswald. Mercer acknowledges that among those in attendance at the press conference was Jack Ruby, who apparently had no trouble entering police headquarters, given the confused state of affairs. Mercer also covered the arrival at police headquarters of Oswald’s wife, Marina, and his mother, Marguer- ite, who steadfastly proclaimed her son’s innocence. Wes Wise focuses on the political instability of Dallas, recounting the Octo- ber 1963 visit of former Senator and U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Adlai Stevenson, who was accosted by several conservative, anti-U.N. -

PHOTOGRAPHS EDWIN WALKER Le1—.1 EDWIN A. Walhr FILE (DALLAS P.D

PHOTOGRAPHS EDWIN WALKER Le1—.1 EDWIN A. WALhR FILE (DALLAS P.D. DEPT.) a-VeaCe:11-m-rf./5i- :,/ Jas sary 511 1964 4py- JUN2 0 Co ______ 19OS I Mr. J. R. Curry 1.hief of Police Subjects General '.(iwiet A. wellsor turGlazy by firc=1:19 Offence !ir Sirs On April 11, 1963, I wen imatruetz4 by Captain O. A. Jong* to cake an icvoaticatica ea the above effsnac. 1 Thie oniony ecatnoted Cameral Walter at his hose at 4011 ?u. 10 GrecO Blvd on April 12, 1963. In the oat co of this invertigntioe I have porCmelly interviewed GcsArml Welkor at his botze at letat five tic e. I huge toad t=erons telephone con- Iv-mations with Cvnerml walkor recnrdirj VAG in- veeLication. The lent tine I had te1c2t!ene eon- tact with Cones:n.1 Valkor vae on the evanitzs of December 20, 1963, at which time ha had received a long dipt=noo 4=11 throntonin5 hie life. At the present tics *hie offence ie still boing investisatod. I have receivod no inetrnotiona to close this case. This once will =mein motive until it onn be ehJen whs we responsible ror thisLoffamoe. Respectfully, tg.:Cm Lt. •f Police Per-gory Bureau 1.T.ELComa . 4 0 f4 41 ' • t December 31, 1963 O Hr. J. r. Curry Chief of Police Subject! General &twin A. Talker Burglary by Firearms Offense f F 48156 Pursuant to your inetructiona of December 24, 1963, a complete file of the investigation of Offense 0 F 48156 has bean compiled. -

10/28/61 Juggernaut: the Warfare State, in the Nation, P. 328, Fred J

Walker 10/28/61 Juggernaut: The Warfare State, in The Nation, p. 328, Fred J. Cook 11/18-24/63 General Walker says he had a speaking engagement in Hattiesburg, MS, 11/18 or 11/19/63; went from there to New Orleans and stayed two or three days; was travelling by air between New Orleans and Shreveport when, about half-way, pilot announced that Kennedy had been assassinated. Stayed in Shreveport two nights [11/22, 23] before returning to Dallas. Was in New Orleans between 11/19-20 and 11/22/63 Testimony, General Edwin A. Walker, taken by Wesley Liebeler, Dallas, 7/23/64. Warren Report, Hearings XI, p. 426. 12/1/63 On a statewide basis, the most recent test of ultraconservative strength was the 1962 Governor's race. Edwin A. Walker, the former major general relieved of his command after the army accused him of indoctrinating troops with John Birch Society ideas, ran a poor sixth in a field of six. AP, Jules Loh, Texas and its conscience 12/2/63 Dallas - Former Major General Edwin A. Walker said today the assassination of President Kennedy "had very, very serious implications, worldwide." "God has given a warning which no man alive can ignore," Walker told a news conference. "The doors of our country are wide open to foreign penetration." AP 12/2/63 Garden City, N.Y. - A 12/9 address by Major General Edwin A. Walker on Long Island has been canceled. L.W. Osterstock, general manager of the Garden City Hotel, said there had been many telephoned protests of the scheduled appearance and some callers voiced threats. -

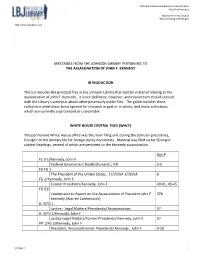

Materials from the Johnson Library Pertaining to the Assassination of John F

National Archives and Records Administration http://archives.gov National Archives Catalog https://catalog.archives.gov http://www.lbjlibrary.org MATERIALS FROM THE JOHNSON LIBRARY PERTAINING TO THE ASSASSINATION OF JOHN F. KENNEDY INTRODUCTION This list includes the principal files in the Johnson Library that contain material relating to the assassination of John F. Kennedy. It is not definitive, however, and researchers should consult with the Library's archivists about other potentially useful files. The guide includes those collections which have been opened for research in part or in whole, and those collections which are currently unprocessed or unavailable. WHITE HOUSE CENTRAL FILES (WHCF) This permanent White House office was the main filing unit during the Johnson presidency, though not the primary file for foreign policy documents. Material was filed under 60 major subject headings, several of which are pertinent to the Kennedy assassination. Box # FE 3-1/Kennedy, John F. Federal Government Deaths/Funerals, JFK 3-5 EX FG 1 The President of the United States, 11/22/64-1/10/64 9 FG 2/Kennedy, John F. Former Presidents/Kennedy, John F. 40-41, 43-45 FG 635 Commission to Report on the Assassination of President John F. 376 Kennedy (Warren Commission) JL 3/FG 1 Justice - Legal Matters/Presidential Assassinations 37 JL 3/FG 2/Kennedy, John F. Justice Legal Matters/Former Presidents/ Kennedy, John F. 37 PP 1/FG 2/Kennedy, John F. President, Personal/Former Presidents/ Kennedy, John F. 9-10 02/28/17 1 National Archives and Records Administration http://archives.gov National Archives Catalog https://catalog.archives.gov http://www.lbjlibrary.org (Cross references and letters from the general public regarding the assassination.) PR 4-1 Public Relations - Support after the Death of John F. -

One Hundred Third Congress of the United States of America

S. J. Res. 129 One Hundred Third Congress of the United States of America AT THE FIRST SESSION Begun and held at the City of Washington on Tuesday, the fifth day of January, one thousand nine hundred and ninety-three Joint Resolution To authorize the placement of a memorial cairn in Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, Virginia, to honor the 270 victims of the terrorist bombing of Pan Am Flight 103. Whereas Pan Am Flight 103 was destroyed by a bomb during the flight over Lockerbie, Scotland, on December 21, 1988; Whereas 270 persons from 21 countries were killed in this terrorist bombing; Whereas 189 of those killed were citizens of the United States including the following citizens from 21 States, the District of Columbia, and United States citizens living abroad: ARKANSAS: Frederick Sanford Phillips; CALIFORNIA: Jerry Don Avritt, Surinder Mohan Bhatia, Stacie Denise Franklin, Matthew Kevin Gannon, Paul Isaac Garrett, Barry Joseph Valentino, Jonathan White; COLORADO: Steven Lee Butler; CONNECTICUT: Scott Marsh Cory, Patricia Mary Coyle, Shannon Davis, Turhan Ergin, Thomas Britton Schultz, Amy Elizabeth Shapiro; DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA: Nicholas Andreas Vrenios; FLORIDA: John Binning Cummock; ILLINOIS: Janina Jozefa Waido; KANSAS: Lloyd David Ludlow; MARYLAND: Michael Stuart Bernstein, Jay Joseph Kingham, Karen Elizabeth Noonan, Anne Lindsey Otenasek, Anita Lynn Reeves, Louise Ann Rogers, George Watterson Wil- liams, Miriam Luby Wolfe; MASSACHUSETTS: Julian MacBain Benello, Nicole Elise Bou- langer, Nicholas Bright, Gary Leonard Colasanti, -

1963 John F. Kennedy Assassinated

Reading 1963 John F. Kennedy assassinated John Fitzgerald Kennedy, the 35th president of the United States, is assassinated while travelling through Dallas, Texas, in an open-top convertible. First lady Jacqueline Kennedy rarely accompanied her husband on political outings, but she was beside him, along with Texas Governor John Connally and his wife, for a 10- mile motorcade through the streets of downtown Dallas on November 22. Sitting in a Lincoln convertible, the Kennedys and Connallys waved at the large and enthusiastic crowds gathered along the parade route. As their vehicle passed the Texas School Book Depository Building at 12:30 p.m., Lee Harvey Oswald allegedly fired three shots from the sixth floor, fatally wounding President Kennedy and seriously injuring Governor Connally. Kennedy was pronounced dead 30 minutes later at Dallas’ Parkland Hospital. He was 46. Vice President Lyndon Johnson, who was three cars behind President Kennedy in the motorcade, was sworn in as the 36th president of the United States at 2:39 p.m. He took the presidential oath of office aboard Air Force One as it sat on the runway at Dallas Love Field airport. The swearing in was witnessed by some 30 people, including Jacqueline Kennedy, who was still wearing clothes stained with her husband’s blood. Seven minutes later, the presidential jet took off for Washington. The next day, November 23, President Johnson issued his first proclamation, declaring November 25 to be a day of national mourning for the slain president. On that Monday, hundreds of thousands of people lined the streets of Washington to watch a horse- drawn caisson bear Kennedy’s body from the Capitol Rotunda to St. -

The Rabbit Hole”

NOTE: This script has been coded for identification purposes. 11/22/63 101/102 - “The Rabbit Hole” Written by Bridget Carpenter Directed by This episode takes place during June, 2015 and October 21-28, 1960 Network Draft B – 1/29/15 ©2015 Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. This script is the property of Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. No portion of this script may be performed, reproduced or used by any means, or disclosed to, quoted or published in any medium without the prior written consent of Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. ACT ONE IN BLACKNESS: We hear a man’s voice, reading an essay aloud. JAKE (V.O.) The day that changed my life. The day that changed my life wasn’t a day, but a night. It was Halloween night. INT. HOUSE - LIVING ROOM - NIGHT - FLASHBACK - 1960 CRASH. A door smashes open into a modest living room. JAKE (V.O.) It was the night my father murdirt my mom and my brothers and my sister with a hammer. The following images are fragmentary, whip-pan blurs, terrifying, nightmarish, adrenaline-inducing. INT. HOUSE - HALLWAY - NIGHT - FLASHBACK - 1960 Three SMALL CHILDREN in Halloween costumes -- FAIRY, COWBOY, GHOST -- run screaming down a hallway. WOMAN (O.S.) No! No! Nooo! INT. HOUSE - BEDROOM - NIGHT - FLASHBACK - 1960 A woman’s arm pushes away a swinging hammer. JAKE (V.O.) My father was real mean when he drank. INT. HOUSE - BEDROOM - NIGHT - FLASHBACK - 1960 Torn fragments and pieces of Halloween costumes lay scattered across the floor -- cowboy hat, mask, fairy wings -- in a pool of blood. Blood is spattered on the floral wallpaper. -

NORSTAD, LAURIS: Papers, 1930-87

DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY ABILENE, KANSAS NORSTAD, LAURIS: Papers, 1930-87 Accession A94-5 Processed by: DJH Date Completed: July 1992 On June 15, 1986, General Lauris Norstad agreed to donate his personal papers to the Eisenhower Library. The Library received the papers in several shipments between 1986 and 1989. Linear feet of shelf space: 62 Approximate number of pages: 116,800 Approximate number of items: 60,000 An instrument of gift for these papers was signed by Mrs. Isabel Norstad in November 1993. Literary rights in the unpublished writings of General Norstad in this collection and in all other collections of papers received by the United States have been donated to the public. Under terms of the instrument of gift the following classes of documents are withheld from research use: 1. Papers which constitute an invasion of personal privacy or a libel of a living person. 2. Papers which are required to be keep secret in the interest of national defense or foreign policy and are properly classified. SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE The Papers of General Lauris Norstad, United States Air Force officer, cover the period 1930 to 1987, with the bulk of the materials falling into the years 1942-1962. Norstad held various staff positions overseas and in Washington D.C. during and after World War II before serving in several European commands leading to his appointment as Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR) in 1956. A small segment of these papers are dated 1969-1974 when Norstad served as a member of the President’s Commission on an All-Volunteer Armed Force and as a member of the General Advisory Committee on Arms Control and Disarmament. -

I Have Completed My Review of the FBI HQ Edwin A. Walker File, FBI

I have completed my review of the FBI HQ Edwin A. Walker file, FBI number 163-11998, section one, that the FBI produced in response to our request for additional information. There was only one section and only one serial number. The information was not found to be an assassination record. File 4.16.4 (FBI-34) Fagnant e:\wp-docs\fbi\summary\fbi34.fol I have completed my review of the one and only section of FBI HQ Edwin Walker file, FBI number 44-34673, serials 1-3, that the FBI produced in response to our request for additional information. I determined that the records contained in this Edwin Walker file did not relate to the General Edwin A. Walker with whom we are concerned. I did not find any assassination records in this file. File 4.16.4 (FBI-34) Fagnant e:\wp-docs\fbi\summary\fbi34.fol I have completed my review of two sections of the FBI HQ General Edwin A. Walker file, FBI number 116-165494, serials 1-75, Section 1 1/30/50 through 3/12/64; serial scope 1-75 • 116-165494-(51, 52, 54-57, 59) All seven serial numbers are duplicate documents. The originals are filed in 62-109060. These documents relate the Dallas Police Department’s investigation into LHO’s alleged attempt to assassinate General Walker, Marina’s testimony in this regard, and the possibility of the same rifle being used in the assassination attempt on Walker and the assassination of JFK. • 116-165494-(53, 1st NR after 54, 1st NR after 56, 60, 1st NR after 60, 61, 62, 1st NR after 62, 63, 1st NR after 63, 2nd NR after 63, 64, 1st NR after 64, 2nd NR after 64, 65, 66, 71-74, 1st NR after 74, 2nd NR after 74, 75) All 23 serial numbers are duplicate documents.